This book is news. Time magazine says so. Its publication was announced in the August 17, 1970, issue not back in the “Books” section along with conventional literary events, but right up front in “The Nation,” with a full-page spread including a big picture of Martin Luther King, Jr., leaving J. Edgar Hoover’s office after their famous 1964 meeting. Curious about Time’s generous attention to the book, I was assured by one of their senior editors that the story is not part of any policy decision to vilify King: “It was probably published because Williams represented a hard look at King by a black man, and his debunking was interesting from a journalistic viewpoint.” The writer of the Time story agrees that there is probably no new information about King in the book, “but Williams’s evaluation that King was a tool of white power is new.” I did not press this point.

Williams’s “message,” according to Time, is that King fatally compromised the struggle for black liberation, that he permitted himself to become an instrument of white strategy, that he was incorrigibly afflicted with the hubris of the black bourgeoisie, and that he was intimidated by the FBI’s knowledge of his “extensive and vigorous sexual activities.” The last item is particularly savored wherever rightthinking Americans gather. At the Rotary Club of Algonquin, Illinois, and the Citizen’s Council of Birmingham, Alabama, the “word” about King’s sex life produces smug smiles of vindication. That King was a Jew-loving commie, clerical charlatan, and the most notorious liar in America, these things were beyond argument; but that he was a lecher and an adulterer, who would have thought it?

We need critical studies of Martin King, not simply to demythologize him, to reduce him to the more pedestrian humanity with which most of us are comfortable, but to understand him as central to a revelatory historical moment in American life. Coretta King’s My Life with Martin Luther King (Holt-Rinehart) is an invaluable memoir, but it is far from the analysis I have in mind. Lerone Bennett’s What Manner of Man (Johnson) is an excellent popular treatment, which I hope will be revised (for the fourth time) soon. Martin Luther King: His Life, Martyrdom, and Meaning for the World (Weybright & Talley) by William Robert Miller is flawed by its excessive reverence, but is, nonetheless, the most thorough treatment so far of King’s intellectual and religious development, a side of King that is frequently neglected.

The best study to date is David Lewis’s King: A Critical Biography (Praeger). Lewis, a young black historian, did a prodigious amount of research and produced, within the year following King’s death, a carefully reasoned study of King and his movement. Though he began with strong reservations about King, both as a man and as a political activist, Lewis was compelled to conclude that King’s person was more remarkable than the myth surrounding him, that, at the time of his death, he was on the way to building a movement of “internationalist populism” that overshadowed in its promise all his prior achievements.

John Williams’s The King God Didn’t Save is something else. Querulous, unorganized, wrong on factual matters of both a major and a minor kind, self-contradictory to the point of incoherence, it has passages of powerful prose and moments of plausible anger, but it finally subtracts from the sum of our knowledge about King. With a few small reservations, it may be said of The King God Didn’t Save that what is new is not true and what is true is not new.

John A. Williams is a writer of some distinction (This is My Country Too, The Man Who Cried I Am) and a black man who alternates between being a literary exile and an American social critic. Between 1956 and 1968, Williams commuted between Europe and his Manhattan (Chelsea) apartment. Often, as he says, he was “watching from 1700 miles away.” The subtitle, “Reflections on the Life and Death of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” suggests the book he might have written, personal and impressionistic, and enhanced by the insight sometimes manifest only from a distance. Instead, Williams offers us a pastiche of old newspaper clippings, discarded memos, lengthy quotations from his other books, and random conversations with a few people who knew King: all of these glued together with the subterranean gossip and rumors which commonly attach to famous persons. An exposé of King’s private life may have some conceivable purpose, but Williams obscures more than he exposes, and what he does reveal (contrary to the promotion in Time and elsewhere) will surely disappoint readers with an appetite for the salacious.

