A hundred years after his death Dickens’s reputation stands higher than ever before and he is generally recognized as the greatest creative force in English after Shakespeare. Would the pair be surprised to find themselves on this pinnacle? Tolstoy and Goethe knew what was in store for them, or what ought to be in store for them, as they knew everything else about their powerful personalities; but very likely Shakespeare and Dickens rarely reflected on their future status: they had neither the time nor the inclination, nor enough sense of their persons. In spite of the countless portraits and photographs it is not easy to see what Dickens looked like—the “countenance clear as steel” that Carlyle admired melts into unrecapturable shapes which suggest only the actor of a given moment, playing the part of author at his desk, public figure, or Christmas uncle. We can imagine Shakespeare acting on the stage as we can imagine Dickens acting off it, but Dickens as Dickens is no more credible than Shakespeare as Shakespeare. Their proper existence lies in their creations, and nowhere else.

Dickens told G.H. Lewes that “every word said by his characters was distinctly heard by him.” The reader hears, too, but less what the character is saying than what he thinks he is saying. Dickens and Shakespeare are the supreme masters of giving a local habitation and a name to the airy nothing of inner eloquence. Out of the obsessional patter of consciousness they mold pyramids and colonnades of speech, which seem both the essence of the individual and his natural voice. The prose of Dickensian speech is far closer to Shakespearean poetry than Browning’s monologues are, for though Dickens venerated the author of A Blot in the ‘Scutcheon as Shakespeare’s lineal descendant, the voice that comes through Browning’s actor is always the author’s.

And yet Dickens’s greatest linguistic creations are solipsists, living in a world of their own and holding no rational exchange with their fellows. After Pecksniff and Mrs. Gamp have spoken there is nothing to reply. Angus Wilson enlarges the point in his superb—and superbly illustrated—critical biography, one of the most comprehensive studies of its kind.

The male verbal maniacs deal in abstractions, in empty rhetoric, as befits man’s education. But the women of the species pour out the folklore of their age in concrete images that form a visual mosaic. Mrs. Nickleby’s is a mosaic of the folklore of gentility, Flora Finching’s of romanticism, Mrs. Gamp’s of the lives of the poor…. The squalor, the greed and the brutality of Mrs. Gamp are woven as closely into all the tag ends of religiosity, folk wisdom, macabrerie, coy salaciousness and sickly sentiment that make up her speech, as the brutality of the lives of the Victorian poor was blended with all their desperate attempts to evade it.

That is it. Type and idiosyncrasy, reality and wish fulfillment merge as inevitably in these speeches as they do in life. And though the rhetoric of the Elizabethan drama flourishes, communication has broken down. When it is necessary that one man should understand and act on what another is saying the pressure of creation falls off, or is kept up only when the barriers of class retain each speaker in his own world, the different worlds of Pip and Joe Gargery, or of Mrs. Gowan and the Meagleses.

Dickens had an unerring eye for the way in which such distinctions are consciously or unconsciously maintained in speech styles—G.K. Chesterton observed that those who said Dickens couldn’t describe a gentleman really meant that he described them as gentlemen don’t like to be described—but it follows, to use E.M. Forster’s distinction, that his greatest characters are his flattest ones. Flat—as the Marxist T.A. Jackson pointed out, and his judgment is emphasized by Barbara Hardy in her centenary study—because that is how their roles, their greeds, their professions have made them. Dickens understood perfectly the professional state of men—part automata, part creatures of kind, like Wemmick in Great Expectations: and the intolerableness of figures like Little Dorrit is their lack of this naturally grooved and channeled personality, for when Dickens worshipped he closed his eyes. Nor did his eyes avail him with a foreigner: his Frenchmen and Americans fail not because they are flat but because their characteristics are wholly typical, never unique; though Steven Marcus has maintained that Dickens here showed true perception, for in emergent American democracy manners were standardized, with no room left for the inner oddity of the self.

Dickens at his best has always inhibited the critic. “I have been talking not about Dickens,” confessed Chesterton, “but about the absence of Dickens. What is there to be said about earthquake and the dawn?” Since Henry James’s review of Our Mutual Friend it is indeed Dickens’s absences that have attracted most critical attention, and have sometimes been converted into virtues, as with Dr. Leavis’s strangely perverse adulation of the propaganda in Hard Times. Modern criticism has sought to turn the “earthquake and the dawn” into a jargon more acceptable to intellectual taste: hence the emphasis on symbolism, “organic poetry,” and “episodic intensification,” which dark phrase seems to mean no more than that some chapters and scenes in the novels are markedly better than others.

