Seaman Patrick N. Park, on the night of August 4, 1964, was directing the gun-control radar of the USS Maddox. For three hours he had heard torpedo reports from the ship’s sonarman, and he had seen, two or three times, the flash of guns from a nearby destroyer, the Turner Joy, in the rainy darkness. But his radar could find no targets, “only the occasional roll of a wave as it breaks into a whitecap.” At last, just before midnight, a target: “a damned big one, right on us…about 1,500 yards off the side, a nice fat blip.” He was ordered to open fire; luckily, however, not all seamen blindly follow orders.

Just before I pushed the trigger I suddenly realized, That’s the Turner Joy…. There was a lot of yelling of “Goddamn” back and forth, with the bridge telling me to “fire before we lose contact,” and me yelling right back at them…. I finally told them, “I’m not opening fire until I know where the Turner Joy is.” The bridge got on the phone and said, “Turn on your lights, Turner Joy.” Sure enough, there she was, right in the cross hairs… 1,500 yards away. If I had fired, it would have blown it clean out of the water. In fact, I could have been shot for not squeezing the trigger. Then people started asking, “What are we shooting at…?” We all began calming down. The whole thing seemed to end then.

Goulden’s fascinating book, which has gathered much new information about the Tonkin Gulf incidents, see: the experience of Patrick Park as, with one exception, a microcosm of the entire Tonkin affair—

illustrating the confusion between illusion and reality and the inclination of man to act upon facts as he anticipates they should be, rather than what rational examination shows them to be. The exception is that Park refused to squeeze the firing key, while Washington acted on the basis of assumption, not fact—hastily, precipitously, perhaps even unnecessarily—firing at an unseen enemy lurking behind the blackness of misinformation.

Not all will accept the analogy between Washington and a confused young seaman, but this hardly lessens the importance of Goulden’s patient researches. The author of a book on AT&T and a former reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, Goulden has made good use of his years of experience in Washington. He has not really written a “thesis” book; his method is to stick closely to official documents (above all the neglected Fulbright Committee Hearing of 1968)1 and first-hand interviews with witnesses the Committee failed to call, including Seaman Park. At times, he can be faulted for believing so much what was told him in the Pentagon. Even so, the result is devastating. It is now even more clear that the Tonkin Gulf Resolution (in his words) “contains the fatal taint of deception.” The Administration had withheld much vital information in formulating the simple story of “unprovoked attack” by which that resolution was pushed through Congress.

The Maddox, according to McNamara in 1964, was on a “routine patrol in international waters.” In fact it was on an electronics intelligence (ELINT) or spy mission for the National Security Agency and CIA. One of its many intelligence requirements orders was “to stimulate Chicom-North Vietnamese electronic reaction,” i.e., to provoke the North Vietnamese into turning on their defensive radars so that the frequencies could be measured. To this end, between August 1 and 4, the Maddox repeatedly simulated attacks by moving toward the shore with its gun control radar mechanism turned on, as if it were preparing to shoot at targets. In so doing, it violated the twelve-mile limit which Pentagon officials thought North Vietnam claimed for her territorial waters.2 Far from being “routine,” this was only the third such patrol in the Tonkin Gulf in thirty-two months; and the North Vietnamese had to assess it in the context of a recent US build-up and South Vietnamese threats to carry the war north.

On July 31, just before the patrol, the South Vietnamese had for the first time used American “swift boats” to bombard the North Vietnamese coast, attacking the islands of Hon Ngu and Hon Me. McNamara had claimed that the US Navy and the Maddox were “not aware of any South Vietnamese actions, if there were any”; but the ship’s cable traffic reveals frequent references to “34-Alpha Operations,” the Navy code name for these covert attacks. On July 25 in Taiwan the Maddox had taken aboard an NSA “Communications Van” (COMVAN) with its special complement of intelligence personnel and communications technicians; and some of the COMVAN team were able to intercept and interpret North Vietnamese ship-to-shore messages. Goulden reports that they heard North Vietnamese orders to position a defensive ring of PT boats around Hon Me after the first South Vietnamese attack on the North Vietnamese islands, as well as speculations about the possible link between the Maddox and the raids.

Advertisement

Near Hon Me on the morning of August 2 the NSA technicians intercepted orders for PT boats to attack the Maddox. Captain Herrick aboard the Maddox cabled to his superiors in Honolulu that “continuance of patrol presents an unacceptable risk,” but was ordered to resume his itinerary. The Maddox returned to a point eleven miles from Hon Me island, and then heard a North Vietnamese order for its attack. This was the prelude for the first incident of August 2—it is clear both that a North Vietnamese attack was ordered and that the Maddox fired the first shots. A North Vietnamese patrol boat was left “dead in water,” and another probably damaged. The Maddox then withdrew, having been dented by a single machine-gun bullet.

At this point the Maddox might have broken off the patrol permanently (after all, the original orders of the Joint Chiefs had warned about the risks from the stepped-up 34-A operations). Alternatively, it might have resumed the patrol as originally planned, along the entire 600-mile coastline of the Tonkin Gulf. The President’s decision was, without bombing North Vietnam, to send “that ship back up there” together with a second destroyer, the Turner Joy; but the admirals of the Pacific command in Honolulu translated this general order into a third, much more dangerous, course of action. The destroyers were ordered to modify the original patrol plan and to spend the next two days in a single 45-mile stretch (between Navy checkpoints “Charlie” and “Delta”) around the obviously sensitive island of Hon Me which had just been shelled by the South Vietnamese.

