INTRODUCTION

Thirteen years have passed since 1956, when I began my study of Jesús Sánchez and his children, Manuel, Roberto, Consuelo, and Marta, in a Mexico City slum. In 1961 I published my book The Children of Sánchez, but this did not mark the end of the study nor did it terminate my relationship with the family. Indeed, we have been in constant touch and not a year has passed without my visiting them. Many important changes have occurred in their lives. Here I shall limit myself to relating a single dramatic incident, the death of Guadalupe, the maternal aunt and the closest blood relative of the Sánchez children.

Although Guadalupe was only a minor character in my book, she played a central role in the Sánchez family. Moreover, ‘she, her husbands, and her neighbors in the vecindad, were better representatives of the “culture of poverty” than were Jesús Sánchez and his children, who were more influenced by Mexican middleclass values and aspirations. In December, 1962, one month after Guadalupe’s death, I returned to Mexico to study the effects of her death upon the family. This articles is drawn from my book, which is based upon taperecorded interviews with Manuel, Roberto, and Consuelo Sánchez. It presents three views of their aunt’s death, wake, and burial.*

Their stories highlight the difficulties encountered by the poor in disposing of their dead. For the poor, death is almost as great a hardship as life itself. The Danish novelist, Martin Andersen Nexö, writing in his autobiography about his early life in a Copenhagen slum, recalls that when he was about three years old he asked his mother whether his brother, who had recently died, was now an angel. His mother replied, “Poor people don’t belong in heaven, they have to be thankful if they can get into the earth.” The struggle to get Aunt Guadalupe decently into the earth is one of the basic themes of their story.

Guadalupe died as she had lived, without medical care, in unrelieved pain, in hunger, worrying about how to pay the rent or raise money for the bus fare for a trip to the hospital, working up to the last day of her life at various pathetic jobs, leaving nothing of value but a few old religious objects and the tiny rented space she had occupied.

Both her life and death reflected the culture of poverty in which Guadalupe lived. Her life was a story of deprivation and trauma. Born into a poor family in Léon, Guanajuato, in 1900, she was ten years old when the Mexican Revolution began and twenty when it ended. Thus she lived through some of the most difficult years in the history of Mexico, when bloodshed, violence, hunger, and much suffering occurred. Her sad experiences, not unusual for those times, help us to understand her situation at the time of her death.

Guadalupe was one of eighteeen children, only seven of whom survived their first year. Her parents were religious and had been properly married in church. Illiterate, they supported themselves by making native sweets which they sold in the plaza. The extended family was small and they had few relatives to help them. Both sets of grandparents were dead by the time Guadalupe was born. She did not know where they originated but they were probably part of the urban proletariat in León. Guadalupe’s parents spoke no Indian tongue and, as far as we know, they followed no tradition other than Mexican folk Catholicism.

The Panaderos vecindad where she lived consisted of a row of fourteen one-room adobe huts about 10 by 15 feet, built along the left side and across the back of a thirty-foot wide bare lot. The rentals for the huts were from $1.60 to $2.40 a month. The average monthly income in the vecindad was $8.40. Guadalupe and her first husband, Ignacio, were among the very poorest, with a combined monthly income of only $5.20. When she died, Guadalupe’s worldly possessions were worth only $121.13.

The empty lot was enclosed on two sides by the walls of adjacent brick buildings and in front by a recently built brick wall with a narrow open entrance that leads to the courtyard. The only pavement in the yard was a walk of rough stone slabs laid by the tenants themselves, in front of the apartments. Five of the dwellings had makeshift sheds, constructed by setting up two poles and extending the kitchen roofs of tarpaper, tin, and corrugated metal over the low front door-way. The sheds were built to provide a dry, shady place for the artisans who lived and worked there. Piles of equipment, tin, bundles of waste steel strips, wire, nails, and tools, kept on old tables and benches cluttered the covered space. Toward the rear of the yard, two large cement water troughs, each with a faucet, were the sole source of water for the eighty-four inhabitants. Here the women washed their dishes and laundry and bathed their children. In the back of the lot two brokendown stinking toilets, half curtained by pieces of torn burlap and flushed by pails of water, served all the tenants.

Advertisement

The rest of the lot, strewn with stones and filled with unexpected holes, was criss-crossed by clotheslines held up by forked poles. In the daytime, the lot was filled with children in ragged clothing and ill-fitting shoes, or barefoot, playing marbles or running between the lines of laundry, heedless of the warning shouts of the women. Children, barely able to walk and still untrained, sat or crawled in the dirt, often half-naked, while their mothers watched them from where they were working. In the rainy season the yard became muddy and full of water so that it sometimes flooded the low dwellings.

I

THE DEATH

Manuel:

It was November 2, the Day of the Dead, and I was still in bed at about eleven-thirty in the morning when we heard someone knock. My wife opened the door to the courtyard and a voice outside said, “Good morning. Is señor Manuel in?”

“Yes, he’s here, but he isn’t up yet.”

“Who is it?” I shouted.

“Pancho, señor Manuel.” Pancho was the husband of my aunt’s niece and right off I had a premonition of what he had come to tell me. “I just came to tell you that your Aunt Guadalupe is stretched out on the floor of her house, bleeding.”

I sat up quickly, pulled on my trousers, and bent down to look under the bed for my shoes. I put them on without bothering to look for socks. Pancho said, “Well, I’m going now. Don’t take long, señor Manuel.”

“All right, thank you,” I called, “I’ll be there right away.” I ran a comb through my hair and looked around for my jacket.

“Get going, Manuel, your aunt may be dead already, hurry up!” Maria said.

“All right, hombre, I’m coming. Go to the market and tell Roberto to fly to my aunt’s house. Tell him to go right away, even if he hasn’t sold anything yet.”

