Cast your mind back half a century ago, if you can, and try to recapture the mood—a mixture of bewilderment and exaltation—stirred in millions of people all over the world by the news from Petrograd (soon to be called Leningrad) in the late autumn of 1917. Then try to imagine the enthusiasm which the fall of the Bastille in 1789 evoked in an earlier generation of bystanders soon to be appalled by news of the Terror. If you are historically minded, compare the Jacobin record with that of the Bolsheviks. Note the differences: the Jacobins were a club, the Bolsheviks a disciplined and centralized party. Note too the similarities (in outlook and temper, if not in doctrine). Bear in mind that Lenin’s predecessors among the Russian radicals of the 1870s were proud to style themselves “Jacobins.” Recall that this nomenclature had been rendered plausible by the resemblance which the last of the Romanovs bore to the least fortunate of the Bourbons. The fall of the autocracy in March 1917 (February according to the old Russian calendar) closely paralleled the demise of the ancien régime in 1789). But in France it took three years before liberalism and constitutionalism yielded to civil war and dictatorship. In Russia the corresponding historical space was traversed in eight months. Moreover, the Bolsheviks, unlike the Jacobins, retained power (and wrote the history books). There was violence and terror in plenty, and for three dreadful decades the rule of a savage despot; but no restoration.

Or try another approach. Stalin was Lenin’s successor, and Lenin prided himself on being a Marxist. But everyone (even in his own party) knew that his Marxism was unorthodox. In the 1920s, when such candor was still barely permitted, a few Soviet historians even possessed the temerity to suggest that Lenin had, as it were, synthesized Marx and Bakunin. Others, especially among the exiled Mensheviks, recalled the links between Lenin’s faction and the Narodovoltsy of the 1870s and 1880s who preceded Marxism. But then the Marxists did not have an altogether unambiguous record on the issue of dictatorship. Their grand old man, Plekhanov, in 1903 delighted the future Bolsheviks at the famous Second Party Congress by exclaiming salus revolutionis suprema lex! Not a very democratic utterance, though perhaps understandable in the circumstances. At any rate Lenin on this occasion was very pleased with Plekhanov and went so far as to call him a “true Jacobin”: the highest praise he could think of. In 1917-1918 Plekhanov, by now a democrat and even a “social-patriot,” denounced the Bolshevik seizure of power as madness, and was in turn excommunicated from the newly founded Communist movement.

By then Menshevism had reorganized itself under the leadership of Martov, who until the end of 1920 kept a “loyal opposition” going in Moscow: loyal to the Soviet regime in the civil war, but disloyal from the Bolshevik standpoint, since Martov insisted upon a speedy return to democracy and would have nothing to do with terrorism or the one-party regime. In the end his paper was suppressed and he himself obliged to emigrate. Yet he and Lenin were old and close friends. They had jointly helped to found the illegal Social-Democratic movement in 1895, and been arrested and sent to Siberia together. When Lenin lay dying in 1923, his thoughts went back to his old companion, now driven abroad by the Bolshevik regime and slowly succumbing to tuberculosis. “They say that Martov too is dying,” he said (according to Krupskaya). Later, already speechless and paralyzed, he would silently point at Martov’s writings on his shelves. Meanwhile the Politburo sat for hours debating means of getting money for medical aid through to the mortally stricken Martov in Berlin. (“He won’t accept it from you,” Ryazanov told Lenin.) This was during the grim winter of 1922-23, when hundreds of thousands in Russia were dying of cold and starvation. Yet when the matter was raised (at Lenin’s insistence) in the Politburo, no one objected—not even Stalin.

What held these men together? A common faith? The memory of past comradeship? The unspoken creed of the radical intelligentsia—that fraternity of chosen spirits which one entered by way of imprisonment and from which one could exile oneself only by death or betrayal? But what did “betrayal” mean if it did not signify going over to the obvious enemy, the Tsarist autocracy? After 1917 most of the former Mensheviks were “enemies of the ‘October revolution,’ ” but how could Martov ever be thought a “traitor”? (It was different with those right-wing Mensheviks in Georgia who in 1917 collaborated with Kerensky, and later with the “Whites” or the Entente.) Martov was a heretic—and to the end Lenin went on hoping that he would see the light (as after all, Trotsky, another one-time Menshevik, had done). But Martov would not oblige, though he stayed on in Moscow all through the civil war, called upon the workers to defend the Soviet regime against the White armies, and relentlessly expelled any member of his own faction who refused to follow his line.

