In response to:

Slavery, Race, and the Poor from the March 13, 1969 issue

To the Editors:

In his review, “Slavery, Race, and the Poor” in your issue of March 13, J.H. Plumb writes that the Elizabethan English believed in “the eternal, God-given inferiority of the Negro” and that “These attitudes toward the Negroes made the enslavement of them by the English both natural and ferocious.”

There is, however, evidence that some Jacobean Englishmen regarded slavery, even of non-Christian colored people, as wrong. Sir Thomas Roe, English Ambassador at the court of the Great Mogul, several times expressed his abhorrence of it. Two extracts from his Journal will suffice. On March 23, 1616, after the Great Mogul had offered him a Mogul convicted of felony as a slave, Sir Thomas wrote,

I returnd thancks: that in England we had no slaues, neyther was it lawfull to make the Image of God fellow to a Beast: but that I would vse him as a seruant, and if his good behauiour merited yt, would giue him libertye.

In this next extract, not Indians but Negroes were involved. The Great Mogul, Sir Thomas wrote, on November 6, 1617,

sent to mee to buy three Abassines [sc. Abyssinians] (for fortie Rupias a man) whom they suppose all Christians. I answered: I could not buy men as Slaues, as others did, and so had profit for their money; but in charity I would give twenty Rupias a piece to saue their liues, and giue them libertie.

Sir Thomas was keeping his Journal for eventual delivery to his employers, the East India Company, and he must have assumed they would share or approve his views. If such views were a new development from the previous reign, it would be interesting to know why such a change had come about; and how widely such views were held between the early seventeenth century and the rise of the great anti-slavery agitations in the late eighteenth.

Marghanita Laski

London

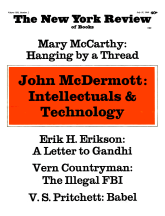

This Issue

July 31, 1969