In response to:

The National Petition Campaign from the June 4, 1970 issue

To the Editors:

“Many radicals…gag on such a strategy,” the Genoveses write [NYR, June 4, 1970] of their National Petition Campaign, as if it were a virtue. Well might such radicals “gag,” for they perceive, as the Genoveses apparently do not, that the Nixon invasion of Cambodia, coming on the tail of five years of Johnsonian credibility gap, has done much more than merely create what the authors term “a constitutional crisis.” The invasion has indeed produced a crisis, but least of all is the nature of that crisis “constitutional.” On the contrary, what the invasion has done is to raise the crucial issue of the real nature of American government and its lack of susceptibility to popular control. By demonstrating the bipartisan nature of the deception and duplicity practiced against the electorate, it has called into question the very legitimacy of government itself. The confidence of countless ordinary citizens in what they traditionally believed to be “their” government has been shaken as nothing else in the last half-century has been able to shake it.

Members of the Establishment and their representatives realize this full well, as do those radicals who instinctively “gag” on the Genoveses’ petition campaign; and it is precisely for this reason that Establishment spokesmen have labored incessantly of late to create a facade of government responsiveness to the popular will in a case where the latter clashes with the long-run interests of the corporation-based ruling class. Thus countless elite (and some not so elite) universities are providing their students with time out of classes, both now and in the fall, on the understanding that such time will be spent, as the phrase has it, “working within the system.” That those who support the perpetuation of corporation capitalism, as well as those who remain under illusions about the nature and functions of its political institutions, should endorse these efforts to divert opposition to the war in Vietnam into acceptable channels is, of course, readily understandable. That they should have the backing in this of ostensible radicals, who presumably view established government as an instrument of class rule, is simply incomprehensible.

Yet the National Petition Campaign proposed by the Genoveses can only have the effect of encouraging large numbers of confused and uncertain people to continue regarding the organs of government as fundamentally legitimate and based on the popular will. That being the case, for the petition campaign to be supported by large numbers of radicals would constitute an unmitigated disaster, a gigantic step in the wrong direction taken at just the time when many citizens are finally beginning to wonder whether the slogans of popular democracy, as taught in the public schools, are at all consonant with reality. When these individuals are then urged—and urged by those who call themselves radicals, at that—to lend their efforts to a petition campaign aimed at the Congress, rather than deepening their doubts and misgivings, this will lull them away. It ought to go without saying that the real task facing radicals in this period is not to dispel such gut-level suspicions, but to explain in concrete detail why they are more than amply justified. Petitions to Congress are bound to have exactly the opposite outcome.

For radicals, therefore, the arguments advanced by the Genoveses for their Petition Campaign can all be shown to be spurious. They assert, for example, that the campaign can create “a link between community and campus.” To be sure. But however desirable that link (and it is desirable), there is absolutely no reason in the world why it has to be made to depend on a petition campaign to Congress. Students and faculty do not have to have a petition in hand before going door-to-door in the community. It would be far more worthwhile and germane, in this situation, to use this opportunity to invite the community to a series of lectures, seminars, and discussions that dealt in depth with those aspects of American capitalism that make such wars of counterrevolutionary intervention a recurrent feature of the political landscape. In the process, to judge from the campus support that the National Petition Campaign appears already to have attracted, both students and faculty themselves might learn a good deal about how the stability of capitalism in this country has historically been predicated on endless overseas expansionism, the consequent assumptions under which US foreign policy is conducted, and the nature of real political power in this country. From the rash of working-within-the-system projects that have erupted during recent weeks, this segment of the community needs the lessons as acutely as any other. In the course of such lectures and discussions, it should be possible to arrive at some more realistic notion of how the war is to be stopped (or even shortened), beyond merely another futile and energy-consuming petition to Congress. It may be objected that to arrive at such an understanding will take time. We agree. We also think, however, that it is by far preferable that large numbers of people gain an understanding of how this society operates, even if in so doing they are temporarily inactive, rather than committing students and faculty to dashing off in yet a new round of mindless activism that does nothing to enhance their understanding. And it is just this latter that the Genoveses’ petition campaign gives every promise of being.

Advertisement

Equally pernicious as this mindless activism is the implicit support that the Genovese petition gives to electoral politics conducted along inherently liberal lines. “If it is true that the events in Congress…are of major importance to the peace movement,” the authors write, “then it follows that everything possible must be done to bring popular pressure to bear in support of a general confrontation of Congress with the President.” Given the premise, the conclusion is inescapable. But the premise itself is fatally flawed. “Events in Congress” are not “of major importance”—not, at least, to the radical wing of the movement. To focus on Congress is to invite near-certain catastrophe. For Congress will remain unwilling to force a confrontation with Nixon so long as he appears to have the backing of the bulk of the ruling class, which at present he does. The tactic advanced by the Genoveses, however, is devoid of any class analysis—it simply takes all the stock notions of liberal democracy at face value. Its logical culmination can therefore only be an attempt to make Congress “more responsive” by “changing” it through the election of so-called “peace candidates.” This, then, is where the Genoveses’ petition campaign promises to lead us in practice (as has indeed emerged after this letter was written). One would hope that more than a decade of experience with such “peace candidates”—including Johnson in 1964 and Nixon (who had “a plan to end the war”) in 1968—would have demonstrated the utter irrelevance and futility of efforts at working through electoral politics for a US withdrawal from Southeast Asia.