On August 3 Captain Herrick suggested termination of the patrol altogether, and Admiral Johnson (Seventh Fleet Commander) reported his intention to end it on the evening of August 4. (In this case the disputed second incident would never have arisen.) The on-scene commanders were however overruled by a second cable from Admiral Sharp, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific (CINCPAC), in Honolulu, which restricted the ships even more closely to the Hon Me area. Sharp specified that “the above patrol will…(b) possibly draw NVN PGMS [North Vietnamese patrol boats] to northward away from area of 34-A Ops.”

Sharp, in other words, hoped the destroyers might serve as decoys and distract North Vietnam’s small fleet of PT boats, leaving unimpeded the 34-A Operations to the south. (McNamara claimed that “every possible effort was made to keep these two operations separate,” and this may hold true for the efforts of Washington and the ship commanders, but not for Honolulu’s pre-occupation with Hon Me.3 ) After listening to further intercepts of the North Vietnamese radio (which in a strict sense he may not have been authorized to do), Captain Herrick aboard the Maddox spelled out more clearly in a cable to Honolulu the dangers of the Hon Me area:

A. Evaluation of info from various sources indicates that DRV [Democratic Republic of Vietnam, i.e., North Vietnam] considers patrol directly involved with 34-A ops. DRV considers United States ships present as enemies…and have already indicated readiness to treat us in that category.

B. DRV are very sensitive about Hon Me. Believe this is PT operating base, and the cove there presently contains numerous patrol and PT craft which have been repositioned from northerly bases.

Meanwhile the South Vietnamese had already (at 12:30 A.M. August 4) conducted a second series of 34-A raids some seventy miles southwest of the destroyers. McNamara admitted in 1968 that he was not informed of these second raids until after he and the President authorized the air strikes against North Vietnam. Nevertheless the facts were known to “some senior commanders above the level of the commanders of the task force”—a line of command consisting of Admirals Johnson, Moorer, and Sharp. Goulden asks why this essential information did not reach McNamara, who consulted Admiral Sharp about the air strikes by telephone.

Despite the raids, and the mounting nervousness on both sides, the daylight hours of August 4 were uneventful. The night was pitch dark from a cover of black storm clouds, and the sea and atmospheric conditions (as McNamara conceded) were such as to cause both radar and sonar to function erratically. It was in these murky circumstances that the alleged second incident (or “unprovoked attack”) took place. Unexplained radar blips at 36 miles northeast and an intercepted enemy message caused Captain Herrick to fear an imminent ambush at 7:40 P.M.; two hours later (if we accept a problematic Pentagon chronology), US ships opened fire at fresh radar contacts moving in from the west and south. A “torpedo wake” was then seen from aboard the Turner Joy (or more specifically a track in the fluorescent water that in the words of a viewer “wasn’t no porpoise”). In the course of this dark evening, there were also isolated reports of a column of smoke, a searchlight, gun flashes, cockpit lights, and a silhouetted boat. But most of these reports came from the Turner Joy, whose crew had never been under fire before and did most of the shooting.4 (Six weeks later, the inexperienced crew of the destroyer Edwards reported similar “sightings” of an attack—but these were rejected by an official naval board of inquiry.)

Advertisement

In 1964 McNamara told the Fulbright Committee how the ships then reported “that they were under continuous torpedo attack.” His account did not bother to mention a later cable from Herrick saying that “all subsequent Maddox torpedo reports [after the first] are doubtful in that it is suspected that sonarman was hearing ship’s own propeller beat.” (For some reason this cable from Herrick took three or more hours to reach Washington, arriving nineteen minutes after the planes had been launched against North Vietnam.) Soon after the Turner Joy cabled that its sonar had received no indications of torpedo noises, “even that which passed down side.” A reverse paradox occurred with the fire-control radars. The Turner Joy radar fixed on several targets. The Maddox nearby locked on only one; and that, as we have seen, was the Turner Joy. 5

There are other grounds for doubting the reality of the alleged August 4 attack. No radar or electronic activity was ever detected from the alleged attackers, raising doubts that they could have tracked the destroyers on such a dark night. The North Vietnamese promptly disclaimed any role in the second incident, while identifying certain South Vietnamese craft which they claimed had slipped out that evening from Danang. (Their denial was later sustained by an important and cooperative North Vietnamese prisoner-of-war, the second-in-command of the PT squadron in question, who supplied much other useful information to his American interrogators.)

Normally an incident of this sort involving so many uncertainties would be followed by a naval board of inquiry. Such a review followed the so-called “third” Tonkin Gulf incident of September 18, 1964. The board found that although two other US destroyers had held numerous radar “contacts,” had reported attack, had seen “tracer bullets” and “light flashes,” and in the end had fired some 300 rounds of ammunition, there had in fact been no North Vietnamese attack. The lack of any such inquiry into the August 4 incident is itself one further ground for suspicion.

Washington was not unaware of all this confusion when it ordered the retaliatory air strike. On the contrary Captain Herrick’s first expression of doubt had been relayed to Washington by the Naval Communications Station, Philippines, as early as 1:27 P.M. EDT, August 4 (or 1:27 A.M., August 5, in the Tonkin Gulf):

Review of action makes many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful…. Freak weather effects and over-eager sonarman may have accounted for many reports. No actual visual sightings by Maddox. Suggest complete evaluation before any further action.

But it was about this time that President Johnson had agreed in principle to an American reprisal, making it clear that he wanted more positive information before the reprisal attack was launched. McNamara’s testimony showed that for the next four and one-half hours there was confusion and debate over whether to proceed: “I personally called Admiral Sharp and…said we obviously do not want to carry out retaliatory action unless we are ‘damned sure what happened.’ “6 Certainty was restored, according to his account, by two corroborating sources.

