In response to:

"The Responsibility of Intellectuals": An Exchange from the March 23, 1967 issue

To the Editors:

Every issue of the NYR seems to register a deeper sense of the horror, anger, and frustration felt by a large part of the intellectual community in the face of the Vietnam war. Yet the question that George Steiner put to Noam Chomsky—“What shall we do?”—never has been satisfactorily answered.

Obviously there is no single answer, but one kind of action that I believe should be considered is an organized boycott of government activities. I am thinking particularly of the many programs related to foreign policy in which the State and Defense Departments at present benefit from the knowledge and advice, or even the association with, the scholarly world.

The chief difficulty that arises in justifying such a boycott is that it may entail damage to intrinsically constructive programs. I have tried to deal with that tricky issue in my letter of resignation from a nominating committee for Fulbright awards. A copy of the letter (to Mr. Francis A. Young, Executive Secretary of the Committee on International Exchange of Persons) is printed below. But here I would add one point. In commenting on my resignation, Senator Fulbright asked me, “Do you believe I should resign from the Senate since I too thoroughly disapprove of our government’s policy in Asia? I agree that these are not easy decisions, but I believe we must continue to try to change the policies—“

The answer, of course, is that it would be foolish for the Senator to resign. But whereas he is in a position to have a significant influence upon American foreign policy, most scholars who serve under government auspices are not. In most cases, I think, intellectuals who work for—or with—the government, no matter what their private opinions or, for that matter, the immediate results of their actions, do in effect lend support to the basic national policies of the moment. Besides, no action by an individual would seem to me comparable, in its potential effectiveness, with a concerted refusal on the part of the intellectual community to associate itself with this country’s reckless foreign policy.

Leo Marx

Professor of English and American Studies

Amherst College

Amherst, Massachusetts

September 4

Dear Francis:

I have decided not to attend the forthcoming meeting of the ad hoc nominating committee for Fulbright awards. During and since my recent year of service as a lecturer in France, I have given some thought to the ambiguous relationship between the Fulbright scholar and our government. What troubles me, to be specific, is whether a teacher should serve under the auspices of a government which he believes to be following an increasingly reckless foreign policy.

Of course I recognize the essentially constructive nature of the Fulbright program itself. Because the exchange of scholars between nations contributes to mutual understanding and good will, it no doubt provides a counterweight to militarism. That is the laudable aim of the program. Yet it would be naïve to ignore the other political function of the scholar who lectures abroad under government sponsorship. Everyone regards him, and with some justice, as a semi-official representative of this country, its values and goals. By making his presence possible, and by involving him in its cultural affairs activities, the government of the United States appears to share the peaceful aims of the international community of scholars. He thereby confers upon this government a benignity and dignity which, under present circumstances, I do not think it deserves.

But it would be wrong to pretend that the choice between these two interpretations of the Fulbright scholar’s role is a simple one. Until recently, in fact, I have considered his positive contribution more important than the support he inevitably lends, whatever his personal opinions, to this country’s foreign policy. At this critical time, however, when our leaders seem prepared to annihilate an entire nation and to risk the ultimate war, I believe that American scholars have a duty to bring all possible pressure to bear in favor of a return to a rational and humane foreign policy. For this reason I have decided not to serve on the committee.

In conclusion, let me repeat that I have made this decision in spite of my respect for the Fulbright program itself, and for the way that you and your colleagues have administered it. Having held two lecturing awards, and having served an extended term on the national selection committee, I know something about the hard work, skill and devotion that have made this admirable program a success. I look forward to the time when the aims of our government and those of the scholarly community can once again be reconciled.

I am taking the liberty of sending a copy of this letter to Senator Fulbright.

Leo Marx

September 14

Dear Professor Marx:

Thank you for your letter of September 4, enclosing a copy of your letter of resignation to the ad hoc nomination committee of the International Educational and Cultural Exchange program.

I can certainly understand and sympathize with the views that led you to make this decision. Certainly the American lecturer abroad is in a broad sense a representative of his country. At the same time, I would hope that he would not feel inhibited in expressing constructive criticism of his country’s policies if he were so moved.

Sincerely yours,

J.W. Fulbright

Chairman

Commitee on Foreign Relations

U.S. Senate

Washington, D.C.

I do regret your resignation, because the program benefits from sensitive and perceptive people. Do you believe I should resign from the Senate since I too thoroughly disapprove of our government’s policy in Asia? I agree that these are not easy decisions, but I believe we must continue to try to change the policies.

September 23

Dear Senator Fulbright:

…First, let me say that of course I do not think you should resign. But your position and that of the foreign exchange scholar seem to me to be quite different. You are in a position to change our policies. But my notion is that perhaps—and I am far from sure that I am correct on this score—perhaps the best way for scholars to change our government’s policies is to boycott such programs. My argument is that when we go abroad under government auspices we are lending the dignity and benignity of the scholarly community to government policy.

I would be most interested to know your further thoughts on this subject. To be specific, do you think that a widespread boycott of such government programs by the academic community would serve any useful political purpose—useful, that is, with a view to bringing further pressure upon our government to reconsider its reckless foreign policy?

Leo Marx

October 10

Dear Professor Marx:

I wish to acknowledge your further letter of September 23, asking me to give any additional comments I might have on your argument that a widespread boycott of the exchange program, and similar ventures, by the academic community might serve as a useful political device. I can only reiterate my view that the general subject we are treating is largely a matter for the exercise of one’s own individual conscience. Personally, I doubt whether an academic boycott is either feasible or fruitful. What does seem fairly certain, however, is that any direct involvement of the exchange program in political affairs would greatly lessen the chances of the program’s receiving adequate financial support from the Congress.

Being a practicing politician I perhaps err on the side of pragmatism—I certainly eschew tilting at windmills. I should hate to see the exchange program go down the drain as a consequence of an attempted boycott which had virtually no hope of serving its purpose.

J. W. Fulbright

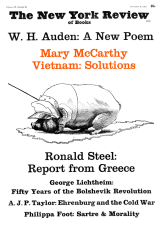

This Issue

November 9, 1967