Stick with your friends and let something come out of that.

—Mike Nichols

It is not always easy for us, living among them, to imagine that we walk with legendary men. Still, the legends grow; tales of the new New York wits, the “new journalists” who, following the axiom that it is best to write about what interests you most, write often about themselves and each other. In this tradition, Joe Flaherty, a writer for the Village Voice, has put together a tidy book about the slobbish Mailer-Breslin run for municipal leadership of New York City—a campaign for which he was manager and which was begun in order to become legendary. Since one of the popular entertainments of New York night life has long been watching Mailer make an ass of himself, Managing Mailer is a kind of bonus; a compendium of embarrassments concerning Mailer and his gang. We can now know what happened without the pain of attendance.

It is an effect of the age of mass communication that the communicators themselves become celebrities. News programs, the press, the late-night shows give such extensive exposure to the customary celebrities, the news makers (politicians, movie stars, men who went to the moon), as to show them clearly to be, for the most part, stupid, venal, or merely boring. We must look elsewhere for superiority. Writers and intellectuals, since their business is words and ideas, come off better than most. They make judgments on decisions rather than decisions, and that gives anyone the edge on truth and wisdom. It is not surprising, then, that the new journalists would begin to think they might be superior operators in the business of running things.

These journalists, after all, know everything. Like old wives, their tools are intuition and myth. You can tell all about a man from the way his eyes shift, how he speaks to a child, what he says when he’s drunk, how he plays ball. You can measure a government from the cut of the suits of the cabinet or Middle America from a conversation in a bar in Jersey. Since writing which confirms our superstitions is agreeable, the new journalists had so much attention paid them that by the spring of 1969, it seemed the whole country or—in the case of the Mailer campaign—at least New York was ready to give all power to some of the staff of New York magazine and the Village Voice.

Getting Mailer to run for mayor that spring was certainly not difficult. It had been a wildly successful period for him; he was writing brilliantly as the uncontested star of the new journalism and he was winning the mass applause that had previously eluded him. In his public appearances, his statements from platforms, his movies, there was an extra level of hyper-manic energy superimposed on his normal elevation. Mailer had planned to run for mayor of New York once before, but blew it when, in an access of misogyny, he stabbed his second wife. Curiously, the first time around, his running for office seemed a more serious scheme. Perhaps this was because he, we, and the era were all far younger, the ideas were fresher, and we had no knowledge yet of how wild things could become.

This time, the mayor balloon was pumped up by Mailer and a group of those writers like Jack Newfield who are always seeking after the sources of power in the hope that ultimately they will find it in themselves. At a summit meeting at Mailer’s house in Brooklyn Heights, it was decided that Mailer would enter the Democratic primary with Jimmy Breslin running for president of the City Council. Gloria Steinem presciently declined to run for controller because her name on the ticket would make it look like “a campy literary exercise.”

Informed opinion within the group had it that since everyone knew what Mailer stood for (although a poll taken during the campaign showed that 60 percent of the persons polled had never heard of him), he would not only be the candidate of the elite, but might also effect a coalition between the left and the right. The latter premise was based on his running as a radical conservative who believed in absolute community control (John Birch Day in Staten Island, Martin Luther King Day in Harlem) along with such programs as no fluorides in the water and the shutting off of electric power in the city on one Sunday a month. Also Mailer understood black street culture, a nice balance for Breslin, who understood white street culture.

Breslin had first come to metropolitan prominence as a hard-nosed columnist for the old Herald Tribune. At the time of the campaign, he was in high favor as a primitive who had seen the light because after some years of hawkishness he had come out against the Vietnam war—a feat which made people think a great deal more of him than if he had been correct all along. In the campaign, it was Breslin who was to be the candidate of that common man who had neither education nor soul enough to fall within Mailer’s natural constituency.

Advertisement

The major plank of the platform was the old dream of New York City becoming a separate state, an idea that went back about a century but which was revived for Mailer by Clay Felker, the philosopher-editor of New York magazine—a possibility about as likely to be implemented as the ceding of the state of Mississippi to the Muslims.

