What were the major educational changes during the Sixties?

Some of the major assumptions, many of the practices, and most of the myths of higher education were badly shaken. There is no doubt that some transformations took place. There is considerable question, however, whether the transformations provided the foundation for anything enduring.

At many institutions the traditional curriculum has been greatly modified or abandoned in favor of more “experimental” courses. Apart from the occasional vice of promoting non-courses, experimentalism has mainly meant things like encouraging students to initiate courses or to share in formulating them; placing less emphasis upon grades or devising new symbols of performance; adopting an open-minded view of what will be acceptable as “work” in a course; and, in general, making it possible for students to choose the mode and pace of their studies.

The virtue of experimentalism is to have recognized, and to have attempted to break with, the passive character of the “educational process,” as it is called, at most institutions, especially at the larger ones. This is a step forward, as virtue usually is, but hardly a revolution. Above all, it evades rather than confronts the great change which has come over the students of the Sixties and which is expressed in their hostility toward curricula designed to prepare them for a “place” in the job structure of society. Many able students plainly want no part of what America has customarily offered its college graduates. Although experimental courses tend to reflect this anti-vocationalism, they also tend to exacerbate the powerlessness which is the lot of those who renounce a vocational calling.

“Student participation” was another of the novelties of the period. The most controversial questions here centered around the matters of faculty appointments and promotion, student admissions, and degree requirements. Now that rhetoric and passions have subsided, it can be clearly seen that neither the great hopes of the challengers nor the great fears of the defenders have been fulfilled.

The most explosive possibilities of “participation” appeared in the controversies surrounding the establishment of black studies programs or departments. There was an evident split between those blacks, on the one side, who looked upon the programs as a way of introducing a neglected subject matter and altering the racial composition of faculties and student bodies and, on the other side, those who conceived the programs as training camps for activists and staging grounds for struggle in the ghetto. It is too early to judge which, if either, of these elements will win, or whether they will remain in tension. It is also too early to determine whether blacks will insist on segregating their programs and personnel, thereby consolidating independent enclaves within the universities, or whether they will consent to one or another form of integration. However this comes out, a truly profound change in American society will have taken place only when black youth can look forward with the same confidence as white youth to college attendance as an almost normal part of growing up.

If there was any one change in American higher education that was visible to all observers, it was the increasing politicization of the campuses. We have already treated this matter at some length in other articles in The New York Review,1 and here we shall only consider why politicization has evoked such widespread apprehension and misgivings. The most common charge is that political activity contaminates the search for truth and jeopardizes academic freedom. Politics means partisanship and partisanship is the enemy of truth.

Rather than attempt to argue that the notion of academic freedom needs to be revised and that revision must be preceded by a more searching inquiry into the nature of politics and of political education, we shall only suggest that in large measure the fears about politicization of the campuses arise out of an unduly narrow conception of politics. This conception faithfully reflects the narrow terms in which Americans have typically talked about and practiced politics. That mode of thought and that practice are major contributing factors to the present crisis of American society.

In America, politics means bargaining and compromise between organized groups for limited and usually material prizes. To most citizens, it means periodically choosing between one or another moderate candidate and one or another blurred issue. Even though the stakes are limited, the rules of the game are many and confining. Hence, small novelties look like major violations. When new actors appear, e.g., blacks or students, employing new tactics and language, and pursuing “ideal” goals, intense fear and hostility are aroused. Such departures are viewed as radical, not because they necessarily are, but because politics itself has been so narrowly conceived, so tightly drawn, that innovation appears as revolution. Americans have always been hospitable to economic innovation but in recent times they have become increasingly suspicious and fearful of creativity in the political realm.

Advertisement

Perhaps the most discussed change on the campuses during the decade was the appearance of that troublesome companion of politics, violence. It is worthwhile remembering that violence was not a part of student politics in the beginning—in fact, it hardly appeared before early 1968. Since then, it has continued to grow.

