The life of John James Audubon was full of ambiguities, contradictions, frustrations, alienations. With such attributes, his biography could easily meet the fashionable specifications of our own period. But he was also a man of heroic mold, and heroes for the moment are not fashionable. What is worse for his present fame, he was, within his strict avian limits, a skilled draughtsman, indeed a consummate artist; and that is a severe disqualification in an age populated by solemn popcorny jokesters who transfer nothingness to a canvas and sell it as art, or who crown such vacuous achievements by erasing nothingness and coyly signing their names to that double nonentity.

In order to characterize either the new edition of Audubon’s Birds of America or the latest biography I find it necessary to outline Audubon’s life, for I have fallen in love with the man and his work all over again, as Melville fell in love with Hawthorne’s enchanting mind. The most charitable thing one can say about Mr. Alexander Adams’s biography is that he found Audubon’s character so disenchanting and his whole career so distasteful, that only the most severe moral discipline could have kept him at his self-imposed task. In retelling Audubon’s story I shall do justice to both Audubon and his new biographer; for I shall show that each is—in quite contrasting ways—strictly for the birds.

Jean Jacques Fougère Rabin Audubon, also nicknamed La Forêt, was born it now seems clear in 1785. But every attempt to unravel the mystery of his parentage only makes a greater mystery of equally valid documents and reported events, including some of Audubon’s own letters to his wife. His childhood memories, curiously, did not go back farther than when he was eight, as a boy in Nantes, supposedly brought to France at four by his sea-going merchant father, Jean Audubon. Whether Audubon’s early memories were erased by shock or deliberately suppressed or confusedly interwoven with an improbable past, which he was bound under oath to his father to conceal, we shall never know. Supposing he was indeed, as rumor long hinted, the lost Dauphin of France, whisked out of prison during the revolution in 1793, certain princely traits in Audubon’s character would be easier to explain. If on the other hand, Audubon was actually the illegitimate son of the sea-captain and a Santo Domingan Creole woman, this would hardly account for his uncertainty about dates and birthplaces and his sometimes imperfect sense of reality. But if his life was actually based on a fiction, that might well be responsible for his free and loose way of dealing with other parts of it, as it were a fictitious incident in the same improbable fairy story of a stolen prince condemned to obscurity.

At all events the verifiable story of Audubon’s life begins only at the late age of eleven. From then on it can be followed with confidence till he died, old before his time, his mind crumbling away during the last four years, in 1851.

FROM THE OUTSET, Audubon bore the unmistakable brand of his own genius for even as a child he was a passionate lover of birds, and soon became an indefatigable egg-snatcher, hunter, collector, and limner of birds. Behind that impulse was a traumatic incident in his childhood, which he recognized as having an influence on his later life. He had witnessed a pet monkey cold-bloodedly attack and kill a favorite talking parrot, himself agonized because his outraged screams did not move a servant to intervene. Though his own love for birds did not prevent him from killing them for closer observation or for food, even as the equally humane Alfred Russel Wallace did later, one may interpret his pictures, in the light of this early event, as so many zealous efforts to restore dead birds to life. That desire dominated his existence, and as far as art may ever truly preserve life, he marvelously succeeded.

Handsome, headstrong, volatile, foolhardy, as bored with book learning as was young Darwin, Audubon was cut out for life on the American frontier. This, as much as his father’s wish to save him from becoming a Napoleonic conscript, perhaps led his watchful parent to ship the lad at eighteen off to the New World, to look after Mill Grove, a farm with a lead mine he had acquired in Pennsylvania. Audubon, brought up luxuriously by a doting stepmother, ever ready to spoil him, arrived in the United States in 1803, full of highfallutin airs and pretensions. He later laughed at himself for having gone hunting in silk stockings and the finest ruffled shirt he could buy in Philadelphia. He played the flute and the violin, was a daring skater, a famous dancer, an expert fencer, and a crack shot with the rifle. In short, the perfect old-style aristocrat, proud, hot-tempered, careless of danger, and even more gaily careless of money—the precise opposite of the canny, methodical, money-making philistine that his new biographer tirelessly reproaches him for not being.

