Washington, D.C. is Gore Vidal’s tenth novel. Go to the Widow-Maker is James Jones’s fifth. When She Was Good is only Philip Roth’s second, but he is young, and this book, with Letting Go and his volume of stories, Goodbye, Columbus, puts him in company with Jones and Vidal among the small group of novelists who are at once serious, prolific, and best sellers. Sometimes we have to remind ourselves that novel writing is still a career that can be both honorable and profitable.

These three writers work largely within the long tradition of their profession. Their books have characters, settings, and plots. None of the three writers is much concerned with twentieth-century innovations in technique, or with experiments—although Jones in his reckless way is often out on a sort of adventure, or experiment, in this new book. They are not primarily engaged in recording sensibility, or in complexities of appearance and reality, or in fantasy, fable, symbolism, or other representations of the unconscious. As for style—well, except again for Jones, in his way, and with some tonal variations for Roth, they are content with the present conventions of standard English prose.

They tell stories. The stories are about people who cast shadows in a world we are supposed to take as real. To persuade us that these people and these worlds are real, they use the conventions we have learned to accept in novels as representing realities, as representing indeed for a time at least something like our total experience. They give us a mixture of what we might otherwise call history, psychology, morality, with a whole system of vocabulary—where did it come from?—of physical description, of states of feeling and how we learn of them, of what ought to be or what ought not to be: and we swallow it whole. For a few pages we may notice these conventions as the author gets us started, but then, if he knows his business at all, we are inside his vision and we experience the story, not the telling of it. These three men are masters of this accepted method, although, as I have said, Jones exceeds the careful bounds of its requirements.

Thus, in a journalist’s shorthand version of its own assumptions and vocabularies, a reviewer can attempt to tell what a novel is like by saying who is in it, where they are, what they do, and which of their acts are good and which bad, almost as if we were talking about real people. Gore Vidal’s Washington, D.C. is about “American imperial politics,” about the inner workings of our government, especially in the Senate, from New Deal days to Eisenhower’s advent. Senator Burden Day, a conservative old-school border-state Democrat, sinks Roosevelt’s Court-packing scheme, aspires to the Presidency, misses the boat, and his career declines. As he goes down, his young assistant, Clay Overbury, a poor boy on the make, goes up, and in the end, after much chicanery, takes over the old man’s Senate seat, and seems to be on the way to the Presidency in 1960. Burden Day loses his wife to her dottinness, his mistress to his own stroke, his daughter (temporarily) to a crude one-legged Communist journalist; and because of his one slip from probity, made when he needed money for his Presidential campaign, and because of the young Clay’s treacherous ambition, he loses his public honor. Clay, on the other hand, is a successful satyr; gains a rich newspaper publisher kingmaker’s daughter; betrays her to gain the publisher; with the publisher, railroads her into an insane asylum to avoid the scandal of divorce; gets a stylish wife; and then takes on one girl after another as his status increases. The publisher’s son becomes a dissenting journalist, and it is his morality largely we are expected to share. He marries Senator Burden Day’s daughter in the end. As this systematic story, the plot, unfolds itself, there are scenes in famous places, complications with famous people and with famous types, like liberal journalists and intellectuals who gladly become servants of power, with political hostesses, lobbyists, columnists.

Except for the publisher’s son and the Senator’s daughter, none of these people care for anything but their personal rank. An invitation to the publisher’s great house is a matter of as much concern as a nomination for the Vice Presidency, and is given or denied on much the same grounds of personal prestige and reciprocal favors. The very highest levels of government, then, seem to work much like any petty human group. What its members want is not power, power to do things. They want more badges and feathers than the next fellow. The Depression, even the coming of the Second World War, interests them only as these cataclysms affect their personal positions. To hold their positions, these men must show an honest and appealing face to the public. But in private each of them has a shameful secret, a bribe, homosexuality, a lie, that may destroy them if it becomes known. Politics is a matter of manipulation, jockeying, and public relations. Once there was the old country ham style of Senator Burden Day; now there is the new TV and mass-media style of Clay Overbury. Peter, the publisher’s son, has to oppose this. At the end of the book he is speaking with Aeneas, the radical intellectual who has sold out to ghost-write a book for Clay Overbury. Peter attacks Clay Overbury, and Aeneas responds.

