Newark, N.J.

On June 16, the voters of Newark decided whether to have the first Negro mayor to be elected by the general populace of a major eastern city. The outcome was not known in time for publication here. In any case, the ultimate result is inevitable: the captains of the white garrison already suspect that there are more Negro voters functioning in Newark than white ones; if that is not true now, it will be soon enough; population projections indicate that, within five years, Newark will be close to 70 percent nonwhite.

This moment, whether of fulfillment of that trend or its mere postponement, carried more than usual of the gaudy ironies which have always attracted metropolitan journalists to the politics of Northern New Jersey as to an entertainment of circus animals: Mayor Hugh Addonizio sits before the federal jury trying him for extortion by day and campaigns only at night, forced, after years of dependence on the Negro vote, to arise now as champion of the white resistance. Kenneth Gibson, his opponent, has the support, in all three instances useful, of both Newark newspapers, of the ex-policeman who had been the candidate of the Irish only recently displaced by the Italians, and of the poet LeRoi Jones (“Poems that wrestle cops into alleys / and take their weapons leaving them dead / with tongues pulled out and sent back to Ireland.”).* Still, something has happened in Newark more consequential than the accustomed comedy of its elections.

The Negro ticket—“The Community’s Choice”—consists of Kenneth Gibson and four candidates for councilman-at-large, one a Puerto Rican. Mayor Addonizio—“The Peace and Progress Ticket”—runs with three Italo-Americans and a Negro, Calvin B. West, who took the normal course of Newark politics and might have been mayor if the transition had been an orderly succession from a Jewish to an Irish to an Italian and, some convenient day hence, to a Negro mayor—each rather like the rest—as was to be expected in Newark. As it is, Calvin West has ended under indictment with Addonizio but otherwise alone; he ran far behind the Puerto Rican (a man who was nominated, along with Gibson, by the “Black Convention”) in his own black Central Ward in the first election.

None of these persons is as familiar as LeRoi Jones, and only Addonizio has a chance to be as notorious. The Mayor has ended up campaigning only against LeRoi Jones; the most conspicuous piece of anti-Gibson literature is a reprint from the Elizabeth Journal of February 3, 1968, at the top of which the Mayor’s friends have emblazoned, “LeRoi Jones—Gibson’s Chief Aid—says ‘Kill Whites Right Now.’ “

This species of citation gets itself talked of as racist—it does at the very least attempt to give horrid form to fears otherwise formless. The Mayor, before he recognized that he had no other way to go, was sufficiently embarrassed to disown it and to promise instead a brochure worthy of his dignity detailing his prodigies for progress. Still LeRoi Jones did say these things; and the poet, more than most, has a right to be judged by the poem, which ought, after all, to aim to be more enduring than a political promise.

What is curious is that these sentiments should have been arraigned only now from a garrison under the heaviest siege. An unsophisticated tolerance is one of the charms of Northern New Jersey; it is not often that one of its high-school graduates gets himself famous and still comes home. That act of return was felt to be as much a compliment to Newark as it was a necessity to LeRoi Jones, and he became an established, even a respected, figure.

“When Jones first came back,” Donald Malafronte, the Mayor’s assistant says, “you would have thought from the papers that his full name was ‘Militant Playwright LeRoi Jones.’ Then they began calling him ‘Barringer High School Graduate and Guggenheim Fellow LeRoi Jones.’ He is now an educator and a city planner.”

Those ethnic insults which constituted so much of the donnée of his years wandering away from home may turn out indeed less useful to his opponents than our standards for discourse ought to conceive them as being. The slur upon country of origin is a custom in Northern New Jersey; it shows up, as repetitive as, if less imaginative than, Jones’s own slurs, in those Mafia transcripts which seem to constitute, along with his, the entire body of work published by residents of Essex County during the past year. And Jones shares—indeed heightens—the local habit of specificity in this style: “dagger poems in the slimy bellies of the owner-Jews…knockoff poems for dopeselling wops.” This is, or was anyway, a disgusting side to the man. But it was not sufficiently alien to the environment to make it easy for the Addonizio forces to gather together three Newark voters of different ancestry and to tell them what Jones said about persons of the national origin of one member of the audience without running the risk that the other two would find it fair comment.

Advertisement

“I was talking to an Italian girl in the North Ward,” Donald Malafronte says, “and I told her that Jones had said Hitler didn’t kill enough Jews. You know, she just nodded her head.”

No sense of Newark seems possible then without the pilgrimage to Spirit House where LeRoi Jones sits as Imamu Ameer Baraka, director of the Jehad Press, manager, to its satisfaction, of an Office of Economic Opportunity grant. There is the suggestively royal touch of gold-colored thread in his dashiki; downstairs the visitor is most politely reminded not to smoke; upstairs his secretary comes in, her hands clasped before her, soft and tiny with a soft and tiny voice, bowing and apologizing: “Imamu, there is not enough honey for your tea.” He has never been more African and not for a long while more affable. There is no bardic effort to veil the shrewdness of the eyes, and only the faintest suggestion of the mellowest line from the time of his wanderings,

The white man

at best

is

corny.