In order to understand the growth and significance of violence in student politics, it is necessary to distinguish the violence which is overt, spontaneous, and committed by large numbers of people employing mainly the force of their bodies, from the violence which is covert, calculated, and perpetrated by a small handful using manufactured weapons. This latter form of violence, properly called terrorism, is a familiar historical phenomenon. Sometimes it is the expression of personal pathology, and sometimes the product of a totally despairing analysis of the possibility of significant social change. The United States has experienced terrorism before (e.g., by anarchist assassins, Ku Klux Klansmen, and Molly Maguires) but what is disturbing about the new terrorism is that it is done by young people. Furthermore, this terrorism is justified in some quarters (e.g., Weathermen) by an ideology brewed from domestic American ingredients. The new terrorism, in short, cannot be dismissed as the work of foreign fanatics inspired by alien doctrines. It represents the last stage of the despair of the young with America.

The mode of violence which we have described as overt, unpremeditated, and collective is closely connected with, even an outgrowth of, the new politics spawned on the campuses—a politics which responds to different rhythms, pursues different ends, and is communicated in a different language from conventional politics. It is pulsating and kinetic, contemptuous of compromise and impatient with routines; and it threatens always to overflow customary channels. It sees victory as something gained by energy and exuberance rather than cunning. Like its insistent music in the background, it is shaped toward a climactic moment. When it encounters certain obstacles, its gathering energy is ready to explode. When confronted by abstract rules and policies, by stolid and anonymous agents of authority, by the rituals which civilized society contrives to defuse passion, it is ready to spill over into provocative and destructive acts.

What are the conditions which produce this kind of violence? In part it arises out of frustrating encounters with a cumbersome and unresponsive system. The frustration grows as the new politics increasingly differentiates itself from the established practices. The system thus appears increasingly unresponsive—not necessarily because it in fact is, but because its challengers have sharpened the distinctions. Eventually the point is reached where the system may in fact respond but the challengers cannot recognize it—just as the system managers may find no sense in the antics of the challengers.

In part, too, this kind of violence is a reaction to the drabness of American politics, a reaction natural in a generation which loves whatever is dramatic, colorful, and provocative. Perhaps (as the cliché goes) we are a violent people; but maybe that is because we have increasingly become a politically unimaginative and conservative people. We now congratulate ourselves on the fact that we are the oldest, most continuous—and therefore—most stable democracy in the world. Violence is a protest against pedestrian politics and stale rhetoric. It becomes a means of turning politics into drama.

Although some of the overt and spontaneous campus violence may be explained by the usual categories of “mob psychology,” and although some of it is the work of petulant and spoiled kids, and some more of it originates in black frustration and rage against a white world, it is important to recognize the deeper significance of the assaults on both persons and property.

Students have not attacked the police with guns: it is difficult to find an authenticated instance of actual sniping, much less a case where a student sniper has been convicted in a court of law. They have used clubs, rocks, and their own bodies as weapons. When students assault police, the physical contact becomes a way of asserting that there is a human reality to the world, that the world is not all plastic and steel. If, in Hegel’s world, the master and the slave needed each other, in our world perhaps the cop, sealed within his battle jacket and shielded by his visor, needs the student as much as the student needs him.

The mounting assaults against property are correlated with significant changes in the nature and meaning of property. Younger generations have been brought up in a world of replaceable and disposable objects. Property has lost its associations with permanence and stability, just as it has long since lost any direct connection with labor. Important property is institutional property—which is to say the main forms of property are associated with the main forms of power and authority in our society. In either case, whether property is viewed as replaceable or as institutional, it loses sanctity.

Advertisement

The most worrisome aspect of student violence is that it is increasing, which means that it threatens to become an integral part of the new politics; if not a constant feature, then at least an immanent possibility. Student activists, while reluctant to use violence, have been equally reluctant to condemn their “allies” who do use it, be they Angels, Crazies, or Panthers. A certain dulling of sensibilities is bound to result, a loss of sureness about what is morally intolerable. This will lead inevitably to brutalization, to viewing the enemy precisely as he is said to view you: as an object.