Advertisement

The intellectuals turned to Dickens, as to Shakespeare, late in the day; but having turned they created a version of him in their own image. And whatever its illuminations, such criticism must be ultimately misleading, for it erects a structure that puts Dickens with novelists whose relation to their readers is not that of Dickens to his. He needs his readers immediately and imperatively—“make ’em laugh, make ’em cry, make ’em wait”—and his readers’ response to his novels shaped their progress and direction: we are still under the necessity of responding or failing to respond to a performance, not judging from outside a work planned and executed without our cooperation. Oscar Wilde said one must have a heart of stone not to laugh at the death of Little Nell, and indeed laughter and tears are not really alternatives but virtually identical, twin modes of socializing the solitude of pathos. In a useful collection of essays on Dickens the Craftsman, J.R. Kincaid analyzes the structure of The Old Curiosity Shop to show how Quilp and Nell, aggression and passivity, are interchangeable modes of response in the melodrama. Long before Freud Dickens intuited our need to identify with both kinds of behavior.

Himself a distinguished novelist who has been much influenced by Dickens, Angus Wilson understands this aspect of things very well. His first sentence is Dickens waking from a childhood nightmare—“I know it’s coming! O! The Mask!”—a cry from the labyrinth of fear which is at the heart of his adult vision. And Angus Wilson talks of

…the discovery by the highly educated in the last thirty years that Dickens, with his extraordinary intuition, leaps the century and speaks to our fears, our violence, our trust in the absurd, more than any other Victorian writer.

The lifelong display of child and responsible adult side by side—indeed the almost over-responsible adult, for as Wilson later comments, “a sense of responsibility for others, so long as he did not feel himself threatened by them, was developed in him to an almost incredible degree”—is typical of Dickens’s transparency: he could be either one at will without the paralyzing inhibitions of introspection and self-analysis. Yet this instinctive extroversion rather than examination of private terrors and hatreds was not all gain: as Edmund Wilson detected some while ago there are parallels between the giant genius of Dickens and the dwarf genius of Kipling. Both strove to overcome the solitude of a private wound by means of a close and immediate emotional relation with their audiences. Both, too, rejected the past and all its hallowed institutions with particular virulence, as if by disowning it they could disown their own childhood miseries.

But there the comparison ends, for Dickens’s radicalism—and the heart behind it—were of a far more capacious scope and finer quality. His intense up-to-dateness, stressed continually by Angus Wilson, contrasts with all the more apparently thoughtful and analytic Victorian novelists, with the nostalgias of Thackeray, the retrospection of George Eliot, and Trollope’s comfortable shrewdness as a man of the world. In their different ways they all fitted into their society far better than Dickens did. His alienation is that of a modern man, while his powers of universalizing what he saw—the swarming streets and self-absorbed lives of London—could hardly have survived the swift escalation in the size and complexity of our society. In his last novel the social scene has shrunk, as Angus Wilson comments, “almost to the professional classes of one cathedral town.” Dickens’s genius was extraordinarily adaptable, and there could well have been a compensating gain in concentration and form, but Edwin Drood would surely have been a withdrawn novel—a mystery as its title tells us—in which the close participation of the audience would not have been solicited, nor even invited.

One of the main theses of Raymond Williams in his short study, The English Novel from Dickens to Lawrence, is to link Dickens closely, as a novelist of society, with George Eliot, Hardy, and D.H. Lawrence. All of them were able, he feels—though Lawrence only in Sons and Lovers—to encompass with authority a community which they could see and know without having to explore it from outside, a community which was a real microcosm of the nation at large. With the disappearance of this authority comes the substitution of symbolic or pseudo-societies, as in Lawrence’s Women in Love and E.M. Forster’s Howards End, over which the novelist can exercise the authority of his ideas in a simplified and increasingly subjective setting. This is an argument of prime importance, for it emphasizes Dickens’s underlying seriousness and confidence as an analyst of community and institution, who can both exhibit a local issue or situation and raise it to the level of the universal.

Advertisement

Some of his targets have not unnaturally disappeared into history. The editor of Dickens 1970, Michael Slater, contributes an illuminating essay on “Dickens’s Tracts for the Times,” which draws attention to the novelist’s dislike and ridicule of the Tory gimmick of “Young England,” ingeniously cooked up in the Forties by the party’s brilliant public relations man, Disraeli. This loaded plea for traditional Englishness was lampooned by Dickens in The Chimes.

Restore the good old times, the great old times, the Grand Old Times! Raise up the trodden worm into a man by the mysterious but certain agency (it has always been so) of stained glass windows and enormous candlesticks…. Then his regeneration is accomplished. Until then, behold him!

