The Officer’s Club in the Air Force Compound, Danang Air Base, is a singular structure. On the outside, a weedless lawn is neatly trimmed, right up to the American suburban sidewalk; beyond, a cement paved street with covered sewers. (The Air Force Compound, Danang Air Base, enjoys what is perhaps the only fully covered sewer system in all of Indo-China.) The Club itself is constructed of the best materials, and kept in excellent repair. The kitchen, fitted with the latest of coolers and ranges, could be a showroom for a restaurant supply house. The bar, the lobby, the rest rooms (piped in Muzak), the TV lounges (Dean Martin crooning, “Everybody loves somebody sometime…,” The F.B.I. without commercials), the vast nightclub floor are like the most lavish Holiday Inn.

While some pertinent questions might be asked as to who makes how much doing what, the visitor is ultimately disarmed. Unlike the Vietnam war, the Officer’s Club in the Air Force Compound, Danang Air Base, is a paying proposition. You seldom see it less than packed. At tables on the night club floor, plump nurses sit about playing cribbage during the raunchy floor shows; legions of spreading staff officers soak up tax-free scotch, scoop extra large portions of chocolate ice cream; and twenty-thousand-dollar-a-year fraternity-boy pilots, drunk on beer, whoop and sling their meals at each other…and then buy seconds, often as not, to sling again.

Yet the hilarity is largely forced, hardly true Gemütlichkeit. (Vacantly obedient young Vietnamese waitresses indulging lingering slaps on the backside, beery passes from miserable colonels.) For all the comforts the Club offers, no one really likes it, simply because it is where it is. So an implicit question hangs about the place: “Is it War, or is it this particular war?” along with the implicit answer, “It’s War. War is hell. We all want to go home.” As with the enlisted men, their favorite song, peeled in unison at the end of drunken evenings, almost wailed, is the hard-rock paean: “We Gotta Get Outa This Place.”

On the evening of October 12, 1968, as a grim young honey-blonde from Buffalo bumped mechanically to fraternity house cheers. I heard one young pilot giggle that he’d “turned his camera off” just after the morning run. He had apparently been flying tactical air support, though it would seem more likely that he’d been on a bombing mission over the North. His F-4 Phantom was equipped with a gun camera shooting cine-film.

“Turned your camera off?” I said.

“Surplus ordnance,” he said. “Mission’s over. On the way home, and I see this slope ville (Vietnamese hamlet). So I switch the camera off. Make my pass. Black pyjamas down there scattering like ants about to get stepped on. Ordnance away.”

The point has been made, and it must be well taken, that the real Vietnamese atrocity is atrocity by high policy, the uninvolved, Eichmann-like dictation of free fire zones for artillery and aerial bombardment (with flechette and Beehive rockets, with cluster bombs), which results in the death of many more innocent civilians than the messy mayhem of Pinkvilles. Many die-hard advocates of a military solution in Vietnam see the victims of the Army’s Pinkville “inquisition” as scape-goats. They may have a significant point. Colonel Corson1 has called the policy of free fire zones genocide, and he was referring only to the forcible uprooting of peasants from their ancestral hamlets.

But even those who insist that Pinkville was not an isolated incident are often and ironically trapped by their own rhetoric into ignoring vast areas of the Pinkville sickness, trapped by a rhetoric that brings them full circle to the implicit rationale that hangs about the Officer’s Club, DaNang Air Base: War is hell. At a recent Pinkville protest, a professor of philosophy at Barnard made the logical jump from “high policy is the real atrocity” to “war—not the Vietnamese war, but war generally—is the real culprit.” In a large moral sense, no doubt there is a substantial argument here, but in many respects it is also a blind position. In a large moral sense, one might also argue that war can be ennobling, that otherwise ordinary people are often brought to heights of willing sacrifice.

In fact, beyond their common squalor, wars do differ, and within wars, participants differ. Vietnam is a particular war which is doing some particular things to its participants. It is insufficient to stop with what it is doing to the Vietnamese.