As to the “power to the neighbor-hoods” conceit, it took on an unexpected dimension during a speech at Pace College when a woman student asked Mailer what would happen if Forest Hills decided to exclude blacks and Jews and Mailer answered that such neighborhoods would be forced to pay higher taxes. “Aren’t you saying then,” she asked, “that money can buy anything?” There was a further erosion of the attraction of absolute local control when, at a temple in Queens, an elderly Jew asked, “If their police have guns, what would stop them from coming in and killing our police?”

Almost from the start, the provo spirit of the campaign had begun to disintegrate. Breslin, who is nothing if not sane, tried feebly to remove himself from the ticket when he saw that the lark was going the way of a crusade. Only a certain schoolboy kind of honor (which conjures up pacts signed in blood with a pin) kept him going. Both Breslin and Mailer drink a lot and talk about it more. They are both so swaggering and tough-talking and dare-taking that you can’t help seeing the flesh of the past beneath the present manifestation: two plump little boys whose mothers took them very seriously. Which, I suppose, is why they expect to be taken seriously by the rest of us no matter what they do.

Especially the candidate for mayor. On the long march to Primary Day, Mailer had begun to want to be mayor and the skin he put on was that of the professional pol. Shortly before the end he even demanded such proofs of loyalty as that his aides shave off their beards and otherwise shape up for the general electorate.

Breslin was somewhat more engaging than Mailer, getting off such lines about the other candidates as “Robert Wagner keeps up with the news by reading the New York Herald Tribune.” But in spontaneous conversation he tended to revert to pre-literati type. Once, leaving an audience of Sarah Lawrence students who had not responded properly to a Mailer visitation, he yawped, “Norman, you gave them that high-class Harvard shit. I should go back in there and call them a bunch of dumb dike cunts.”

In the end, New York did not want either of them. “All Norman Mailer, the politician, accomplished,” wrote Richard Reeves in The New York Times, “was to prove that in New York City, almost anyone can get 41,000 votes if a million people go to the polls.” As anyone who has watched him over the years knows, Mailer is better read.

The distinction between the quality of Breslin’s prose and his public style is not so marked as it is with Mailer. Breslin has none of Mailer’s scope or originality—but he is often funny in the way those people are funny who think they say exactly what they think. His newspaper columns were always readable; he has a splendid ear for imaginary dialogue, a full catalogue of personal insults, a hyperbolically accurate descriptive sense, and a useful all-purpose attitude about the total corruptibility of everyone. These virtues are all evident in Breslin’s first novel, The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, but they don’t add up to so much fun when they’re hung on a creaky, old-time story.

Here is a tale of Mafia gangs at war, told in a kind of neo-Runyonese but without Runyon’s sentimental tolerance of his characters. Breslin, unlike the authors of such books as The Godfather, at least knows that even if everyone is rotten, the Mafia is more rotten than anyone else. Further, he knows they’re stupid. One has the sense that it is their lack of intelligence in the abuse of power for which he cannot forgive them.

In any case, Breslin sold the novel to the movies and made enough money to give up being a newspaper columnist—so the mayoralty election year turned out to be a good year for him, if not quite so good as it was for Mailer who won both the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize and went on to write about the moon. All of which makes one doubt the sense of Joe Flaherty’s statement contrasting Mailer with the “liberals”:

Advertisement

He was exposing himself to all comers; he was putting his secure literary reputation on the very fickle line of a voting booth, and since there was no way to hedge his bet, it was a gamble they couldn’t understand….

Me neither. What did Mailer have to lose but his amateur standing? To be sure, as a professional contender, Mailer lost to—among others—his own running mate, Mr. Breslin, who racked up almost twice as many votes as the head boy.

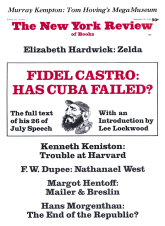

This Issue

September 24, 1970