Advertisement

MARTOV was a democrat; he loathed terrorism; he did not believe Bolshevik dictatorship was either necessary or legitimate, and he invariably used every opportunity to denounce Lenin and Trotsky in public, while still urging the workers to save the remnants of democracy they owed to the revolution. In June 1918, with the civil war already in full swing, the Bolshevik majority expelled Martov and his few remaining associates from the Soviet “parliament”: the All-Union Central Executive Committee of Soviets, in theory the highest governing body. A furious scene followed. In his authoritative and very readable biography of Martov, Mr. Getzler cites a Bolshevik eyewitness:

Martov, swearing at the “dictators,” “Bonapartists,” “usurpers,” and “grabbers,” in his sick, tubercular voice, grabbed his coat and tried to put it on, but his shaking hands could not get into the sleeves. Lenin, white as chalk, stood and looked at Martov. A Left S. R. [Social-Revolutionaries: then in temporary alliance with the Bolsheviks], pointing his finger at Martov, burst into laughter. Martov turned around to him and said: “Young man, you have no reason to be happy. Within three months you will follow us.” His hands trembling, Martov opened the door and left.

On this occasion at least his prophetic instinct had not deserted him. The Social-Revolutionaries broke with Lenin a month later (on the issue of armed resistance to the Germans in occupied territory) and for a change employed terrorist tactics against their former Bolshevik allies. Martov would have none of that either. He stood for peace and freedom, and for a civilized sort of democratic socialism. Utopian in the Russia of those days? No doubt, but then whose fault was it that the country had been plunged into civil war? Martov held Lenin responsible. They had been opponents since the fatal split of 1903 which Lenin had forced upon the nascent Social-Democratic movement. Now “Bolshevism” (in its origins a purely factional term) assumed a new and sinister significance: Lenin, in Martov’s eyes, had become the exponent of a deliberate return to the most primitive aspects of Russia’s past system of government:

War en permanence not only feeds Bolshevik terror and the international halo of Bolshevism; but also Bolshevism itself as a monstrous economic system and an equally monstrous system of Asiatic government. Bolshevism is therefore vitally interested that war should be permanent and unconsciously shies away when confronted with the possibility of peace.

That was Martov’s considered judgment in 1920, when his former friend and ally, Leon Trotsky, stood at the head of the Red Army. Since 1903 they had jointly opposed Lenin, until Trotsky went over to him in the summer of 1917. Now Trotsky was co-responsible for the “monstrous system of Asiatic government,” but ten years later he himself would be expelled from the Party, and then driven into exile, there to resume the theme of Martov’s furious imprecations against Lenin; the only difference being that in the meantime Lenin’s place had been taken by Stalin, for whose savagery no parallel could be found even in the excesses of the Terror during the civil war of 1918-21.

IS THERE SOME LOGIC in all this? Prima facie it does not seem surprising that men like Martov and Trotsky should have found it impossible to stay the course. Trotsky was a great deal tougher than Martov (as indeed he proved when he defended the Terror and smashed the Kronstadt rebellion in 1921), but in the end they had something in common: both were Jewish intellectuals, the flower of a generation which had abandoned the ancestral faith, drunk deep from the well of Russian literature, and yet conserved some inherited sensibilities of temper and outlook which caused them to shudder at the barbarities of Stalin.

Mr. Getzler, whose researches into Martov’s background are illuminating, makes a good deal of his personal antecedents and his early association with a purely Jewish labor movement in Vilna: the Bund. He also brings out a circumstance usually overlooked by writers unfamiliar with the political landscape of the 1890s: the fact that the Bund, having been founded a few years before the Russian movement (properly so described) got under way, became the training school of a whole generation of early Marxists, most of whom, after the split, chose the Menshevik side.

