In response to:

Mistaken Identity from the March 28, 1968 issue

To the Editors:

I am perplexed that a publication which has claimed for itself, as The New York Review of Books so often has, the role of guardian over current standards of literary, intellectual, and political discussion in America can have carried one of the more blatant violations of such standards in recent memory. I refer, of course, to Christopher Ricks’s recent review of Gertrude Himmelfarb’s Victorian Minds. Mr. Ricks is entitled—to have to rehearse the rules of proper entitlement in these matters is simply an embarrassment but obviously a necessary one—to find and expose in a book of this nature whatever political bias he does so find and does so expose, for good or ill. But to have attempted to reinforce the impact of his analysis by identifying the author’s husband—with the implied insulting, breezy, cozy assurance that everyone knows what that means—is just plain beyond the pale: beyond the pale for Mr. Ricks to have written and beyond the pale for you to have published.

Can it be that the editors have forgotten the obligations assumed with the assumption of minimal, let alone high, standards? Or can it be that they have become standard-bearers of another, alas no less familiar, kind, ready to offer special indulgences to those who will march in line.

Midge Decter

New York City

Christopher Ricks replies:

“Identifying the author’s husband?” But since Victorian Minds chooses to proclaim of Miss Himmelfarb that she is “married to the author and editor Irving Kristol”—and since it chooses to repeat this, not just on the jacket, but in permanent print within the book itself—what is wrong with referring to a fact so proudly proclaimed? A month ago, I didn’t even know that Miss Himmelfarb is Mrs. Kristol. Victorian Minds brought it to my attention.

It is true that I wouldn’t have mentioned Miss Himmelfarb’s husband if he had been a John Smith. But then nor of course would Victorian Minds have done so. And by speaking of the “author and editor Irving Kristol,” Victorian Minds corroborates my own view: that Irving Kristol is a figure in the public domain. An analogy would be Iris Murdoch and her husband, the critic John Bayley—there seemed to be no offense in my referring (as I once did in a review of Miss Murdoch) to the fact that she is married to the author of The Characters of Love, many of whose literary beliefs she shares.

Similarly, just as I think that the politics of Mr. Kristol—like those of any “author and editor”—are in the public domain, so I think his politics are relevant to the important question I tried to answer: how could so clear-sighted a writer as Miss Himmelfarb have published—in Encounter, 1960—so muddy an article as that on John Buchan? Because Encounter (edited up to 1958 by Mr. Kristol) sometimes condoned that sort of article. “John Buchan: An Untimely Appreciation”—but even if this rhetorical flourish were accurate in insisting on how inimical the times are, the place was accommodating enough.

Put a hypothetical case: if Commentary were to publish an ill-considered article by Midge Decter, would nobody be allowed to mention the fact that she is married to the editor? Or put another hypothetical case: if Midge Decter were to write to The New York Review protesting, say, about its recent review of Making It, would nobody be allowed to mention that she is Mrs. Norman Podhoretz? Not even if she ordinarily chose to be publicized (as she scrupulously has not) as “married to the author and editor Norman Podhoretz”?

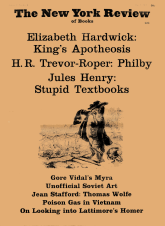

This Issue

May 9, 1968