Shortly after our last essay in this journal was written, American soldiers invaded Cambodia and National Guardsmen killed four students at Kent State University. The campus response was prompt and passionate—the most powerful expression to date of the new politicization.

Cambodia provoked a genuine political uprising on the nation’s campuses which has left a range of consequences whose full effects have not yet been fully registered. During the first week of May, about 500 campuses shook off ordinary routines to express their shock and outrage. An uneasy academic year erupted in a storm of political activity. “Before Cambodia,” ran a recent memorandum to the President, “many of us on the campuses believed that deep disaffections afflicted only a small minority of students. Now we conclude that [Cambodia] may have triggered a vast pre-existing charge of pent-up frustration and dissatisfaction.”

The responses were astonishing. Secretary of State Rogers confessed, with proper diplomatic understatement, that the Administration had not fully anticipated the campus reaction to the invasion. Equally astonishing was the response of politicians and campus officials. With virtual unanimity, college administrators gave ground. They relaxed the normal rules governing academic routines and campus facilities. Several even expressed their sympathy with the antiwar sentiments of the students. National and local politicians were less unanimous, for they had to contend with the fears and hatreds of Middle America which for the past quarter century they had done so much to create. Even so, many politicians urged students and faculties to exert pressure on the government, especially in the campaign to limit the war powers of the President.

More astonishing still was the speed of the about-face of the President and his advisers. They were compelled to repeated justifications of the invasion, justifications so transparent that the public was given an unparalleled opportunity to watch a myth being manufactured. So intense was the pressure that the President soon had to promise that American troops would be pulled out of Cambodia on a specific date. More important, he had to keep that promise, despite the risks. Rarely if ever in American history has a President reacted so hurriedly to a wave of public sentiment and reversed a policy. The reversal was dangerous because it involved a pre-announced military retreat accomplished in full view of the entire world and against the opposition of some of his own military men. The reversal was also difficult politically, because it touched strong popular emotions of patriotism and national pride.

This heady experience of campus power may obscure the special circumstances which made it possible and blind the campuses to the gathering political dangers. Even if we grant what is not at all self-evident, that the termination of the Cambodian intervention marks a decisive turn toward disengagement in Indochina, the fact remains that a unique conjuncture of circumstances made the result possible. The power of the antiwar forces in the Senate was cresting while popular support for the President’s Vietnam policies was temporarily ebbing. Such a fortuitous conjunction might occur again, but the fact that the success of the campus protest depended upon it demonstrates that its potential falls far short of being revolutionary.

That the campuses had such potential was once an illusion of the radical left. Unfortunately, it is now becoming an illusion held by an ever-increasing number of citizens of all classes and promoted by politicians of both parties. We may even now be moving from a period dominated by the one illusion to a period dominated by the other, the illusion that since a revolutionary peril exists, harsh and systematic measures are therefore needed. Although there have been specific instances of severe force being applied against campuses, there seems as yet no determination on the part of the Nixon Administration to mount a sustained attack upon higher education. Nevertheless, the present campaign against the Black Panthers, as well as the past experience of heresy-hunting, argue that political suppression is not an unthinkable possibility. There is, however, one important difference between suppressing campus political activity and suppressing Panthers, Communists, and alleged faculty “Reds,” a difference which presents certain difficulties to policy-makers. The society needs campuses in a way that it does not need Panthers and leftists. As Professor Teller, an archenemy of the new politics put it, if campus disturbances continue, “in 20 years, the United States will be disarmed.”

If a systematic campaign were to be launched against the campuses, certain elements would have to be present in combination. What would the profile of such a campaign look like? First, there would have to be a demonstrated willingness to apply police and/or military force against the campuses and to apply it quickly, often, and disproportionately to the actual threat. Second, there would have to be politicians ready to define themselves primarily by their hostility toward higher education, in its intellectual as well as its political aspects; ready to make that hostility a fundamental feature of their electoral campaigns and daily rhetoric; ready to initiate policies or legislation patently designed to injure the operation, development, and morale of campuses and to restrict traditional faculty prerogatives; ready to provoke or maintain campus unrest, thereby proving to the public that a revolutionary conspiracy exists; and careful not to cripple so vital a national resource as the campuses, only to render them docile and powerless.