Advertisement

“But he’s not so empty. And he’s certainly far more liberal than you give him credit for, and with the help of people like us….”

“Oh, Christ, Aeneas, you are a fool!” Peter had not meant to roar but he was very much his father’s son, filled with that magnate’s passion to impose his will upon others. But where his father had chosen a conventional path to familiar heights, Peter had tried to go down to the roots, hoping to find the source of his own discontent with a world altogether too eager to take him in and give him whatever he might in the usual way want. Yet he knew that what he really wanted was simply to know what was good, and since he could accept no absolutes he could do little more than resist what appeared to him to be altogether bad, aware that the moment he ceased to say “no,” he would sink like Aeneas to Clay’s level, which was: does it work or not, does one rise or fall?

Politics as character: to know what is good, to resist the altogether bad, which is lack of character. Perhaps that is as far as the novelist’s mixture of history, psychology, and morality can go. Systems do not matter, there are no great men, no great causes. The apes rule and the monkeys who suffer for it are far away. Psychology: Peter is like his father. History: the future President has seduced the intellectuals. Morality: we must resist what we see is bad. In such small essays as these, appended to action and dialogue, we receive the novelist’s vision. The language is sober, familiar in its range, in itself making no appeal to the reader’s feelings. Its only rhetoric is in the everyday metaphors of height and depth, with their everyday meaning. It is easy to read, easy to understand. The novel is intelligent, seems to be very knowing about social facts of Washington both public, and hidden, as indeed it should be, given Vidal’s familiarity with the scene, and yet it is flat, as flat as it says the scene itself is. When the secrets are out, they don’t amount to so very much. Perhaps this kind of politics, these politicians, really aren’t any more interesting or important than Vidal says they are.

PHILLIP ROTH’S When She Was Good is a strange book disguised as a conventional one. It tells the story of the family of Willard Carroll during the first fifty years of this century, in a small town in the northern Midwest of America. Willard escapes the savagery of his father’s forest cabin near the Canadian border, wanting only to be civilized, to live in a house in a town. He succeeds, in Liberty Center—“Oh sweet name. At least for him, for he was indeed free at last of that terrible tyranny of cruel men and cruel nature.” He attains his modest security as assistant postmaster, has a daughter who marries an unemployable weakling; these two, Myra and Whitey, live with Willard and his wife. They have a golden child, Lucy. During the Depression, Whitey takes to drink at Earl’s Dugout and Lucy, a girl of fifteen, has him jailed. He is no father, Willard is no father, her mother is abused and she is shamed by them. Lucy’s dream, like Willard’s, is to get away, to be civilized. She is able to attend Fort Kean College for Women, but then, pregnant by Roy Bassart, she has to marry him. Roy is as feckless as her father Whitey, they struggle for years in small-town poverty; Lucy torments him into leaving with the child, chases them home to Liberty Center, and in a paranoid rage stumbles off to die in a blizzard. The story ends as Whitey, her father, arrives home from Florida, where he has been in jail.

It is hard to tell how representative Lucy is meant to be. Certainly the portrait of her that emerges from Roth’s narrative is convincing, even shocking. Her modest dreams of a quiet, respectable life are mocked or shattered time after time by the men she has to depend on, by her father, her priest, her teachers, her husband. They exploit her and bully her in the cowardly day-by-day meanness of this claustrophobic small town. Roth is both precise and dramatic as poor Lucy’s mind extends her sense of deprivation from the pain of her father’s inadequacy to her shame over her position in her little part of the society of the little town. To Lucy’s family, a high school teacher is someone who can consider himself “high and mighty,” and a friend who owns a cashmere sweater seems a princess. Anyone who has known this life will recognize Lucy, and will acknowledge the accuracy of her speech, her looks, and the ugly likelihood of her fate as she is driven into hysterical bitchery and madness by the world she lives in.

