In most of the fourteen essays collected in this book Mr. Richard Gilman comes on as the compleat “with it” critic, pushing to the limit his (perhaps) belated conversion to extreme trendiness. A literary journalist and theater reviewer in background, and lately a professor of drama at Yale, Mr. Gilman has shown through the years an almost immodest taste for conversions; and at present he is evidently straining at the leash to launch himself into the role of a leading exponent of the New—of the New at all costs at that—and as a Now prophet of the arts. Thus craving as he does optimal participation in the cult of Now, inevitably for him not ripeness but timeliness is all.

That there is no significant difference between being time-obsessed and being time-bound is one of the many disagreeable facts that Mr. Gilman, so prone to confuse novelty with originality, prefers not to acknowledge. As a critic he is not merely attentive to the Zeitgeist, he is positively enslaved by it, to the point of being unaware that he has the option of opposing its more erratic or jejune expressions. True, he questions John Updike’s reputation as a novelist and attacks MacBird! and Rechy’s City of Night. But these are small game indeed, and Rechy’s trashy novel, a typical Grove Press concoction, is hardly worth serious attention. Only in the essay on the Living Theatre, in which its ostentatious claims to revolutionary probity and efficacy are denied outright, does Mr. Gilman wake up from his dream of an apocalypse of artistic innovation. For the rest, he pursues the fata morgana of avant-gardism and engages in a good deal of aesthetic theorizing, at once schematic and fancy, about iconoclastic models of new fiction and drama.

Still, it will not do to dismiss Mr. Gilman as just another swinger. He moralizes too much to fit that simple category, even if his moralizing takes the form of an all-too-solemn and over-strenuous insistence on new-fangled aesthetic imperatives, mostly of his own contriving. No, his is a case, in my view, of severe moral insecurity. Hence the terrible fear of being left behind, of missing the boat. And the result is a collapse into trendiness.

No wonder Mr. Gilman is so entranced by Susan Sontag, of whom he says that there is no critic “more interesting or more relevant” today. Yet if we read his remarks on Miss Sontag carefully enough we soon realize that, though voicing his disagreements with truly extraordinary discretion, specifically he does not really agree with her about anything of consequence. It is plain that what he chiefly admires in Miss Sontag is the hypertrophic image she seems to have acquired—that of the siren of eroticized aestheticism and of the so-called “new sensibility.” The total up-to-dateness of her public posture appeals to him; what matters is not her detailed argument but the trend she appears to embody. But I for one am not at all certain that Miss Sontag would care to identify herself unreservedly with the “image” to which Mr. Gilman pays homage so extravagantly. After the first careless raptures, who knows what Miss Sontag will turn to next?

The same pattern of obeisance to current trends is repeated in the essay on McLuhan. It seems that the latter, though not quite the great thinker the media have made him out to be, is nevertheless very important and must be defended against his detractors. The essay swings between adulation and demurrers all too tentative. In consequence there is nothing substantial in it to lay hold of, no definitive assessment but just one more trendy piece, full of profuse and idle talk.

But what is Mr. Gilman’s basic idea and recurrent theme? It is that art is a kind of “counterhistory” and that works of art stand outside history “as a species of alternative” to it. He asserts that fiction, for instance, “is better off if stripped of its burden of ‘information,’ of portraiture and sense of actuality; denuded in this way, it can begin to be…more purely verbal artifact and imaginative increment.” Thus divorcing fiction from lived experience and any function except the aesthetic one, he even goes so far as to contend that it must employ language “for no end beyond itself.” And what he means by “the confusion of realms” is simply the confusion of art with life. His main concern is to make art impermeable to life, a self-sufficient imperium where the imagination restores to us the very things which history failed to provide.

