Probably not many literary people today would agree with my belief that self-consciousness more than any other fault spoils novels. The general feeling is that the novel is a form no longer entirely natural to our culture (any kind of audio-visual slop requiring the services of an army of technicians being more “natural” in our time) and that the novelist, aware of working within a fenced-off literary enclave, must needs be self-conscious. The experimental writer has always been self-conscious in a harmless way (hoping the reader will attend not only to what he is doing but also to the way he is doing it), but once the experiment has been seen to work and the method absorbed, there is a healthy tendency to return to the broad highway of naturalness, telling a story because it is about people and events in which the reader might be expected to take an interest, something that impinges on his own life without the mediating presence of “literature.” I admit that this attitude has produced some famous critical gaffes, starting with Samuel Johnson’s “Nothing odd will do long. Tristram Shandy did not last.” But was it such a gaffe? Didn’t the major achievements of the novel, in England at any rate, come out of the unforced naturalness of Fielding rather than from the narcissistic tradition represented by Sterne? Doesn’t Tristram Shandy live as a wonderful oddity rather than as a seed-bearing tree?

Mr. Jones writes out of a sense of the richness and variety of human beings and their history, and since this involves him in seeing every character and every incident in their full perspective, it would be difficult to say in one phrase what his book is “about.” In one sense, it is about Wales; in another, it is about old age; in another, about the nature of family life; in another, about the impact of the modern world with its formless emptiness on the last remains of a more ordered existence. But to say that it was “about” any one of these things, or all of them, would be to put too cramping a limit on one’s pleasure in the book’s vitality. All these issues crop up in the lives of the characters, as they crop up in our own lives; they occur as causes of antagonism and alliance, of outrage and shock and illumination, and also as opportunities to be seized, continuities to be held on to, tragic facts to be faced. This is a first novel, but it has none of the Look-Ma-I’m-Writing quality of most novels; one feels a personality behind the story, but it is a personality that does not intervene; it is content to preside.

MR. JONES’S STORY concerns an old couple, the widowed Lady Mignon Benson- Williams and her brother Freddy, a clergyman. They live together in the ancient farmhouse in (I think) mid-Wales, where their father was born, though the farm is no longer in production and its land is worked by other people. Mignon and Freddy love and respect the memory of their father, a local M.P. who gave his life to the service of the people of the area, which in practice means fighting the battles of the rural Welsh against the centralizing, urban English. But the past life that becomes active in the story is that of Mignon’s husband, a cautious, discreet Civil Servant who kept a diary full of the comings and goings of those in power. Mignon is quietly desperate. Unlike Freddy, who has genuine saintliness and has made his peace with life and death, she feels that her life is ending on the scrap-heap; it seems to her symbolic of this that the farmhouse badly needs repair and decoration which she cannot afford. A local relative offers the money out of sheer good nature, and, while Freddy with his innocent simplicity longs to accept, Mignon is still too involved with the world, too full of considerations of pride and independence and patronage, to be able to take it. This need for some ready cash is the lever that moves the story into action. Mignon decides instead to offer her husband’s stodgy diaries for publication, and three visitors come down to inspect them. Each in turn reveals himself and each reveals a different facet of the lives of Freddy and Mignon, the character of their relationship with each other and with the world, and the nature of their household.

In addition there is a sub-plot, and it is here that Mr. Jones’s want of experience in the mechanics of novel-writing makes itself uncomfortably felt, though it is to his credit that he has avoided the simplifications that would have made plot and sub-plot easy to dovetail. Mignon’s husband had an illegitimate daughter by a local woman; he also had, by Mignon, a daughter who has shaken off the dust and emigrated to Rhodesia, and who now returns on a visit accompanied by her white-settler son. Their various cross-currents of relationship are enough to make a novel in themselves, and toward the end, when Mr. Jones is working hard to resolve both plots at once, one has the discomfort of listening to a man trying to tell two stories and not sure which should come first. But, by that time, the reader is so involved in the story that it is easy to make allowances.