Along with pilots who turn off their gun cameras and dump surplus ordnance, the Naval Hospital Corpsmen serving with Marine squads in Vietnam are a good place to start. (Marines have no medics. Naval Hospital Corpsmen are assigned the duty.)

In early 1967, there was a series of vicious conventional battles, atypical for Vietnam, in the DMZ sector. Entire battalions of Marines, more frequently than was reported, were literally wiped out, after which their savaged remnants would be sent to Okinawa and Subic Bay in the Philippines for refoddering. During March, Delta Company of the First Battalion, Fourth Marines, was caught in this sort of combat. The day before Easter after weeks of circling forced marches through the scrub, with many of their uniforms in shreds, they were ambushed. Five of the company were killed outright, one of them a Naval Hospital Corpsman going after the wounded.

Advertisement

Before retreat was possible, the company was surrounded. Fatigue was epidemic. At dusk, stray exclamations of fatality, broken now and then by stray small arms fire, would crack down the line: “Hey Tassos,” I heard one young corporal shout. “Why don’t you go get my gear and we’ll just get the hell out of here.” A seventeen-year-old private whispered from his hole over to the Captain, “Sir? What’s the scoop, Sir?” They were certain they would be overrun. And yet they accepted it, it was war. (With an enemy many of them respected: “Fuck with the bull and you get the horns,” said a big Guamanian called Quitico.) Whatever it was, it was better than “down there.”

Finally the Captain spelled it out: “You think it’s bad. It’s not so bad. Up here we’re fighting a real enemy [regular enemy battalions]. I’m trained to kill him, and he’s trained to kill me. Down there [in the south, on more characteristic “search and destroy” missions against “VC villages”] we killed so many people we just got sick of it.” “Down there,” I was told by a Georgian second lieutenant called C——, there had been an incident with a Corpsman.

Naval Corpsmen operating with Marine squads play a traditionally difficult role. To begin with they are shunned. At Parris Island, our drill instructors used to tell us, “Watch out for swabbies, lots of swabbies, especially Corpsmen, they’re queer.” All of which was not without reason. The volunteer Corpsman, suddenly introduced into a Marine squad, must prove himself, which, with fair frequency, he does by getting himself killed going after a wounded Marine on the battlefield.

In the course of unconventional warfare, however, such battlefield opportunities are not so frequent.

“We had some guys down there,” Lieutenant C——told me, “they went into this papa-san’s hootch to play some hearts. The Corpsman, he was there too, but just sort of floating around. They weren’t dealing him in. So the papa-san comes around and he says prease to reave, it’s his hootch, he doesn’t want ’em in there. Well they just tell the old guy to dee-dee, scram, but he keeps coming around telling them prease to reave. Finally the Corpsman says, ‘This guy bothering you?’ and that’s all he says. So they finish their game and they go out and what do you think’s happened? The Corpsman’s gone and he’s slit the old guy’s throat with his K-bar.”

This story eventually gained some currency in the Third Marine Division, but it was never published, and the Corpsman was never court-martialed. His superiors and all of the witnesses were apparently unified in covering for him. Occasionally the story was told with disdain for the stupidity of the Corpsman, occasionally with a certain zeal, occasionally as humor. I never heard it told with any sympathy for the Vietnamese.

The impact of American imperialism on practicing American imperialists can be broken down into many such feedback reactions: the volunteer pilot who bombs hamlets on orders, and the perverse initiative of the pilot who shuts his cameras off and bombs them against orders; troops caught up in spontaneous mayhem; troops who premeditate; troops who commit no atrocities themselves, but participate vicariously through enthusiastic retelling; uninvolved troops who witness and keep their silence; the thousands of drafted troops who leave for Vietnam with certain fundamentally decent instincts intact and return saying, “Used to feel sorry for the peasants. Now I just say, fuck ’em.”

Yet—apart from the general observation that counter-guerrilla warfare is difficult, and some stilted interviews after the fact—how particularly, and how specifically, are we in touch with what is happening to the masses of Americans passing through Vietnam? One attentive anthropologist living intensively with a random combat unit could probably tell us more than 100 reporters chasing Lieutenant Calley.