This combination, in which repression provides the stuff of a political dynamic, does not exist in Washington at the present time. The backlash to Cambodia has produced instead some conciliatory gestures, such as the appointment of Alexander Heard as a temporary Presidential adviser, the creation of a Commission on Campus Unrest, and the acknowledgment that, at times, the rhetoric of the Vice President and Attorney General may have been a bit much. Although nothing profound is likely to happen as a result of any of these moves, they hardly suggest anything ominous.

But in one part of the country the combination of anti-university elements is in active operation. Since 1967 California has been governed by an administration which has perfected the art of using the universities for political advantage. The dynamic of the Reagan administration depends almost entirely upon its ability to sustain public anger against education. In this way not only is he assured of solid public support for his periodic attacks on higher education, but he is also enabled to distract the voters’ attention from welfare programs, taxes and revenues, primary and secondary education, and boondoggles like the one of converting the Queen Mary into a tourist attraction.

The Reagan administration may have given the illusion of being little more than a Hollywood creation, but behind the appearance is a sure instinct for power. Nowhere is this displayed more clearly than in Reagan’s open domination of the Board of Regents, the supreme authority of the nine-campus university system. The Governor’s control over the Board is best summarized by the Board’s voting patterns. On any matter involving political controversy, be it finances or personnel, he can usually count on a majority of 20 to 4, rarely less than 17 to 7. As now constituted, the Board is deeply conservative and representative mainly of great corporate power and its auxiliaries in public relations, advertising, and the law. The composition of the Board has pretty much been this way for many years. What is new is not the presence of conservatism on the Board, but the disappearance of that possessive and paternalistic affection toward the University which used to temper regental outbursts. Several Regents plainly do not like the University or its employees.

In the old days Regents used to contend fiercely with governors and legislators over the budget of the University. Now, however, it is a fairly predictable process. It runs like this: the Board prepares its budget and the Governor prepares his. Since the Governor is, at the same time, a member of the Board and since most of its influential members are his appointees, it is fair to say that neither party is very much in the dark about what the other is prepared to concede. Every year the charade is played out and the financial plight of the University steadily worsens, its construction plans halted while student enrollment pressures rise, its faculty salaries lagging well behind those of comparable institutions, until the only promising solution appears to be the one rumored about: that the Regents are thinking of selling a couple of campuses.

It is clear that, during the Sixties, the Regents have lost the autonomy which the California constitution intended they should have. 2 As a result, they have become a conduit of, rather than a buffer against, hostile political forces.3 Their role as guardians of the financial needs of the University has been subordinated to that of an agency for carrying out the politico-fiscal policies of the Governor. 4 The Board of Regents has become incorporated into the political plans of the Reagan administration.

In surveying the actions of the Regents over the past few years, one is tempted to describe them as counter-revolutionary, except for the fact of a revolution which never materialized. Nonetheless, believing that they are combatting revolutionary movements and conspirators, the rulers of the university system have struck at most forms of hopeful change and destroyed or threatened some traditional practices—traditional, that is, at decent colleges and universities. The first major step toward pacification of the campuses was in 1968. The motivation behind it was plainly political. Eldridge Cleaver delivered several lectures in an experimental course held on the Berkeley campus. The Regents declared that academic credit could not be given for the course, even though the course was well under way. They went on to reverse their own well-established principle by which the faculty had been granted authority over curriculum, course credits, and the use of “guest lecturers” in a course.