Advertisement

With this heady combination of qualities, Audubon might easily have been slain in a duel or have turned into a good-for-nothing Don Juan, frittering away his life in aimless erotic adventures. But he was saved by his two lifelong loves: his love of birds and his love of Lucy Bakewell, a girl on a neighboring estate, Fatland Ford, whom he courted in a cave, where they watched the peewees that fascinated him. At the end of five years, the reserved girl and the exuberant French coxcomb married and started their lives afresh as pioneers in the newly settled land beyond the Alleghenies. Almost overnight, Audubon changed his silks for leather hunting clothes and let his hair grow down to his shoulders: and in the course of his life, he gradually turned into an archetypal American, who astonishingly combined in equal measure the virtues of George Washington, Daniel Boone, and Benjamin Franklin.

In the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, from Cincinnati and Louisville to New Orleans, Audubon found a mode of life that fulfilled his deepest need, as deep as his love for Lucy: direct contact with nature in every aspect and above all with the teeming animal and bird life of river, swamp, and woodland, at a time when the passenger pigeons periodically blackened the skies, and many species of bird, now extinct, were still thriving. Years later, in recollection. Audubon still thrilled over this life, though he had encountered his share of the frontier’s rapscallions, bullies, thieves, and cutthroats. “I shot, I drew, I looked on nature only; my days were happy beyond human conception…. The simplicity and whole-heartedness of those days I cannot describe: man was man, and each, one to another, a brother.” So he remembered that early period; and even at the end of his career he sought to recover the wild gamey taste of this frontier existence in his last Missouri River expedition. He shared, too, the pioneer’s love for tall stories, wild humor, practical jokes; and sometimes, as in the gulling of the visiting naturalist, Raffinesque, with drawings of wild creatures that existed only in his fantasy, he got himself into hot water as a reliable naturalist by forgetting how these backwoods jokes might look in print.

ONLY ONE PART of this existence was repulsive to Audubon, though his obligations as a family man made him go erratically through the motions: the necessity of making a living by trade. His career as a business man was a most extravagant practical joke that he played on himself: a predestined but and victim through his own impulsive, generous nature. His own words tell everything. “Merchants crowded to Louisville…None of them were, as I was, intent on the study of birds, but all were deeply impressed by the value of dollars. I could not bear to give the attention required by my business.” On more than one journey, he confessed, he would thoughtlessly leave his horses unguarded, though laden with goods and dollars, to watch the motions of a warbler.

While Audubon’s knowledge of birds became steadily richer, his business ventures, culminating in a crazy investment in a steam mill, made him poorer. Finally, in 1819, a time of general economic crisis, everything went to smash. He was jailed for debt and was declared bankrupt. Audubon always blamed his own bad judgment for what happened; but the misery of finding himself down and out was intensified by the deaths of his two sickly little daughters; and he had to start life again from scratch, at thirty-four, with only his clothes, his drawing outfit, and his gun. But from that low point on, though one would hardly guess it from Mr. Adams’s biography, the curve of his life went upward for the next quarter of a century.

Until Audubon made the decision that launched his four-volume work on The Birds of America, he and his Lucy went through half-a-dozen grim years that might have broken and permanently embittered a less stable couple. Driven to turn his attention partly from birds to human faces, in order to make a living as a limner of quick portraits, Audubon lived a penurious, vagrant life, as drawing teacher, dancing master, taxidermist. Meanwhile Lucy was left to fend largely for herself, as governess and teacher, while rearing their two sons, Victor and John Woodhouse. These were bitter years for both Audubon and his wife: years of recurrent poverty, frequent separation, partial alienation, blank despair. Even after Audubon’s fortunes began to mend, Lucy seems to have distrusted his buoyant faith in their future, and to have openly doubted his ability to support his family and make their marriage again become a reality. But, determined both to establish his work and salvage his marriage, Audubon drew from his love for his wife and his sons the strength he needed to overcome his recurrent depressions and to go on. The phrenologists who described Audubon as a strong and constant lover and an affectionate father guessed right about his nature.