Close up, the commanders of efficient war machines are more clearly seen to be what they are: trained businessmen. Some of the best young officers of the Israel Defense Forces, for example, can be found, sooner or later, at Columbia Business School. The principal criterion of such technocrats is “cost-effectiveness,” to which the concept “atrocity” is as meaningless as the word “love” in a contractor’s bid. Students, moralists, poets may protest, but little matter. At the highest levels, our apparatchiks of the moment are men who derive their style from the dry Fifties, which dissociated sentiment from intellect, even in poetry. The immediate appearance of lunacy (“body-counts” against the continuation of military stalemate) is insufficient, for immediate appearance, after all, is gut reaction, and gut reaction is sentiment.

Advertisement

You must show them, logically, empirically, that their calculations are insane…and all this in the face of their intimidating brilliance at calculation, against the Economist’s recent consideration that, for example, US strategy is succeeding in Vietnam. Yet when it all works out in fact, business methodology in Vietnam amounts as much to salesmanship as to cost-effectiveness. Beyond computation there is promotion, and with it emotion, and ultimately—at all levels and pervasively—debilitation of morale, disintegration of the moral fabric.

During Operation Chinook, in the Co Bi Than Tanh valley near the Street Without Joy, there emerged an ambitious Colonel called Masterpool, apparently well schooled in business methods. He was later to be used as an adept trouble-shooter, taking direct command of embattled units in the DMZ area.

One cannot describe, in a few words, the debilitation which Chinook wrought. As along the DMZ, there was heavy conventional contact with regular opposing units. Unlike the DMZ, the zones were heavily populated. As an efficient commander, Colonel Masterpool, at that time leading the 3rd Battalion, 4th Marines, had to get his troops to wade into main force communist units and hit hard. For him this became not so much a problem of logistics as one of sales. And so Colonel Masterpool began passing out Avis buttons: “We Try Harder.”

His troops went in, came out decimated, and went in again. A lot of people got killed in the Co Pi Than Tanh valley, mostly Marines and regular NLF soldiers, but not altogether…especially near the end. Near the end, something began to disintegrate. The troops, ranging the valley, never quit, but the Avis buttons began appearing stuck into the gaping wounds of dead Vietnamese, their bodies propped against trees along the trails all the way to the Street Without Joy: “We Try Harder.”

“Yea,” they said, “though we walk through the valley of the shadow of death, we shall fear no evil, for we are the meanest mothers in the valley.”2

In early October of 1968 on the same Street Without Joy, I was traveling south from Quang Tri toward Hué with a young Vietnamese. We were riding a motorcycle and both of us were in civilian clothes. Along the route, signs have been posted: “Friendly troops in area. No firing from vehicles.” We were fired at.

The same evening, returning from Hué, we were stopped by the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division, and by the Quang Tri Revolutionary Development Cadres, a CIA/USAID operation. The senior province chief advisor was furious. (“Press! What Press?”) He was a retired Marine Colonel from Texas, a millionaire reactivated by LBJ for the job. He was fat, he smoked a cigar, and he wore a red golf cap. I was told that he spoke virtually no French and no Vietnamese. He had a platoon of MPs living on his roof. His name was Bibb. “What do you mean a motorcycle,” he shouted. “Good journalists come in on helicopters! The New York Times comes in on a helicopter!” What apparently had angered them was that the Vietnamese had gotten away. Their avid proprietary concern over a random citizen of South Vietnam was striking.

I was eventually put under house arrest for the night, and from Bibb’s MPs learned his background, and the reasons for their anger: First, desertions and attempted defections have been rising among GIs in the field. Several days earlier, in utility fatigues, I had asked an MP at Dongha what had happened to the sign that once pointed to Hanoi, and he had said, dead seriously, “What do you want to go to Hanoi for?” Now Bibb’s MPs said, “You see we got a lot of GIs like to put on white shirts and take rides.”