As I started for the door, in walked Gaspar, that character my aunt took up with after her husband died. I didn’t like Gaspar. He was only thirty-five and my aunt was sixty. What could he be after but a home at her expense? He had sly little eyes and I figured him for a bad character from the first time I saw him. He was short and skinny with a yellowish brown skin and the typical strawberry nose of an alcoholic. He never looked good but on this morning he looked ghastly. One could see the anxiety in his face. His lips were dry and his teeth clenched so hard his cheekbones stood out more than usual. He said, “Please, please, come quickly. She’s just stretched out there, she’s killed herself….”

“What do you mean, killed herself?”

He stood with his arms hanging at his sides, nervously opening and closing his fists. “Well, I don’t know, she’s just lying there.”

“Come on, let’s go.” I rushed through the door, down the courtyard, and out of the Casa Grande. The Street of the Bakers, where my aunt lived, was two blocks away. As I hurried along I had the same guilty thoughts I always have when something like this happens. ‘Poor old woman! How is it possible that she could die all alone like this? She who was always surrounded by people? And me so slow about helping her out. A hundred pesos means nothing to me but what pleasure it would have given her, even if it went for alcohol or to help someone poorer than herself. It really made her happy to help others. I should have come to see her more often, if only for appearance sake. But no, why should I if I didn’t feel it? And every time it would have cost me money I didn’t want to give. Why be a hypocrite?’ Me, the eternal hypocrite, used that to excuse myself!

From the corner I could see people gathered at the entrance of my aunt’s vecindad. Most of them had come just to satisfy their morbid curiosity and I felt uneasy as we approached. We pushed open a path through the crowd and entered the muddy yard.

Gaspar went ahead but I stopped a moment to look around. There were a few women at the wash tubs toward the rear of the yard, scrubbing as usual, for most families took in laundry. The rickety buildings, lined up along one side and in the back of the lot, looked as though any strong wind would blow them down. The common toilets, the snarling dogs, the dirty kids…. I never could understand how anyone could come out of such a place with a smile on his face because living there could mean only one thing, that his entire life was a failure. That’s why I’ve tried to keep myself indifferent to the people there…because I had enough problems of my own.

Advertisement

A small crowd of people blocked the doorway of my aunt’s house, which was the first in the row, next to the shoemaker’s shop. Julia, the wife of Guillermo, saw me and said, “We’ve already called the ambulance, Manuel. She’s dead.” The crowd formed a circle around me, watching me closely. I said nothing and went quickly inside to see my aunt.

Yes, there she was, the poor old woman, on the floor, with Gaspar sobbing over her. Her small body was curled awkwardly, her right cheek resting on the cold cement in a puddle of blood. Her right arm was caught beneath her, with only the palm of her hand showing; her left elbow pointed rigidly toward the ceiling. A sewing basket was clutched in her left hand. I could see the silver ring and the four copper ones she always wore on that hand. Her long dress covered her almost to the ankles. Her feet in their worn black shoes lay in another pool of blood. I bent over her to see if she was still breathing and I felt for her pulse, but there was nothing. The only thing that moved was her thin white hair, blowing in the cold draft that came in through the open doorway.

I looked at her face and its quiet sweetness comforted me a little. If was as if in the brief moment between life and death she had looked into the distance with the inner eyes of her soul and had seen a beautiful place, flowered and peaceful, where she would no longer suffer hunger and misery.

On the right wall of my aunt’s poor little room, the holy images of saints and virgins in their wooden frames contemplated without grief the lifeless body on the floor. The picture of my dead mother on the rear wall seemed to stare at me reproachfully for having neglected her sister. Below the picture, between the bed and the wardrobe, was an unpainted pine table decorated with purple tissue paper and strewn with yellow zempazochitl flowers. On this my aunt had placed her offerings to her dead—several glasses of water and three cheap votive candles which were still burning. Being from Guanajuato, my aunt was “mocho,” fanatically religious, and no matter what her financial state, she always provided something on the Day of the Dead. This year she hadn’t had enough money to burn incense to attract the spirits of her deceased relatives or to buy fruit or chicken or bread for them, but she had left water for the souls to quench their thirst, and candles to light their way. She even bought an extra candle for the dead who had no family to look out for them.

Flies were beginning to gather over the body and I brushed them away. I couldn’t bear the scene any longer. Everything oozed of death. I went outside. There the children, trying to look in, were tearing at the cardboard patches on the outer wall of my aunt’s kitchen. “What are you kids doing? Get out of here, go home!” I said. Some of the children moved away, but others took their places.

I went to ask Julia how it had happened. She was standing with Matilde, Pancho’s wife, at the entrance of the vecindad, gabbing as usual. Matilde, dressed as poorly as ever, had been the last one to talk to my aunt and was telling everyone about it. She repeated the story for me. Her face showed no sorrow as she spoke.

“You see, Manuel, I came by this morning and said to Lupita, ‘I’ll bring you your taquito and coffee in a moment, auntie. How do you feel?’ ‘Fine,’ she answered. Imagine! ‘Ay, daughter, don’t forget my little cup of coffee.’ ‘Now, aunt,’ I said, ‘didn’t I say I’d bring it in a moment?’ And I left. But before I got back, one of the kids came running up to my old man shouting ‘Pancho, Pancho, Lupita is dead. She fell down and has a lot of blood coming out of her head.’ So my old man comes out and sure enough, there she was on the floor. And right away he went to call you.”

“Why doesn’t the ambulance get here?” said Julia impatiently. “We’ve already called them three or four times and still those bastards don’t come. And what about Roberto?”

“I’ve already sent for him, Julita, I don’t think he’ll be long.” I stretched my neck toward the Street of the Barbers, but neither the ambulance nor my brother was in sight.

“Ay, hombre, what a sad end for your poor aunt. And I can’t even shed a fucking tear. I don’t know why, I just can’t,” Julia said shrugging her shoulders, “but believe me, Manuel, God forgives people like her. At least her suffering is over, and she’s rid of that ugly bastard Gaspar.”