Advertisement

I felt, on laying down The Three Suitors, that I had been reading about real people; real, not because they existed historically, but because the imagination that pictured them was intent on reality as it is sifted through human experience rather than as it appears in charts and graphs; a feeling I was not often to get as I read through the other novels in this batch. It is also worth noting how little The Three Suitors is damaged by its lack of up-to-dateness. The Wales we find here seems far from the Wales of 1968, which is on the crest of a wave of irritable nationalism that has at last got its hands on political power, facing squarely for the first time the tragic split between North Wales (rural, traditional, scribbled over by the tourist industry) and South Wales (urban, industrial, Anglicized, its national identity coming out most strongly in a working-class culture that is regional rather than national). But the Wales in this book nevertheless exists, inconspicuously embedded in the Wales of 1968; it is composed partly of memories and partly of a blind, stubborn insistence on survival which makes itself felt in Mr. Jones’s story.

IF, as now seems likely, the not very ancient historical bonds of the United Kingdom are going to fall apart in our time, and Wales and Scotland to follow Ireland into separate nationhood within the loose confederation of “the West,” then the problem for Wales will be one of identity: which Wales to be? This is the root of all the bitter internecine warfare currently going on, just as it is the root of similar strife in Brittany, in Ireland, in various new Asian states and, for that matter, in Canada. At which point, enter Mr. Richler, a Canadian living in London. Cocksure is the opposite of Mr. Jones’s book in every way, and two ways in particular: it is intensely up-to-date, and it deals not with real people but with cardboard cut-outs.

This, of course, is by design. Mr. Richler is writing satire, and not only satire but extravaganza; “real,” three-dimensional characters have no part in such a book, because it is a law of satiric extravaganza that everyone has to behave in character at every appearance and to the utmost possible extent. If a character represents Lechery, or Intolerance, then he must never appear in the story except to be furiously lecherous or bitterly intolerant; there can be no light and shade. Once we have got used to this we can appreciate Mr. Richler’s high spirits and inventiveness. Cocksure is a down-with-everything satire taking in progressive education, doctrinaire sexuality, spare-part surgery, profitable hipsterism, debunking anti-heroism in TV programs, liberal political saintliness, Jewish cultural aggressiveness, Negritude…let’s see, have I left anything out? There seems also to be a light dusting of satire about Canada, if only because some of the principal characters are Canadian, but it is too indefinite to be pinned down.

This kind of book is rather old-fashioned, as distinct from traditional as in Mr. Jones’s novel; traditional means having a long continuity, old-fashioned means yesterday’s newness. Much of Cocksure recalls the flickering two-dimensional satire of the Twenties. The central villainous character, the Star Maker, reminds one of middle-period Aldous Huxley—in, say, After Many a Summer; he is a Hollywood film mogul with absolute power of life and death over all his minions, which surely makes him at least twenty years out of date, though the details of how he works are genuinely funny-horrible and ingenious. However, the best thing in the book, for my money, is Polly Morgan, a girl whose mind has been entirely formed on films, to the extent that she has no real experiences at all; e.g., she will invite her lover to a feast, gastronomic or amatory, and suddenly cut from the gleaming preliminaries to the happily sated afterglow, leaving out the main business altogether as films do. The cardboard hero finally meets his death because of this tendency on her part, in a grotesquely neat twist of plot.

Cocksure certainly keeps one reading, and often laughing, and perhaps I sound dyspeptic and square, but, six weeks from today, I doubt whether I’ll be able to remember what it was all about. As Mr. Richler is far too sharp not to know, this is the fate of all satire that lashes out without having a definite place to lash out from—all these modern absurdities are ridiculed, but in the name of what? Only breakneck inventiveness can keep the reader from noticing that the whole thing is an Indian rope-trick.

Advertisement

“THOUGH A QUARREL in the streets is a thing to be hated, the energies displayed in it are fine.” So wrote Keats, and the words came back to me several times in reading Enderby. No less than Mr. Richler Mr. Burgess is writing satiric extravaganza, but his book is given a focal point by the fact that the hero is a poet, and the satire is directed against those things in the modern world that are hostile to poetry and the free exercise of the imagination in general (which means, in practice, nearly everything in the modern world). I shall do a certain amount of grumbling about this book, so it is best to begin by saying that I read it with many exclamations of admiration, and that I can hardly think of any other English writer, and not many American writers, who could come anywhere near its flow of inventive exuberance. It is “a quarrel in the streets,” a quarrel against our time carried on in public, very loudly, but there is a Gargantuan zest in it, a love of extravagance and proliferation, and a feeling for language, that makes its tone much more positive than negative. I was reminded more than once of Wyndham Lewis in The Apes of God, but I think Burgess’s book is better.