Readers who share Mr. Williams’s antipathy to King may contend that his numerous misstatements of fact do not invalidate the essential thesis, and perhaps they are right. Carelessness about particulars does, however, tend to weaken the force of argument. A few examples are in order: Williams claims that King was “beating the hustings” for LBJ in the 1964 election at a time when King was recuperating in an Atlanta hospital and, later, preparing to receive the Nobel Prize. John Kennedy, Williams writes, co-opted the 1963 March on Washington and “ironically linked the aspirations of the march…to labor and Labor Day”; when, in fact, an increased minimum wage was among the March’s central demands. Williams attributed singular blame to King for the insistence that SNCC’s John Lewis tone down his speech at the Lincoln Memorial; in fact, King was in Atlanta when that discussion took place and SCLC was represented in Washington by Walter Fauntroy, who agreed with the unanimous decision of the leadership that there should be no direct personal attack on Kennedy, which is what Lewis intended to deliver.

Advertisement

Williams describes the Kingsponsored Union to End Slums as “painting and refurbishing” the Chicago apartment before “the big wheel” and his family moved in for the Chicago campaign; in fact, the apartment was hastily repainted by the slumlord, much to the embarrassment of King and UES. Williams suggests that Bayard Rustin was influential in pushing King toward more radical opposition to the Vietnam war; in fact, Rustin, who supported both Johnson and Humphrey, and later broke with SCLC on the Poor Peoples’ March, was clearly one of the more conservative forces in King’s work. (Although Williams is bitterly critical of almost everyone involved with King, he is strangely sparing of Rustin. It is from Rustin that Williams gains corroboration for his judgment that King was too middle-class and out of touch with grass-roots black people. The humor of this will not escape those familiar with Bayard Rustin’s career.)

Williams sees a white conspiracy in the “poor reporting” and “soft pedaling” with which the press received King’s April 4, 1967, Riverside Church speech on Vietnam; in fact, that statement was probably given more exposure than any other speech of King’s since the “I have a dream” speech of 1963. Williams says that the Roman Catholic hierarchy desperately opposed King’s proposal for a guaranteed annual income because it “flew in the face of a church tradition, the corporate gathering of wealth.” The sins of the bishops are many and odious, but the social action arm of the US Bishops’ Conference has been on record in favor of guaranteed income proposals at least since the early days of the New Deal. And so the errors accumulate.

Williams is a hard man to satisfy. At one point we are told, “The record revealed that during every demonstration in which King participated, at the key moment when he was most acutely needed to lead a mass confrontation, he was absent.” Then, a little later, “He went to jail in St. Augustine, of course, for that was the pattern; he and Abernathy always went to jail—but on their own hook, away from the hymn-singing demonstrators, almost never caught up in the mobs.” If King gets arrested early, he is aloof from the mobs; if he gets arrested late, he misses the confrontation. King can’t do anything right.

According to Time, Williams “interviewed many of King’s friends and associates in preparing his book.” Williams himself, wisely, makes no such claim. Of the people he does cite, Rustin and Harold DeWolf, King’s theological mentor, might be described as “friends and associates.” (Rustin, as I’ve suggested earlier, had at best an ambivalent relationship to King, especially toward the end, and Williams dismisses DeWolf as “more a businessman than a theologian,” whose testimony is tainted by a racist double standard.) Other major witnesses are James Meredith (whom Williams considers “spooky” and severely disturbed) and Ella Baker, a woman embittered by her removal from SCLC leadership whom David Lewis describes as believing that “Martin was a phantom of the news media, a symbol without more substance than that of hundreds of other Southern Baptist preachers” (quoted by Lewis, p. 213).

Williams apparently tried to interview others, but too often their statements were inconvenient to his argument. For example, he cites “a young man connected with SCLC” who said in 1963 that there was a move under way to replace King as SCLC president. Others were not so critical, writes Williams, “but then nearly all of them had grown up with King.” The reader is given the impression that King surrounded himself with sycophants. Williams concedes that there were also stronger personalities, but “even those who were bright and strong became real followers.” Naturally there are witnesses to King’s modesty, fearful sense of duty, and self-sacrificing devotion, but their opinions must be discounted since what they say only reveals the seductiveness of King’s egoism.