The first was Admiral Sharp, who communicated many times with subordinate commanders, then phoned in at 5:23 “stating that he was convinced the attack had occurred and that all were satisfied it had.” If Sharp really said this, it was a gross misrepresentation. Herrick, according to the cables seen by the Committee staff, had merely confirmed the “apparent attempted ambush,” not the alleged attack two hours later. Some time after the strike order had been released, after 6:00 P.M. EDT, Herrick sent another cable which itemized his continuing doubts: for some reason this cable was not received in Washington until 10:59 P.M., when the retaliating airplanes were already airborne. At 11:00 the ship Turner Joy was again asked in an “urgent” cable for witnesses and evidence. Their reply indicated still further grounds for doubt.

McNamara’s second source of corroboration, the allegedly “unimpeachable” intercepts of North Vietnamese communications, deserves far more scrutiny than Goulden gives it. There were four groups of intercepts concerning the events of August 4, all of them supplied by the intelligence personnel aboard the Maddox to Herrick, to CINCPAC, and to Washington. The first two are credible, but do not prove an attack. The latter two, which if true would clearly confirm an attack, are both highly dubious, and not just because they both contain false information. McNamara chose to summarize the intercepts for the record:7

No. 1. Located the position of the Maddox and the Turner Joy.

No. 2. (Received Washington about 9:20 A.M.) Directed three vessels “to make ready for military operations.”

(It is unfortunate that Goulden twice—pp. 147, 207—echoes McNamara’s original characterization of this intercept as “North Vietnamese orders…to initiate the attack.” Senator Gore, who had just acquired the text, successfully challenged McNamara on precisely this point, and forced him to accept the more moderate phrasing.)8

No. 3. (Received Washington about 11:00 A.M.) Reported an American plane falling and ship wounded.

No. 4. (Received Washington “immediately after the attack ended,” i.e., just after 1:30 P.M.) Reported “that they had shot down two planes and sacrificed two ships,” and added further details.

The third and fourth groups, in other words, came in after the first highly excited flurry of cables from the American destroyers reporting attack. What made them so credible at the time is that in part they also echoed the cables: the Maddox had reported the disappearance of an unidentified aircraft from its screen, and the Turner Joy had reported sinking two enemy boats. Intercept group No. 4, which arrived in Washington in the crucial minutes right after Herrick’s expression of doubts, must have seemed like a clincher. As Herrick himself told Goulden in an interview, “We heard…their damage report confirm our assessment that two of the boats had been sunk.” It must have had an equal impact on McNamara, who has stated that his own decision at 6:07 P.M. to go ahead with the strike order was based particularly on “the communications intelligence.”

Nevertheless, as Goulden points out, Herrick at the time was not completely convinced by the last intercept, and for four and one-half hours McNamara was not either. What is more important: by evening (Washington time) the Turner Joy was no longer certain it had sunk two vessels; and in retrospect the grounds for believing so seem suspect. The Turner Joy had seen a “target” disappear from its radars, supposedly accounting for one ship, and some personnel thought they had seen a column of black smoke, supposedly accounting for another. But the radars were disturbed by atmospheric conditions that night and it was “dark as hell.” Goulden himself doubts that these bits of evidence prove anything and he quotes without challenging it the conclusion of a high-level Pentagon informant that “the so-called second attack of August 4 never took place.”

If this informant is correct, the similarity between the destroyer’s cables and the last intercepts is no longer corroborative, but highly suspicious. It is made all the more suspicious by the absence thus far of any credible evidence that US aircraft were damaged or missing.9 How, then, are we to explain the strange circumstance that a North Vietnamese “intercept” reported information which echoed the cables sent by the Maddox and the Turner Joy but which later turned out to have no convincing basis in fact? One possible explanation is that the North Vietnamese did, in fact, radio the news that two of their ships were lost, but somehow did so in error. It is also possible that the shots fired by the Turner Joy somehow struck two North Vietnamese ships. Both possibilities seem remote ones, however, and in any case neither accounts for the reports about downed aircraft. A third possibility is that American technicians were subconsciously influenced by the destroyers’ cable traffic in their hearing or interpretation of the North Vietnamese messages; but it is difficult to imagine how such errors could have been consistently made in the case of both groups of intercepts. A fourth possibility should therefore be considered: that the intercept may deliberately have been fed in—or distorted in the process of translation or summary—by American intelligence personnel in order to end the fateful and unexpected indecision in Washington.10

This possibility is increased by another undisputed anomaly: the failure of either one of the destroyers to detect any electronic activity from North Vietnamese ships—whether radar or radio communication—after about 2:30 P.M. Tonkin time, or some six hours before the alleged incident. Under these circumstances it is not only hard to imagine how the North Vietnamese could have conducted an attack out at sea in the darkness, it is also hard to imagine the origins of the information in the third and fourth “intercepts.” Herrick confirmed to Goulden what the Fulbright Committee had already learned, that “We had no radio contact, or heard no communications going on between the PT boats” (p. 153). As Goulden quite properly asks:

The communication van’s ability to intercept North Vietnamese messages had been amply demonstrated during the preceding four days; why, then, no intercepts from the PT boats during the August 4 incident? Messages from director ships, or a headquarters on Hon Me, which were audible to the North Vietnamese would also have been audible to the Maddox’s monitors—yet Herrick avows none were heard during the engagement. What, then, was the origin of the damage report?11

If such grave suspicions about the performance of our intelligence network are unfounded, there is much that can be done to put them at rest. The intercepts should be made public, both in their original form and as characterized at the time in intelligence reports. Investigation should be made to determine whether anything happened to US aircraft on that day which would have led the North Vietnamese to think they had shot down two planes. Even the disclosure of an honest error would serve, at this point, to clear the air rather than to poison it.12

In January 1968 Ambassador Goldberg, in presenting the American version of the Pueblo incident to the UN Security Council, did not hesitate to quote directly from intercepts of North Korean PT-boat communications which were only three days old. Yet one month later McNamara would not even discuss the North Vietnamese intercepts with the Fulbright Committee until its staff adviser (who had received the appropriate clearance when in the Navy) had been cleared from the room. Such furtiveness, until it has been explained, only deepens the credibility gap.