Advertisement

None of Audubon’s biographers is able to give a full account of this marriage: Who for that matter has ever given an even half-way full account of any marriage? But enough letters have been preserved, in addition to some of Audubon’s journals, to indicate that this couple furnish a classic example of the opposed temperamental types that Freud first defined as oral and anal: let us call them, on a less infantile level, the spenders and the hoarders. Lucy, her letters show, was a downright, matter-of-fact soul; and from the meager evidence that remains one suspects that there must have been reservations, tensions, dissatisfactions almost from the beginning; for Lucy, brought up in comfort, could not share the hunter’s unfettered outdoor pleasures, and worse, she did not have any birds to fall back on.

Lucy, in her tight, watchful, realistic, “practical,” anxious way was the kind of woman who so often, once the first glamor of sexual intimacy has faded, leads a man to seek the carefree sympathy or the more relaxed erotic play of another woman. Fortunately, as far as negative evidence may indicate, Audubon’s mistresses were all birds; and whatever Lucy’s doubts and inhibitions, he never lost faith in their common destiny. “If I were jealous,” Lucy once remarked. “I should have a bitter time of it, for every bird is my rival.” Not that this dashing, warmhearted man was ever insensitive to the charms of women, whether they were his seventeen-year-old pupil, Eliza Pirrie, or the unidentifiable New Orleans woman who raised an erotic storm in his bosom by commissioning him to do a portrait of her, naked, or even a neat plump serving maid, “tripping as briskly as a killdeer.”

YET THIS WAS A TRUE MARRIAGE, as well as an enduring one; and if Lucy’s sufferings had fewer immediate compensations, both in the end gained, for the achievement of Audubon’s great work was possible only because he had in the throes of the crisis that separated them absorbed Lucy’s virtues and made them his own. He never lost his impulsive generosity or his contempt for mere money; but in the last third of his life these traits were counter-balanced by a strict attention to irksome financial details, an unwavering fidelity to his dominant purpose, and a capacity to drive himself, day after day, at his work, often drawing from fourteen to seventeen hours at a stretch or endlessly tramping the streets of Manchester or London to find subscribers for his folios. Perhaps the best proof of his inner transformation is that, once he was committed to the publication of The Birds of America, he resolutely turned his back on the life he loved most, as hunter, naturalist, explorer, bird-watcher, and bird-listener, and lived in exile, to carry through the project. To ensure the great success that soon came to him, he endured the oppressions and discomforts of formal civilized life in London and Paris, overcoming his shyness, his terror of polite society, his healthy puritanic distaste for tobacco and spirits and refined food. In the course of this effort the booney backwoodsman became a great man of the world, at home among princes and presidents, accepted as an equal by artists and scientists, able to endure stuffy dinners and even duller lectures in the many scientific societies that enrolled him as a member.

Such an inner transformation after a severe crisis, sexual or religious, has been described at length by William James. It needed Audubon’s complete failure in business for him to discover what now must seem to everyone—except his latest biographer—perfectly obvious: that the only life possible for him was that of a naturalist and a painter of the wild creatures he loved and studied so intensely. That obsession proved his salvation. Once he had accepted as a conscious vocation what had hitherto blindly absorbed him in practice, he was ready not only to enjoy it but to transpose the results to the realm of mind. In that task, he proved himself a master of every relevant detail, and within less than four years succeeded in rehabilitating his marriage, while establishing himself as a unique source of firsthand knowledge about the lives and habitats of American birds: over four hundred species, many painted and described for the first time.

BEFORE APPRAISING Audubon’s central achievement, The Birds of America, let me pay my disrespects to Mr. Adams’s new biography, whose constant derogation and denigration of Audubon called forth this preliminary excursion into Audubon’s character and career. This new book, with a painstaking and even examplary attention to recorded facts, goes over the same general ground as that covered by Francis Hobart Herick (1917), Constance Rourke (1936), and Alice Ford (1964). On the surface, Mr. Adams, to judge by information provided by his publisher, would seem to have special qualifications for appreciating Audubon’s work and influence; for he is a professional conservationist, a trustee of the National Conservancy, a Vice President of a local Audubon Society. But all these helpful interests seem to have been nullified by a temperamental aversion to Audubon himself, which causes him to present Audubon’s character in the most unfavorable light possible, and to turn his great career into a series of dismal and depressing failures.