Advertisement

Time says Williams is a man gripped by “seething black anger” who has something to say. And Saturday Review (August 22) says this is a “most intelligent” book. In the light of these recommendations, one should of course keep an open mind. But Williams finally overpowers the reader’s best effort to take him seriously. For example, he advocates revolutionary violence, on the one hand, and affirms the vote as the black man’s most powerful weapon, on the other. He tells us that King died before his time; just as he was entering upon his most creative work, while at another point Williams agrees that “King’s killing was the best-timed one [for black people] in this century…. He was on his last legs.” We read that King “did not understand that it [white power] had armed him with feather dusters…. He was a black man and therefore always was and always would be naked of power, for he was slow, indeed unable, to perceive the manipulation of white power, and in the end white power killed him.” Good, we think, we have grasped Williams’s argument, until we are confronted with the statement that King was as threatening to white power as Malcom X and that both had to die because “they attempted to mount programs involving not only blacks, but the oppressed of every race and kind.” Indeed one could say that The King God Didn’t Save is refreshingly free from that excessive ideological consistency that mars so much radical literature, especially the kind that is characterized by “seething anger.”

Mr. Williams’s message is consistent on some points, however, notably in its hostility to non-violence and to religion, especially Jewish religion. Because of the infernal combination of religion and non-violence, writes Williams, “Martin King really, really got under my skin.” It seems Williams’s eldest son, inspired by King’s example, wanted to become a minister. But as he grew up his religious interests declined, Williams writes, and “non-violence slid away from him and I watched with relief. He had to discover things for himself, with some aid from me.”

Williams has strong feelings about religion in America. “In the United States there are three major and politically, not to mention economically, powerful religious groups. They are the Protestants, the Catholics and the Jews.” Martin King, he says, had to battle all three but, since he was “naive as hell,” never did recognize that the churches would always reject his call because “most people who consider themselves Christians were, in fact, something far different from the ideal Christians he envisioned.” “Western civilization is based more on money than on morality,” he writes, and people do not practice what they preach. From these hard truths, he moves to a brief excursus revealing the villainy of Roman Catholicism (the Spanish conquistadors, devout Catholics all, introduced slavery to this continent), and at last reaches the most insidious of religious conspiracies, the Jews and their money.

“No sooner did King appear on the verge of becoming a national figure than a couple of Jews were at him, one on each ear,” Williams is told by “Person A.” He notes that Person A is Jewish and told him this “with humorous pride, saying, in so many words, that a Jew knows a good thing when he sees it.” Stanley Levison, for example, a lawyer who early became one of King’s chief “fund-procurers,” and Morris Abram, later head of Brandeis, were among those, Williams was told, who “pretended to be working for civil rights, when in reality they worked for the establishment.”

Jewish leadership created “the illusion that all Jews were in accord in feeling a sense of closeness to Negroes [but] the fact of the matter is that Jewish interest in black problems is comparatively recent.” Not only recent, but ephemeral, for, when black interests no longer “coincided temporarily with the interests of the Jew” the alliance was called off. King would realize too late that he was caught in the Jewish money trap. Jewish money moved away from CORE, SNCC, and other more “realistic” groups, and toward SCLC. “Martin Luther King would respond to this aid.” He “responded,” for example, by giving a speech, sponsored by the American Jewish Conference, on behalf of Soviet Jewry. Later King was to “respond” again when Jewish leadership requested that he refute the position on Israel taken by the black caucus at the 1967 Chicago New Politics Convention. “That request was not unlike a demand.” In sum, “Jewish leaders utilized King as the ‘house Negro’ to refute the allegations of other more militant Negroes.”

On black anti-Semitism: “The Jews first attacked the blacks [and] now that it was in the open, Jews took off in full cry, howling down any display of black anti-Semitism.” It was widely reported, for example, that at a meeting in Westchester a local CORE leader shouted that Hitler had been right to do what he did to the Jews. “But the other side of the account got little circulation. It seems that the black man was angrily responding to a racial insult by a Jew.” By all means let us hear all sides, but is there “another side” to the outrage one feels at hearing praise for the Holocaust? As someone who has been arrested several times in actions opposing the United Federation of Teachers, I know well its shameless exploitation of the charge of black anti-Semitism in its fight against community control of New York’s schools. One should be exceedingly cautious in attributing anti-Semitism to anyone, but Williams’s undiscriminating indictment of Jewish support for the black struggle seems to be inviting the charge.