McNamara’s dilemma of 1964 must be grasped. To doubt the existence of an attack on August 4 (as Goulden clearly does, though he is not explicit on this point) is to doubt the credibility of the intelligence network which “proved” there was one.13 And if one does not choose with McNamara to believe the “proof,” then there is much more to question in the lower echelons of our national security bureaucracy than Admiral Sharp’s evident eagerness to bomb North Vietnam. Sharp might well have been restrained by McNamara, had it not been for the performance of the intelligence community’s technicians who handled the intercepts.

Sooner or later, most discussions of the Tonkin Gulf incidents (including McNamara’s) return, if only to dismiss it, to the possibility of conspiracy. In fact two kinds of conspiracy have been hinted at, a conspiracy by the Administration, and a conspiracy against it. (Failure to distinguish between these has led to confused accounts in which McNamara appears simultaneously as villain and victim.) On the first point, there have been charges of deliberate provocation of the North Vietnamese, as when I. F. Stone in these pages neatly characterized the Tonkin Gulf incidents as a “question not just of decision-making in a crisis but of crisis-making to support a secretly pre-arranged decision.”14

We have already seen South Vietnam’s first bombardment raids against North Vietnam (at Hon Me Island) were followed by the Maddox’s persistent feints toward Hon Me Island two days later. In the preceding weeks Hanoi had been subjected to other new pressures. On July 19 General Khanh had made a major public appeal for a bac thien or march to the north, and on July 22 Marshal Ky revealed that CIA-trained commando operations against North Vietnam had been stepped up 40 percent since July 10.15 Goulden reveals that every one of these escalations (including Khanh’s calls for invasion) had been suggested and finally approved as parts of a “measured pressure” plan prepared by an inter-agency Vietnam Working Group appointed by Johnson and headed by William Sullivan, a forty-one-year-old Foreign Service Officer. (One of the Sullivan group’s working papers specifically mentioned the patrol boat base and radar station on Hon Me Island.)

Another Sullivan group proposal was for setting up the Navy’s Yankee Station at the mouth of the Tonkin Gulf, which was first used for naval air strikes against Laos in early June. In June the well-informed Aviation Week had underlined the importance of this “first US offensive military action since Korea.” It added ominously: “President Johnson apparently is awaiting public reaction to the Laos air strikes in this country and abroad before taking the next big step on the escalation scale.”16

All of these escalations were not conspiratorial in any legal sense but were duly authorized, as part of a secret policy approved by the President, to increase the pressure on North Vietnam. But the Tonkin Gulf incidents also suggest a concerted campaign of deception, not by those in power around the President, but of them by their subordinates. Goulden argues that the commanders in Honolulu should now explain why they did not, until too late, tell Washington of the August 4 34-A raids; and why Herrick’s obvious doubts about the incident were transformed along the line into a report that he was “satisfied” an attack had taken place.

Goulden also asks whether Washington was kept informed by CINPAC of the various North Vietnamese threats against the Maddox, and of Herrick’s warnings of danger. He was told (but could not confirm) that the White House did not hear of the intercepted North Vietnamese threats on August 1-2 until after the August 2 incident. Finally he asks about Honolulu’s alteration of Washington’s orders, to provide for repeated runs in toward the Hon Me area, and whether Washington was consulted about this. The Foreign Relations Committee should pursue these questions, especially since the August 4 strike decision was made, it is now known, “on the basis of CINCPAC recommendations.”17

There are many other questions for Admiral Sharp and the US Pacific Commanders. Why did Sharp not consult Washington before ordering the much larger aircraft-carrier Constellation to join the Ticonderoga in the Tonkin Gulf, barely in time to make the large-scale retaliation of August 4 possible?18 (Sharp later ordered the Enterprise north without consultation after the Pueblo incident; but President Johnson, now more experienced, overruled him.19 ) Why were the President’s instructions after the first incident, calling in his own words for “a combat air patrol over the destroyers,” not carried out? On August 4 Herrick complained specifically that near Hon Me a fifteen-minute reaction time for operating air cover was unacceptable: “Cover must be overhead and controlled by destroyers at all times.” Yet this request for what the President had already ordered was rejected by Admiral Moore of the Ticonderoga, who however promised his aircraft were ready for “launch and support on short notice.” Why then (according to the official Pentagon chronology) when Herrick cabled at 7:40 P.M. August 4 that an attack appeared “imminent,” were fighter aircraft not launched from the Ticonderoga until 56 minutes later, arriving at 9:08 P.M.?20

Such questions (there are still others) suggest there may be more to the Tonkin Gulf affair than confusion and precipitous reaction. Goulden criticizes the naval commanders severely; he does not however call for disclosure of the intercepts and the intelligence reports about them. One can understand his caution—there is little precedent for outside review of intelligence activities—but a review that stops short with Admiral Sharp and his colleagues is likely to prove frustrating. An inquiry will not accomplish much if it reveals that the Admirals violated only the spirit of Washington’s cautionary directives, and never the letter of them.

