Born in 1469 of an aristocratic but impoverished Florentine family, Niccolo Machiavelli saw in his youth the brilliance of Florence under the benevolent despotism of the Medici. He seems to have been unaffected by the Neoplatonic revival, for his formation was that of a purely Latin humanist, and the two passions of his life were for politics and history, inextricably mingled. When the Medici were expelled, the change to a republican government fostered such interests, for the intense political discussions which went on in liberated Florence drew constantly on examples from ancient history. Machiavelli gained his early political experience as a secretary to the Florentine republic; on the return of the Medici he was imprisoned and tortured, though soon released. He retired to his small estate where, in great poverty, he mused on what had happened, asking why the Romans had succeeded in building a great republic and empire whereas Florence and all Italy were going down into ruin. The result of these questionings was The Prince and the Discourses on Livy.

Describing in a letter his life at this time, Machiavelli says that he escapes from this hard world when he enters his study; there he puts on better garments to converse with ancient authors, and loses himself in delight. So might Petrarch have described the solace which he found among the classics. But there was a basic difference between Machiavelli’s approach to the ancient examples and that of Petrarch and the humanist historians. In the earlier humanist tradition, as in the Middle Ages, the stories about the great men of antiquity had been used as images of virtues and vices, teaching ethics by their examples. Machiavelli seeks to learn from them political counsels; he writes his commentaries on Livy, comparing ancient with modern events “so that those who read what I have to say may the more easily draw those practical lessons which one should seek to obtain from the study of history.”

MACHIAVELLI BELIEVED that history always repeats itself, and tried to draw up maxims for political conduct in given sets of circumstances from the analysis of similar circumstances in the past. It may be questioned whether he was as much a “realist” as his great contemporary, Guicciardini, who dealt with each situation as a new problem, not soluble by rules, and who criticized Machiavelli’s maxims. There is moreover a strong poetic and imaginative streak in Machiavelli, which is hardly consonant with pure realism. This streak comes out in one of his favorite themes, the virtù of the Roman people. He uses this word in a Latin sense, not translatable as “virtue,” to include confidence or morale, efficiency and strength of character, even the “virtue” of loyalty when used for the Roman attitude to the state or the army. The Romans possessed virtù longer than any other people; hence they lasted longer and triumphed longer over fortune. Thus intangible elements enter into Machiavelli’s view of history, and no very clear answer can be given to the question of what virtù is or how it is kept or lost, except that there is a connection between virtù and religion. The religion which Machiavelli most admires is Roman paganism because it subserved the state and contributed to maintaining the morale of the legionaries. This brings us to one of his main maxims: the authority of the state is maintained by force; the best mode of maintaining authority at home and developing it abroad is through an army, which must be formed of citizens of the country, not of mercenary troops. Rome, of course serves as the great example, and the formation of a citizen army for the defense of Florence was one of Machiavelli’s dearest projects (though not his invention).

Reviving an argument used in the days of the barbarian invasions, Machiavelli thinks that Christianity weakens virtù. His attitude to Christianity is, however, complex. To understand it we must take into account the examples which he saw before him in contemporary Italy, the papacy in its most corrupt phases just before the Reformation. It is the papacy, he thinks, which is a prime cause of the weakness of Italy and of the decay of religion in Italy, which in turn has weakened virtù. Northern provinces have kept a purer religion because they are farther from the corrupt center. Such remarks have suggested to some that Machiavelli was a political version of Luther; this comparison will not really work but that it could have been made at all shows how complex is the question of Machiavelli’s attitude to religion.

He was a great reader of Dante, and one should not study his politics without taking a look at those of his fellow Florentine. Dante believed that the Roman people had been chosen by God, because of their virtue (in the normal sense of the word), to be the state which prepared the way for the coming of Christ, who was born in the reign of Augustus. He believed that the divine mission of the Roman empire was continued in the medieval successors to the imperial title, and he called upon the contemporary Emperor to come as a savior to Italy to reform the corruptions of the Church. It was precisely visionary politics of this kind which Machiavelli set out to attack; the visionary imperialism of the Dantesque type was, he thought, a cause of Italy’s weakness because it encouraged her to appeal to foreigners and foreign armies rather than strengthening her own virtù. Though Dantesque politics are thus the antithesis of those of Machiavelli, yet something of the old belief in the religious mission of the Romans enters into Machiavelli’s admiration of their great example.