Advertisement

She is no Carol Kennicott, trying to bring enlightenment and “sophistication” to her Main Street. Lucy would gladly settle for Liberty Center’s own ideals, if she could only find someone who would let her live by them. But there, it seems to me, lies the puzzle. Is it Liberty Center itself, town of the common man in the common heartland of America, that is at fault, or is it those who have gone weak there, those who fail even Liberty Center, who doom this girl? No doubt of it, the Midwest is cruel. Those who survive there longer than Lucy do so by wearing blinders, by brainwashing themselves, and by having a little more luck and a little more money than she was granted. It seems to be the author’s tribute to her that she does not lose the energy to protest. But since she has nothing to push against except the wet noodle of her husband Roy, this American boy next door, she is lost. Of course the author doesn’t have to be making a general statement about America, about its small towns or its young women of our time. Lucy herself is real, painfully, hopelessly real; but her very individuality, her particular circumstances, seem to deny her the stature of Mrs. Kennicott or Mme. Bovary.

Her story is recited with very precise sophistication, in scene and exposition and dialogue, all absolutely locked in on this family and their relatives and acquaintances: told not exactly in their language, but in a knowing, clever prose that is always modulated with their lower-middle-class dialect.

She still thought he was a little coarse with his language, but she didn’t object, corny though it was, when he called her “Blondie,” which seemed to have become his nickname for her, or even when he put his arm around her waist one evening and said (in a joshing way of course, and winking at Roy), “You just tell me, Blondie, when you get tired of looking up at this big lug and want to look down at a little one.”

All this has the sadness and the authenticity of a small-town graveyard. The simple effort to make a simple life can be tragic. Simple small-town people, who are nicknamed “Blondie” and who think this “corny,” can go mad with despair. They aspire only to Fort Kean College for Women, and for a family; but are their vocabularies too vulgar even for this? Is it inadequate perhaps even to aspire to a family, to be American, to live in a small town? Why is the author so meticulously absent? Scarcely does he even mock them, as Sinclair Lewis used to do; he does not seem to wish them well, as Sherwood Anderson did, nor to connect them with human fate, as Peter Taylor does. Only once is he really savage, and this is exactly about the inadequacy of their vocabularies, of the vocabulary in which the story is so subtly told, and this is when Whitey writes from jail to Lucy’s mother the letter Lucy dies clutching to her cheek. In his outburst of self-pity and misery he can only say.

At least the great wish that would

be really mine,

That I could just once more—be

your Valentine.

One can only wonder why the author, from whatever height he has concealed himself upon, has watched these people with a gaze so long and pitiless and blank.

MOST OF THE PEOPLE in James Jones’s Go to the Widow-Maker belong to a new and nameless class that has not been much noticed in books. They are proletarians who have become rich since the war, but they have not changed their tastes nor their manners nor their speech. They travel now, they own boats or planes, they have money to invest, and in their new leisure they go in for new sports like custom-car drag racing and skin diving, sports that have the dangers of the old sports like big-game hunting but have none of the traditions. They speak the dialect that nearly every man who has grown up in America knows, and often speaks to other men, a dialect seldom used more than briefly in writing. It expresses a peculiar attitude of masculine aggression and sexuality and solidarity, largely through its obsessive obscenity. Jones uses it to explore the complexities of this attitude, of its ability to get into its speech contradictions of rivalry and affection, Oedipal passion, homosexuality, and its many contrary concerns about women.

His story has many characters. His hero is Ron Grant, from the Midwest, a war veteran, thirty-six years old, a playwright tremendously successful on Broadway. It seems to have embarrassed some critics that his hero closely resembles the author himself, perhaps because, like the author, the hero is much praised from time to time, and has admirable qualities. Other recognizable persons are present also, but does that matter? The important characters are made real in the book, although it is true that some characters, some episodes, seem to be included only because they happened and these, whether they happened or not, seem unreal.