None of the neighbors liked Gaspar. They said he was taking advantage of my old aunt, and beating her, too. When I had first heard that rumor I had gone to see her and to meet Gaspar face-to-face so he’d know she had someone to back her up. He was a shoemaker and it was risky because he could pull one of his knives on me. But both he and my aunt denied that he beat her. He said, “It’s a bunch of lies from a bunch of jealous old women. Why would I want to do her harm if I love her? How much do I love you, old girl, how much? Tell him, tell señor Manuel. Those women are just jealous of your marriage.”

I decided to wait by my aunt’s door and I went back into the vecindad. Roberto arrived, pale and panting.

“Well, brother, what’s up?”

“Go on in, but don’t move her because she’s already dead.”

“No!!” That was all he could say, and he quickly went into the room. I followed, and there he was, caressing my aunt’s white hair. He put his hand on her chest, hoping to feel her heart still beating. Then he started to lift her.

“No, little brother, don’t move her. She’s already dead. Can’t you see she’s lost all her blood?” And his eyes filled with tears.

“Poor thing…my poor dear aunt! Ay, Manuel, I feel so guilty. When I think how much money I’ve squandered that I could have given her. Just look at that,” he said, pointing to the small charcoal brazier which showed no sign of having had a fire recently. “She hasn’t cooked for days. And she always acted strong! Just the day before yesterday I asked her if she’d had lunch and she answered, ‘Of course, meat and beans.’ Meat and beans indeed! My poor little aunt. Now there she lies, the last of the Vélezes.”

My brother looked as though he was about to cry. He was really upset. He felt closer to my aunt than I did and spoke affectionately of her but I had always thought it was just out of his own sentimentality because, sticking to the facts, my aunt never showed very much affection for him, or for any of us, in my opinion.

I never felt as if my Aunt Lupe was my mother because she never gave us that kind of love. I was fond of her because she was my mother’s sister…a family tie, that’s all it was. When my mother was alive, my aunt was a steady visitor at the house but that was because she enjoyed a little drink. My mamá was pretty active in that direction herself so that’s why Lupita came around so often. But my mother was a go-getter and always had a peso or two more than my aunt and uncle did. So every time they came it was to have a meal or a drink or to borrow money.

When my mother died, my Aunt Lupita came to take care of us but she was there more as a servant because my father paid her a salary. She took care of us but I don’t think it was anything more than a routine thing. It would never have occurred to her to give us a sign of affection or to say anything nice to us. She liked to be helpful to people and to have everybody think well of her but our relations were…well, I could see that she felt more affection toward the bums who came there to drink with her. She spoke to them with more confidence, as if she felt closer to them. With us, she used that tone of authority, just like my father. Born to command, like my papá!

I didn’t see much of my aunt until after my uncle died. Naturally, when she felt she was getting old, she fell back on us. By then I was married to Maria and we would both go to see her. Each time it cost me five, ten, twenty pesos. But I must say Lupita never asked for a thing except when she was sick. We lived so estranged. Maybe because she was like me and wanted it that way. The further away my family is, the less problems they cause me. In that way, I’m a little more independent. Maybe that’s what she was trying to be, too.

“Listen,” my brother said. “We’ve got to give her a decent burial. But how? Uncle Igancio’s funeral cost us 500 pesos. Look, I’ll go see how much I can borrow from my godmother, though I owe her 200 pesos already. If the ambulance comes don’t let them take her away, because then it’ll cost a lot of money to get her body out of there. I’ll be right back.”

He turned and left quickly. A little later we heard the ambulance siren screaming.

“Here they come, here they come!” chorused all the neighbors and snoopers. The ambulance stopped at the entrance and a young doctor in a white uniform stepped out, with two stretcher bearers right behind him. I opened the rickety wooden door for him. He looked at the body and asked, “Well, what happened to this woman, señor? Just look at her!”

“I don’t know, doctor, she was already like this when I arrived.”

Gaspar stepped forward to give the doctor my aunt’s card for the General Hospital. The doctor read the dates, shook his head, and said, “Ay, qué caray, there’s nothing more we can do for this woman, she’s dead. Now what you have to do is notify the police and they will certify the death. Meanwhile, don’t move her. Take this card to the precinct to prove that this woman was being treated. Maybe they’ll dispense with the autopsy.”

The doctor and the bearers left and the crowd began to disperse.

“Well, Gaspar, go quickly to the police,” I said almost in a tone of command.

“Yes, yes, señor Manuel, I’ll go right away, I won’t take long.”

Gaspar left and I took a stool and sat down outside the door.

Roberto:

When my Aunt Guadalupe began to complain that she had a lump on her behind and that it bled and hurt a lot, I asked her, “Aren’t you doing anything for it?” She replied, “Yes, of course, Gaspar is treating me.” If it wasn’t Gaspar it was another of those people she thought had magical powers.

There was a time when she wanted to go to the hospital to be cured but I couldn’t take her right away because I was out of a job “Give me a few days to find work, so I’ll have money to take you to a private doctor,” I told her. But when I saw that she was getting worse I said, “Look, aunt, if you want to go to the hospital, go ahead. You will be much better off. Everything is clean there, and at least you will get three meals a day. I don’t believe that Gaspar takes care of you, even though you say he does.”

“Ay, no,” she said, “but Gaspar is out of work. The other day his good-for-nothing boss had him make some shoes and hasn’t paid him yet. Can you imagine?”

