In response to:

"The Formidable Dr. Robinson": A Reply from the January 20, 1966 issue

To the Editors:

May I offer some data relevant to Dr. Hannah Arendt’s Reply to the Jewish Establishment which appeared in your issue of January 20th?

Dr. Arendt quotes the old Jewish precept that it ought to be preferred to be killed oneself to delivering another Jew to the Gentiles to be killed. Indeed, it is fundamental to the whole Jewish Weltanschauung that no life is more valuable than any other. In the words of the Talmud: “What makes you think your blood is redder? Perhaps his blood is redder.” (Pesanhim 25b.)

To question the behavior of the rabbinate in Europe, in this context, is more than justified. Those who are interested in a case-study how these lofty precepts were interpreted and applied in practice will be rewarded if they consult a book entitled “Pinkas Bendin,” published in Israel some years ago both in Hebrew and Yiddish. They will find there records of actual discussions, conducted in the ghetto of Bendin, in which these precepts were invoked only to be promptly abandoned.

Dr. Arendt writes: “It seems there was not one Rabbi who did what Dompropst Bernhard Lichtenberg, a Catholic priest, or Propst Heinrich Grüber, a Protestant minister, had tried to do—to volunteer for deportation.” Rabbis, of course, were not given a choice, like the two Christian ministers of religion mentioned, to be deported or not to be deported. They were deported without options.

There existed, however, in Hungary a rather special situation. Quite a few Rabbis in Hungary had just this kind of choice. Dr. Rudolf Kasztner’s project, the special train of rescue, aimed at selecting and rescuing the prominent Jews in Hungary. Officially, the train’s destination was Palestine and thus prominent Zionists had, in theory if not in practice, a claim to priority. In fact, “prominents” of all kind were included, depending on considerations which are impossible to evaluate at this stage. Thus, in places where this was not yet late, the Rabbi or Rabbis of the locality were offered seats for themselves and their families on the special train, before the deportation of the local ghetto.

To the best of my knowledge, no Rabbi, including those who right up to that day preached that emigration to Palestine was a sin, refused to be taken out of the panic-stricken ghettoes. With one and only one exception. Dr. Emil Roth, Chief Rabbi of the progressive (neologue) synagogue in the city of Gyoer (Raab), refused to abandon his congregation at that time of ultimate distress. He declined the seat offered to him on the special train. He was regarded as not only the most sincere and dedicated but also as the most able Rabbi of his generation. He was a leading Zionist and still a relatively young man, in his early forties, who could easily have justified to himself his escape by the future services he might have been able to render. He chose instead to serve in the only way which he could accept as being in harmony with the moral teachings of his religion. Dr. Roth did not return.

Gershon Weiler

Canberra, Australia

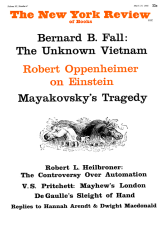

This Issue

March 17, 1966