Moreover, even if it were true that “everything possible must be done to bring popular pressure to bear in support of a general confrontation of Congress with the President,” it scarcely follows that the best tactic is that of the petition campaign suggested by the Genoveses Whether Congress can or will respond to a deluge of petitions is eminently debatable; what is not debatable is whether Congress will respond to the fear that the continuation and expansion of the war in Southeast Asia is making the country literally ungovernable by the usual parliamentary methods. None of the measures (Cooper-Church, Hatfield-McGovern, etc.) currently pending in Congress was introduced simply or even primarily as the result of petitions. They were introduced because of fear that the longer the war continues, the more unstable the social order at home becomes. If this analysis is correct, it should be quite evident that Congress will be much more likely to act to restrain Nixon if it appears (as it did in the immediate wake of the Cambodian invasion) that only through such action can there be any hope of avoiding massive turmoil and perhaps even open civil warfare. It would seem, therefore, that methods that are both more direct and more vivid than a petition campaign could be found for conveying this point to the Congress in a way that would permit no misunderstanding. Radicals may well wish to give serious thought to devising such methods!

Liberals, naturally, will not agree with this analysis; they will wish to support such respectable tactics as more petitions and more “peace candidates.” Radicals will not be able to prevent liberals from throwing their efforts in this direction; but that is no reason why radicals should encourage liberals, much less join forces with them, in a movement based on liberal rather than radical assumptions. Instead, if radicals are sincere about wanting to stop the war and beginning the reconstruction of American society, the best thing they can do is to point out to the liberals at every step of the way why conventional electoral tactics are doomed in the end to fail. In this way, and only in this way, can the most committed liberals be won over to radical political action. But if radicals insist on abandoning all their supposedly sophisticated class analysis of capitalism to trail after liberals in further parliamentary maneuvers, the results will be just the opposite: the war will continue unabated, and worse yet, many liberals, discouraged by their initial failures, will thus drift back to passivity and inactivity, as for that matter will radicals who have become confused and demoralized from being shoved into fruitless liberal adventures by radical theoreticians to whom they looked for guidance. The only winner thereby will be Nixon, who will emerge with a free hand to do as he pleases once more. Hence through the default of the radicals when it comes to putting their theory into practice, the peace movement will again be shortchanged of its goal: the ending of the war.

Advertisement

Nixon, by his invasion of Cambodia and his lies about ending the war, the US role in Cambodia and Laos, etc., has opened a wedge between a large segment of the American public and himself. It is the imperative duty of serious radicals to bend every effort toward enlarging that wedge, by an analysis that makes transparently clear to as many citizens as possible that existing political institutions are so structured as to be able to reflect only the class hegemony of the corporate rich rather than popular sovereignty. In this situation, to call for any tactic that has the effect of leading people to look to these same institutions for an end to the war is nothing short of a betrayal of the meaning, the purpose, the objectives, and the immediate task of contemporary American radicalism.

Frank Kofsky

Sacramento, California

The Genoveses reply:

Mr. Kofsky does us too much honor. The National Petition Committee is not the Genoveses’ in any sense—although one of us briefly served as secretary: It was established by liberals and we have supported their initiative. That we said clearly in our original letter, and might, therefore, wonder why Mr. Kofsky chooses to pretend otherwise. But, in fact, we suspect we know why. We argued that radicals should support the NPC and work through it as best they could because the Left offered no sensible alternatives.

Mr. Kofsky, however, does have an alternative. We should, he says, have had an Alternate University to which the community would have been invited and which would have taken up basic questions in depth. Strange, we have done just that—as we also made clear in our letter.

Mr. Kofsky says that the “constitutional crisis” is really a social crisis. Yes. But that was our point.

Mr. Kofsky says that to fight on Congressional terrain is pointless since Nixon’s policy is that of the ruling class. We hate to challenge him, but we should like to see proof. Our position is that the ruling class is split and that Nixon may well speak for its minority. Our position is also that any serious American Left must take account of the legitimate respect of the working class for democratic institutions—that very Congressional terrain.

But all this shadow-boxing obscures what really seems to be at issue. Mr. Kofsky seems to think that many on the Left—if it were just the Genoveses he would not care—are fed up with revolutionary hallucinations and are determined to effect an alliance with leftward moving liberals and social democrats to build a democratic socialist movement. He is a bright fellow, and naturally we are embarrassed to be caught with our hands in the cookie jar. It is too late to deny it. We are guilty.

We are also guilty of thinking that those who continue to prate about a present or foreseeable revolutionary situation in America are in danger of committing the one sin for which no radical may ever be forgiven: that of completely misunderstanding the country in which they live and therefore of becoming tiresome. Still we do not wish to deter them. You imply, Mr. Kofsky, that a revolutionary solution is possible for America. Very well. Hic Rhodus, hic salta!

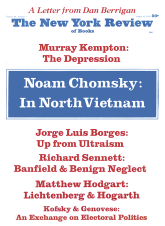

This Issue

August 13, 1970