MARTOV himself eventually repudiated the idea of a separate Jewish socialist movement; others stuck to it, but continued to cooperate with the Menshevik faction of the “Russian” party. Does all this mean that the Bolshevik wing was the more “national” of the two? It was certainly closer to the masses of recently uprooted peasants then streaming into the cities. Both Mr. Getzler’s biography of Martov and Mrs. Vera Broido’s recently published edition of her mother’s autobiography (an abridged Russian version of which was legally printed in Moscow in 1928) make it clear that on the eve of 1914—that is, before the outbreak of war—Bolshevism was gaining ground among the workers in Petersburg and Moscow. Indeed it would seem that by 1914 the Mensheviks, representing the “reformist” wing of the Social-Democratic movement, were already losing the fight so far as the working masses in the two capital cities and the other industrial centers were concerned. Most of the newly constituted factory proletariat, “romantic, primitive and rebellious,” responded favorably to the “primitive” slogans of the local Bolshevik leadership:

Advertisement

…a handful of people literally without names or with names that had an unsavoury ring, a group which belonged rather to the intellectual Lumpenproletariat than to the intelligentsia. Having taken the baton into their hands, they turned corporals, carrying the name of one intellectual—Lenin—as their ideological banner….this means that in the Bolshevik section of the proletariat there was a demand for such a baton and for such corporals.

But if this was Martov’s judgment in 1914, when Russia was at peace and had just acquired an elected parliament and other quasi-liberal institutions (including a free press), was it really so surprising that he and his colleagues were unable to ride the storm in 1917, when the war-weary cities were hungry, the monarchy had fallen, and ten million peasant-soldiers were clamoring to come home and seize the land from the landlords? Against Martov’s complaints about Bolshevik barbarism in 1917, there must be set the judgment of a Western social-democratic author who has never shown the slightest sympathy for the Soviet regime and all its works: “Lenin alone understood the mood of the revolting soldiers and peasants.” (Cf., W. Klatt, “Fifty Years of Soviet Agriculture,” Survey, London, October 1967.)

The reader in search of a portrayal of the men and women who prepared the ground for the upheaval of 1917 must saturate himself in Mrs. Vera Broido’s admirably translated and edited memoirs of her mother, one of the pioneers of that intelligentsia from which the minority faction of Russian Social Democracy was in due course to arise. The failure of Menshevism was the failure of a thin stratum of Europeanized intellectuals (mainly Jews from comfortable “assimilated” families), plus a not much wider layer of Russian workers who were proud of their unions and had acquired the civilized values of European Social-Democracy: the famous “labor aristocracy” against which Lenin in 1917 mobilized the masses of the proletariat and the peasantry. There was a fleeting moment in the summer of 1917—before the mountebank Kerensky had plunged the army and the country into disaster by launching a crazy military offensive against Germany—when the democratic parties could have pulled Russia out of the war and satisfied the land-hunger of the peasants. Once this opportunity had been missed, the choice lay between Bolshevism and a military dictatorship of the Right. This constellation determined the civil war years of 1918 to 1921. It also determined Martov’s despairing resolve to stay at his post—and Trotsky’s adventurous decision to take the headlong plunge into dictatorship and terrorism. The one man who never doubted or faltered was Lenin. From start to finish he, and he alone, knew what he wanted and was ready to pay the price. But then he was the heir of the Narodnaya Volya and its terrorists, as much as he was the disciple of Plekhanov and the “Emancipation of Labor” group who had been proud to style themselves Marxists. It was this unique combination which made Bolshevism possible. It has also proved to be its organic limit.

NOT A GREAT DEAL of light is cast upon this fateful theme by the late Isaac Deutscher’s Cambridge lectures, delivered in January-March 1967, a few months before his sudden death. These lectures (now assembled under the title The Unfinished Revolution) display the familiar characteristics of their author: solid learning, an impressive command of the English language, and an unflagging devotion to the cult of Lenin. Deutscher’s work indeed is proof that one can swallow Lenin without renouncing the spiritual heritage of Rosa Luxemburg and Trotsky. This is not really so surprising, for had it been otherwise, the Polish Communist party (of which he was a member until 1932) could not have come into being. The trouble is that if one wants to hold on to this particular tradition, one has to stay within the conceptual world of Eastern Europe: more precisely, of Leninist communism, as it existed until 1939 or thereabouts. For in those years it was still possible to believe that the Soviet regime might one day be democratized and brought back to its primitive origins. These hopes, if not precisely dead, have today acquired a connotation very different from the one they possessed during the interwar period when Jewish intellectuals in Warsaw were busy arguing the respective merits of Communism, Zionism, or Bundism. There is one country in the world where a political movement shaped in this image still has a place: Israel. Paradoxically, considering his dislike of Zionism and his readiness to echo the conventional Communist line on the subject, Deutscher had (and perhaps still has) a more numerous following in Israel than in his native Poland, where his writings are difficult to obtain. For his particular kind of romanticism, a Jewish intelligentsia by itself was not enough: one also needed a Jewish proletariat. Once Stalin had liquidated the former, and Hitler the latter, the spiritual world of Isaac Deutscher had vanished from the map of Eastern Europe. Hence his work, for all its undoubted literary merits, has become a monument to a myth.