She always told me the same story, because that’s what Gaspar told her. But I could see through him. He didn’t know that I, Roberto Sánchez Vélez, was the King of the Liars. I never believed Gaspar’s stories although it is true that he knew how to work. He would get his tools together, a knife, a hammer, some pliers, and would work well for a few days, but after a while he would pawn them so he could go get drunk. The result was that my aunt never had three meals in one day, I am sure of that. This hurt me very much, because I felt to blame for what had happened to her. When I had had money, more than enough to have given her some, I hadn’t done it. Oh, I had helped her a little, but it wasn’t enough. For a moment I was tempted to steal. I used to be able to get two, three, or four thousand pesos easily, but I was harming half the people in the world without realizing it. My only thought had been for what I could get for myself. But I honestly didn’t want to do it anymore, because—it is no disgrace to say it—I don’t know why, but before God I was afraid.

And so it went until the time came when I told her, “All right. I will come tomorrow to take you to the hospital.” And she said, “I will appreciate it with all my heart.”

The next morning I got five pesos together somehow and came running over. My aunt wasn’t ready. After greeting me she came out and said flatly that she wasn’t going to the hospital because she was afraid of dying, afraid that they would experiment with her body and would disembowel her. Actually, I felt a little relieved. I thought, “I’m not going to bother visiting her any more.”

On the following day, there I was with her again. This time everyone in the vecindad told me how Gaspar had beaten her up, so I spoke to her about moving over to my house.

“No, son, I won’t leave here until they carry me out, feet first.”

Then, about two weeks before my aunt died, my sister Consuelo came here from Nuevo Laredo, where she had taken Manuel’s children. She was trying to arrange for them to go to school across the border so she had to run all over the city getting the papers signed. Finally she got around to visiting my aunt.

“And how are you, little mother, so lovely, so precious….” She gave her a kiss, and the old woman greeted her with tears of pleasure. She was like that, always crying. So they kissed and hugged. When Consuelo found out my aunt was sick she immediately took charge and went with her to Dr. Ramón.

The next day my sister said to me, “Listen, Roberto, how barbarous you are, how inhuman, how useless!” She blamed me entirely for not taking care of our aunt. Why hadn’t I taken her to a doctor, why hadn’t I helped her, why this and why that?

She was probably right but I told her she shouldn’t talk like that because I was doing more for my aunt than anyone else. “You! You haven’t tried anything,” she replied. She had Dr. Ramón’s prescription filled and after several days went by she said, “This medicine is not doing any good. I think we are going to have to take her to Dr. Santoyo.”

“Caray, sister, Santoyo charged twenty-five pesos for an office call and fifty if he comes to the house and I don’t have any money right now.”

“Well then,” she said, “here are the twenty-five pesos for the doctor.”

“All right,” I said. “I’ll do it.”

That day turned out to be a very bad one in the plaza. I didn’t earn a cent and there was no food at home. We didn’t even have milk for the baby and had to give him rice water with sugar. So I felt obliged that evening to use ten pesos from Conseulo’s twenty-five for milk, bread, and rice. At night a neighbor of mine came over and I said to him, “I have a little problem. Could you lend me ten pesos until Saturday?”

“Yes, of course, señor Roberto, here you are.” So the next day I took my Aunt Guadalupe to Dr. Santoyo. We had to go by bus because there wasn’t enough money for anything else. I said, “Look, old woman, forgive me, I know that the bus shakes you up, but do you think you can stand it?”

“Yes, yes, let’s go, boy,” she said, “as long as I get there.” So we went. There were two or three patients ahead of us, and as there was a chapel in the clinic on the floor above I took my aunt upstairs and we both prayed a while together. It was nice there and my aunt felt better after asking her favors. Then we went back and waited for our turn.

The examination took only about five minutes. When my aunt came out, she told me, “Look, he gave me this medicine, a salve.” Actually, the salve was for hemorrhoids. I know because Dr. Santoyo had prescribed the same thing for my wife. The doctor, who was behind me, whispered, “Cancer. Tomorrow go to the General Hospital. You can find me in ward thirteen.”

The next day Gaspar and my aunt went to the hospital alone. When they got there they sent them all over and told them to come back the next day.

The next day I took my aunt back again. Gaspar came with us. All that happened was that a nurse wrote down information about my aunt’s symptoms.

“Ay, that old nurse is mean,” my aunt said. “She speaks roughly to me. ‘Stand here,’ she says, ‘go over there. Don’t shake so much.’ It’s like an ice box in there. I felt like a seltzer bottle that had been put into a regrigerator. My fingers were twisted with the cold. Would God have put us into the world and not expected us to shake when it was cold?”

“Ay, Díos mío,” I thought to myself, “why do we have to put up with such misery?” To my aunt I said, “Ah, it’s the people who don’t have any money who get this kind of treatment. But don’t worry, if that nurse says anything tomorrow you can tell her where to go.” I just wanted my aunt to know that I was backing her up all the time.

They did nothing for her there at the hospital, absolutely nothing. They made her waste her time miserably and spend money that she didn’t have. My aunt had advanced intestinal cancer, and it was incurable.

On November 1, All Souls Day, I had earned very little money, only six pesos, and I went to her house and saw everything so wretched, so pitiable, and—ay, it tears my heart when I remember this. How I wanted things to be different! My wife, my son and I at least had beans to eat, but the poverty of my aunt! I told her, “Caray, aunt, this was a very bad day for me. I made practically nothing. But look, take two pesos and I’ll use the rest to buy milk for the boy.” I wasn’t telling her the truth, because milk costs fourteen pesos a bottle and I only had four left. Then she said, “Ay, son, don’t worry about me. You must give it to your son and to Andrea.” I told her they had plenty to eat so she accepted the two pesos.

“Good-bye, and God bless you, and Martincito de Porres, the Holy señor of Chalma….” She always commended me to all the saints, and perhaps they have helped me more than once. I left in despair, saying to myself, “She is going to die, I know it for sure. I don’t think she’ll last out the year.”

On Saturday, the 2nd of November at about ten in the morning I went to my brother’s house. I had some porcelain figurines I had given my wife, two little dogs and a cat, which Manuel had bought at a bargain. And I was taking them to the plaza to sell. I went to my brother and said, “Shall we go to the plaza? I’ll go ahead because I want to sell these, and you know it’s best to get there early.”