More important, there are many signs that the intelligence community, rather than Honolulu or the White House, was the prime source of the many “coincidences” which together led to Tonkin. Whatever the outcome of an inquiry into the implausible intercepts of August 4, it is clear that the involvement of intelligence agencies in creating a more aggressive Vietnam policy was a crucial one, and that it has been concealed from the public. McNamara, in the 1968 Hearings, admitted at one point that US military personnel in Vietnam had the power to “suggest” and “work out adjustments” to the “South Vietnamese” 34-A attacks.21 These personnel were members of the so-called “Studies and Operations Group,” reporting in theory to General Westmoreland, but in fact to the CIA. The CIA was likewise deeply involved in the counter-guerrilla activities against North Vietnam, expanded after the arrival in Saigon May 1 of Brig. Gen. William DePuy, ex-CIA Deputy Division Chief. Finally, the CIA’s cover operation in Taiwan, the US Naval Auxiliary Communications Center (NACC), worked hand in glove with the NSA in communications and electronics intelligence missions, such as that of the Maddox.

This is not said to launch a blanket attack against the CIA, some of whose personnel voiced in 1964 what were probably the strongest warnings within the Administration against an escalation in Vietnam. 22 But of all Johnson’s civilian advisers, the CIA’s John McCone was in early 1964 the most important advocate of expanding the war against North Vietnam. Here as elsewhere McCone, the proponent of a “forward” or “rollback” strategy against Communist territory, was pitted against McNamara, the spokesman of a militant strategy of “containment.” In 1963 the two men had divided bitterly over the issue of whether or not to mount a second Bay of Pigs against Cuba. As for the Far East, McNamara had in 1962 passionately opposed “McCone’s somewhat apocalyptic view that sooner or later a showdown with the Chinese Communists was inevitable.”23 Hilsman assures us that Rusk also was opposed to the CIA’s proposal in that year (supported by Ray Cline, the station chief in Taiwan) for a large-scale landing by Chiang on the Chinese mainland—“a sort of even grander Bay of Pigs.”24

In early 1964 the proposal to bomb North Vietnam was seen, even by its supporters in the Johnson Administration, to raise the risk of a showdown with Communist China. Here Johnson and McNamara found themselves in a difficult position that was rapidly becoming a dilemma. On the one hand the two men had agreed (at a crucial emergency meeting held only two days after Kennedy’s assassination) to an unconditional pledge of military support to South Vietnam.25 On the other hand neither man had any appetite for a major expanded air war. McNamara still wanted to prove the ability of US Army advisers to win a limited war without escalating it beyond recognition, and Johnson also showed grave reluctance to escalate even after his campaign and election as a “peace candidate.” Yet nothing in South Vietnam seemed to be going right. William Sullivan, the leader of the Vietnam Working Group, had worked closely with Harriman to achieve the 1962 “neutralization” of Laos; now he was slowly converted to the view that the Johnson policy of doing “whatever is necessary” might lead in the end to bombing North Vietnam.

After a joint survey mission to Vietnam in March, McNamara still believed that the war must be won within South Vietnam itself. McCone, on the other hand, is reported to have recommended “that North Vietnam be bombed immediately and that the Nationalist Chinese Army be invited to enter the war.”26 Johnson wanted the two men to rethink their positions toward a consensus; but the gap was too great. Sullivan’s working group had been set up in December as a compromise between the two positions (to develop a list of bombing targets—thus postponing the decision on bombing, but also increasing its likelihood).

The plan of gradually increasing pressure against North Vietnam which Sullivan’s group now produced represented a similar effort to steer a “middle” course. The multistage scenario began with hints and warnings, such as sending unmarked jets to create sonic booms over Hanoi, to be followed by the establishment of the Navy’s Yankee Station, frequent feints at the shore by destroyers, and South Vietnamese torpedo boat raids.27 It would climax with a policy of selected “tit-for-tat” or “punch-for-punch” bombing reprisals28 which would hit in the end against Hanoi and Haiphong proper.

This was the consensus “package,” but it failed to resolve the debate. On the one hand (according to a well-informed right-wing source) the Joint Chiefs of Staff recommended unanimously in March that America “attempt to force the Communists to desist from their aggression by punishing their homeland.”29 On the other hand, Goulden (p. 91) agrees with other reports that from March through May Johnson was unwilling to buy the Sullivan compromise:

Persons who watched him that spring concluded that he was stalling; that when suddenly brought against the hard decisions required to implement his broad policy goal, he was not so confident it was worth the effort.

As a result the tension within the Administration began to increase. Elaborate contingency plans for “rollback” were planned, and discussed with allies. US Navy personnel and the CIA began to train South Vietnamese for the 34-A Operations Plan. But none of these plans had yet been authorized by the President. Meanwhile this uncertainty about American intentions was seen within the Administration as a prime cause of the growing political instability and neutralist sentiment in Saigon. This instability was increased by the many calls in July for a new Geneva Conference (U Thant was to report on such matters to Johnson on August 6), and led to reports of a possible coup in Saigon at the time of the second Tonkin Gulf incident.30 Within the Administration, the growing risk of neutralism in Saigon became a prime argument for carrying the war north.31

Frustrated in early 1964, the advocates of bombing looked outside the Administration to spokesmen like Dodd and Goldwater for public support: in April (long before Khanh had joined the cry) Richard Nixon called for US intervention, proclaiming that “the goal of the South Vietnamese army must be a free North Vietnam, and that the war must be carried north to achieve that goal.”32

The “freeing” of North Vietnam has never become a US policy objective. Nor was it contemplated by the Sullivan scenario, which specified that the United States should make it abundantly clear it had no intention of destroying or occupying North Vietnam. (Failure to make this clear, it was understood, would not only increase North Vietnamese resistance but might well provoke that direct confrontation with China which McCone thought inevitable. US Ambassador Kenneth Todd Young has written that recently one of the principal US themes in the Warsaw Ambassadorial talks with China has been that “the United States has no…intention of seeking to overthrow the Democratic Republic of North Vietnam.”33 ) Nevertheless former CIA hand William Bundy told a secret House Committee session in May that “rollback”—hitherto the slogan of right-wing propagandists like the American Security Council—was in fact a US strategic goal:

