In response to:

Randall Jarrell's Complaint from the November 23, 1967 issue

To the Editors:

Having been one of Randall Jarrell’s writing students in 1947 and 1948 when he first came to the Woman’s College of North Carolina, and having been profoundly affected by his conversation, his personality, and his criticism, I feel obliged to differ somewhat with Stephen Spender’s impressions of Jarrell as a rather disappointed romanticist [NYR, Nov. 23].

When he first came to us he seemed a rather queer bird, austere, forbiddingly heralded as both brilliant poet and devastating critic, but with a surprising naturalness of movement which reminded us of the childhood we were leaving behind, an ease which seemed to contradict his coldness. He had besides an extremely unacademic manner, and all in all there was something gnomelike about him, something not quite contained in everyday experience, full of sudden surprises and disconcerting impressions. We were a little afraid of him, being young women in a school not well known for its intellectual sophistication—although of course we thought of ourselves as very sophisticated….

Wary as we were, we were fascinated by him. Conveying the impression that he trusted utterly in the adequacy of our good sense and honesty, and the self-evident rightness of the poems or parts of poems he chose for us to read, he led us through a maze of sentimental rnetoric (our own and other writers’) always pointing to the real feelings beneath the false ones, the words that really worked, the sharp illuminations hidden in obscurity. What was genuinely strange, disturbing, queer was apt to be significant and interesting. Jarrell was contemptuous of the self-consciously clever substitution of fake eccentricity and romance for the real intractableness of experience….

He made us love good poems with the passion children give to toys which are not merely companions to them but talismen with which to face the world. He had, and conveyed to us, the professional magician’s delight in a brilliant accomplishment for its own sake. Some of his own poems were clever entertainments which he loved to read aloud for the delight of others and himself….

Jarrell could be cruel and cutting to people on the faculty of the college and of course in his position as critic, but wasn’t that perhaps only where he felt real people, real poems, real ways of feeling to be threatened by abstractions, intellectual or aesthetic pretensions, faddism? He was always extremely gentle, tactful, and graceful with his students, who must have wearied him with many of the banalities he particularly despised.

It seems to me that Randall Jarrell was harsh and unfeeling only with those whom he felt to be his equals in sophistication or who, by placing themselves in the literary arena, made themselves the enemies of genuine excellence, the representatives of those powers, political, aesthetic, or intellectual which threatened the unique, suffering, not very virtuous individual being whom he loved with mingled pity, horror, and delight.

Nancy Seletti

New York City

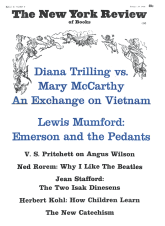

This Issue

January 18, 1968