To the Editors:

The trial and imprisonment of two Russian writers a year ago in the Soviet Union was met by an uproar from our uncensored intellectuals. Widespread protests were heard against the sentencing of Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel for having published “anti-Soviet” satire, after smuggling it abroad.

Yet it is a striking oddity to me that these same defenders of the freedom to write in the Soviet Union are now silent on the criminal censorship imposed recently on hundreds of writers in Greece, where the freedom and the profundity of thought first bloomed.

Aeschylus and Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes (men who have been appreciated longer than Sinyavsky and Daniel) have been blamed by the military junta and they would have been imprisoned had they been alive. Anyway, the modern poets Yannis Ritsos and Tassos Vournas, both past sixty and both suffering from tuberculosis, are now behind bars. So is the popular octogenarian Kostas Varnalis, and Mrs. Vaso Katraki, whose etchings won for Greece the first prize in last year’s Venice Biennale. Moreover, the work and promise of hundreds of others, who merely may oppose the military regime, has been stifled. There is subversion for the colonel even in the music of Theodorakis, Tchaikowsky, and Prokofiev, as in the works of Mayakovsky, Kazantzakis, and Nina Potapova. To top it all, dozens of literary magazines have been closed, their editors jailed.

Where then are the shouts now against these atrocities in the mother of Western Culture? Are our critics and writers forgetting their legacy, their debt to Greece? Is the spirit of Byron dead? Or is it that in the eyes of these responsible intellectuals, censorship and injustice becomes visible only when the victims are politically and conveniently interesting?

Minas Savvas

Department of English

University of California

Santa Barbara

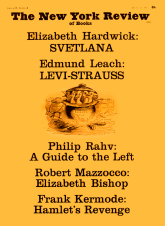

This Issue

October 12, 1967