The objectives of our Far East policy are clear. They are, as they have been for many years under both parties, to preserve and strengthen the will and capacity of the peoples of the area to resist Communist aggression, and thus to produce a situation of strength from which we may in time see a rollback of Communist power.34

He is also reported to have told the Committee that the United States would drive the Communists from South Vietnam, even if it meant “attacking the countries [sic] to the north.”35 In the same month an article in Fortune, apparently based on leaks from the CIA, named China as “the true war base of the Communist offensive against South Vietnam,” and warned that the US might soon have to extend the war north. It cited “Western intelligence” as believing Russia had already told Hanoi it would stay out if a more forthright US intervention provoked the Chinese into a Korea-type response. (“Left to themselves, the Chinese could not cope with the totality of US forces.”36 )

At least as late as February 1965, according to Bernard Fall, one extreme faction in Washington held

that the Viet-Nam affair could be transformed into a “golden opportunity” to “solve” the Red Chinese problem as well, possibly by a Pan-Asian “crusade” involving Chinese Nationalist, Korean, and Japanese troops, backed by United States power as needed.37

The important top-level Honolulu Conference of June 1-2, 1964 (Rusk, McNamara, Taylor, McCone, Lodge, Sharp, and William Bundy) marked the beginning of the end of the “limited war” strategy so dear to Kennedy and McNamara. Reportedly this Conference agreed to a “forward strategy” against China (another slogan emanating from the right, in this case from the Foreign Policy Research Institute of Dr. Strausz-Hupé which has received support from a CIA “conduit” foundation) for CINCPAC in the whole of Southeast Asia.38

Soon after this Conference Johnson ratified for Laos the “punch-for-punch military policy” which he had previously refused to ratify for Vietnam. This included authorization for air strikes against Laos, and the readying of US bombers “to hit targets in North Vietnam and elsewhere if Washington gives the word.”39 He also authorized the various covert proposals of Sullivan which began in July, but he still postponed decision on the issue of bombing North Vietnam.

Laos, in other words, was the target offered, as a compromise, to the proponents of air strikes against North Vietnam. And it was the aircraft carriers which had been moved in for the purpose of striking Laos which made the strikes against North Vietnam, not yet authorized, possible at any moment. (In addition, the airfield at Danang had been secretly lengthened to handle jet F-100’s—despite their prohibition under the 1954 Geneva Agreements—and F-100’s had been brought in to fly strikes against Laos by June 21.)

Goulden fails to see how intimately events in Laos were linked to internal pressures on Johnson to escalate, for he unfortunately swallows the CIA version, which presents the right-wing Laotian coup of April 19, 1964 as a response to stepped-up Pathet Lao activity. (“In mid-April the Communist Pathet Lao mounted battalion-sized attacks against government positions, prompting a brief rightist overthrow of Premier Souvanna Phouma (a neutralist)”). In fact the chronology, and the causality, were the other way round: the fighting in the Plaine des Jarres was resumed in mid-May, after the coup had been followed by a new Army command of rightist generals who assumed command over the hitherto separate neutralist troops. As the pro-American correspondent Denis Warner confirms, the resulting “mass defections from the ranks of the neutralists…led to the rout of Kong Lae’s troops and the fall of the Plain of Jars.”40

In other words the right wing, not the Pathet Lao, provided by their coup the impetus which led to American escalation. The April 19 anti-neutralist coup in Vientiane, like Khanh’s anti-neutralist coup of January 30 in Saigon, was officially regretted in Washington. But both coups were spearheaded by pro-American figures (security chief Siho in Vientiane, Special Forces chief Nghiem in Saigon) whose offices and cadres had been set up by the CIA.41 It can be shown that Kennedy’s original escalations in Vietnam, like Johnson’s, followed US escalations in Laos, which were presented as responses to Communist provocations, but which in fact were originally triggered by actions of CIA personnel and their Asian cohorts. The air strikes after Tonkin, in other words, cannot be written off as an isolated instance of ill-advised judgment reached “hastily” and “precipitously” in Washington.

Goulden concludes with a review of the “mistakes seen in Tonkin.” Assuredly Washington made mistakes and, as Goulden demonstrates, they do “recur all too frequently.” One of his most telling chapters is a review of the command-and-control snafus surrounding other ill-fated electronics intelligence missions—the USS Liberty in the 1967 Israeli-Arab War, and more recently the Pueblo. The Israelis, he reveals, attacked the Liberty after the US military attaché, in good faith, had denied there were any US ships in the area. The attaché had seen a cable from the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordering all US craft in the area 100 miles out to sea; the Liberty however, had not received the order. The original message had been dispatched, in error, to the Philippines and then to Fort Meade in Maryland; a follow-up, confirming order was likewise deflected in error to Morocco.

Again Washington was thrown into a crisis of which it had no good intelligence. As McNamara later admitted, “I thought the Liberty had been attacked by Soviet forces. Thank goodness, our carrier commanders did not launch directly against the Soviet forces who were operating in the Mediterranean.” A warning message about the dangers inherent in the Pueblo’s mission was similarly misdirected. Goulden’s review underlines the dangers in thus shadowing the territorial waters of the world: at least 225 US personnel have been killed or captured in ELINT and other “ferret” missions since January 1950; and some of these incidents, like the Pueblo’s, have led not only to increased tension but to international crises.

But it can be misleading to compare the Liberty to the Maddox. No one in the Administration wanted to strike against Israel, and we did not do so; but for years elements in CINCPAC and the CIA have wanted to strike against Communism in Asia. On August 4 we did. The most important revelations about the Tonkin Gulf incidents are not the mistakes—delayed cables, the inadequate procedures for review. The most important revelation is of another recurring pattern—the readiness of our national security bureaucracy to escalate in Southeast Asia for the attainment of bureaucratic objectives, with or without a provocation.

