In response to:

An Open Letter to Michael Harrington from the December 5, 1968 issue

Editors’ Note: After the appearance of Dwight Macdonald’s “Open Letter to Michael Harrington” in the December 5 issue, Mr. Harrington requested space for the article that appears below. Mr. Macdonald will reply in the next issue.

An Open Letter to Men of Good Will (With an Aside to Dwight Macdonald)

The New York City school crisis has the aspect of an Antigone-like tragedy. On one side, there are those who justly denounce miseducation in the ghetto which, in this technological society, effectively programs innocent children for a life of adult poverty. On the other side, the members of one of the most progressive labor organizations in America—on issues stretching from civil rights to Vietnam—assert principles of academic freedom and due process when a professional is dismissed from his or her post.

So there is not a simple conflict of right and wrong but an antagonism of two rights. As a result, you are torn no matter what position you take.

I was sensitive to these complexities and ambiguities when I helped initiate the Right to Teach statement which supported the union on the basic issue in dispute: whether or not there had been a violation of due process at Ocean Hill-Brownsville. I resolved my conflicting loyalties in this fashion for two reasons. I was convinced—and I most emphatically still am—that substantial procedural rights had been denied the teachers and therefore, on the specific issue in contention, the union was right. Secondly, and even more fundamentally, I felt that the local board’s tactics would not advance the goal of genuine, effective decentralization which I also advocate. I thought that the version of community control being urged in Ocean Hill-Brownsville gave unwitting support to a conservative, and even reactionary, position. And I believed that any decentralization plan which abrogated union rights was politically doomed to failure.

As the conflict escalated, no decent person on either side could be happy. New York was racially polarized as never before; hundreds of thousands of public school children were not being taught; and the parent-teacher relationship in the slums was transformed from alliance (which it had been only a few years ago, when, for instance, the UFT supported the first school boycott) to bitter antagonism. Clearly, then, this was not a traditional labor dispute pitting worker against boss, nor a traditional freedom struggle of black against racist. So without changing my basic view of the issue, I favored the quickest possible just resolution of the strike.

Now the dispute may be over (though as I write on December 4, there are persistent reports of violence and breakdown of the agreement). Nothing constructive will be accomplished by rehearsing the old issues at this point, for what is needed is reconciliation between the black parents and the union teachers, difficult as that may seem. If such a rapproachement does not take place, all the indicators point to a worsening of the status quo ante. The legislature, responding to backlash sentiments, will end the entire decentralization experiment; the ghetto will be stuck with the same utterly inadequate schools, and the fact will be all the more intolerable because it will be more widely known by the victims; and the hostility of black and white, parent and teacher, will be institutionalized with disastrous consequences for all progressive causes.

So the main, substantive point of this Open Letter is to try to clarify the decentralization question itself as part of a dialogue among the men of good will on both sides who favor real, effective community involvement in the educational process. Unfortunately, I must preface this serious point with an aside about Dwight Macdonald’s comments to me (New York Review, December 5).

Macdonald tells how our personal relationship dates back to 1952. He accurately states what I have often acknowledged publicly: that his New Yorker review of The Other America helped transform the fate of that book, the issue which it raised, and its author. For that I have been, and still am, grateful. Macdonald then honors these sixteen years of friendship by betraying a confidence which he explicitly states he knew I did not want made public. He does so through serious misquotation which makes me look treacherous to my friends and hypocritical to my opponents. He prefaces this flagrant violation of the most elementary code of friendship by implying that my ethics are so suspect that a man as principled as Dwight Macdonald cannot ever discuss morality under the same roof with me. In the process, Macdonald proves himself more reprehensible than a wiretapper, for he uses intimacy, rather than electronics, to do his dirty work.

Macdonald says that through sloth, ignorance, and misplaced trust in me, he signed a statement which did not even have prima facie validity. Having thus established his expertise, he is now so infallibly certain of the facts in Ocean Hill-Brownsville that anyone who disagrees with him is either ignorant and slothful, as he himself was only yesterday, or deceitful. For my part I am willing to grant the sincerity of the majority of intelligent, decent people on both sides—and even to entertain the possibility that I am wrong. Indeed, when Macdonald first discovered how stupid he had been, and how right he had become, I helped supply him with the names and addresses of all his fellow signatories so that he could invite them to a meeting where spokesmen of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville board would try to persuade them to remove their names from the “Right to Teach” ad.