The Board’s next step was to fire faculty members on political grounds, even if it meant violating their own rules. The perfect test case was provided by a young philosopher who had been teaching on a temporary basis and was now about to be offered a regular appointment. The philosopher, Angela Davis, was female, black, an alumna of Brandeis, a student of Herbert Marcuse (who was about to have his own annual reappointment blocked by the Regents), and an avowed Communist. In order to prevent the appointment, the Regents had not only to reject a recommendation from the faculty, but they had to violate their own rules—first, by taking the final disposition of the case from the office of the UCLA Chancellor, where normally it would have been concluded, and, second, by ignoring their own resolution which forbids firing faculty members because of their political views.5

All of these complicated maneuvers were prompted by the fact that when the Regents had first discharged this same philosopher, a Los Angeles judge had held that she could not be fired for political reasons. The Regents have won a motion to have the case transferred to another jurisdiction. Such are the whimsies of the law-and-order mind that one is led to believe that the main difference between the campus rebels and the Regents is that the students break the rules, while the Regents merely change or evade them.

The cynical disregard for the spirit of legal forms is not a peculiarity of California conservatism. We have seen the defenders of law and order prosecuting the Chicago Seven, hunting down the Panthers, and pushing what the President recently called “the necessary strong methods” of quick entry and preventive detention. Doubtless the President was being sincere when he said that “repression…is not a government policy,” just as the Regents doubtless believe that their recent resolutions are individually tough but not the collective product of a policy aimed at eliminating academic freedom and prerogatives. The predictable result in both cases will be a further decline of authority. Those in high office fail to understand that their own legal lawlessness promotes both the lawlessness they abhor and the political disrespect which feeds so much of the present lawlessness.

Following the campus furor over Cambodia the Regents again began to challenge faculty prerogatives. In July, 1970, a few Regents succeeded in temporarily blocking two faculty promotions, one involving tenure for a young faculty member who had been active in moderate left politics on the Berkeley campus (and who was defended by the Berkeley Chancellor for being a restraining influence), the other a promotion to full professorship for the chairman of Miss Davis’s department. At this same meeting the Regents singled out two professors, well-known for their highly conservative views, and granted them exceptional salary increases, thereby prompting one Regent to remark, “We are blocking liberal professors and voting raises for conservatives—how much more political can we get?”6

The answer to the last question is, quite a bit. The Regents have made it clear that they are determined to impose tighter “discipline” on the faculty. In this task they have found a willing agent in Charles Hitch, the University’s president. According to the latter, the present system of voluntary adherence to a code of faculty ethics has not worked because faculty committees have mistakenly assumed their “main duty to be that of defender of all the rights of the faculty member without a corresponding degree of concern for the welfare of the University” (i.e., such committees have blocked local chancellors in their attempts to fire faculty members for political reasons). He has called for the rules to be revamped so as to prevent teachers from altering course content or from rescheduling courses for political reasons. He has also asked for greater administrative voice in curriculum and course content to protect the “academic freedom of students” by screening out “extraneous subject matter” or “irrelevant discussion.” “We are,” he noted without irony, “experiencing new pressures.”

The recent actions of the President suggest another change of great historical significance. During his presidency Clark Kerr had always managed to preserve considerable autonomy by attracting strong faculty loyalties. But his successor has become wholly dependent on his employers. This historical shift in the President’s power was clearly recognized at the Regents’ meeting when the President brought in his proposals for faculty discipline. According to newspaper accounts the proposals were received “enthusiastically.” One Regent called it “a brave first step” and another suggested that the Regents might some day have to take away all of the Academic Senate’s authority “and give it to the president over whom we have control.”

The time span of these events does not stretch over several years but is compressed in a short period. Moreover, the pace is quickening and the Regents’ offensive is spreading. At their July, 1970, meetings the Regents instructed the chancellors to prepare measures for eliminating “socio-political advocacy” and “the dissemination of lewd, obscene [a bit of California overkill] articles and photographs” from student newspapers. Failing such measures, the Regents promised to cut off all funds to the papers.

When the Berkeley faculty voted to modify ROTC programs, the Regents’ response was to approve a resolution to explore the possibility of introducing ROTC units at the four campuses which do not now have them.