These manically ebullient skits were replaced in the paper Household Words by solid articles, written mostly by Dickens’s assistants with finishing touches by him, and concerned with what was actually going on in public life, in dockyards, prisons, schools, and in the new Post Office. Harry Stone has done a service for Dickensians in editing those pieces to which Dickens made only a small contribution: they show how Dickens’s own style and ideas inspired his colleagues and produced a uniformly high standard of brilliant factual journalism. Henry Morley’s Swiftian skit, “Our National Defences against Education,” gave informed and unqualified praise to Prussian schools and educational methods—praise which Dickens, who added a few paragraphs, certainly concurred in at a time when his heroworship of Carlyle extended to Carlyle’s enthusiasm for all things German, but which is oddly incompatible with his attack on formalized educational methods in Hard Times.

Such inconsistency is a sign of Dickens’s humanity, but also of his tendency to override a cool and patient approach to a problem in the name of human values. Self-taught himself, it seems likely that he unconsciously resented education, and neither grasped, nor wished to grasp, that for most people it requires the mechanism of discipline and standards. John Holloway has shown that the attack in Hard Times misunderstands and misrepresents its target, while in the essay which follows Michael Slater’s in Dickens 1970, C.P. Snow considers Dickens’s long battle with the monster of the “Establishment,” the rottenness of incompetence, snobbery, and self-interest which were allegedly eating out the heart of England. “Dickens and the Public Service” shows with scholarly lucidity how Dickens was both right and wrong about the Circumlocution Office of Little Dorrit. Since the report of 1853, two years before Little Dorrit, the civil service entry had been by open examination, and even before that it had never been the aristocratic preserve of Tite Barnacles but of ambitious and usually conscientious middle-class families.

Dickens, as he well knew, was claiming a contemporary significance for a novel set thirty years back. Yet he could not have been more right in the main perception: that all government offices at all times are run in the same kind of way. What set “the tom-tom of his rhetoric beating,” as C.P. Snow says, were “the nightmare oppressions of all administrative systems everywhere”; and it beats for us today not less but more loudly, for every highly organized nation is now controlled by its Circumlocution Offices. Snow points out that the critics Jack Lindsay and Edgar Johnson were in error in pronouncing this aspect of the novel an exposure of evil in the capitalist system, and he accurately compares the travails of the unfortunate Mr. Doyce in Little Dorrit with those of the hero of Dudintsev’s Not by Bread Alone, published in the Soviet Union in the 1950s.

Snow also reminds us that by an irony the real Circumlocution Office had wider power and more influence than even Dickens had foreseen. A highly critical piece on Little Dorrit was written for the Edinburgh Review by James Stephen, the son of Sir James, who was one of the ablest civil servants the century produced in Whitehall. Its accusation of “hasty generalizations and false conclusions” was in some degree justified, and Dickens’s laboriously sarcastic reply in Household Words was not a convincing rebuttal. But the point of future interest was that the reviewer’s brother, Leslie Stephen, and his daughter, Virginia Woolf, exercised great influence in the literary establishment after Dickens’s death, and undoubtedly helped to form the widespread opinion among the intelligentsia that he was not really a serious author. So Tite Barnacle, whom the Stephens held to be a parody of their distinguished progenitor, triumphed for a space: not as the aristocrat Dickens had portrayed, but through the medium of the cultural haute bourgeoisie which subsequently became Bloomsbury.

Both in her short study of his novels and in her essay in Dickens 1970, Professor Barbara Hardy is refreshingly brisk about the tendency to see too coherent an artistic progression in the sequence of Dickens’s novels, sophisticating the pattern and deepening the meaning. Dickens had always been well aware of the medium he worked with—the memorable asides in Oliver Twist on how the novelist presents reality show us that—but there is no evidence that aesthetic revelations came to him by reflection and theorizing as they came to Henry James. As Professor Hardy puts it:

How easy it would be to talk about the complex psychology of late Dickens heroes and heroines, did not Edith Dombey show the same self-division as Louisa Gradgrind, did Lizzie Hexam not show an identity very like Nell’s, did Pip’s complexity not prove, on close inspection, to rely very largely on narration rather than drama.

This is a salutary point to remember, as studies multiply from critics who are more at home with what Virginia Woolf called novels for adults. In fact a relish for Dickens, as for detective stories, is usually only acquired in maturity—children find him too upsetting and adolescents too simple-minded—and it may be significant that his main change in technique was in response to the fashion of the detective mystery. The transformations in Shakespeare’s dramatic modes were no doubt also brought about by external rather than internal considerations.