“Yes, hombre, you go ahead and I’ll catch up.”

I had no more than walked to the market, greeted some friends, and set out my wares, when my sister-in-law María came up and said, “Listen, Roberto, you’d better go to your aunt’s house in a hurry because she’s bleeding all over and is very bad.”

A woman stopped to look at the figurines.

“Come on,” María said, “run, hurry.”

“Wait a minute,” said the customer. What is the least you will take for these?”

“Give me a peso for everything. You can see what a bargain you’re getting.”

“All right, it’s a deal. Now go ahead.” And I ran, leaving María far behind.

I reached the door of my aunt’s house and found my brother there. I went in and saw her. It was a very sad sight because she had died in much pain and in a way more wretched than the deaths of any other members of my family that I can remember. She was stretched out, face down.

I went over and touched her chest. She was very cold and I began to tremble. I could imagine the desperation she must have felt at the hour of her death. And I said, “Caramba, brother, look, here is the last of the Vélezes.”

I felt like crying, but I couldn’t.

“Ah, thank God she is at rest,” I said. I had asked God to heal my aunt, but that if it were His will to take her, that He would not let her suffer very much. And just look how quickly she has died. “What shall we do now? I only have forty centavos in my pocket.”

“Yes, what shall we do?” Manuel asked. “Who’s going to take charge of all this?”

“I will, brother, who else?” Then I asked him for five pesos and hurried to my godmother’s house to see if she would lend me some money. But when I got there, my godmother had just gone to pay us a visit, so I left a message for her and went back to the Panaderos vecindad.

By this time someone had picked my aunt up off the floor and laid her on the bed. They had cleaned off the blood, and a woman, one of those old hags, had mopped the blood off the floor so that it looked a little cleaner.

My brother left to see about the funeral and in a little while my wife and my godmother arrived, bringing my son with them.

“Don’t come in, Andrea,” I said, “because it might harm the boy.”

“Ay, whatever you say.”

“What happened, Roberto?” asked my godmother.

“What do you think, godmother? The last one left to me of my mother’s family has gone. And, look, now we need money for the burial.”

“I brought only 100 pesos with me,” she said, “but I have another 150 pesos at home.” I accepted the loan of 250 pesos, but I told her, “Look, I don’t expect to have any money until December, and I’m not sure of that yet.”

“What about your brother?”

“All the poor fellow has right now is ten or fifteen pesos in his pocket. So what are we going to do?”

“At least you have the 250 pesos. Here are 100, and I’ll go home right now and bring the other 150.” When she left I said to my wife, “Look, Andrea, here are 70 pesos. Take the boy to Dr. Ramón and buy the milk and whatever else you need. And send a telegram to my sister Consuelo.” I wondered if we should also notify my sister Marta in Acapulco, but I decided that with all those small children she wouldn’t be able to come anyway, and the news would only make her unhappy.

By this time my aunt was already in the coffin. When Gaspar returned from the hospital, where he had been to get the death certificate, I said, “Hombre, what happened? Who brought this?”

“I did, señor Roberto,” he said. “It was the cheapest one I could find. At first the fellow at the Burial Agency wanted six hundred pesos for the complete service, with a hearse and a bus and everything, but I told him, ‘Six hundred! Excuse me, but I haven’t got that kind of money. It’s a lot for a man like me. I’m going where it will be cheaper.’ So he called me back and said, ‘All right, seeing it’s you, I’ll do it for four hundred.’ ”

Gaspar began to cry. That man was always crying! It made me angry. Honestly, I felt it wasn’t the man who was crying but the hypocrite.

“Calm down, Gaspar, I feel her loss more deeply than you and I feel like crying too. But you don’t gain anything by crying. What we have to do is get things done.”

“Well, I brought the coffin,” he said.

“Did you pay something down?”

“No. They told me at the Agency that as I was so poor they would give me until Monday to get the money together.”

“It is Saturday now—three days of mourning for my aunt. All right, 400 pesos is less than I expected.”

Matilde and Pancho had offered to take up a collection among the news vendors. At about seven o’clock Pancho’s sister came in and I said to her, “Will you do me a favor? Go buy me some flowers and some candles for my aunt.”

“Yes, gladly.” I gave her thirty pesos and she brought me back sixty centavos in change because the flowers and candles cost twenty-nine pesos and forty centavos. I waited for Matilde’s return to give her money to buy coffee, sugar, bread and charcoal and to get some chinchol to spike the coffee for the mourners.

By nighttime, we were ready to begin the wake.

Consuelo:

“Señorita Consuelo Sánchez, Avenida del Sol, Nuevo Laredo.” The telegram was short: “Come by plane if you can. Aunt Guadalupe died this morning.”

You cannot imagine the shock it gave me. I had expected this blow, but I had trusted that when it came I would be there in time to say goodbye. After I read the telegram several times I sat down at my beloved typewriter. Usually it comforts me; it is the thing that brings self-respect and order to my life. But now I felt depressed, rejected, vastly alone. Two days before, on November 1, All Soul’s Day, when I took my four nieces and nephews to church, I had knelt before the altar and had begged Christ to let me see my aunt before her end came. Then I looked directly at Saint Martin on his marble pedestal surrounded by lighted candles and I said to him, “Brother Martin of Porres, if it is true that you can perform miracles, I challenge you to heal my aunt—overnight. That is the only thing that will make me believe in you.”

Saint Martin didn’t take up my challenge and now I scolded him, “You are bad. I don’t love you. You revenged yourself. Why? Why? I prayed so hard.”

What can I say to express the pain that has drained away the last drop of joy from my heart? I have never been able to accept death the way it comes to people in my class. We are all going to die, yes, but why in such inhuman, miserable conditions? I’ve always thought there was no need for the poor to die like that. Their struggle is so tremendous…so titanic…no, no, it isn’t fair. I refuse to resign myself to death in that tragic form.