I was out of town and could not attend the session but I sent Macdonald a friendly wire telling him that I hoped that concerned people on both sides could carry on a dialogue. My reward for this essay in fraternity was Macdonald’s semi-fictional, garbled version of our private conversation.

On the issues which Macdonald raises in this duplicitous way, I will be brief for the reasons I stated earlier. I am convinced that the UFT was genuinely for decentralization, in part because the first advocate of this kind of a plan to whom I talked was Al Shanker. In 1966, he asked me to write an article on the union’s advocacy of such an approach and particularly insisted that the local boards would have to have independent funds of their own. (I referred briefly to Shanker’s position on page 130 of Toward a Democratic Left, which was completed in October, 1967, almost one year before the strike.) Moreover, through the League for Industrial Democracy I helped organize, and attended, off-the-record conferences which brought together union leaders, black advocates of community control, and people from City Hall and the Ford Foundation. We tried to discuss and resolve the differences within the group, and though we obviously failed spectacularly, the experience convinced me that the union was indeed for decentralization even though it differed with some of the black leaders present. (Not being a licensed moralist like Dwight Macdonald, I am not at liberty to report on these closed meetings in any detail.)

Secondly, I remain convinced that a due process issue was very much at stake, and that the ad was right on this basic count. But since I don’t want to stir up old animosities I would simply refer Macdonald, or anyone else who is interested, to Maurice Goldbloom’s excellent critique of the New York Civil Liberties Union Report. (It can be obtained from the Ad Hoc Committee to Defend the Right to Teach, Room 1105, 112 E. 19th Street, New York City.) It contains documentation for my position which I find persuasive.

I should also note that Macdonald did not simply publicize a friendly, explicitly private conversation, but he did so in such a distorted way—I will assume unwittingly—as to suit his own purposes. I did indeed have tactical differences with the union leadership at certain points in the strike, and I spoke to Al Shanker about them in a private meeting which will remain private. Macdonald’s second-hand and remembered transcription of this conversation—heard, so to speak, through the keyhole—is erroneous in significant sections. It also publishes details which one might even think malicious: I have not used the term “colored,” which Macdonald attributes to me, since I was a boy in St. Louis. When he put the word in my mouth, did he know it suggested genteel, middle-class racism?

I have long thought Dwight Macdonald charming and decent. His lack of diplomacy seemed a mark of integrity, his constant changing of positions a sign of restless honesty. He was our own Pierre Bezuhov. But there is no holy obtuseness, no saintly stupidity, which justifies the betrayal of a friend. In The Root Is Man, Macdonald rightly identified the notion that one sacrifices the present, living generation in the name of a distant future as a source of Stalinism. And now that the preacher has used a personal relationship as an expendable means for his political ends, he lectures me on morality.

But let me turn to the real issue: how to develop effective decentralization of the New York school system.

When the union, and others like myself, objected to the original Bundy proposals on the grounds that they would create too many school districts, some took this as an evasion on the part of the enemies of community participation. I simply do not think that is true. Even more to the point, I believe that some of the militants and radicals who have embraced an extreme version of local control (small, neighborhood, or near-neighborhood units of administration) are the unwitting agents of a reactionary scheme which could do much harm to black and Spanish-speaking children. Therefore it is precisely because I want decentralization to work that I am opposed to the proposal in this form. And I think there is some mighty fancy manipulating going on among some of the corporate liberals who have made an alliance with some black powerites.

Cutting up the city into a multiplicity of districts has many dangerous consequences which are so obvious that I will only list them. It institutionalizes segregation (and I am for integration on moral, economic, social, and educational grounds). It opens up the possibility of political, and even witch-hunting, job criteria in units which are so small that they can be dominated by a minority of activists, whether of the Ultra Right or Ultra Left. It could lead to a fantastic reduplication of effort in contiguous districts and a resultant waste of resources which would injure every school in the city. It would allow middle-and upper-class city dwellers to imitate the worst example of their suburban cousins by effectively establishing lily-white public prep schools in order to maintain the unfair advantages which their children have.