Mr. Adams has skillfully marshalled the known facts about Audubon’s life as if with a single purpose in view: to support his conviction that if Audubon had only during the early years of his marriage paid sufficient attention to business, instead of perpetually playing truant, hunting, bird-watching, making his laborious drawings, The Birds of America need never have been painted or published. That is a highly original judgment, indeed a breathtaking one, but Audubon himself was in full accord with it. “We had marked Louisville,” he noted in 1835 in the Memoir he wrote for his family, “as a spot designed by nature to be a place of great importance, and, had we been as wise as we now are, I might never have published The Birds of America, for a few hundred dollars, laid out at that period in lands or town lots would, if left to grow over with grass to a date ten years past, have become an immense fortune. But young heads are on young shoulders; it was not to be, and who cares?”

Who cares? The answer is, Mr. Adams cares. He cares so much in fact that he sedulously minimizes, or rather tosses aside, The Birds of America—its completion he describes as “anticlimax”—in order to concentrate on Audubon’s many early lapses and failures as a business man. He even so far departs from truth as to make Audubon’s later enterprises seem virtual failures, too. To justify his carefully slanted thesis, Mr. Adams utters a judgment that gives him completely away, a sentence I shall treat as final. “Yet for all his cavalier attitude toward his firm, John James was seriously interested in making money. What he wanted was to be a successful merchant, a man of wealth. Yet he would not work at it.” This statement needs only one correction: It is Mr. Adams who wants him to have been a successful merchant and a man of wealth; and his own meticulous citations prove that Audubon never cherished any such ambitions; for the overwhelming passion of his life, from earliest childhood on, was his love of birds. To that he was ready even to sacrifice his Lucy. The biographer who could ignore the massive evidence of Audubon’s whole career in order to make this preposterous interpretation of Audubon’s ambitions should have stopped in his tracks when he had written those words. But since he went on, we must ask Rufus Wilmot Griswold, the studious defamer of Poe, to move up and make room for Mr. Adams.

What Mr. Adams steadfastly regards as a wanton miscarriage of Audubon’s opportunities and a betrayal of his duties to his wife was in fact what ensured Audubon’s final commitment to his true vocation. But in addition Audubon’s passage to his life work was favored, at intervals, by a series of chance promptings that registered as deeply as those childhood traumas that sometimes mar a whole life. Though Audubon hated his father’s American agent Dacosta, indeed once wanted to murder him, he recorded gratefully that Dacosta’s praise of his drawings and his prediction of a great career as a naturalist, helped set him on his road. So, too, a few years later in 1810, a chance visit of the Scots ornithologist, Alexander Wilson, fortified Audubon’s confidence in both his own ambitions and his draughtsmanship. Finally, it was a remark by an English traveler, Leacock, in 1822, that helped crystallize Audubon’s determination to seek publication and patrons in England.

THE ONE INCONTROVERTIBLE FACT about Audubon’s life, then, is that his passion for birds absorbed and determined his whole life, even though he had talents and sensibilities that spread in many directions, including quadrupeds and butterflies. It was because this passion for birds was so engrossing, as unreasonably engrossing as Dmitri’s obsession with Grushenka, that his work transcended his disabilities as a painter or a scholar. Apart from the occasional “normal errors” that even painstaking observers make, Audubon, in the judgment of his peers, from Baron Cuvier to Robert Cushman Murphy, was a supremely good ornithologist. While still an amateur Audubon maintained the most exacting standards in observing the behavior of birds, making on-the-spot records, opening their stomachs to discover their feeding habits, even studiously sampling them as food, for the further light their taste or texture disclosed. Even the study of bird migrations begins with Audubon, for he was the first naturalist to band young birds, to find out if they returned to their original habitat. “Nature,” Audubon said, “must be seen first alive and well studied before attempts are made at representing it.” That practice separates him from Buffon and Linnaeus and brings him close not only to Gilbert White and Thoreau but to Darwin and Wallace.