Second, there have been increased shooting incidents between GIs and Vietnamese along the road. (In the wake of Pinkville, Newsday reported the arrest of an American GI, the son of a policeman, for shooting two Vietnamese off the top of a bus. One wonders why the military is only now discovering the scope of such crimes.) This shooting apparently goes beyond the Americans’ predilection for taking pot shots from their trucks and jeeps. Bibb’s MPs claimed ARVN troops had been getting so “confused” that they shot at Americans more frequently than they did at the “enemy.”

A year and a half earlier, I had been with the Combined Action Marines of Cam Lo. (Combined Action Platoons [CAP] are the Marines’ relatively successful, but poorly supported, attempts at close cooperation with Vietnamese in hamlets.) I saw them shoot, on early morning patrol, a young, unarmed Vietnamese in black pyjamas. (“There’s a curfew here…”) The patrol trussed his body to a bamboo pole, and carried him into the ville like the carcass of a deer. They set him down in front of the Cam Lo schoolhouse, and let him rest there. Flies began to swarm in the great gaping hole in his temple. Late in the afternoon, one of the young CAP Marines broke out his Polaroid Swinger, and snapped a picture of the body. Then he took it to show a young girl he had a crush on, a seamstress. “Don’t show her that shit, man,” said his buddy. “What do you mean?” he said. “She likes it. They like it. He’s VC. They hate the VC.” The girl stared, expressionless.

These are perhaps minor incidents by the standards of current news. They may have little significance when compared with the larger Vietnam atrocity, the Eichmann-like atrocity of mass murder by detached policy. They are incidents which matter only when you realize that they are as pervasive as they are “minor,” that they have became the common behavior of hundreds of thousands of young men who will be coming back to this country, conditioned.

The conditioning, to be sure, is not of a predictable sort, least of all among a most significant portion of these young men—blacks and Latins.

Some of them would seem to have become brutalized, psychologically disintegrated tools. In April, 1967, with an infantry company of the First Battalion, Fifth Marines, in the sand dunes just north of the Cua Viet river, I heard a young black describe how the ARVNs had behaved in a nearby ville, demanding chickens and their pick of the young girls. “They handles ’em right.” And he bragged to us how once he’d “caught an old zip,” buried him up to his neck in C-4 (plastique), and “chucked in a grenade.”

More often, what happens is nothing like this. Usually I have seen them begin their tours as earnest young men, models of Jackie Robinson, cheeky but not too cheeky, batting for Uncle Sam. (I remember one exceptional athlete pitching grenades over sandbags at advancing guerrillas while his lieutenant, further back, gave him directions as if he were an artillery piece: “Over nine, down two…”) But then something happens, and those it happens to are not necessarily frustrated and easily susceptible young street toughs; they are those once earnest model young men, the Jackie Robinsons, and what happens to them is tortuous, uncomfortable, resisted from their depths. After the current fashion, we would say they become “radicalized,” but I think it is deeper than that.

I remember particularly a young sergeant from Pritchard, near Mobile. His name was Leon Jordan. I met him at Dongha. He had been wounded in combat, and he was on his way back from the White Elephant field hospital in Danang. At Dongha he was waiting for a jeep to his unit at Camp Carroll, a forward base now abandoned. To Leon Jordan’s mind, it was a bum trip all the way. There was even an order out on it: vehicles must travel in convoy. You just didn’t take a single jeep up a road like the one to Camp Carroll. “Lots of peoples got blowed away, in this war,” said Leon Jordan. “Lots of peoples gonna get blowed away.”

But he’d gone through too much time killing time already, first in the hospital, and now during the trip back: hours spent waiting for transports that never showed up or when they did were too full for one more trooper; hours spent lounging and sprawling in vast open hangars full of lounging, sprawling, sometimes reading, often griping, usually sleeping Marines who would pick at their sores and skate through Stag magazines and Audrey and Melvin comic books. After a time like that, he said, a man just was not fit to ask questions about the last twenty miles of two hundred miles of waiting in line. The jeep came, and we left. And nothing happened. “Nothing ever does.”