After the Berkeley faculty had voted to request the termination of the relationship between the campus and two laboratories which, according to an official report, “encompass every aspect in the process of developing nuclear weapons,” and over which the campus had virtually no control, the Regents passed a resolution (July 17, 1970) reaffirming the importance of research for national defense and vowing to continue to sponsor such programs.

What all this adds up to is not a series of attacks, but a roll-back which threatens the modest measure of academic freedom previously enjoyed and promises a greater increase of bureaucratic controls. It represents, too, a denial of all that has happened, not only at Berkeley but throughout the country, between 1964 and 1970.

The picture is made all the bleaker by the progressive demoralization of the faculty. Bugged by students, assailed by Regents, surrounded by a hostile citizenry, feeling the pinch of shortages in research funds and of salary increases denied, they, along with their colleagues at the other campuses, have begun to show signs of capitulation. Not even the mildest protest was registered against the Angela Davis decision by the Berkeley faculty; and even the UCLA faculty has begun to retreat. More ominous, there are signs that an organization of faculty members is being formed to seek ways of ridding the campuses of faculty troublemakers, even if they are tenured members. As one of their spokesmen put it, the position of the academic community is much the same as that of the business community in the Thirties: it has developed abuses which it cannot remedy by itself and hence government intervention is justified.

At this juncture it is difficult to predict how long and how far the present dynamic will go in California. Recently it sputtered slightly when some state legislators demanded an inquiry into alleged improprieties involving the borrowing of University funds by a powerful Regent. Shortly afterward another disclosure hinted at some dubious relations between certain Regents and a land development company working on one of the local campuses. When one of the Regents charged that the Board had “ducked the issue” about the company “because some people have been caught with their hands in the cookie jar,” and when he raised questions about the improprieties referred to above, the Board quickly moved on to other things.

But the most immediate question for the campuses in California and elsewhere is, after Cambodia, what? In his memorandum to the President, Chancellor Heard had struggled to shake Mr. Nixon and his advisers by describing the situation as “a national emergency” which “we do not believe that our national government really understands.” That lack of understanding was confirmed by the cool reception accorded Heard’s eloquent statement.

The most striking, if inadvertent, testimony to the chasm separating the thinking of our national leadership from that of the student generation was contained in a report (July, 1970) by the President’s National Goals Research Staff. Its conclusion is a classic statement of the current malaise, for it declared that the President cannot set goals for America. Instead he should provide information so that society can debate what it wants. “A national growth policy” would somehow “evolve in varying pieces,” but, thanks to the dynamic nature of events, growth “will probably never be completed” during the Seventies. Somehow, too, it did not seem to worry the NGRS that it had provided a longwinded confession that the highest office in the land could not formulate some vision of the future—a failure which was also explained by the “political” consideration of what the Democrats might do if they were supplied with norms for appraising the President’s performance. The Report deliberately avoided any discussion of national goals involving such problems as racism, foreign policy, the plight of the cities, or political suppression.

The most characteristic response to the chasm has been to try to bridge it by assimilating student activism into the structure of traditional pluralistic politics. This was the response embodied in the “Princeton Plan” for encouraging summer political activity and promising a moratorium on classes during the final two weeks of the electoral campaign in the fall. Although many students eagerly welcomed the chance to work for the parties or candidates of their “choice,” many of their elders took the cooler view that contact with the “real world” would prove sobering. So during the summer students cut their hair, shaved their chins, shed their jeans, lengthened their skirts—mute testimony to the politics that Americans understand and demand.

Many of the goals now being pursued through electoral politics are so eminently necessary—peace in Vietnam, reasserting constitutional control over the President, and ending racial and political oppression—that criticism inevitably seems ungenerous and obtuse. Yet there is reason to pause over the warnings voiced by some politicians and commentators that the odds are overwhelming that students will be disappointed by the results of electoral politics. This is another way of saying that the system is incapable of responding to powerful protests even when they follow orthodox lines. It is also a way of conceding that what need to be changed are not the actors but the assumptions of the system. An infusion of young blood is not going to alter things: there are always more William Moyerses than Mario Savios.