Certainly one side of Audubon might tempt a shallow biographer to characterize him as the typical romantic personality: passionate, impulsive, willful, lonely, convention-breaking: but nothing would conceal the real significance of Audubon’s life and work so easily as this cliché. Yet at first glance, he seems a figment of Chateaubriand’s imagination; or even more, he seems a robuster version of Rousseau; for besides their common love for wild nature, there was a certain similarity in their delicate mobile features, their hypersensitive proud natures, their fine ability to make enemies and become the objects of real—not fancied—persecution, such as Audubon suffered from George Ord and Charles Waterton, who hounded him as wantonly as Cobbett hounded Dr. Benjamin Rush.

Audubon loved his life as a genuine American backwoodsman: he took to the buckskin costume of the Western hunter as Rousseau less appropriately did to that of the Corsican mountaineer; and he disciplined himself to a stoic indifference to rain, cold, fatigue, hardship, as Rousseau sought to discipline Emile. On Audubon’s first trip to England, he proudly kept to the Western style of long hair reaching down to the shoulders, as Buffalo Bill did long after him. When Audubon finally, on the pleadings of his Scots friends, assented to being shorn before leaving Edinburgh for London, he recorded the event in a sorrowful epitaph, surrounded by a heavy black border. It reminded him “of the horrible times of the French Revolution, when the same operation was performed upon all the victims murdered at the guillotine.”

But where birds were concerned there was nothing willful or romantically sentimental about Audubon: He never flinched from killing or dissecting them. He concentrated upon condensing in graphic form his hard-won observations, line by line, feather by feather, and was as interested in the vulture disemboweling his victim as in a male turtle dove feeding or showing fondness to his mate. Except for a brief period in his youth in the atelier of Jacques Louis David, and later instructions in oil from John Stein and Thomas Sully, Audubon was self-taught; and in the interests of accuracy used pencil, pastel, water-color, even oil on the same picture, to capture the sheen of plumage or the beady gleam of an eye. In his efforts to make his paintings faithful to the object, he was his own harshest critic, ruthlessly destroying or copying over work that did not satisfy him. His performance was not an emotional expression of the romantic ego; it was as self-effacing as the late Artur Schnabel’s interpretations of Beethoven: the personality dissolved into the music.

THE PAINTING and the eventual engraving of The Birds of America is a saga in itself. For it was one thing to make ready the great collection he took to England in 1826, and another to have them reproduced accurately and handsomely, while securing subscribers willing to pay £174 for the whole series of 435 plates—over a thousand birds. (In the United States the price was $1,000.)

Any conventional business man might have quailed before the task Audubon undertook. Arriving in a strange country, only his capacity to make friends and to work to the point of exhaustion enabled him to survive. So far from showing incompetence in his business affairs, as he had done in the absurd misfit role of shopkeeper, Audubon now mastered every detail of his job, pocketing his touchy pride, seeking introductions and subscribers in every corner of Britain, meeting many rebuffs but cannily using every opportunity. Within a year he had commenced publication, and within a dozen years, the eighty-seventh part of The Birds of America, which completed the fourth volume, was published.

By his own exertions Audubon had not merely launched his life-work but had achieved a sufficient income to persuade his wife to join him in 1830. In a little while, he re-established his whole family and drew his sons, who shared some of his talents, into the work; for Victor, the elder, and more especially John Woodhouse, the younger, both trained themselves as his assistants—indeed even when fifteen John had shipped him skins for sale or gift in Britain. In that sense, the whole work became a mighty labor of love: one that makes mock, incidentally, of the oedipal fixations of our own generation. And the fact that both sons married daughters of Audubon’s close friend and colleague, John Bachman, only makes the joke on Freud a little more pointed. Once the birds took their rightful place in Audubon’s life, even his shaken marriage was redeemed.