Grant is in the midst of a love affair with a beautiful New York party girl, and this threatens to break up his long allegiance to his aging mistress and mentor, Carol Abernathy. As a sort of test of himself, he undertakes to learn the difficult and dangerous sport of deep undersea diving. He goes to the island of Jamaica and hires an instructor, Al Bonham. Grant is capable physically, but Bonham is a giant. Grant is timid about diving and knows it; Bonham is absolutely unafraid of the sea, he attacks sharks single-handed for fun. Grant much admires Bonham, and Bonham finds Grant an admirable and profitable pupil. Grant admires his teacher also for his capacities in food and drink and sex, and for his wish to lead an independent life of adventure outside the ruled limits of society. Throughout the book, Grant struggles to find his way in the conflicts over his new girl, his own impulses of jealousy, his old mistress and her fatherly husband, and the world of the masculine as presented by Bonham and his associates. In the end, he wins out, and Grant and Lucky have agreed to walk together a dangerous tightrope on which one misstep—one “stepping out” as it is put in the old-fashioned Midwestern dialect—will mean disaster.

IN TELLING THIS STORY, Jones has all his famous difficulties with English syntax. Still, although the most interesting things are not those he presents in his version of standard English, but rather in his vernacular of obscenity, he can do quite brilliant set pieces when they are called for. His descriptions of the sea, of diving recall and sometimes surpass in their figures and their visual imagery those of Lawrence Durrell, for instance. In Durrell’s Clea (page 226), and in Go to the Widow-Maker (page 16), there are presentations of diving into undersea grottoes paralleling each other in many ways, as I suppose these experiences do. They are too long to quote here, but as I read them, Jones’s is at least as evocative and vivid as Durrell’s, and ends more daringly, and more soundly in connection with the rest of its story. Alone in this vast gallery beneath the waves, breathing from his acqualung as he rests and looks around, Jones’s hero is seized with an overwhelming desire to masturbate. Honi soit qui mal y pense.

In this scene, as in many others, Jones’s language is quite conventional, given a little slippage in pronouns and in the agreement of complex nouns and subjects. But his use of the proletarian dialect of obscenity allows him an entirely new accuracy of fact and of valuation in speaking of sexual experience. No other writer has ever done this so well. It is more than a matter of using obscenities, as we call them; it is a profound honesty, a willingness to connect physical experience with feeling that neither pornographers nor those who speak only of the feelings and obscure the physical can hope to manage. As he manages this about sex, so he does about aggression. Jones uses the language of masculine aggression, knows how to assess its undertones of sexuality, and in the action he presents, he shows the consequences of these feelings. Those who imagine he is simply praising the male world do not understand him at all.

Go to the Widow-Maker is frequently so unabashed as to sound, to an unwilling ear, not unabashed but foolish. To be honest with his reader, the author has to present without irony as successes those things that he honestly finds to have been successful. This is a very risky enterprise, easy to mock. Failure is ingratiating, there is a lot about success that makes the rest of us dislike hearing of it. In this book there are, as I have said, too many episodes, too many things that only happened. We are given too many dives, too many fights, too many voyages, too many dialogues that appear to the author to have had intellectual content but which to the reader are only boozy vaporings. Still, success is difficult and who can tell what may have contributed to it? So he puts it all in. The course of failure is easier to chart.

Jones’s novel has superficially the form of a fat conventional novel, and so clumsy is it, so weighty, so persistent—he says of the writing of his hero, “He didn’t spend much time in stylistic niceties but just sort of bullassed right through”—it may seem to some readers a mere exploitation of the form. But I think they are wrong, and to many people it will be a very important book. It should make many previously accepted conventions quite impossible now; but more than that it offers a new kind of history, a profund psychology, and above all a morality that is full of possibilities.

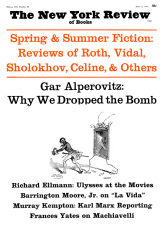

This Issue

June 15, 1967