Now admittedly confounding art and life is among the major fallacies of some kinds of criticism. A parallel, fallacy, however, and an equally damaging one, is the failure to see their close and necessary relationship. Mr. Gilman’s critical position is obviously the epitome of the latter fallacy; and his advocacy of an autotelic language for fiction is surely preposterous, as it flies in the face of the entire history of that genre. Nor does Mr. Gilman cite a single fictional work of substance, universally recognized as such, which even begins to correspond to his basic idea, the essence of which is sheer abstraction. Clearly, to dispossess narrative composition of the “sense of actuality” is to doom it to sterility. If you deprive novels of story, character, suspense, and, above all, of the pressure and control of the actual, you thereby deprive readers of the prime incentive that keeps them going; and the substitution of “more purely verbal artifact” is no better than a prescription for boredom. Actually, the resource of the “verbal artifact” has been tried time and again in recent decades and it has always failed. To mention but two outstanding examples: Consider how little interest there is today in Gertrude Stein’s linguistic exercises or in Virginia Woolf’s for that matter (insofar as she went in for that sort of thing at all).

Advertisement

Moreover, Mr. Gilman naively uses the words “life” and “history” as if they were synonymous. But they are by no means synonymous. The modern mind has endowed historical life with a structure and significance which it cannot perceive in fortuitous, amorphous, quotidian life—on the political and cultural plane at any rate. What Mr. Gilman has done is to carry to an absurd extreme all the discredited, superannuated notions of the old hyperaesthetic and art-cultist movements and to present them to us as a new revelation that will inaugurate an artistic revolution. This delusion he tries to sustain by importunate theorizing. This much can be said about theories of literature, however; they are virtually useless unless empirically derived from the actual history of literature, from its concrete practice in the ever-continuing process of continuity and change. Otherwise they remain speculative abstractions, devoid of apodictic value. Mr. Gilman’s theorizing is futile because he is in fact legislating a program for literature rather than elucidating and analyzing its development. And legislation is not criticism.

Nor does Mr. Gilman have the virtue of consistency; his trendiness precludes it. Given his penchant for the purest aestheticism, it is curious that he cannot leave Norman Mailer alone. The longest and most acclamatory essay in the book (and the most turgidly written besides) is devoted to the study of his career. But Mailer is a writer thoroughly engagé, involved with life at its most immediate and contingent. In other words, he is the diametrical opposite of Mr. Gilman’s ideal artist, who is scornful of both life and history.

The contradiction is too patent, and he strives to overcome it by devising a nimble formula. It comes to this: Mailer’s novels represent no real achievement, for they are much too conventional and traditional in technique and style. The Armies of the Night, however, signifies a break-through to supreme artistry. Here he has finally and masterfully come into his own. So Mr. Gilman does not so much analyze Armies of the Night as canonize it as a work of art, not as a work of political reportage. For him the confrontation at the Pentagon is not the heart of the book; instead he concentrates on the author’s ego-games and inordinate self-dramatization, which he treats with the utmost seriousness. In this manner Mailer is transmogrified into an aesthete of the latest vintage, while Mr. Gilman remains “with-it.”

Mr. Gilman satisfies his appetite for trendiness even more ingenuously in an essay entitled “White Standards and Black Writing,” in which he deserts his “confusion of realms” theme, plunging into political moralizing without so much as turning a hair. The essay is an extended comment (or non-comment) on Malcolm X’s autobiography and Eldridge Cleaver’s Soul on Ice. One might think that Mr. Gilman would take care to avoid such writing, as he is an amateur, if ever there was one, in the social and political sphere. But no, Mr. Gilman boldly takes on the race issue by coming forward with the declaration that white critics, to appease their consciences, must refuse to undertake any assessment of writing by black authors. His reasons for adopting that quasi-ascetic stance seem to me deeply symptomatic of the obsequiousness that not a few white liberals have fallen into when confronting the revolt of the blacks. This revolt, to be sure, is entirely justified on political grounds. What is not justified, however, is the white critic’s renunciation of his own function in an ecstasy of self-abasement, rationalized by Mr. Gilman in the following statements:

About Malcolm X’s Autobiography:

…It was not written for us, it was written for blacks…. The black suffering is not of the same kind as ours….