The fact that Audubon heeded the lessons of adversity and completely made over his life in order to fulfill his vocation and restore his marriage is even more astonishing than his actual ornithological achievement and widening influence as naturalist. Once embarked on the publication of The Birds of America, he mastered every part of his formidable task. He chose the right engraver, supervised the coloring of the plates—at one time fifty painters were employed, and once they all struck because he had criticized the sloppy work of one of them—he solicited subscriptions, appointed agents, saw that bills were collected. On top of all this he not merely painted the many new pictures needed to make the work as complete as possible, but went on further explorations, in New Jersey and Florida, and even chartered a ship to carry his search to Labrador. And once Audubon had surrendered to the demands of his life-mission, even his practical judgment proved shrewder than that of his professional advisers. Against the warning of Bohn, the famous bookseller, he chose the grand form of his first elephant-size folio and priced it at a “prohibitive” cost a set, despite the competition of cheaper posthumous editions by his able forerunner and rival Alexander Wilson. That daring decision to spare no expense went flat against sober business judgment—and proved much sounder.

The man who by his own exertions and his own ability could lift himself out of the financial morass into which he had sunk in 1819 was no ordinary man, and certainly no flighty, self-indulgent romantic. To characterize such a life as a failure, as Mr. Adams does up to the very end of his book, is to present a venomous travesty of the truth. No one could have had a juster view of his own talents and limitations than Audubon himself. In 1830 he wrote in his journal: “I know that I am a poor writer, that I can scarcely manage a tolerable English letter, and not a much better French one, though that is easier to me. I know I am not a scholar, but meantime I am aware that no man living knows better than I do the habits of our birds; no man living has studied them as much as I have done, and with the assistance of my old journals and memorandum books, which were written on the spot, I can at least put down plain truths which may be useful and interesting, so I shall set to at once. I cannot however give scientific descriptions, and here I must have assistance.” Audubon’s capacity for friendship served him well here. Where he was weak, William MacGillivray, the young Scots naturalist, and Bachman, of Charleston, South Carolina, a well-schooled American naturalist, supplied the missing scientific notations.

AUDUBON’S ACTUAL LIFE had an epic quality that the American poets of his time dreamed of: It prefigured, in the act of living, the message of Walden, “The Song of Myself,” and Moby-Dick, dramatically uniting their themes and adding an essential element that was unfortunately lacking in all three: the presence and power of woman and the ascendancy of love. So far only Constance Rourke, with her insight into frontier life and its humor, and Van Wyck Brooks in The World of Washington Irving, have in any degree captured the spirit or taken the measure of this man, though perhaps the quickest way to come close to him is through his few salvaged journals—most of them were destroyed, supposedly in the great New York fire of 1835—now published in a Dover edition.

When one views Audubon’s personality and work as a whole, there is little that needs be apologized for or explained away. Even his large carefree gestures are merely those of a large soul, though they may irk those who do not understand his particular combination of humility and self-confidence, tenderness and toughness, loving care and ruthless neglect, his audacious high spirits and his “intemperate practice of temperance,” as he himself put it, Even in his lifetime, the man was almost a myth; and that fact doubtless tempted some of his ornithological adversaries to treat his exact observations as if they, too, were falsified or inflated. But the real Audubon is even bigger than the myth.

What makes Audubon the important figure that he still is, now perhaps more than ever, is that his life and work brought together all the formative energies of his time, romanticism and utilitarianism, geographic exploration, mechanical invention, biological observation, esthetic naturalism, and transposed them into consummate works of art which, like the works of Turner, Constable, and Edward Lear, constantly transcended their own naturalistic premises. In the Ornithological Biography, which he published as a companion to his Folio, and republished in the later “miniature” edition of The Birds of America, his very absence of system enabled him to give a fuller account of natural processes and functions than any more abstract approach permitted: for the included the observer as well as the object observed. If, to later scientists, he seemed the last of the old-fashioned naturalists, he has now become the first of a new breed of ethologists, among whom Tinbergen, Lorenz, and Portmann are perhaps best known.

Similarly, Audubon was a practicing ecologist, long before the name and the science were established as such. For almost a century before museums of natural history showed their specimens in natural postures against their natural habitat, Audubon depicted them in this fashion. Even his passion for birds has a new significance, for since Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, we realize as never before that the presence of birds is the most sensitive possible index of a well-balanced human habit, with sound practices of settlement and cultivation; while their absence indicates an organic imbalance, brought on by reckless deforestation, defoliation, pollution, and poisoning.