There are authors who have written that the Mexican cares nothing about life and knows how to face death. There are jokes and sayings and songs about it but I would like to see those famous writers in our place, undergoing the terrible, hideous sufferings we do, and then see if they are able to accept the death of any one of us with a smile on their lips. It’s all a big lie. The way I see it, there’s nothing charming about death nor is it something we have become accustomed to because we celebrate fiestas for the dead or because we eat candy skulls or play with toy skeletons.

Maybe the older generation did have a philosophy of not attaching great importance to death but I believe that was the result of the suppression they were subjected to by the church. The church condemned them in their own minds by making them believe they were worthless and that they could achieve nothing here on earth, that they would get their reward in eternity. Their minds were completely crushed and they had no hopes or illusions of any kind. I mean to say they were dead while still alive.

Life holds no pleasure for me anymore. I expect nothing here in my tierra, my own land. Why do we insist on carrying on that absurd masquerade, the gigantic lie that hides the real truth here in this “republic” of Mexico? “We, the Mexicans,” amid “this prospering beauty with its politically strong, economically solid foundation….” Oh, yes, we are making progress. We are advancing in technology and science; the steel structures are rising over the corpses. Everybody knows that the peasants and the poor in the cities are being killed by starvation or other means…that they are being weakened. An entire generation is disappearing in an unforgivable fashion. I can no longer bear to see how they are humiliated and how they die.

Now my viejita, my little old lady, is dead. She had lived in a humble little nest full of lice, rats, filth and garbage, hidden among the folds of the formal gown of that elegant lady, Mexico City. In that “solid foundation” my aunt ate, slept, loved, and suffered. She swept the yard every day at six in the morning for fifteen pesos a month, unplugged the drains of the vecindad for two pesos more and washed a dozen pieces of laundry for three. For three times eight cents, North American, she kneeled at the washtub from seven in the morning until six at night. Besides all this, to be sure of something to eat, she would go from neighbor to neighbor minding the children for a mother who had just given birth, washing dishes and diapers, or scraping floors with steel wool and sandpaper, in return for which she might receive a taco which she would share with her compañero, Gaspar or with some other hungry person. She even managed to find something to feed her dog.

It would have been absurd to call her “saint” but that’s what she was. So gentle, so kind, so meek…she was incapable of insubordination to her masters, even to ask for the help to which she had a right. She was always ready to obey, always ready to serve. She revered the designs of God, unquestioningly following His commandments. Saints become saints because of their suffering. Well, she suffered martyrdom from the time they named her Guadalupe. Mexico, how can I love you when you devour those as defenseless as she?

Now we are free of that burden. She who was born “when the peaches were ripe…in the year…figure out how long ago it was, old man,” she would say to my uncle. She who travelled with the guerrillas in the revolution, washing and ironing for “my General with the earring, my General Angeles…he was very particular.” She, the last link to our dead mother, is now gone, slipping away from the edge of our lives along which she had passed on tiptoe.

I rested my head on the typewriter for a long time. The children paid no attention to me. They didn’t even notice that I was upset. Poor little orphans! They suffered so much to get so little. Knowing what future their lives would take if they were left in their father’s house, I brought them back to Nuevo Laredo with me. So there were four others to share my meager typist’s earnings. How I wanted to help them have a better life and how difficult it has been!

I thought of how badly my brothers had behaved toward my aunt, she who had given Manuel a home when he had married his first wife and who had taken in Roberto from prison when our father would not touch him. Two weeks before, in Mexico City, I had asked Roberto very specially to write me about her. That was after I had taken her to the doctor who said she needed an operation and analysis to find out whether she had cancer. I was angry with everyone for not telling me sooner, for waiting until everything was over.

It was Sunday and the bank was closed so I borrowed money from a neighbor for my ticket and a telegram: “Leaving by bus at two. Meet me.” It was not until Mariquita saw me folding my black dress into my suitcase that she asked, “Are you leaving, aunt?”

“Yes, can’t you see that I’m packing?” I was angry with the children for not even asking what had happened, so I didn’t bother to tell them why I was going away. I gave them the 125 pesos for the week’s expenses and warned them, “Be very careful. I don’t want to find any accidents when I come back. You know that you have to lock up at night and not let anyone in. Nobody has permission to go anywhere. Mariquita, if you can prepare breakfast and dinner and get to school, go; if not, let them know you’ll be absent—or figure out yourself what to do. I don’t want any more problems.”

I put on my makeup carefully and took my full-length red coat. I wore my dark glasses for I was barely able to keep from sobbing. I waited for the bus to leave and finally it pulled out at 2:45.

Along the way, I felt as though I were suffocating. Fortunately my neighbor, a young man, started a conversation with me. He looked a few years younger than I, about twenty-two, or so.

“On a vacation?”

“Yes.”

“For pleasure?”

“Yes, for pleasure.”

I talked with him gladly although I had to turn towards the window now and then to free a tear. We introduced ourselves. He was a law student in his second year at the university. When I heard he was from the north of Mexico I was relieved. Northerners are more reliable and they treat women better. By the time we arrived in Monterrey we were friends. He invited me for a cup of coffee and I accepted. I didn’t care what I did; the important thing was to distract myself from my thoughts.

Finally my neighbor went to sleep and I let the tears come pouring down my cheeks unchecked. I couldn’t get my aunt out of my mind. I reproached myself a thousand times for not having written to her. I had no money to send and I always imagined the moment when she would open the envelope and find it empty. And when I had a little money, I thought that if I sent it, she’d use it for drink. I also felt hurt because she didn’t want to come and live with me in Nuevo Laredo. I was continually asking her because I needed her. But the last time I saw her I had consoled myself with the thought that she felt close to her compañero, Gaspar, and mentally I thanked him. “At least she is not alone,” I thought. I stood before her and said, “Give me your blessing, little mother. I’m leaving now, but we’ll see each other soon.” She made the sign of the cross over my head and kissed me on the cheek…the sweetest, softest kiss. I think it was the first and only time that she did a thing like that to me. I gave her twenty pesos which she put in the bosom of her dress and I turned and left quickly.

