Although there is little question about the importance of the period between the Civil War and the Great War, that half-century contains the greatest hazards for the American literary historian. “Our modern literature,” Alfred Kazin pointed out twenty-five years ago, “was rooted in nothing less than the transformation of our society in the great seminal years after the Civil War…in those dark and still little-understood years of the 1880s and 1890s when all America stood suddenly, as it were, between one society and another….” But Kazin himself despaired of telling “the whole story,” and apologized at the beginning of On Native Grounds for making only a tentative intrusion on the rhythms, the landscapes, the sensibilities that make up “what it has meant to be a modern writer in America.”

In the Twenties Parrington had glumly said that no scholar was yet equipped to write American literary history, and he himself died leaving unfinished the third volume of Main Currents in American Thought, which was to cover the years between 1860 and 1920. The poorest of Van Wyck Brooks’s histories was his last: The Confident Years: 1885-1915, which in spite of its title, conveyed confusion rather than confidence. Only Granville Hicks seems to have had no qualms about his own interpretation of American Literature since the Civil War. For, writing in the Thirties, he was confident that final shape had been given what he called The Great Tradition by the “revolutionary movement in literature” of his own day.

To the detriment of American literary history, “pure” criticism and biography have more recently attracted most of our best critical minds—with the always eccentric, always important exception of Edmund Wilson. Yet nothing would so sharpen criticism or enliven scholarship as the selecting and placing demanded by literary history. How necessary this is daily demonstrated to the hardy soul who observes the teaching of literature in the American high school—an experience that literary men might find as unsettling and as challenging as our scientists found it ten years ago when faced with the debasing of their own subject in the schools.

Word has somehow got out to English teachers that Literature is a transcendent thing, triumphant in its greatness over the petty concerns of time and place. Order, discrimination, and reality have therefore been allowed to vanish from the school syllabus, which assigns Macbeth a month before Kon-Tiki and after “The Gold Bug,” or inserts a novel by Hardy (there is nearly always a novel by Hardy) between The (adapted) Odyssey and Profiles in Courage. Chronological order is shunned as if it were an artefact imposed from without by pedants, and to take pride in the national quality of their own literature is regarded by our best teachers as the worst sort of provincialism. The failure to present the American tradition to the American young may, however, be the last gasp of American provincialism. Yet the English professors who looked into school English on assignment from the Council for Basic Education were so appalled by the historical materials available to the classroom that they recommended giving up entirely the enterprise of teaching American literature as part of the national culture. Instead of trying to work a revolution in the schools, as the physicists did, they opted out with the lame excuse that “chronological and geographical arrangements tend to pervert the study of literature.”1 Such a statement would simply be untranslatable into French, or any other literary language.

To say, therefore, that the works of literary history under review have serious pedagogical value is a compliment of some magnitude. All shoulder the responsibility of establishing a literary continuity between the glories of the American 1850s and those of the 1920s. In Harvests of Change, a work of wide learning and critical sophistication, Jay Martin has, in the Parrington tradition, boldly taken on the entire period between 1865 and 1914. For us to ignore its rich literary harvests of unprecedented social changes, as Professor Martin demonstrates, would be to act out a Bellamy fantasy: that is, to fall asleep nodding over Hiawatha and The Scarlet Letter and wake up clutching in alarm copies of The Waste Land and The Sun Also Rises. “If you had told me,” says the hero of Looking Backward, “that a thousand years instead of a hundred had elapsed since I last looked on this city, I should now believe you.” “This city,” however, would be not Boston, but New York.

IN THE FIRST DECADES after the Civil War the tempo of literary change was slow and deliberate, a time echoing with the voices of Whitman and Lincoln. The Seventies and Eighties were dominated, it is now clear, by three writers—Mark Twain, Henry James, Howells—who seem from their writings, almost to have passed abruptly from childhood to a long and lonely middle age. But as the end of the century approached, a new generation arose which can be thought to have lived nothing but its youth. Partly because of the early deaths which cut off much of the promise of the fin de siècle (Crane, Norris, Boyesen, Frederic all died young), Larzer Ziff calls his lively and sensitive study of the American 1890s, “the Life and Times of a Lost Generation.” But there was nothing lost about the decade in the sense of literary consequence. Professor Ziff is right to set off the Nineties as the pivot between old and new, for “somewhere between Haymarket and the Columbian Exposition of 1893,” as Kazin wrote long ago, “the modern soul had emerged in America.”