These are just a few of the objections to the notion of the neighborhood school unit of administration. But there is an even more pertinent point which a recent ad of the New York Urban Coalition illustrates perfectly and outrageously. Entitled “If it works for Scarsdale, it can work for Ocean Hill,” this statement is either unbelievably incompetent or else the most obscene act of Machiavellianism on the part of white corporate wealth in recent years.

“Scarsdale,” we are told, “has one of the finest school systems in the United States.

“It has 5,122 students. And a school board consisting of seven members. Which makes one board member for every 732 students.

“New York City has much the same system.

“It has 1,100,000 students. And a Board of Education consisting of 13 members. Which makes one board member for every 84,615 boys and girls.

“The arithmetic alone shows us why our school system is in trouble…

“Doesn’t anybody give a damn that less than 25% of our high school graduates go to college?

“And that the figure for Scarsdale is 99% …

“Doesn’t anybody give a damn that 55% of the children in our public schools are behind in reading?…

“If you give a damn about our children, we see only one answer.

“Community control of the schools.” (Emphasis added. I have skipped about half the ad but not changed its essential meaning.)

Now this is, of course, the most preposterous sociology and economics one can imagine. You take a white, upper-class suburban community in which the overwhelming majority of the parents are college graduates, and where practically everyone enjoys the benefits of affluence. You then use the zoning power, and other techniques, to wall off this island of prosperity from the sea of urban troubles in New York City. And, if that is not enough discriminatory advantage for such a community, just to be sure that the kids will stay way ahead of the blacks and the poor, you spend much more money on their schooling than impoverished communities can afford. So it was in 1966, the White House Conference on Civil Rights noted that those seven board members in Scarsdale accomplished their prodigies in part because they spent $1,211 per capita on each child while rural Georgia was paying out $265 a year and Cleveland $447.

You then compare this suburb, with its princely Federal and state subsidies, with the most victimized, disadvantaged black ghetto areas of New York. And ignoring the whole institutionalized, corporatized system of economic and social racism, you argue that the difference in educational achievement in the two areas is a function of the structure of the school board. And therefore, the clear implication goes, if only there is community control in Ocean Hill-Brownsville, then there will be rapid progress toward a 99 percent figure for college entrance. The slums are left to rot; no new appropriations are mentioned for school buildings, teachers, or equipment; and there is painless, costless, and fundamental change.

It can be justly argued that this is an extreme statement of the case and that the more intelligent supporters of a great number of small districts do not buy this propagandistic thesis. There are two important comments which have to be made to such a response.

First of all, as the battle lines hardened during the strike, the partisans of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville board tended to make centralization the problem, community control the solution, and to regard even the most sincere statement of the case for a limited decentralization within larger, integrated, and economically functional units as treason to the cause. Now that the day-to-day escalation may have come to an end, isn’t it possible to discuss the complex causes of ghetto miseducation in a more serious way?

Moreover the fact that some of the Ocean Hill-Brownsville supporters, even those on the Left, adopted Goldwaterite economic arguments in defense of their position shows how reactionary the logic of this panacea can be. I expect a Milton Friedman to believe that if, in a class-stratified and institutionally racist society, one gives each family unit a voucher and allows them to bid for education on the “free” market, that will result in justice. That has been the conservative argument for some centuries now. But people on the Left should certainly understand that the exercise of such equal rights to education within a profoundly unequal economic and social structure will shore up privilege and intensify discrimination. That is not theoretical speculation; it is historical fact.

Indeed, I would argue that a certain measure of financial centralization is necessary in the New York school system precisely in order to allow for greater per capita funds to go to areas with higher per capita disadvantages of housing, health, income, and like. If, however, there is going to be an “equal” competition among a multiplicity of community boards, then the districts with the greatest economic, social, and political power will prevail. (Ironically, The New York Times reports that the Urban Coalition is supporting my position in a Detroit Lawsuit. Why, then, does the New York Coalition take a full-page ad which rebuts the parent body’s attitude in Detroit?)