At the conclusion of Williams’s polemic against American religion, which consumes about 20 percent of the book, he notes, “Martin Luther King was not an ignorant man. He must have known to some degree all that I’ve set down here and more.” Perhaps, Mr. Williams, at least to some small degree.

From the theological to the scatological is not very far. Williams is discussing the government’s suspicion that King had communist affiliations. Then, as though from nowhere, this is inserted:

“I knew Martin Luther King as a man.” “Yes,” I said, “but what does that mean?” She was extremely fair and had freckles. Her answer was a giggle.

—Person D

A few pages later, we are told about King’s preoccupation with his standing in the popularity polls, when, abruptly, we are faced with another surprise:

“There were two pictures. One showed me sitting on the floor beside the bathtub in which Martin sat, naked. From the angle of the photo, it looks as though I was doing something. The other photo showed me sitting on the bed beside Martin, who’s laying there, nude. Now, in both cases, I was conferring with Martin in the only time available to me. Nothing, absolutely nothing took place.”

—Person C

And finally:

“Martin and the rest of them had a code. A very attractive woman was called ‘Doctor.’ I forget the other names for women not so attractive.” “What were you called?” “I was a ‘Doctor.’ ”

—Person B

That is the extent of Williams’s information about what Time calls “King’s extensive and vigorous sexual activities.” One infers from the way he uses this material that Williams spoke with Persons B, C, and D. But he tells absolutely nothing about them, indeed there is nothing in the text to explain the above quotations. Were these women associates of Dr. King? call girls? or mixed-up souls looking desperately for some connection with fame? Should we credit their testimony? Does Williams? Or is his use of it simply a literary device to illustrate the type of rumor circulating about King? The last seems possible, just as Williams elsewhere embarks upon a lengthy psychological analysis of King (sample: “Black became beautiful, although his secret distaste for black women remained constant…. This was the makeup of the small pudgy man who was Martin Luther King”) while admitting he never knew King and did not research his subject with those who did. It is all very confusing. The only certainty is that the book will frustrate those readers who were led to expect the inside story on King’s private life.

But what difference does it all make? So what if Time used Williams’s book as an occasion to charge King with extensive extramarital affairs? Some, black and white, will consider the charge more compliment than crime. Others will insist that the private life of King has no bearing on his public achievement. However, whether or not the practice of adultery is a virtue, making the distinction between private and public life, while useful, has severe limitations, especially in the case of Martin King.

King and the cause he represented, and to a large degree still represents, had wide moral appeal. For millions of Americans in Algonquin, Birmingham, Saginaw, and in New York City, morality definitely includes sexual morality, and sexual morality drawn along rather conventional lines. Because the person of Martin King and the purpose of the movement are so inextricably connected in the minds of many people, the allegations in Time must concern everyone who cares about changing attitudes on racial justice in America.

Williams relates how FBI agents approached various newsmen and offered them titillating details about King which were supposedly contained on tapes from the wiretap of King’s phones.* As these rumors gained currency, some newsmen, says Williams (and this seems likely), were cooler to King and his programs. David Lewis painstakingly traced the gossip and reports (King, p. 258):

If there is a scintilla of truth to these rumors—and they remain no more than that—it is curious that, after an exhaustive sounding of nonattributable sources, there is perhaps only one figure, a conservative U.S. Senator, who claims to have read an incriminating transcript of these tapes. Together with the Kennedy autopsy photographs and the history of Tonkin Gulf, the content of the King tapes remains a closely guarded secret.

Time makes a further claim, which, if true, supplies a disturbing answer to the question whether the allegations make any difference: “[At their 1964 meeting] Hoover, Time learned, explained to King just what damaging detail he had on the tapes and lectured him that his morals should be those befitting a Nobel prizewinner.” Hoover told King to cool it or else, and “King took the advice.”

Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, and Walter Fauntroy issued a joint statement in response to the account in Time, labeling it “totally false.” “All three of us were present during the entire discussion and at no point did Mr. Hoover lecture Dr. King or even comment on his personal life.” Whom to believe? Was King the victim of a shakedown by Hoover’s school for scandal, or has Time sacrificed fact for journalistic sensation?

