It seemed to me that I was floating far above the earth, toward a transfigured old man whose appearance filled me with something higher than mere respect. Whenever I opened my eyes toward him, I was penetrated by an irresistible feeling of reverence and trust, and I was about to prostrate myself before him, when a voice of indescribable softness addressed me. “You love to investigate nature,” he said, “here is something that will interest you.” As he said this, he handed me a bluish-green sphere, somewhat gray in places, which he held between his index finger and thumb. It seemed to me about an inch in diameter. “Take this mineral,” he continued, “test it, and tell me what you have found. Behind you is everything that you need for such investigations, as complete as possible; I shall go off, and return when you are through.”

Looking around, I observed a fine room with instruments of every kind, which seemed less strange to me in the dream than afterward when I awoke. I felt as if I had been there often, and I found what I needed as readily as if I had prepared everything in advance myself. I inspected, felt, and smelled the sphere several times; I shook it and listened to it as if it were an eaglestone; I brought it to my tongue; with a clean cloth, I wiped off the dust and a kind of barely perceptible coating; I heated it and rubbed it on my sleeve for its electricity; I tested it on steel, on glass, and on magnets, and determined its specific weight, which was, if I remember right, between four and five. From all these tests I could see that the material was worth rather little, and I remember, too, that as a child I had bought spheres of the same kind, or at least not very different, at a price of three for a penny at the Frankfurt fair.

I turned now to the chemical tests and determined the components of the whole in percentages. Here again I found nothing special. There was some clay, approximately the same amount of lime, but much more silica, and finally some iron and salt and an unknown substance, which had many characteristics of known substances but nothing peculiar to itself. I was sorry that I did not know the name of the old man. I would have liked to name the substance after him on the label in order to pay him a compliment. I must have been very exact in my investigation, for when I added up all that I had found, it came to exactly a hundred. I had no sooner made the last stroke in my calculations than the old man stepped into the room. He took the paper and read it with a gentle, almost imperceptible, smile, and turning to me with a glance of celestial benevolence mingled with seriousness, he asked: “Do you know, O mortal, what it was that you tested?” His whole tone and manner of speaking clearly announced a supernatural being.

“No, immortal one!” I cried, prostrating myself before him, “I do not know.” For I dared no longer allude to my slip of paper.

The Spirit: Know then that it was, on a reduced scale, nothing less than—the whole earth.

I: The earth? Great God eternal! And the ocean and all its inhabitants, where are they then?

The Spirit: They are in your napkin where you have wiped them off.

I: Oh! And the atmosphere and all the splendor of the continents?

He: The atmosphere? That must still be in the dish with the distilled water; and your beautiful continents? How can you ask that? They are all an imperceptible dust; some of it is still on your sleeve.

I: But I found not even the smallest trace of the silver and gold that keep the world going.

He: Too bad. I see I must help you. Know that with your flame you have split off the whole of Switzerland and Savoy and the most beautiful part of Sicily, and you have ruined completely and overturned a large piece of Africa over a thousand miles square, from the Mediterranean to the tablelands. And there on that glass—oh! they have just slipped off—lay the Cordilleras, and what you saw a moment ago in cutting the glass was Mount Chimborazo.

I understood and was silent. I would have given nine-tenths of the rest of my life if I could have restored the earth that my chemistry had destroyed. To ask for another one, in the face of such a being, that I could not do. The wiser and nobler the donor, the harder it is for a poor, sensitive man to ask for a gift a second time, as soon as he realizes that perhaps he has not made the best use of the first. But a new request, I thought, this trans-figured paternal face will surely allow me: “O great Immortal Being!” I cried. “What thou art I know; it is in thy power; enlarge for me a mustard seed to the thickness of the whole earth and allow me to investigate its ridges and strata until the germ develops, merely to see it transform.” “What good would that do you?” was the answer. “On your planet you already have a granule, enlarged for you to the thickness of the earth. Test it. Not before your own transformation shall you come to the other side of the curtain, whether you seek it on this or another granule of creation. Take this purse, test what is in it and tell me what you have found.” In departing he added half jesting: “Understand me right; test it chemically, my son; I shall be away longer this time.”

Advertisement

How happy I was when once again I had something to investigate, for now, I thought, I will be more careful. Be careful, I said to myself, it will shine, and if it shines, it is surely the sun or a fixed star. When I opened the purse, I found, to my great surprise, a book in a rather plain, dull binding. Its language and script were none of those which are known to me, and although the characters of many lines, when seen casually, appeared to be legible, they turned out, when looked at more closely, no more so than the most complicated letters. All that I could read were the words on the title page: “Test this, my son, but chemically, and tell me what you have found.” I must confess that I felt perplexed in my grand laboratory. How? I asked myself, how shall I investigate the contents of a book chemically? The content of a book is its sense, and chemical analysis here would be the analysis of rags and printer’s ink. When I had reflected for a moment, my mind suddenly brightened, and with the light came an irrepressible blush of shame. Oh! I cried, louder and louder. I understand, I understand! Forgive me, Immortal Being, O forgive me! I grasp thy kind reproof; I thank the Eternal One that I can understand it!

I was indescribably moved, and I awoke.

(translated by Meyer Schapiro)

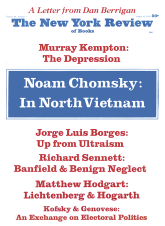

This Issue

August 13, 1970