I am ready to assume quite sincerely that most of the black community control enthusiasts and their white supporters are led to a potentially dangerous and conservative position by an understandable outrage against the indignities of the status quo and a determination to try something, almost anything, new. I do not feel so kindly about the Urban Coalition.

The great impetus for the decentralization controversy in New York came from two Republicans, John Lindsay and McGeorge Bundy. If the notion of corporate liberalism has any relevance—and, as I pointed out in Toward a Democratic Left, I think it does—Mr. Bundy is eminently qualified to be included in, and Mr. Lindsay only a little less so. Now they are joined by the Urban Coalition in backing a scheme which is the very essence of Let Them Eat Cake! In order to get the children of Harlem up to the educational level of those in Scarsdale, it is not necessary to invest in decent housing, build new towns, create genuine full employment, or even make a modest little contribution to improving the quality of segregated education in the slums right now. It can all be done by that magic change in the structure of the Board of Education which is going to abolish the three centuries of racism which are so incarnated in our basic economic institutions.

What becomes almost obscene about such a reactionary shell game—with all those pious “give a damns”—is that these very same corporate chiefs are right now planning an increase in unemployment in order to protect the stability of prices and the worth of the dollar in Scarsdale at the expense of the poor in Ocean Hill-Brownsville. At its October meeting the Business Council—which is about as close to an executive committee of the American haute bourgeoisie as one can get, and contains some of the most socially conscious Give-a-Damners in the country—discussed hiking the jobless rate to 5 1/2 percent or 6 percent. And although there has not been much candid talk about the scheme since, there have been enough hints that the Nixon Administration will fight inflation in this cruel manner.

The most monstrous part of this situation is that it allows Urban Coalition executives to parade as the allies of militant black power even as they, or their allies, are preparing to increase black unemployment. And that is a particularly insidious form of corporate liberalism since the only concessions it makes to the poor in order to strengthen the status quo are psychological. For though a community board might have the appearance of control, effective power will be exercised by the major economic and social forces manipulated by the corporate leaders. Under such circumstances, it is small wonder that people like Barry Goldwater and William F. Buckley, Jr., have had kind words to say about black control of black misery and white control of the nation’s wealth. What is surprising is that people on the Left should join in the chorus.

All of us became, I am sure, somewhat polemical and sloganistic under the pressures of the strike. But now it should be possible to have serious discussions of the complex causes of miseducation in the other America and the need for massive, democratically planned social investments, as well as functionally structured decentralization, in order to do something about the intolerable situation. I understand perfectly well that a Nixon Administration is not exactly likely to adopt the necessary policies and that, in the immediate future, there may be no choice except to settle for a slice of bread rather than a loaf. But the reality must be accurately described so that, when the political possibility of effective action once more emerges, the partisans of social change and genuine black freedom will know what to do. And that cannot happen if all criticism of the community control version of a decentralist panacea advocated by both militants and the corporations is seen as treason.

The growth of race consciousness and pride in the black slums of America is one of the most momentous and positive developments of the decade. But that new spirit must now inspire economic and social programs capable of dealing with the enormous, interconnected outrages suffered by the black masses. There are militants who say there must be a transfer of resources and power from the white rich to the poor, both black and white. Precisely! But that is not done simply by changing the structure of the school board, as the New York Urban Coalition would have one believe. It requires, among other things, a new majority including both blacks and trade unionists joining in a common struggle. And it would be a sad day if the Left were to buy the sophisticated, reactionary argument of big business for inaction and the intensification of the economic and social bondage of black Americans.

If the strike is over, as I fervently hope, it is time for the most earnest discussion, not for recrimination. Either those of us who were on different sides of the immediate issue, but who share common values and concerns, will once more come together or else the only victors in the tragedy will be backlash and poverty.

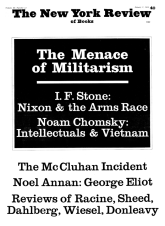

This Issue

January 2, 1969