Newark, he reminds his visitor, is a very conservative, a southern city. There is no irony at such a thought in such surroundings. Exotic they are, of course, but they are also ascetic and ceremonious enough to have the approval of that father of LeRoi Jones’s who worked so long in the Newark post office.

It is an exaggeration—made pardonable by his circumstance—for Mayor Addonizio to describe LeRoi Jones as Kenneth Gibson’s chief aid; even so, Jones contributed an immeasurable part to what is unique in the process by which Newark’s particular Negro community has moved toward the control of its politics. The first Black Power conference was scheduled for Newark before the 1967 riots and was carried through after them, paid for by a consortium of the Chamber of Commerce, the telephone company, and the Episcopal Diocese of New Jersey. There has never been any plausible explanation for this gesture of hospitality by those few in Newark who were comfortable for the slightly less few who were enraged, except that, in a city where no resident has any sense of power, the threat of Black Power, not too tangible anywhere else, must seem even more abstract.

The results of the first Black Power conference were as drab as its plumage was radiant. The next year, reformed as the Black Community and Defense Organization, its conference drew even less attention, attracting as it did fewer of the strange birds of the revolution from the great world outside. Then in the fall of 1969, the conference was reconstituted as the Black and Puerto Rican Convention and nominated Kenneth Gibson and ten candidates for City Council. The habit of excluding whites had survived from the first Black Power conference; those Negro politicians who had made their way in normal fashion and come to depend upon white politicians had therefore to choose between keeping those ties or attending the Black and Puerto Rican Convention. Their defection cost little that was substantial; Newark had no sitting black officeholders functioning except as conduits for City Hall patronage. The black “Community’s Choice” could begin free of complicity with the past; what is more, since Gibson is hardly a conspicuous personality, it seemed politic to group the Mayor-designate and his fellow candidates together as a team.

“Some of the most conservative Negroes in the city suddenly understood ‘We have a clear way out of this,’ ” LeRoi Jones says. “What after all can the conscious do until they can reach the unconscious? Without that there can be no movement; it becomes literary, academic, an art form.”

Kenneth Gibson got 41 percent of the votes in the first May election, more than twice as many as the Mayor. It is hard to believe that he got more than 5 percent of the white vote. Still he was almost strong enough with his own base to win the election alone; and the sudden respect his opponents feel for the black voter is for the intrusion of a disciplined bloc into a politics where the candidate of custom had traveled alone. Newark had hardly ever seen a united ticket in municipal government before, except, of course, last spring when a substantial majority of the 1965 City Council was indicted with the Mayor for extortion.

The black vote was so taut, in fact, that its Puerto Rican City Council candidate rode over Calvin West in the two largest Negro wards. That example of unity could not be resisted; Mayor Addonizio could only draw together for his last stand the surviving white councilmanic candidates—at least one a long-standing enemy—into what he called “The Peace and Progress Ticket.”

Advertisement

“We have given them something new,” LeRoi Jones smiles. “We ran collectively. Now we got them running collectively. Have you seen their new posters with the colors and all the pictures the same size? That is an example of how rock-and-roll was born.”

There is a staff of the McCarthy-Kennedy veterans downtown on Broad Street; yet never have these superb young commanders seemed less in touch with the real event, which moves and draws its strength from sources unknown, talents invisible.

“We must win in the end,” said LeRoi Jones, “because the great majority of us are not going anywhere else. They made the mistake of all poor whites; they never understood that the owners were still on the set, and their morals were as bad as the owners’. We know that the owners will be on the set even after we win; but the morality of the managers will at least be higher than the morality of the owners.”

As his visitor left LeRoi Jones was pleasantly but authoritatively wondering over the telephone to the proprietor of an off-Broadway theater why only Oh! Calcutta! and No Place to Be Somebody had agreed to give benefit performances for the Gibson campaign. Even when he was most outrageous, there had been this shrewdness: hadn’t he, while proclaiming his hatred of everything white, also judged that most Negro writing could be thought of as serious only “if one has not read Herman Melville or James Joyce”? He should then not surprise us in this case; he always, on important occasions, if not about important matters, had a sense for the ground upon which he argued.

It is odd, in view of such complexities of source, how conventional a candidate Kenneth Gibson seems to be. Everyone who runs for office in Newark seems to have worked for the city in some prior and recent manifestation. Two of Addonizio’s running-mates for councilman are former policemen; two of Gibson’s work in poverty programs whose funds were beseeched by the Mayor from the federal government. But Gibson is a city engineer with no history of agitation and with a style almost ponderous in its communication of stability.