The myth is that of the revolution which “went wrong.” To the question, why did it go wrong, his answer is: because there was no world revolution. Russia remained isolated and Lenin’s successors thus had to make the best of unforeseen circumstances. Their political and doctrinal conflicts were forced upon them by the failure of the original movement to spread further west, and in the end Stalin took the plunge into autarchy, with all that it entailed in suffering and horror:

…in the middle 1920s, the fact of Russia’s isolation in the world struck home with a vengeance, and Stalin and Bukharin came forward to expound Socialism in One Country. The Bolsheviks had to take cognizance of the bitter necessity for Russia to “go it alone” for as long as she had to—that was the rational kernel in the new doctrine which captivated many good internationalists; and with it neither Trotsky nor Zinoviev nor Kamenev had any quarrel [p. 67].

This places rather too much weight upon the disputes among Lenin’s followers. Their master after all had left them a Testament—not the celebrated letter usually mentioned in this context, but his final public pronouncement: the essay bearing the title “Better fewer, but better,” which appeared in Pravda a few days before the stroke that incapacitated him. In this programmatic piece of writing, Lenin outlined the situation with his customary unflinching logic. On the one hand, the revolution in the West had been temporarily stalemated. “On the other hand, precisely as a result of the first imperialist war, the East has been definitely drawn into the revolutionary movement, has been definitely drawn into the general maelstrom of the world revolutionary movement.” When one took into account the inter-imperialist rivalries, the world balance was not unfavorable,

because in the long run capitalism itself is educating and training the vast majority of the population of the globe for the struggle. In the last analysis, the outcome of the struggle will be determined by the fact that Russia, India, China, etc., account for the overwhelming majority of the population of the globe…. In this sense the complete victory of socialism is fully and absolutely assured.

But what was to be done in the meantime? “To ensure our existence until the next military conflict between the counter-revolutionary imperialist West and the revolutionary and nationalist East, between the most civilized countries of the world and the Orientally backward countries—which, however, comprise the majority—this majority must become civilized. We, too, lack enough civilization to enable us to pass straight on to socialism, although we do have the political requisites for it.” Various practical proposals follow for making sure that industrialization should get under way. “In this, and in this alone, lies our hope” (Collected Works, vol. 33, pp. 500-501).

Thus Lenin in 1923, on the very last occasion when he was able to communicate his thoughts to the party. The article—one of the most important and influential ever to come from his pen—appeared in Pravda on March 4, 1923, exactly thirty years before Stalin’s death. During those thirty years, Stalin was carrying out the instructions of his leader and teacher. It really is time, after all the nonsense that has lately been written on this subject, to set the record straight: Stalin was a savage brute and toward the end a half-mad despot. He was also a good Bolshevik—a better one than Trotsky, who never quite got over his understandable longing for a socialist revolution in the West which would restore the universality of the movement (and incidentally make it unnecessary for the USSR to raise itself by its own bootstraps). Hence all that desperate scurrying around for a revolution abroad: in Germany, in France, in Spain—in Bulgaria if necessary. Anything to get rid of the awful sense of isolation that gripped the Bolsheviks from the mid-Twenties onward. Stalin had the sense to realize that all this frantic stuff was no substitute for a “military-industrial complex” big enough to stand the test of war. As he put it in 1931: “We are fifty or a hundred years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in ten years. Either we do it or they crush us.” How right he was! Exactly ten years later with Hitler’s attack in 1941, the test came and the USSR (largely owing to Stalin’s own insanities) very nearly failed it.