I confess to being intimidated by the formidable statement, “Time learned.” It conjures up the image of the Luce empire with its legions of snoops and editors, investigating and sifting evidence until, finally, with an authority approaching that of Holy Writ, Time bestows its findings upon its millions of trustingly expectant readers. I was therefore somewhat taken aback to discover that the Time story was written by a personable fellow who usually worked in the “Medicine” section but had “just happened to read the Williams book the week before and thought it might make a good story.” He mentioned it to a friend in “The Nation” section who told him to go ahead and write it, so he did. It sounds very much like the way we put together our parish newsletter, weekly circulation 1,500.

I spoke to the writer:

Me: Who are the “many of King’s friends and associates” you claim Williams interviewed for his book?

Time: Well, he talked to a lot of people at rallies King led, like the 1963 March.

Me: Where does Williams say that King “accepted the Nobel Prize as if it were an inalienable right rather than a cherished award,” which is what you say he said?

Time: Well, he may not actually have said that, but it’s the impression I got from the book.

Me: [Now we get to the delicate part.] From whom did you learn what happened in the meeting with Hoover?

Time: From a usually reliable source in Washington who has been dependable in the past.

The writer did not get in touch with Abernathy, Young, or Fauntroy who—and this would seem of some importance—were at the meeting. He believes his Washington source has heard the tapes but does not know whether he was present at the meeting. The alternatives seem unavoidably limited: either Time’s source was at the meeting and, since he was not part of Martin King’s group, is a colleague of Mr. Hoover’s, or the source was not at the meeting and Time has only hearsay about what happened there. Being neither a lawyer nor a journalist, I can think of no other possibilities. Considering the several witnesses, and exercising simple logic, I conclude that Time is telling lies.

There remain unanswered questions. For example, why did Williams launch his diatribe against Martin King? Perhaps he did it because he is bitter about being rebuffed in his offer to help in organizing the 1963 March. “The point here is that one must be something of a ‘club member,’ with the right kind of views, background, and aspiration, to become a member of any group…. It isn’t much fun to spend July or August in New York City, in any case, and I was rather glad my obligation to the ’cause’ had been shunted aside. I hastily headed for East Hampton to lie in the grass and swim, planning, however, to attend the march.” Or perhaps attacking Martin Luther King for being middle-class is an easy way for middle-class Negroes to acquire black credentials. I suppose the credentials are accepted, at least among Negroes traveling on similarly fraudulent papers. Perhaps Mr. Williams just wanted to make a few dollars with a book that could be put together quickly and with a minimum of effort. Or, and I am open to this, perhaps Mr. Williams believes he has a message and is possessed by the urgent need to deliver it.

What I find especially hard to forgive, however (though to be unforgiving is no virtue in a minister of the gospel), is Mr. Williams’s claim that he is deeply angry at the way rumors were used to smear Martin King. He suggests there are infinitely more interesting tales about John Kennedy, but Kennedy was not handicapped by them because he was a white man. Yet who puts the very scandal he deplores between hard covers and peddles gossip as fact, if not John Williams? Williams’s self-righteous indignation at “white power’s conspiracy to plug the memory of King with putty” is pathetically unconvincing. The pious pornographer who deplores what he pushes is a familiar figure. The King God Didn’t Save is something new, pious porno with a racist twist.

People close to King expected that the whispers would someday, by somebody, be worked into a big story, maybe with a two-page spread in The National Enquirer. But last year the Enquirer moved away from sexationalism and hatchet murders in an effort to go respectable. It was left to Time to occupy the journalistic territory that had been vacated.

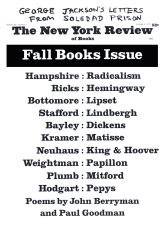

This Issue

October 8, 1970

-

*

In The New York Times Book Review (August 30), James McPherson of Princeton writes, “Williams talked with newsmen who claimed to have heard the tapes.” This is inaccurate, although Williams does quote a newsman who says he has heard of newsmen who claim to have heard the tapes. The Time magazine writer discussed above says he knows of no newsman who claims to have heard them, although jokes and innuendoes about what is supposedly on the tapes are common in some newsrooms around the country.

↩