Just two weeks later, here I was, rushing to accompany her to her last resting place! I felt a hard bar of pain across my temples and I began to hiccup in silent spasms. My neighbor’s hand timidly brushed my fingers and I thought to myself, “The Mexican man! I need to get married…a companion is necessary at times like these…here I am, so alone, and so in need….” My eyes moved along the faintly-lighted narrow aisle of the bus as I repeated to myself, “Alone….” I thought of Jaime, whom I had loved but could not respect, of Mario, whom I did not love, but ran off with, to revenge myself on my father…. The man next to me kept up the gentle pressure on my hand. “I mustn’t forget where I’m going…but I don’t want to think, to suffer any more. I wonder why life is so unhappy, especially for those of us who have nothing.” My neighbor leaned over and kissed my cheek. It was the tiniest of kisses. I looked at him out of the corner of my eye, “Hmm, now you’ve made the test,” I thought to myself. “I know what you want and where you’re heading. You can’t fool me with your gentlemanly gestures.” On the next try I put my hand between his mouth and my cheek and said, “Can’t you sleep?”

He offered me a cigarette. I accepted with thanks. It gave me a chance to let some of my grief out in puffs of smoke instead of in sobs. The fact that he was aware of my troubles made things a little easier.

“You know what?” I confided. “What I told you this afternoon is not true. I’m not on vacation. I’m going to my aunt’s funeral. She was my only relative on my mother’s side. Now the whole family is gone.” Even though I felt hesitant about talking, I began telling the whole story.

We continued conversing a long time. He told me about his grandmother who was very sweet. He spoke of the differences in character between himself and his friends at the university, of how he admired the prudence and good conduct of girls like the ones who worked at Sears and Sanborn’s, and about the parties he goes to, where he behaves frankly and openly like a northerner without caring what others will say. Each of us discussed our social contacts in Mexico City. Finally we stopped talking and I rested my head against the left side of my seat. After a few minutes he kissed me again on the cheek. I pushed him away but before I knew it his lips were on mine. I pushed him back harder thinking, “That is as far as you are going to get.” I drew quite a distance away and remained with my back turned to him until my leg fell asleep. Then he said, “Why don’t you lean against my shoulder?” I rested my head on his shoulder, prepared to jerk it away if he annoyed me again, but he didn’t and soon he was asleep himself.

At the next stop my friend invited me to have supper. He made some jokes at which I laughed and by the time we got back on the bus he had become “my faithful servant.” He continued discussing a law suit he was working on. Like many law students he was already acting like a lawyer, taking on their mannerisms and personality ahead of time. I smiled at his presumption and said, “Pardon me, I’m just a plain stenographer.” He seemed to get the idea and stopped pushing his lawyer’s shingle into my face.

Finally, everybody was asleep and the bus was silent. I was the only one watching the road. The driver’s manuevers were like a bull fighter’s passes when he went by trailer trucks on curves and wove in and out of lanes with cars coming from both directions.

We entered the State of Mexico and my companion got off at Tlanepantla. Before he left, he wrote his address in my address book and said, “Write me.”

“Of course,” I said.

It was after eight a.m. when we pulled into the terminal. I had no strength to carry my suitcase. I did not want to get to my destination. I felt cowardly.

I got a taxi and told the driver to take me to No. 33 Street of the Bakers. He seemed surprised at the address I gave him and kept trying to find out where I came from, but I was crying and couldn’t speak. He said, “You must be bearing a load of grief, to be coming crying like this.” That small drop was all I needed for my cup to overflow. So I told him what I had come for and his sympathy gave me strength to get to my destination.

II

THE WAKE

Roberto:

My aunt’s associates were the very poorest—bums, drunks, old hags, thieves, chinchol– and pulque-drinkers and they were all at the wake. The women wore clothes that were patches on top of patches, and even then their skin showed through. Each one who came into the room covered her head with her shawl or whatever piece of cloth she had brought. They came, heard the account of my Aunt Guadalupe’s death, crossed themselves, prayed an Our Father and an Ave Maria and left. And as they left, “Hombre, here, I don’t have any more but take it,” and they gave me some money, a five, a twenty, a half peso, a few centavos. It meant taking a glass of aguardiente from their mouths, but they left their pennies for the old lady who had sheltered them in her little house. This tore at my heart. We didn’t get much from them but I saw their sincerity.

It was my unpleasant duty to tell my father the news. I called him on the phone and said, “Imagine, papá, what has happened. My aunt has died.”

“Ay, caray,” he said, “look at the situation I am in, so far behind….” And he began to tell me his troubles. I saw that I couldn’t ask him for help because he was very pressed for money himself. Before he hung up he said, “If I get over there in the afternoon I’ll see what I can do.”

“That’s fine, papá,” I said. I doubted that he’d come. I don’t remember when my father has ever visited my aunt’s house.

I went back and that bastard Gaspar was there. “Have you eaten?” I asked him.

“No, Roberto, but I’m not hungry. What I want most is my old woman. My pretty little mother is gone. The people here say that I finished her off, but who should know better than you what really happened? I never struck my old woman.” His words sounded so sincere that for a moment I felt sympathy for him. “Gaspar,” I said, “take this peso and buy me some cigarettes, and get some for yourself.”

While I waited I went over to a little grocery store and bought some bread and cheese and made myself a sandwich.

Gaspar returned drunk. Instead of buying the cigarettes he went and bought a peso’s worth of alcohol.

“Hombre, Gaspar, please show some respect for the body of my aunt.”