THESE REFLECTIONS are not to be found in Isaac Deutscher’s eloquent little tract, but then its author was not a real Bolshevik (any more than his hero, Trotsky, was). Stalin was—with all that it implied. He was prepared to let millions die of starvation, and ship other millions off to labor camps, if Plan fulfillment demanded it. In the very year when he told an assembly of industrial managers they had one decade to get ready, he “collected” and sold abroad five million tons of grain to pay for machine imports. Those five million tons (extracted from a hungry peasantry at the point of the gun) cost the lives of five million people who did not survive the great famine of 1932. That was what “Socialism in One Country” meant in practice. Necessary? Of course it was, once the Bolsheviks had landed themselves in the sort of mess they were in when Lenin died! Was it worth it? Might it not have been better to let the industrialization of Russia go forward under bourgeois auspices (if the bourgeoisie was capable of it)? The question is meaningless. Once Lenin had taken the plunge in 1917, all the rest followed. The most one can say is that under his leadership the pace in the 1930s would probably have been somewhat less frenzied, and the crowning horror of the Great Purge in 1937-38 would certainly have been avoided. For the Purge was Stalin’s personal contribution, just as the “Final Solution” was Hitler’s. In the short, if not in the long run, individuals do make a difference.

Some of these topics, and a large number of others, are analyzed, with great care and scholarly exactitude, in the learned volume put out by the Royal Institute of International Affairs under the title, The Impact of the Russian Revolution 1917-1967. The contributors—Professors Arnold Toynbee, Peter Wiles, Hugh Seton-Watson, Richard Lowenthal, and an Australian scholar who lives in Paris, Neil McInnes—cover more ground than can possibly be indicated even in the briefest and most synoptic fashion. It must be sufficient to say that the volume lives up to the expectations aroused by such an assemblage of talent; it should be a godsend to students in search of reliable information about Soviet Politics and economics. The same can be said of Julius Braunthal’s History of the International 1864-1914, the work of a distinguished social historian who is himself a veteran of the great age of Austro-Marxism and has been personally acquainted with most of the leading figures of European Social-Democracy over the past half century. His introductory chapter on the Communist League of 1848 and its antecedents supplies a link between his account of the First and Second Internationals (1864-1914) and the storm that broke over the Socialist movement thereafter; for in it he brings out the underground filiation running from the extreme wing of the French Revolution, via the Communist Manifesto of 1848 to the Communism of Lenin’s day—a topic also discussed at some length by Richard Lowenthal in his interesting essay in the Chatham House volume.

MARX, who in 1848 launched the Manifesto upon a far from startled world (the air then was full of revolutionary utterances, though lacking the sweep of Marx’s analysis) lived for another thirty-five years and did most of his real work after he had broken with his old Communist associates. In 1864, while settled comfortably in Hampstead—it is a myth that he always lived in poverty—he sat down and composed the statutes of the First International, an organization so moderate and democratic that the British trade unions for eight years helped to keep it going. What was later called “democratic socialism” received its birth certificate from the author of the Manifesto (then at work on Capital). Was Marx then an ex-Communist? Had he and Engels by 1864 become Social-Democrats? Well, yes and no. They had acquired some faith in the democratic process by way of England (and America). For France and Germany they were less sure that it would work. As to Russia they had no doubt at all: the Russians would have to take up the burden which the French had dropped. This indeed was accepted by all Russian Marxists, including the Mensheviks: Martov’s writings, for example, contain endless references to the French Revolution and its hoped-for and longed-for Russian successor.