A.E. Dyson’s The Inimitable Dickens contains some of the best studies of individual novels since Steven Marcus’s Dickens from Pickwick to Dombey and is full of comparable insights. His comments on the blast furnaceman who befriends Little Nell, or on Dombey’s Freudian slip in his epitaph for Paul (“Beloved and Only Child”) have as their premise the essential sleepwalker in Dickens, the man who could achieve prodigies of psychological delicacy and intensity without seeming to know or care, the man whose waking self would gloss them with some trite rhapsody in keeping with their spirit but totally removed from their actuality, the seer who profited so enormously from not seeing what went on in his own mind.

In the essay on David Copperfield Dyson discusses Dickens’s division between love and sex. The child needs and longs for love, indeed stands for it: sex bewilders and divides him. Sex for Dickens is an aspect of the demonic will that drives so many of his characters and that drove himself. It is an unseen dynamo, but the energy it generates must appear in other forms. If Quilp were explicitly a sexual monster—unthinkable, it is true, in such a publication at such a time—it would mean the collapse of that visionary span which unites his exuberant violence to Nell’s passive innocence. If Dr. Strong was sexually a non-starter then it is counted to him for grace, and his wife’s exoneration from the rumor of infidelity follows with a kind of logic from the truth that “there can be no disparity in marriage like unsuitability of mind and purpose.”

Where love is, sexual compatibility is an irrelevance, as Dickens may possibly have inferred from the case of the Carlyles. Dickens’s own marriage foundered on “unsuitability of mind and purpose,” and he seems to have regarded its sexual side as something for which he was not responsible, and which Kate managed as incompetently as everything else in the household (“My wife is again in an interesting condition—not interesting to me alas”). Mary, her younger sister, whom he had worshipped in the early days of his marriage, and Georgiana, who ran his house so well in later years, were loved all the more because sex was not in question: they could be for him “all that woman might be for man.”

The separation of desire from love and order, kindness and decency, does seem a given fact of the Dickens world, and one that went both with the spirit of the age and the importuning of his own imagination. In her essay in Dickens 1970 on “The Sexual Life in Dickens’s Novels” Pamela Hansford Johnson implies a comparison between the tenderness of the bizarre child marriage of Dick Swiveller and the Marchioness in The Old Curiosity Shop and the exasperation, disillusion, and gloomy complicity of the newly married Lammles pacing the beach in Our Mutual Friend.

So effectively suggestive is this scene that the Lammles’s discovery that they have been deceived about each other’s money gives the strong impression that they have also been deceived about each other’s bodies. The dialogue and situation of the Lammles are Trollopian, but their undertones are pure Dickens. The Lammles are grown-up, ruthless, commonplace, soured; hence potentially sexual beings, for the scene is so markedly lacking in all Dickensian elements of the bizarre, the pathetic, the outrageous and grotesque that we feel where these things are not, there sex, almost by default, can be.

Critics have often remarked on the degree of sexual realism in the last novels—Angus Wilson even queries the nature of the relation between John Jasper and Edwin Drood—and they usually attribute it to Dickens’s association with Ellen Ternan. Here at last was the child-wife with whom it was possible—even in a sense obligatory—to go to bed, but there seems no doubt that the consummation of his lifelong fantasy filled Dickens not so much with guilt as with disillusion and despair. Ideally he would probably have liked yet another romantic attachment, which, though it could not now be like that of David Copperfield for Miss Larkins, might have resembled Pip’s for Estella. Though she caused Pip exquisite misery, of which he is conscious every second that he spends with her (a touch straight from Dickens’s contemporary experience), he has no lust to possess her, and in the original version of the novel’s ending no prospect of doing so.

Pamela Hansford Johnson’s trenchant comments will no doubt soon be taken up in more earnest and exhaustive style—some researcher’s Dickens and Sex joining Philip Collins’s learned works on Dickens and Education and Dickens and Crime. In the last few years criticism on Dickens has multiplied greatly and no doubt there is much more to come. But Dickens’s works, like Shakespeare’s, can support a whole critical industry and remain unaffected by it. Novelists as different from each other as Proust and George Eliot, Henry James and D.H. Lawrence, have become almost coexistent with the best commentaries on them, which can think or rethink their thoughts, use their terminology, and inhabit the same style and the same world. Not so Dickens. Once in his world we forget that anything has ever been said or written about him, or could ever need to be.

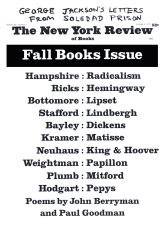

This Issue

October 8, 1970