Advertisement

Disorder and tragedy were hazards of the fin de siècle elsewhere than in America, as was the dizzy speeding-up of literary events. Donald Pizer has done much to unravel the tight chronology of the 1890s by documenting the rapid flights of Hamlin Garland between East, North, and West, criticism, art, and politics, Howells and Crane. His valuable essay on the Garland-Crane relationship is now collected, along with a dozen other thoughtful studies of post-Civil War fiction under the title, Realism and Naturalism in Nineteenth-Century American Literature. In these essays, and in his new study, The Novels of Frank Norris, Professor Pizer does credit to the passion with which the novelists searched for scientific and philosophical answers to the aesthetic problems inherent in the subject matter of social change.

Realism and naturalism are useful, if somewhat stale, labels for the writer’s confrontation with change. This confrontation could as well be called, as Robert Bremner has demonstrated, The Discovery of Poverty in the United States.2 Coming later to America than to Europe, yet earlier in its modern guises, that anguished discovery must be the starting point for any discussion of literary America between the Wars or in the Nineties or in Naturalism. For in a hundred gross and subtle ways the writer’s sensibility was shaped by the shock of poverty: poverty against myth, against plutocracy, against progress, against morality, against me, as Howells heard Tolstoy cry. The writer’s painterly eye—and the artist’s literary one—focussed in the early Nineties on poverty’s numerical power. At the time when writers felt they had to move to New York, the city held 50,000 bums: 14,000 nightly looking for a Bowery bed, lines of 2,000 stretching toward a charity loaf on lower Broadway, more beggars on Fifth Avenue and in Central Park than Howells remembered seeing in Venice. These were the pictures that terrified both Dreiser and Crane (for all their differences in background and temperament) in 1894, the year of the worst depression America had known, and the year Dreiser and Crane both turned the impressionable age of twenty-three. New York was four-fifths immigrant (including the immigrant’s child), and the Lower East Side achieved the highest density in history: almost 3,000 to the square mile. Writers followed Riis and Roosevelt down to the East Side to look at what Henry James called our national pot au feu: it was on the Bowery, and not in the Naturalist school of Paris, that Crane said he had picked up his “artistic education.”

The countryside was infested with tramps’ and the Midwest in particular (as Turner solemnly announced the closing of the frontier) with back-trailing farmers: 18,000 wagons came East across the Missouri in one year. These specters appeared to Jack London and Josiah Flynt, to Garland and Robinson; Frost saw them “huddled against the barn-door fast asleep. A miserable sight, and frightening, too—You needn’t smile—“ Even the apotheosis of the cowboy, which belongs to the turn of the century, owes something to the wonder and terror of tramps.

Starting in the Eighties there were in this country about six thousand strikes a year: they were what Bellamy’s hero fell asleep to forget. At a time when writers read newspapers with professional dedication, the headlines daily told that strikes were being fought, bombs thrown, anarchists hanged, policemen brutalized, capitalists knifed, and a President assassinated. Howells wrote of the “frenzy and cruelty, for which we must stand ashamed forever before history. But it’s no use. I can’t write about it.” Few novelists could, directly: it was perhaps emotional insensitivity that made James one of the few serious writers of the period to take on the subject of revolution, just as, in our time, Katherine Anne Porter has been one of the few to take on the Hitler era. Howells, Norris, and London failed in their attempts at scenes of industrial violence; Dreiser could do it only obliquely, through the dulled eyes of Hurstwood; and Crane merely dreamed of making “the scene of the next great streetcar strike” into something that would “dwarf the Red Badge, which I do not think is very great shakes.” The judgment was foolish, but the implication both serious and central to literary history; war and the badge of violence were linked to the crisis of poverty in the iconography of Crane’s generation.