“Yes, señor Roberto, whatever you say.” He calmed down for a little while, then he started saying, “What do you all want? When she was alive no one came to visit her, and now everyone is here crying. Bastards, hypocrites, go to hell!”

“Don’t pay any attention,” I told them. “He feels the death of my aunt, though not so much as I do, and besides he has been drinking.” After a while he started in on me.

“No one gives orders here except me,” he said. “This is my house.”

“All right, Gaspar, all right, it’s yours for the moment, but once my aunt is buried with proper respect, you’ll have to get your things together and be on your way, because you have absolutely nothing here. This is not your house and never will be.”

“Now we see who’s giving the orders around here. My queenie newly dead and already you people are sharpening your claws. You’re all like vultures, waiting for it to be over so you can take her things.”

“Look,” I said, “you’re offending the corpse. You’re showing no respect. Now it’s up to me to get you out of here,” and I grabbed him by his clothes and took him outside. I propped him against the wall and sat down where I could keep an eye on him. I was fed up with the guy but my grief was deeper than my anger. At that moment my only aim was to give the last member of my mother’s family a decent burial. I watched the little procession of visitors that came and went through the door. I felt content that my aunt had her mourners, her flowers, and her candles.

Manuel:

Inside the narrow room was the open coffin. It was just a large box lined with cheap gray cloth. On the thin pillow filled with sawdust, under the sad yellow light of a small bulb hung directly above it, my aunt’s wrinkled face looked sick with use and neglect, and with a kind of boredom. Poor little old woman! Her eyes were slightly open and her toothless mouth was nothing but a black hole that seemed to be mocking us. The veins on her yellow-green forehead bulged and I could clearly see the bruise she received on her left cheekbone when she fell.

There was a wreath of lilies and four candlesticks, one at each corner of the coffin. The tiny flames of the candles flickered as if they were burning against their will. Beside each candlestick stood four men, all poorly dressed, with sad faces and folded arms. This was the guard of honor, the last homage given to my aunt by her humble friends. They looked like characters from the court of miracles.

A few women, who smelled strongly of alcohol, squatted in the tiny space inside the kitchen door, some dozing and others talking in low voices.

Outside, Gaspar was listening and shaking his head.

What a wake! That wake was something in itself just because of the kind of people who were there. Most of them were down-and-out drunkards who came because they were driven by necessity. They are a very special kind of people who live in a way that’s hard to describe. I don’t want to sound like a politician but they belonged to a Mexico that is disappearing.

Finally it all began to get on my nerves, and I said to Roberto, “Listen, brother, I think I’ll go now,” and Maria and I went home.

The next day, Sunday, I was out in the market at eight-thirty in the morning. I had a hundred figurines in a carton and was anxious to get rid of them as fast as possible. As the market began to fill up with shouts and people, I peddled them at the top of my lungs: “Figurines, one peso each, get your figurines…why pay three pesos downtown?…get them for the living room, the dining room, the kitchen. Bring a little present to your sweetheart, your mamá, your wife…only a peso, while they last.”

Slowly my carton emptied. As I walked to my aunt’s house I met Pancho and Matilde, who were looking for me.

“Look, señor Manuel, we collected a little money from Pancho’s friends. And we were thinking that you have a lot of friends here too, so why don’t you take up a collection?”

They handed me an empty shoe box and the death certificate. That left me with no choice but to face the bull.

“Say, Shorty, how about giving a hand to help me bury my aunt?”

“Sure, brother. Hey, pitch in for this buddy here, his aunt died and he has to bury her.”

Everybody put his hand into his cash box and peso by peso I managed to get together a little pile. Frankly, it embarrassed me, and I didn’t ask everybody or I would have collected a lot more. Finally I got to my aunt’s house and handed over about a hundred pesos to Roberto.

“Hi, mano, did you make up the amount?” I asked.

“No, not yet. I had to take some out for flowers and for this and that….”

“Yaaa! What did you spend so much on?” Before I could stop myself I had shown my mistrust. My brother almost got sore, but he said, “Well, I took some things out of hock that were going to be lost.”

“Oh, no wonder. You did right. It doesn’t matter, I have some more here. What time are they coming for her?”

“Well…we were supposed to have paid up by twelve o’clock, and since it wasn’t possible now the funeral won’t be until tomorrow.”

And so we had to sit up with my aunt all Sunday night, too.

At nine o’clock Roberto went off to my room in the Casa Grande, leaving me his overcoat. The hours went by monotonously in silence. The five or six people who were still there no longer spoke and just drowsed. Suddenly there was a loud thud on the floor inside. Gaspar had tried to stretch himself out on three chairs that were near the coffin, but he was so drunk that he fell off, cutting his head, sending the candles flying and nearly knocking over the casket. As I helped him up, I said, “Gaspar, man, be careful! You cut your head! Laura, please, I brought a bottle of alcohol, would you see if you can find it so I can put some on this man’s cut?”

She found the bottle, and it was empty. She gestured that Gaspar had already disposed of the alcohol…inside him. So I washed the cut with a little tequila. After that he spread some rags on the floor and, giving the coffin a goodnight kiss, he stretched out and went to sleep.

At around two or three in the morning, my eyes began to close. I felt the night and the silence like a weight on my head and shoulders, pressing me down into the bench where I was sitting. After another hour of it I went home with my wife and woke my brother.

“It’s a good thing you woke me,” he said when I told him the time. “Consuelo is arriving at five and I have to go meet her.”

“Consuelo is coming?”

“Yes, didn’t you know?”

My brother went off to the bus station to wait for Skinny and I got into bed. That blasted Skinny! Coming all the way from Laredo!

(This is the first of two parts. Part II will appear in the next issue.)

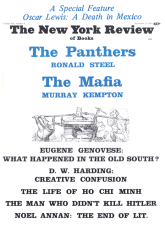

This Issue

September 11, 1969

-

*

The youngest daughter Marta was not in Mexico City and did not attend the funeral.

↩