At one level the objectives may appear to have been relatively finite—the passage of the Tonkin Gulf resolution (which Johnson had decided upon after the first Tonkin incident), the forestalling of international pressures for a Geneva Conference, the revival of Saigon’s interest in an ill-starred war, or the quiet deployment of aircraft for a “forward strategic position” against China. But for some at least the long-range objective seems to have been “a rollback of Communist power” in the area. Although such fantasies may not have been widely shared in Washington, the air strikes and troop deployments of August 5 fitted into a long-continuing build-up of US strike forces around China’s periphery. (Even America’s apparent disengagements, as in 1954 and 1962, have always been balanced by new and strengthened commitments to the region.)42

The Tonkin Gulf resolution led not only to a major war in Asia, but to the credibility gap at home. The young in particular have lost respect for those who accepted, without criticism, a clearcut story which no serious student has since found credible. Senator Fulbright himself has said he regrets his own role in the Tonkin Gulf affair “more than anything I have ever done in my life.”43 It is still in his power to re-open the Tonkin Gulf Hearings, to question Admiral Sharp and other relevant witnesses, and to demand publication of the intercepts on which the strike decision was based. To do so may cause trouble between Congress and the military, but will hardly increase public disaffection. The truth (and the search for it) will more likely allay the worst apprehensions of the anti-war movement. Congress is implicated in the deception of Tonkin; its own credibility is at stake. Many believe our political system is now so militarized, Congressional powers are irrelevant, or subservient, or somehow collusive. Senator Fulbright, will you prove them wrong?

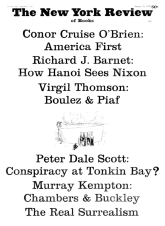

This Issue

January 29, 1970

-

1

US Congress, Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, The Gulf of Tonkin, the 1964 Incidents, 90th Cong.; 2nd Sess. Cited hereafter as Hearing.

↩ -

2

Against McNamara’s professed ignorance of any formal claim before September 1964, Goulden cites Deputy Secretary Cyrus Vance’s statement on August 8, 1964 (“I think that they do claim a 12-mile limit”), and a Navy Intelligence message of May, 1963. According to The New York Times (Aug. 11, 1964, p. 15) the Ticonderoga‘s Task Force Commander Rear Admiral Robert B. Moore “indicated that the destroyer might have been two or three miles inside the 12-mile limit set by Hanoi for international waters.”

↩ -

3

As evidence for his proposition, McNamara cited two cables from Adm. Johnson envisaging withdrawal, while he overlooked the cables from CINCPAC which promptly overruled them. (Hearing, pp. 31-32).

↩ -

4

Only one Maddox crewman claimed to have seen anything—the “outline” of a boat. Two marines from the COMVAN claimed to have seen lights near the ship—but Maddox officers, with their greater sea experience, suggested the “lights” were phosphorescence from a breaking wave (Goulden, p. 151).

↩ -

5

Goulden learned this story from Seaman Park, whose name was somehow omitted from an allegedly complete list of Maddox crewmen supplied by the Pentagon.

↩ -

6

McNamara explained he could report his exact words because “I have a transcript of that telephone conversation” (Hearing, p. 56). Two hours later Fulbright asked for the transcript, since the Defense Department had agreed to supply all relevant communications. McNamara first replied that he would be happy to make it available, but soon qualified this promise by saying he did “not know how much of this will be recorded.” Forgetting what he had said earlier, he now stated that “the source of my statement is my memory of what I myself said and did” (pp. 60-61). This important discrepancy is unfortunately overlooked by Goulden (pp. 152-53). The transcript has apparently never been supplied.

↩ -

7

Hearing, p. 92.

↩ -

8

The orders were directed to two of North Vietnam’s “Swatow”-type motor gunboats (armed with two 37 mm. deck guns but without torpedoes) and to one PT boat “if the PT could be made ready in time.” It is difficult for those with naval experience to believe that lightly armed motor gunboats could be ordered to attack two US destroyers.

↩ -

9

All of the published official reports about the second incident confirm the original report in the Times that the United States suffered no hits, damage, or casualties (NYT, Aug. 5, 1964, p. 1). Thus the report of two downed US aircraft would indeed seem to be, as Goulden concludes, a “total untruth” (p. 153).

↩ -

10

The hypothesis that American intelligence was responsible for the fourth “intercept” itself raises problems, e.g., why would the intercept say that two planes had been shot down when Washington would have known this was not the case?

↩ -

11

If the third and fourth intercepts are valid, how are we to account for the conflicting testimony of the North Vietnamese prisoner-of-war? US naval intelligence officers who interviewed him for more than 100 hours in 1966 reported that he was “co-operative and reliable . Yet he specifically and strongly denies that [on Aug. 4] any attack took place.” [Hearing, p. 75: Goulden, p. 213] McNamara anticipated the Fulbright Committee’s questions about the prisoner with a new piece of evidence.

↩ -

12

The North Vietnamese PT squadron commander should also be interrogated, unless (as has been rumored) he has since been returned to North Vietnam in an exchange of prisoners.

↩ -

13

McNamara, in his carefully worded written statement, said it would be “monstrous” to insinuate that “the Government of the United States induced the incident on August 4.” Misquoting him, Goulden says “McNamara has called it ‘monstrous’ to insinuate that the August 4 incident was a manufactured lie, product of a plot of the White House and the military; I agree.” I do not know if Goulden, in this apparently casual language, intended thus to leave open the question of a plot by intelligence personnel. In any case he does not pursue it.