Advertisement

One reason, according to Machiavelli, that the Florentine republic was lost was that Piero Soderini was too honest and good a man to take certain steps. This example brings us to the great Machiavellian crux, that dishonest or even criminal action cannot be excluded from the conduct of politics. Take another example. Romulus murdered Remus (Machiavelli does not distinguish between real and mythical history). It is characteristic of Machiavelli’s honesty that he insists that Romulus was supposed to have done away with Remus. And it is also characteristic that, having emphasized that it was murder, he also insists that Romulus was justified, since Rome had to be under one ruler. The necessity for one ruler was actually one of the mystical Dantesque arguments; Machiavelli will not disguise the reality of the seizure of power by one.

In The Prince, a new prince is out to seize power and Machiavelli describes the stratagems which he employs, such as ways of evading treaty obligations, and the liquidation of opponents who might be dangerous. He advises that the prince should always give religious reasons for his actions, masking the reality of violence on which his power is based in fair seeming words. Machiavelli cites, as the modern example of a successful new prince, Cesare Borgia, who carved out a dominion for himself by unscrupulous methods. Controversy has raged around The Prince. Had Machiavelli ever hoped that some new prince, beginning with the Romulus technique, would restore Italy to the rule of one and so revive her virtù? The last chapter of the book calls passionately for a “savior” in an almost Dantesque style. Those who have wished to see Machiavelli as a cynic have to get rid of that last chapter as an irrelevance. But it is led up to by what goes before and was evidently intended as the last word to the book.

In the Discourses, a more important work for his political theory than The Prince, Machiavelli is concerned with republican theory and practice. He was himself a republican, believed in popular government, and hated tyrants. There seems to be contradiction between this attitude and his apparently complacent account of the methods by which a prince seizes power. We have to remember that Machiavelli’s thinking was closely conditioned by Roman history in which a republic turned, via Caesar, into a principate and an empire. He has to analyze both types of Roman political examples, leaving his own attitude in some obscurity. It is, in fact, one of the chief problems confronting the student of Machiavelli that no coherent system can be drawn from his works. They are full of contradictions: he was not a systematic thinker, though later commentators have tried to systematize him. Certainly no clear cut system of political amoralism can be drawn from him. When speaking of settled governments, he gives to rulers quite opposite advice to the counsels in The Prince, arguing that it does not pay to make enemies by cruelty and putting forward as the right examples the good and humane characters among the Roman emperors. Sometimes he will say that all men are evil and must be restrained by force: at other times he speaks of the “good” Romans. Machiavelli never calls evil good, nor vice virtue. He recognizes and accepts the normal morality. But he does say sometimes (not always) that the politician, in order to be successful, must be prepared not to be good, must be ready to perpetrate fraud and even crimes. It is with sorrow that he states this, and he advises the man who wishes to keep his conscience pure not to meddle with politics nor aspire to seize power.

THE REACTION of the Elizabethan dramatists against the “wicked Machiavel” is understandable. Particularly in England, where the idea of the Monarch as God’s representative on earth was being raised to even greater heights, the contrast between the idea of the prince as the divine fount of wisdom and virtue and the Machiavellian Prince must have seemed devastating. At the heart of Shakespeare’s meditations on monarchy there lies tension between the prince as an example of virtue and vicious distortions of that example. Machiavelli had taught Shakespeare’s generation to face realities about the nature of power, resulting in an extension of moral consciousness in the political sphere, rather than the reverse, a more subtle and profound analysis of historical examples than the old rigid exemplarism could afford.

Advertisement

Machiavelli died in 1527, the year of the sack of Rome by the armies of the Emperor Charles V, which marked the end of the independence of Italy, the end of the Renaissance in the land of its birth. Machiavelli’s statecraft can be seen as the last attempt by humanism at the defense of Italy from the barbarian invasions. Retreating into the study to learn political skills from historical examples was a scholar’s way of meeting a situation which, as Machiavelli knew full well, demanded force and virtù. But this late effort of the humanist spirit laid the foundations of a new science, the science of political theory.