BUT WOULD the coming Russian revolution be a socialist one, or would it limit itself to turning the country into a democracy? This was where the uncertainty began. Even Lenin changed his mind on this crucial subject. As late as 1905 he stood for radical democracy, welcomed the introduction of capitalism (“European, not Asiatic”), and dismissed all talk of a socialist revolution in backward Russia as anarchist nonsense. Even in 1917 his party still clung to this line and, but for his timely arrival in Petersburg, would unquestionably have stuck to it. In that case Russia in all probability would—after an interval of military rule—have become a democracy in the Western sense of the term. Well, not quite Western perhaps, but near enough. After all, the democratic parties won a huge majority in the only completely free election Russia has ever had: the one in December 1917. Even though the windbag Kerensky had spoiled the chances of democracy in that year, these parties—but for Lenin’s fateful intervention—might have got their second wind after the Right had failed. For there would no doubt have been a period of military rule, if only because the Army could not reconcile itself to the threatened advent of democracy. But how long would it have lasted? On balance it seems likely that Russia would in the end have got its “French Revolution” under democratic auspices. The land hunger of the peasants would have supplied the necessary driving force. Then Stalinism would not have been the “historical necessity” it did become after Lenin had foreclosed all other options.

Be that as it may, the Soviet Union is now the world’s second industrial and military power. It has also acquired universal semi-literacy, mass-production of shoddy consumer goods, motor cars for the elite, television, and the other appurtenances of the good life. In another ten or fifteen years it may even be ready for the message of behaviorism, or McLuhanism, or some other kind of fashionable foolishness. In all probability these results could have been secured at a less extravagant cost and without an interlude of utopianism finally drowned in the Stalinist bloodbath of 1937-38. But that is the way history operates—especially in Russia. Other countries have their own manner of solving, or failing to solve, their problems. For most of them the Bolshevik model is unsuitable. Even Latin America is unlikely to copy it (indeed Castro has virtually said so).

What of the other strand in the socialist tradition—the one that got its theoretical underpinning from the Marx of Capital and the First International? The centenary of that highly respectable organization’s founding fell in 1964, when—by an agreeable coincidence—the British Labour Party won an election and Harold Wilson became Prime Minister, thus adding his name to that of a lengthening list of Social-Democratic dignitaries in countries such as Holland, Sweden, Denmark, and Norway. Let no one protest that this juxtaposition is unfair. It is undoubtedly striking. From Stalin to Wilson—du terrible au somnolent. But if Wilson puts one to sleep, is this not better than being taken out and shot? The British at any rate think so (including, if the truth be told, most members of the British Communist party).

When all is said and done, the fact remains that Marx did lend his authority to the democratic tradition, which is why his grave in Highgate cemetery is carefully tended by the local authority. For Communists there is the consoling thought that the second congress of the Communist League met in London in November 1847, with Marx in attendance (it was then that he was commissioned to write the Manifesto). London can thus lay claim to the rank of a holy city of the faith, and although currently governed by a Conservative municipality, it has manifested its own brand of devotion: A Marx memorial exhibition was opened at the British Museum last September to commemorate the centenary of Das Kapital, and at the same time a plaque was solemnly affixed to the house in Dean Street, Soho, where its author lived for seven miserable years from 1849 to 1856. The ceremony was attended by a Conservative municipal councillor (a lady dressed in Tory blue) and was reported at length in all the papers, from the Communist Morning Star (circulation 60,000), via the London Times and the Guardian, to the Daily Mirror (circulation six million). If this proves nothing else, it shows at least that Marx has become respectable.

IS IT FRIVOLOUS to draw such comparisons? Not if one realizes that Communism in the West is now slowly reverting to its Social-Democratic origins. The process is furthest advanced, as might be expected, in Scandinavia, where the local Communist parties have now formally renounced the Stalinist inheritance (though not as yet the cult of Lenin). It proceeds a trifle more slowly, but quite steadily, in Britain. It has begun in France and is making rather more rapid headway in Italy. It is still blocked in Spain by the Franco regime, and has recently suffered a setback in Greece. Most remarkable of all, it is under way in Central and Eastern Europe, where the spread of “revisionism” is motivated by the discovery that Bolshevism was, after all, a very Russian affair—not ordained by “historical necessity,” but brought about by a unique constellation of circumstances: the fall of Tsarism and the failure of the democrats to exploit their opportunity, while a revolutionary leader of ruthless genius and titanic will power—Lenin—dragged his reluctant party into an uprising which but for him would never have taken place. Fifty years later even the Communists are coming to understand the uniqueness of this event, and that is the beginning of wisdom.

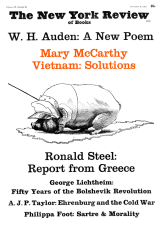

This Issue

November 9, 1967