Finally, like the Bartrams and Wilson before him, and like George Perkins Marsh, John Wesley Powell, and Frederick Law Olmsted after him, Audubon is one of the central actors in the conservation movement. He not merely demonstrated the richness of primeval America, but preserved as much of it as possible in lasting images of its flowers, shrubs, insects, butterflies, as well as birds and mammals. At a moment when only striking landscapes—high mountains, craggy gorges, shaggy forests—were singled out for admiration. Audubon, like Thoreau, was equally sensitive to the swamp, the bayou, the prairie. And if we manage to protect any part of the primeval habitat from the bulldozers, the highway engineers, the real estate speculators, and the National Parks bureaucrats, eagerly defiling what they are supposed to preserve, it will be because Audubon stands in the way, reminding us that this birthright must not be exchanged for money or motor cars.

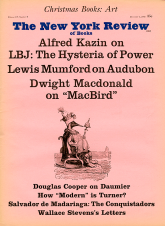

IN SKETCHING the main lines of Audubon’s life I have been moved only partly by the desire to redress in anticipation Mr. Adams’s distorted picture, but even more by wishing to give the new two-volume edition of his painting an adequate biographic setting, which the pious activities of licensed bird-watchers and nature lovers often tend to obscure. There have been various editions of The Birds of America, besides the great elephant folio. The present edition is far easier to handle, it goes without saying, and it is more ample in format than the “miniature” edition that Audubon brought forth when the big plates were done. What gives the American Heritage edition a special distinction is that it is derived, not from the folio, but from the original paintings which the New York Historical Society bought for a pittance from Audubon’s widow.

Some of the best pictures are the same in both editions: the birds are always Audubon’s. But Audubon, with good sense, entrusted the surrounding details, of foliage and landscape, to his helpers, especially to his inspired engraver, Robert Havell, Jr. He would say: “Draw a grasshopper” or “show some rotten wood” and Havell would provide a well-drawn grasshopper or tree stump—features that are missing in these originals. Their absence, however, only brings out more sharply Audubon’s own graphic mastery.

Though Audubon was keenly interested in trees and plants, and could paint them, the painting of birds drained his best energies; and, like any Renaissance artist, he left the subordinate details to various assistants, even before he assembled his portfolio for printing: notably to young Joseph Mason, in the early Twenties, later to George Lehmann, a Swiss from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and still later to his sons, particularly the younger, John Woodhouse. For the most part the flowers, leaves, stems, and tree trunks are beautifully drawn, sometimes in the later illusionist manner of William Harnett. These reproductions show that a fine union of rigorous drawing and keen observation was common in this early period, before photography had begun to discourage the amateur artist. Occasionally the leafage is so well rendered that it distracts the eye from the birds and reduces their esthetic importance.

But in landscape foregrounds and backgrounds, which require organization and design of a higher sort, Audubon could not command, in either Lehmann or his younger son, a talent equal to his own. At times the poor texture of the grasses or the wishiwashiness of the sky contrasts glaringly, in their seeming haste and carelessness, with Audubon’s meticulous drawing. If only Edward Lear had been his co-worker!—the Lear whose landscapes in the Benaki Museum are almost worth a visit to Athens. Only when Audubon could leave the background to Havell, who was an admirable painter in his own right, are the larger plates adequate. In this respect, as well as in their naturalistic completeness, the engravings of the elephant folio are, paradoxically, superior to the original paintings—though Audubon sometimes thought Havell’s colors were better, too.

But in any event, whether original painting or aquatinted, handcolored engraving, whether perfect or imperfect, this grand collection of pictures must not be under-rated as works of art. These pictures reveal no debased photographic realism, but realism in the medieval scholastic sense—the essence of a hundred different perceptions of birds fused by the mind into a single conceptual image, graphically presented. No camera eye can perform this feat, only the human brain, bringing to bear the experience of a lifetime. Except in the case of the life-sized birds, which must be presented on double pages, this new edition is not just a satisfactory compromise, but a beautiful performance in its own right. At the price asked in the inflated currency of war-time, it is dirt cheap.

This Issue

December 1, 1966