Since the Second World War, a large volume of scholarship has transformed our knowledge of those aspects of the Renaissance out of which Machiavelli came. The intensive development of history as a branch of rhetoric by the humanists, resulting in a mass of history writing in imitation of historical models, is a movement whose outlines are now becoming clearer. The origins of the transition from rhetorical history, with its strong exemplarist tinge, to the realist approach of Machiavelli and Guicciardini are to be found in the political history of Florence during the period, in the discussions of real political problems by men imbued with the Florentine critical spirit and deeply versed in the traditions of Latin humanism, of which Florence had been one of the main centers. The late Delio Cantimori’s studies of Florentine civic and political thinking, and the work on Florentine documentary sources done by Felix Gilbert and Nicolai Rubinstein, have shown how many of Machiavelli’s themes (including virtù) were commonplaces in the discussions which went on constantly in Florence. This does not diminish Machiavelli’s originality, nor his status as the first to give literary expression to a new approach to politics and history. But it should ultimately dethrone all the fictional Machiavellis of the past, not only the “wicked Machiavel” but also the Machiavellis over-systematized by much later philosophies and theories of political science. We now know that the true Machiavelli was the political humanist.

FICTIONAL MACHIAVELLIS, however, are not yet dead, for Guiseppe Prezzolini presents one in the book under review. Ignoring most post-war scholarship. Prezzolini sees Machiavelli as anti-christian and atheistical, believing in nothing save amoral political force, the realities of which are masked from the simpleminded. He wishes to open our eyes to the realization that Machiavelli is “our contemporary.” Among his reasons for this identification are the following. The modern state encourages all religious denominations while believing in none of them. It is based on amoral force as the root of political power; even “the draft” is fathered by Machiavelli for it is the modern counterpart of his citizen army. These curious parallels seem to have little to do with the genuine Machiavelli, but are based on something like the old lay figure of the atheist and cynic. About half of the book is concerned with a survey of Machiavelli’s influence, covering all periods and all countries, arranged under headings such as Machiavelli in England, France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Russia, America. Wide reading has gone into the collection of this material, and much of it, particularly the quotations, is extremely interesting. As the author says, there is no modern book on Machiavelli’s influence as a whole; he has attempted to provide such a book on a popular level. Reading it one gains a very strong impression of the immense, indeed vital, importance which such a survey might have. The index to this book could provide a rough guide to the writers and personalities who are significant for this history, and there are attempts at dealing with transformations of Machiavelli’s thought, by, for example, German philosophers, or in the Italian risorgimento. But his breaking up the themes into more or less disconnected sections makes for incoherence; and some extremely serious issues are evaded. For example, there is only one mention of Mussolini. Above all, the writer’s own brand of superficial Machiavellianism precludes his making a serious approach to the moral issues.

As a corrective to Prezzolini, American readers could refer to the chapter on Machiavelli in Sheldon Wolin’s Politics and Vision (1960) which is fully sensitive to the tragedy of Machiavelli’s vision of violence, and rightly presents his effort to create a science of politics as, basically, a moral effort toward enlarging man’s control of political forces and directing them into beneficent and constructive channels. As Machiavelli’s last word on the prince, I quote the following from the Discourses:

To reconstitute political force in a state presupposes a good man, whereas to have recourse to violence in order to make oneself a prince in a republic presupposes a bad man. Hence very rarely will there be found a good man ready to use bad methods in order to make himself prince, though with a good end in view, nor yet a bad man who, having become a prince, is ready to do the right thing and to whose mind it will occur to use well that authority which he has acquired by bad means.

Machiavelli was not an amoralist; to read him is not to enter a grey mental climate where ethics dissolve in philosophies of power, but to become more sharply aware of the problem of evil in relation to political force.

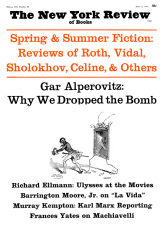

This Issue

June 15, 1967