Leon Jordan was a tank commander. It’s not the sort of job a man gets by daydreaming. But in the hospital Jordan had time to think. One day he took a pencil and wrote down what he was thinking,

Life is filled with Happiness, tragedy, successes and failure. But before you part from this World leave something you may be remembered by. For tomorrow never comes and a lot of laters on lead to never.

To me, Life is just a Thought, and after you are gone there are only memories. A great man once said that War is Hell. But to me today and many times before, War is our only means of Success.

The saddest words ever spoken or written by man is I could have been if I’d applied myself. Because through God, Fear and War, nothing is impossible.

He kept his scrap of paper, but he looked at it only briefly as he sat on his rack, settling back in his squad bay tent at Camp Carroll. Outside the rolled up sides of the tent, two white Marines lay spreadeagle on a sandbag bunker, baking like lizards in the sun.

“I seen a brave ARVN once,” said one of them.

For a long time the other Marine said nothing. Flies whined. Then he answered. “You don’t say,” he said.

“Yeah,” said the first Marine. “Was with my buddy. My buddy had this hat. And so the ARVN says where did he get the hat, and my buddy says off the ARVN’s dead brother. You shoulda seen the guy. Thought he was ready to take that hat right off my buddy’s head. My buddy decked him. Only time I ever saw a gook try and take something off a Marine.” Inside the tent, Leon Jordan sat without speaking. A minute passed and he leaned forward and pulled a threadbare utility jacket from his seabag. Almost ritually, he began tearing it into rags. “I was trying to convince myself,” he said. “Was trying to see a reason.”

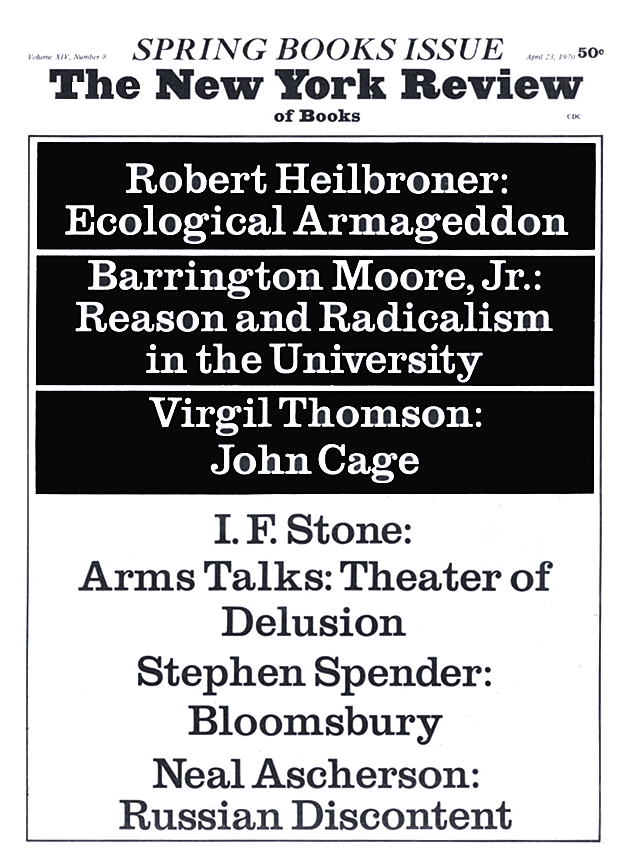

This Issue

April 23, 1970

-

1

Colonel William R. Corson, who published his book The Betrayal in 1968 after twenty-five years in the Marine Corps. He initiated some of the few “successful” counter-insurgency programs in Vietnam, all them in I corps, where I also spent most of my time. ↩

-

2

Chinook was not immediately and never closely reported, though command circles apparently appreciated the significance it would have. As it was quietly launched, a simultaneous “secret” amphibious operation was launched with a “select” group of journalists invited along. Journalists being what they are, others did their unseemly best to be included. The Marines and journalists waded ashore and were greeted by a few fishermen. Meanwhile, Chinook, producing some of the stiffest battles of the war, was getting under way, unattended and far to the south. ↩