About Cleaver:

Advertisement

His writing remains in some profound sense not subject to correction or emendation or, most centrally, approval or rejection by those of us who are not black.

Again:

…In the present phase of interracial existence in America moral and intellectual “truths” have not the same reality for blacks and whites, and that even to write is, for many blacks, a particular fact within the fact of their Negritude, not the independent universal “luxury” which we at least partly and ideally conceive it to be.

And further on:

We can no longer talk to black people, or they to us. The traditional humanist ways, the old Mediterranean values…are dead as useful frames of reference or pertinent guides to procedure….

The multiple confusions with which Mr. Gilman’s foray into our “interracial existence” abounds are simply appalling. In the first place, in the face of his self-confessed inadequacy, why undertake to discuss Malcolm X and Eldridge Cleaver at all? Yet not only does he discuss them at length but even generalizes from his own case to include all white critics. “Black suffering is not the same as ours.” But what about the suffering of the prisoners in Hitler’s and Stalin’s concentration camps? Is that the same as ours? And what about the Russian experience as rendered by novelists from Dostoevsky to Solzhenitsyn? Are these novels forbidden territory to Western critics, who have had no part in that experience?

I venture to say that the Russian experience as a whole is more alien to white American critics than the “black experience.” Being inhabitants of the same country, white writers know more about blacks, though from the standpoint of relative outsiders, than they can ever know about the kind of people that Dostoevsky or Solzhenitsyn bring to life in their pages. Mr. Gilman is in effect denying the solidarity of the human species, its unitary character and essential oneness.

Furthermore, the books by Malcolm X and Cleaver are not primarily works of art nor meant to be. Nor were they meant to be read only by blacks. On the contrary, their books have been read by millions of whites and were actually written, in good part at least, with that purpose in mind. Lacking a language of their own, black authors must necessarily suffer the constraint of having a white reader peering over their shoulders even as they write. As for Mr. Gilman’s implied sneering dismissal of “the traditional humanist ways” and “the old Mediterranean values,” what do the black militants depend on when appealing to our feelings of guilt and sense of justice if not to these very same humanist ways and Mediterranean values? If it were not for these ways and values, why should whites sympathize with the blacks and support their cause? Without such support their cause is lost indeed.

The truth is that Mr. Gilman’s phrases go beyond any perceivable content when dealing with the present phase of our “interracial existence.” In speaking about race as if it were an ultimate, irreducible, almost extrahuman fact, he is not really addressing himself to the problem at all but giving in to the present literary trend of absolutist and outrageous asseveration. His reverential hush before the fact of blackness does not in the least impress me. It reminds me, rather, of those “mental masses,” of whom Saul Bellow speaks in his last novel, the urban liberal masses that have somehow “formed an idea of the corrupting disease of being white and of the healing power of black.” As I see it, it is not a stricken conscience but incorrigible trendiness that accounts for Mr. Gilman’s melodramatic abstention from considering black writing from a critical standpoint.

But his compunction in the face of the black experience fades instantly upon entering the privileged sphere of “aesthetic experience” and “aesthetic intelligence.” Here he enacts his programmatic role con brio, priding himself on his ostensibly advanced ideas while in effect dismissing all past and present criticism as “academic” or “traditional.” Except for Miss Sontag, hardly any twentieth-century critic is cited and taken into account as having contributed to our aesthetic enlightenment. Reading his book, one might conclude that Eliot, Pound, Wilson, Empson, Richards, Leavis, Tate, Ransom, Blackmur, Warren, and Trilling (not to mention any European critics) are just so many humdrum academics who never said anything of note pertinent to the theme of art versus life.