“By law, I’m an expert in my profession,” he tells audiences, white and black. “In me you will get a recognized expert professional for the same price as a corrupt amateur…. You must look at Newark as a corporation, as a business. If you have a poor corporation, you have a poor product. We need the best qualified people for every top position. We cannot afford the traditional political hacks.”

The revolutionary moment is devoid of epiphany; what approaches now is the black mayor LeRoi Jones’s father might have chosen. Still, as Gibson travels around the white districts, there is the fear, held back at first, then pouring out near the end of the question period. He talks to a mixed group of pensioners in a housing project. They sit in an assembly room with no portraits as decoration except those of Franklin D. Roosevelt and John F. Kennedy. They seem glad to see him, but pensioners are grateful for any visit. It is late in his welcome before a woman calls out, “Will you come out here and protect us?” and there are interruptions with the tales of muggings. And Gibson comes with weary dignity to The Subject: “Cleveland has a black Mayor, and Cleveland still exists. They will tell you there is something strange about black people. You see what I am—same schools, same colleges, same kinds of desires. My wife would like to be able to walk the streets safely.”

He moves on to a luxury apartment in the North Ward; the liberals there are unexpectedly more savage, being, one supposes, better informed. Their tones, when kindly, are snobbish, and they are not often kind: “Where can you get funds for building with the money market what it is?”; “What are we going to do for people who don’t commit crimes?”; “How about the kids who aren’t taking dope?”; “How do you meet the LeRoi Jones issue?” He assures them good-humoredly at the end that there is no cause for them to worry about “me carrying spears and chasing people down the streets.” The ponderosity, the weariness are all explained. You almost feel the ordeal as your own. There is no such animal as a conventional black candidate.

“Regardless of confrontations, just walk away,” he tells an audience of Negroes in the South Ward. “You should be able to take a little name-calling because you’re doing it for the good of the city.”

Fear is there then; and the whites of Newark offer a meager prospect to any candidate seeking any hopes of theirs to speak to. The question is whether even their fears can arouse them. Hugh Addonizio has nothing else to depend on; he is indicted and outnumbered, his wife is ill, he needs a court’s permission to travel so far as his son’s college graduation. He cannot have been a very cheerful man even when things were easier, being bald, neckless, and cast over with a melancholy which must have begun long before his troubles became public and which can be explained by the unfairness of life to everyone in Newark: The Mayor was barely elected before some mafiosi were complaining that he had taken their campaign contributions and failed to support them, such apparently being the shifts required for a politician in a city where more respectable businessmen no longer care enough about public affairs even to finance a politician.

Now the Mayor can only run as the white candidate. It is a process not easy for him to learn; he is by nature progressive and has reason to appreciate his Negro population because, without its depressed condition, Newark would have been deprived even of those slums which have been its only attraction to federal funders. And then the materials for raising the alarm are scanty; his researchers had to go to the John Birch Society’s American Opinion to find out the worst about Mayor Carl Stokes of Cleveland. It would be late that night before Addonizio could goad himself to remind his final audience that, while Gibson spoke so soothingly of Cleveland, its crime rate had risen 45 percent in a year.

He was unable yet to mask embarrassment while Larry Gately introduced him to the East Ward: “He is running against one of the violent Black racists. His advertisement is ‘Rape whitey’s women.’ ” He traveled with what encouragement that message could give him to the North Ward, bastion of Anthony Imperiale, the karate teacher who had been Newark’s loudest alarm bell against the blacks. Imperiale was absent, his dignity not permitting him to welcome someone who had called him a “neo-Nazi” in the previous election. But his club was open to the Mayor and his three major ward campaign directors—all school-teachers by the way—were in attendance. The crowd was small and rather too cheerful to reward for the moment any hopes that the North Ward would commence to boil and shake. One felt a certain acceptance of that against which it seems no longer useful to struggle. There was a propriety to the proceedings impossible to associate with an army desperately at bay; one lusty youth did cry, “Beat that Nigger”; he was cut off by reproaches and four of his elders went over to chase him away.

Their warmest applause was for Calvin West, the last elected Negro still afoot with them.

“I want you to get mad,” Calvin West ended. “I want you to get mad. It is your city.”

To think oneself a successful Negro, to fall under indictment, to have no hope of even the shadow of rescue unless the North Ward gets mad, to be alarmed to find the ugliest passions apparently sleeping—such is the history of careers in Newark. They have been bound, all its citizens, by common failures and common regrets, not often enough able to afford the sense of shame. No wonder LeRoi Jones, who grew up with them, has never seemed less to suggest that it is a pleasant thing to be one of the executioners.

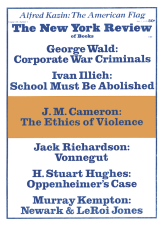

This Issue

July 2, 1970

-

*

This and other quotations from his poetry are from LeRoi Jones’s Black Magic (Bobbs-Merrill, 226 pp., $5.95).

↩