My grumbles are probably personal ones. This kind of book I easily tire of; it may be true that “human kind cannot bear very much reality,” but a lack of reality is like a shortage of oxygen; one starts yawning. All the characters except Enderby are puppets, and Mr. Burgess’s hand is in full view. This is largely because of the self-consciousness that clings to his writing, and this seems to be his major fault. Enderby gets married to a young and beautiful widow who inhabits the world of high fashion, honeymoons disastrously in Rome, leaves his wife, tries to commit suicide, is captured and brain-washed out of poethood in a mental hospital, takes a job as a barman, is falsely accused of shooting his ex-wife’s new husband, a pop star, bolts to Spain, and so on, through a dizzying series of incidents which happen because in this kind of book things have to happen; a colossal cast of characters, though “characters” may not be the right word, passes rapidly across the stage to be thwacked by the bladder of Mr. Burgess’s satire, so that by the end of the book (and it is enormously long) one’s moral sense, or whatever it is that makes one appreciate satire, is so numbed that the only reaction left is, “How his arm must be aching from caning so many people!”

It is, of course, the mark of a bad critic to quarrel with the genre rather than with the way the author has acquitted himself in it; but where the faults of a book seem to arise mainly from its genre, what else can one do? I found myself getting most of my pleasure from Enderby himself, but even he is narrowed to a “humour” in the Jonsonian sense. Enderby is a poet who cares for nothing except getting on with his poetry, a premise so unreal that I found it difficult to believe in him as a poet at all, in spite of the fact that Mr. Burgess has taken the trouble to write many skillful poems on his behalf, some of which appear, Zhivago-like, in an Appendix.

MR. PRICE’S Love and Work gives us another contrast; the short, tightly organized nouvelle, with a restricted cast, all of whom are analyzed fully. I promised myself much enjoyment from this book, but was in fact nearly defeated in my effort to read through it by a self-consciousness so persuasive as to make Mr. Burgess seem Arcadian. The style (terse, loaded, lyrical) is worked so hard that one longs to come across a sentence written casually, just to convey a piece of information; and the overall plan of the story is so neat, so buttressed by symbolism at the foreseeable points of stress, that the total effect is lacking in spontaneity. In spite of this, the book is worth persevering with, for Mr. Price has important things to say.

A writer, young enough to have most of his life and work ahead of him, is anatomized, as by a slow-motion camera, amid the conflicting tensions of, precisely, his work and his various loves. He loves his wife, he loves his mother who dies in the opening pages, he loves the memory of his father. Since the work he is currently engaged on is a reconstruction of their young lives before he existed, the preoccupations all knit together. Strain, doubt, his wife’s intelligent pain at his apparent withdrawal into a fortified working self, all mesh with his conflicting emotions on clearing up his parents’ house and burning piles of old letters, the last residue of their lives. The situation is effectively imagined, and the story concludes—or rather spins out of sight on its final pivot—with a real surprise. With all this to sustain it, the book could have spared the relentless over-writing, and even more the dado of symbolism. On his way back from burning the papers, the hero comes on a wrecked car with a dying young man inside. The death is described with agonizing realism, and then follows the neat bow that ties up the symbolism: a quotation from the Odyssey, a bit of literary-anthropological commentary about feeding the dead with blood so that they will give up their secrets—suddenly the interest of following a story is replaced by the interest of listening to a piece of “explication” offered to a Creative Writing class (the hero, ominously, teaches one) and the two kinds of interest don’t mix. Which is, perhaps, another way of saying what I said at the beginning.

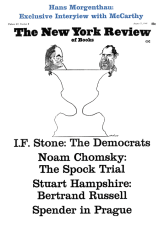

This Issue

August 22, 1968