Having thus fabricated an impoverished world of critical discourse, Mr. Gilman is naturally free to cut a great figure as the lone defender of the imaginative transaction and the exigent instructor of its mysteries. But this is fantastication pure and simple, or, to phrase it more plainly, the crudest of put-ons. The “with it” critics who have emerged in the 1960s are apt to ignore the rich, innovative critical tradition of the century in an effort to appropriate for themselves exclusive rights to the ethos of avant-gardism. In this respect Mr. Gilman is exemplary, but only in the sense that he deserves to be made an example of.

T. S. Eliot is undoubtedly the finest critical mind of the English-speaking world in this century. Yet Mr. Gilman makes not even the slightest effort to deal with his ideas; he is not even mentioned. I wager that he would be wholly disconcerted if forced to contend with any one of Eliot’s main critical dicta. Take, for instance, the following statement: “The greatness of literature cannot be determined solely by literary standards; though we must remember that whether it is literature or not can be determined only by literary standards.” Or take this one, from “A Dialogue on Dramatic Poetry”:

You can never draw the line between aesthetic criticism and moral and social criticism; you cannot draw a line between criticism and metaphysics; you start with literary criticism, and however rigorous an aesthete you may be, you are over the frontier into something else sooner or later. The best you can do is to accept these conditions and know what you are doing when you do it. And, on the other hand, you must know how and when to retrace your steps. You must be very nimble. I may begin by moral criticism of Shakespeare and pass over into aesthetic criticism or vice versa.

Suffice it to say that Mr. Gilman’s sanctified aestheticism is contradicted at every step by Eliot’s clear and precise observations. Mr. Gilman’s most egregious error lies in conceiving of the aesthetic element in literature as some kind of abstract and permanent essence detachable from the contingencies of life and the inescapable historical circumstances. But in fact there is no such essence. It is always a part of something else, and if it appears at all it is always among other things, never alone; secreted by any sort of material lending itself to skillful shaping, it cannot be isolated or discovered in a pure state. Because it is a quality the beautiful difficulty of which is inseparable from its elusiveness, any attempt to converge upon it in a strictly purist manner is to hypostatize it, the result not infrequently being a kind of aesthetic fetishism that turns the actual inside out. And that is why we are prone to use the term “aesthetic” without knowing exactly what we mean by it. This not quite knowing, this uncertainty, is, to my mind, far more imaginative than Mr. Gilman’s tight grasp of an honorific abstraction.

It has been far from my intention to present Mr. Gilman as a writer endowed with a genuine and acute aesthetic sensibility. For one thing, the inveterate journalist shows through the aesthetic mask all too often; for another, he moralizes overmuch, though without evincing any serious interest in durable moral issues. What it comes to is that he is a mere raisonneur of newness per se, anxious not to miss out on the very latest permutation of the Zeitgeist, however casual or meretricious, whose turgid, laborious prose and graceless conceptual mode attest to the decline of the discipline of criticism in our time.

How could it be otherwise, considering that in the twentieth century criticism has been principally concerned with the vindication of the classic avant-garde, with formulating and elaborating its motives and aims? But this critical function is exhausted at present, and the rush to be “with it” provides only a vulgar alternative. Not that the impulse to authentic artistry has wholly atrophied in this period; it still persists in a marginal way even if increasingly dissociated from the avant-garde principle of the recent past. The fact is that what now passes for avant-gardism, as the larger public understands it, is little more than a rummage sale of its historic antecedents; and the self-styled vanguard of today plays up to the refinements and creative triumphs of the past as a means of putting over its low-grade imitations and the random shots of confused though excessively ambitious epigones. No wonder this vanguard is so affluent, flattered by the media and accepted without resistance or admonishment by the bourgeois of Flaubertian lore, now declassed in every respect save the fixed and inflexible resolve to preserve the cash nexus.

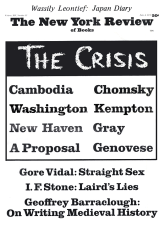

This Issue

June 4, 1970