↩ -

14

I. F. Stone, “McNamara and Tonkin Bay: The Unanswered Questions,” New York Review of Books, March 28, 1968, p. 11.

↩ -

15

Saigon Post, July 23, 1964; I. F. Stone’s Weekly, Sept. 12, 1966, p. 3.

↩ -

16

Aviation Week, June 15, 1964, p. 21; June 22, 1964, p. 15.

↩ -

17

Adm. U. S. G. Sharp and Gen. William C. Westmoreland, Report on the War in Vietnam (As of 30 June 1968), (US Government Printing Office, 1969), p. 85; cf. p. 12. At the time Sharp told a Time reporter that on August 4 “he made about 100 calls to Washington.”

↩ -

18

As it was, the Constellation, delayed by storms, was still some 200 miles out from Yankee Station when her striking planes took off.

↩ -

19

On both occasions Sharp gave his orders while aboard a plane returning from Vietnam; as a result he was unusually difficult to reach from Washington.

↩ -

20

The apparent delay of 90 minutes contrasts sharply with the five or so minutes it took aircraft to arrive during the first incident, before the President’s orders.

↩ -

21

Hearing, p. 31.

↩ -

22

Right after the Tonkin Gulf incidents, someone leaked a study prepared by Willard Matthias for the CIA Board of Estimates, which foresaw a “prolonged stalemate” in Vietnam, and the possibility of “some kind of negotiated settlement based on neutralization” (NYT, Aug. 23, 1964, p. 1; Dommen, Conflict in Laos, p. 298).

↩ -

23

Roger Hilsman, To Move a Nation, Doubleday, 1967, p. 318.

↩ -

24

Hilsman, p. 314. Ironically Nixon has now promoted Cline to Hilsman’s old post as Director of Intelligence and Research in the State Department.

↩ -

25

Tom Wicker, JFK and LBJ: The Influence of Personality Upon Politics (Wm. Morrow, 1968), p. 205.

↩ -

26

Edward Weintal and Charles Bartlett, Facing the Brink (Scribners, 1967), p. 72.

↩ -

27

Goulden, pp. 87-91; cf. Hilsman, p. 534; Weintal and Bartlett, pp. 73-75.

↩ -

28

The less euphemistic phrase “punch-for-punch” seems more appropriate: the Sullivan group contemplated bombing a North Vietnamese factory if the Viet Cong killed a village official, which is hardly “tit-for-tat.” Needless to say, the air strikes against PT boat bases and petroleum installations on August 5 were hardly “tit-for-tat” either.

↩ -

29

American Security Council, Washington Report, June 22, 1964, p. 3.

↩ -

30

London Times Aug. 6, 1969, p. 8; Franz Schurmann, Peter Dale Scott, and Reginald Zelnik, The Politics of Escalation (Fawcett, 1966), pp. 35-43.

↩ -

31

Fred Greene, US Policy and the Security of Asia (McGraw-Hill, 1968), p. 237: “One reason for the American reaction on August 4 was the need to stabilize a deteriorating political situation in Saigon, and in this regard the bombings proved to be of some, though limited value.”

↩ -

32

NYT, Apr. 17, 1964, p. 1; Apr. 19, 1964, p. 82; Richard Nixon, “Needed in Vietnam: The Will to Win,” Reader’s Digest (Aug. 1964), pp. 42-43.

↩ -

33

Kenneth Todd Young, Negotiating with the Chinese Communists: The United States Experience, 1953-1967 (McGraw-Hill, 1968), p. 269.

↩ -

34

House Committee on Appropriations, Foreign Operations Appropriations for 1965, Hearings Before a Subcommittee, 88th Cong., 2nd Sess., p. 310.

↩ -

35

NYT, June 19, 1964, p. 5.

↩ -

36

Charles J. V. Murphy, “Vietnam Hangs on US Determination,” Fortune (May, 1964), pp. 159, 162, 227. In 1961 an article under Murphy’s name attempted to vindicate the CIA for its role in the Bay of Pigs by blaming Eisenhower and Kennedy. The CIA had the gall to seek an official State Department clearance for Murphy’s distorted attack. (See Paul W. Blackstock, The Strategy of Subversion, Quadrangle Books, 1964, p. 250.)

↩ -

37

Bernard Fall, Viet-Nam Witness (Praeger, 1966), p. 203.

↩ -

38

In 1966 it was revealed that CINCPAC’s (Admiral Sharp’s) formal mission was to maintain a “forward strategy on the periphery of the Sino-Soviet bloc in the Western Pacific” (NYT, Mar. 27, 1966, IV, p. 10). As early as June 22, 1964, the Times wrote of America’s new “forward strategic position to face Communist China,” of “an anti-Communist strategy that is far broader than the present war effort within South Vietnam.”

↩ -

39

Aviation Week, June 22, 1964, p. 15.

↩ -

40

Denis Warner, Reporting South-East Asia (Angus and Robertson, 1966), p. 191.

↩ -

41

It has frequently been charged that Khanh seized power on January 30 “after the CIA had decided on him as the new ruler” (Alfred Steinberg, Sam Johnson’s Boy, p. 762). Robert Shaplen, whose book seems based to some extent on CIA sources, denies this, but admits that “some of the high-ranking Americans in town knew what was going on” (The Lost Revolution, p. 232). If so, how was it that “the swift coup put the US Secretary of Defense in the humiliating position of having had no inkling from his intelligence sources of the imminent downfall of an allied government” (Newsweek, Feb. 10, 1964, p. 19)?

↩ -

42

As this goes to press, the Nixon Administration is reported to have suggested that, even if peace were achieved in Vietnam, it might be necessary to continue the Tonkin Gulf resolution in force, to back America’s other “international obligations” in Southeast Asia (San Francisco Chronicle, December 18, 1969, p. 13).

↩ -

43

Hearing, p. 80.

↩