Advertisement

BY DOCUMENTING poverty so well, Martin’s literary history gains weight and balance, notably in his discussion of utopias, where he makes a critical case for many utopian and distopian pages in Howells, Bellamy, and Henry Adams. (Had he concentrated on major works and discarded many of the minor ones, the case would have been even stronger.) In his introductory chapter, “Land of Contrasts,” Ziff threatens to miss the drama of the Nineties: his “contrasts” are merely quaint, and do not include the horror of the gap between rich and poor that first appeared to the men of the Nineties. But his history gains seriousness as well as momentum as it goes on, and he gradually builds up enough of a sense of “the phenomenal abrasiveness of the Nineties” to set off his splendid concluding chapter on Sister Carrie. There Ziff shows that Dreiser’s ability to “construct life from fragments” was the culminating achievement of a shattering decade.

Mr. Martin demonstrates how much the poems of Frost and Robinson and even Emily Dickinson gain from being placed historically in the abrasive between-wars period, rather than being considered misfits. (For this reason, he should have included Willa Cather, Gertrude Stein, and James Weldon Johnson). These histories do exceptionally well, too, with the theme of urbanism, because they deal with the challenge as well as the rebuff that the city brought to American writing. Because he sees the town as well as the frontier in the minds of Mark Twain’s American boys, Martin can show their kinship to the American girls of Henry James—a suggestive point about which Ziff and Pizer also have good points to make.

Urbanism, in fact, seems more useful in ordering late nineteenth-century literature than the theme of regionalism, which, from Parrington to Martin, has laid a deadening hand on literary history. Most pre-1890s “local color” writing now seems of little literary importance—Sarah Jewett shows to better advantage as a woman writer (along with that other presumed “regionalist,” Willa Cather). The development of San Francisco, Philadelphia, and Chicago as art and intellectual centers is at least as interesting as that of their prospective “regions.” The theme of urbanism, in addition, enables the literary historian to talk seriously about the architecture of Sullivan and Wright, the paintings of the Ashcan School, the photographs of Steiglitz, the decor of Tiffany, the golden age of opera and popular music, which fill the literature if not, alas, the literary history of the turn of the century.

In his interesting chapter on Santayana, Herrick, and Robinson, Ziff makes imaginative use of the trek in the Nineties from Harvard to Chicago University, but both he and Martin slight the shaping geographical fact of the decade: New York’s displacement of Boston as the nation’s literary center. That story includes the immigrant and the outsider, the movement against gentility, the poverty and plutocracy, the art and the music and the pop culture which have always made New York’s literary life different from Boston’s—or London’s. The New York story also includes the revolution in publishing and journalism, which deserves something better than the snobbish and inaccurate handling it receives in most literary histories. Rather than repeat unsupported clichés about the “quick, slick” journalism “that could rust out a writer’s style,” Ziff might have looked harder at works of literary journalism like Artie and Children of the Ghetto with some measure of the respect accorded them by Edmund Wilson and Irving Howe.

Also still untold is the story of the literary creation of the American language, the authentically “great tradition” that enfolds Lincoln, Whitman, Dickinson, Mark Twain, Howells, James, Ade, Crane, Robinson, Dreiser, Frost, Stein, Eliot, and Hemingway. Like the new subject matter, the making of a new language was the concern of the new breed of literary men—most of them products of new families, new colleges, new copyrights, newspapers—who descended on New York in the Nineties. They were described by Howells’s favorite writer as

Rash inconsiderate, fiery voluntaries,

With ladies’ faces and fierce dragons’ spleens…

Bearing their birthrights proudly on their backs,

To make a hazard of new fortunes here.

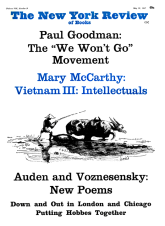

This Issue

May 18, 1967

-

1

James J. Lynch & Bertrand Evans, High School English Textbooks: A Critical Examination, Little Brown, 1963, p. 142ff.

↩ -

2

From the Depths: The Discovery of Poverty in the United States, New York University Press, 1956. Bremner’s important work of social history is now available in paperback to historians of American arts and letters.

↩