Even in the midst of the Cambodian protest widespread apprehension began to be expressed about what was likely to happen in the fall. In part there is apprehension because student politics is no longer innocent. It has begat its share of opportunists, hooligans, and ideological thugs. If internal corruption and demoralization increase or if electoral politics becomes the controlling form of “political socialization” they will pretty much end what promise there was in the Cambodian flare-up. The meaning of those events was that politics was taking hold in new places and seeking new forms. During the May and June days many thousands of students who, until then, had had little care for political things were initiated into the new politics. It is too early to assess the staying power of these new recruits or the extent of their understanding of the issues. It is also apparent, not only from the popularity of the Princeton Plan but from the fate of the New Left, that the “system” has lost little of its absorptiveness. The New Left of the past decade has seen its issues adopted by liberals and moderates and its tactics rejected by both moderates and extremists—violence is preferred by the latter, electoral politics by the former.

It remains to be seen whether the crisis of the spring of 1970 amounted to a critical experience which could launch a whole new generation of political activists and a whole new style of political action. A few voices did rise above the anxious but self-congratulatory din of the new converts to the antiwar cause and tried to call attention to the profound crisis in the state. A few others tried to call teachers and students to the large task of redefining the aims and structures of higher education so that we might produce educated men for whom knowledge, personal identity, and public commitment are part of the same quest.

Something new took place on the campuses after Cambodia, but in our day it is the special fate of novelty, even extraordinary novelty, to pass quickly and be forgotten. “I had hoped,” one of the astronauts wistfully remarked a year after the moonlanding, “that the impact would be more far-reaching….” It may be that the campus effects of Cambodia will be comparable in the long run to those produced by the civil rights movement. It may also be that the aftermath of Cambodia will confirm that we are truly in an iron cage.

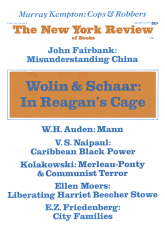

This Issue

September 3, 1970

-

1

See NYR, March 11, 1965; February 9, 1967; June 19, 1969; October 9, 1969; May 7, 1970. A collection of these essays including the present one will be published in October by The New York Review under the title The Berkeley Rebellion and Beyond.

↩ -

2

Article IX, section 9 of the constitution establishes the Board of Regents. It contains the following: “The university shall be entirely independent of all political or sectarian influence and kept free therefrom in the appointment of its Regents and in the administration of its affairs .”

↩ -

3

Occasionally the politics of the Regents is expressed amusingly, if spitefully, as when they refused to award an honorary degree to Mayor Lindsay. Berkeley faculty responded by awarding the mayor a citation.

↩ -

4

The most vivid illustration occurred during the maneuvering over the 1967-68 budget when the Regents ended up appropriating nearly $25 million from their own special funds to round out an austere budget. The issue is not that universities ought not to dip into their own funds during periods of fiscal troubles, but rather that in this instance the Regents were abetting the generally punitive fiscal policies of an Administration bent on redeeming its campaign rhetoric at the expense of education, welfare services, and medical services. See the account of this dispute in V. A. Stadtman, The University of California, 1868-1968 (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970), pp. 493-95.

↩ -

5

Later, the Regents declared that the firing was based on Miss Davis’s intemperate language, which was interpreted as indicative of conduct unbecoming a faculty member. This justification was produced after the actual decision had been taken. The press and media throughout the state made it public knowledge that Miss Davis would be fired well before the announcement, just as they had reported the daily development of the Regents’ argument that she was not being fired for her political views but for her deportment.

↩ -

6

On August 7, 1970, it was announced by one Regent who had blocked the promotions of (as he put it) “the two faculty described in the press as ‘liberals’ ” that the promotions would probably go through. He also defended the exceptional salary increases even though in one case neither the Berkeley Chancellor nor the Berkeley faculty had recommended it. As the Regent noted, the faculty member had “long been a colleague of mine.” What seems to have been lost in the dispute is not whether liberal faculty are punished or conservative ones rewarded, but whether the Regents have any business determining complex questions of academic competence.

↩