The last volume of Bertrand Russell’s autobiography received little attention when it appeared, not long before his death. Yet it raises a number of questions and doubts which are relevant to the thinking of radicals and liberals in the United States and in Western Europe today.

Covering the years 1944-1969, this third volume was principally a record of Russell’s various crusades on behalf of nuclear disarmament and civil liberties, and of his embittered opposition to American imperialism. His platform appearances on behalf of nuclear disarmament, the battles in committees, and the founding of his Peace Foundation sometimes make for dull reading now, even though they are the heroic expression of an unquiet old age. The quoted correspondence clearly shows that in this last, wholly political phase of his various life, Russell was driven forward, not only by his sympathy with suffering, but also, and increasingly, by anger: more than anger, by a generalized and philosophical rage about the human condition, and by a kind of Shakespearean disgust.

His rage was directed against the unvarying wickedness of governments and of their scientific, commercial, and bureaucratic accomplices, and, to a lesser degree, also against the docility and gullibility of a decent and deceived public. Starvation, tyranny, and wars could even now be avoided, if governments were less wickedly intent upon magnifying their own powers, and if their subjects would attend to simple arguments. If these conditions are not fulfilled, mankind will destroy itself, and will continue to suffer even worse disasters on the road to a final destruction soon to become unavoidable. These were Russell’s final beliefs, which took the place of the confident, even gay, radicalism of his middle years.

This despairing attitude of the aged Russell is one paradigm of the intellectual radical in politics: only the energy and intellectual authority were unique. Particularly exemplary are the righteous anger and the accompanying conviction that those who have power, the government and the establishment, are peculiarly corrupt in virtue of having this power; the governed, cozened and bemused, may still be open to rational persuasion from the radicals’ platforms, because they are not committed to destructive policies by purely selfish interests.

From the standpoint of this kind of intellectual radicalism, there is a natural division between the victims and their deceivers, and the shepherds always prey upon the flock, whether they be capitalist entrepreneurs and managers or commissars and party hacks. In fact the secretaries of defense and chiefs of staff of the superpowers, who are nominally enemies, are more and more united in a preconscious conspiracy to sustain their deadly international game of competitive armament and subsidized guerrilla warfare. They suppress in their own territories any radical criticism of the assumptions that justify this game, and thereby justify their personal preeminence and the exercise of their skills. They will have a common interest in suppressing dissent, student protest, the potentially subversive freedom of writers and artists, and the demands of minorities for equal treatment.

This Russellian form of radicalism makes a very simple theory of contemporary politics; but it cannot be dismissed, as it usually is, on that ground alone, for it is certainly no vice in a theory that it is simple in relation to the complexity of the phenomena which it must explain. The first question is whether this very simple theory has yielded predictions that are more in accord with later experience than the predictions based upon rival theories.

Hardheaded liberals, who have for so long derided the simple-minded radicalism that Russell represented, would surely do well to be modest and cautious at this point. For the test is: Did their alternative theories yield predictions (say in 1965 and the two following years) which were more closely confirmed by events? Did they predict that the American government, continuously advised by university professors, would persist for several years in methods of warfare and of pacification that are criminal in international law and custom, and that are modeled on communist methods? Did they predict that the American government, in pursuit of its presumed strategic interests, would prop up, by firepower and money, any puppet, however repressive, provided only that he would not have dealings with Russia and China? Did they anticipate that the principles of the Nuremberg trials and pledges to international order would be brought into contempt so soon and by a democracy? Or did they rather predict that the phrase “American imperialism” would turn out to be a ridiculous misnomer? That the allegations of war crimes at the Stockholm Tribunals would be proved a farce, providing material only for cranks?

Having participated in, or observed, debates between radicals and liberals from 1963 onward, as an alien in the US, I have a clear memory of the correct answers to these questions. The liberal theory always was that the Vietnam war was, at the worst, a mistake, a temporary aberration and miscalculation, rather like the Suez expedition of the British; the American government was not interested in strategic bases or a prolonged presence, and would withdraw if it became clear that a sustainable democratic government, with adequate local support, was not to be found; this is what I was told by the well informed. Only the radicals predicted, in 1965 and 1966, the cost-efficiency ruthlessness, now called “Vietnamization,” the imitation of communist methods in the establishment of bases, the burning of villages, the gradual extension of the war to the whole area. I remember this balance of the argument surrounding the rhetorical phrase “American imperialism,” because in 1965 I believed in the liberal theory of the war as a mistake: the theory that the Kennedy and Johnson administrations had walked into a trap, misled by their military staffs, and that, once they realized this, they would change both their policy and their military advisers.

Advertisement

But I gradually realized that the notion of mistake was soon playing the same role in the interpretation of American policy as that played by epicycles in Ptolemaic astronomy: as more and more “mistakes” accumulated the theory became untenable. The radicals of 1965 had been proved right. For liberals the prolonged aerial terrorism, the ever new burnt villages, the resettlement camps, the free-fire zones, and the Harvard professors calmly assessing their efficiency were a surprise, and seemed an inexplicable collapse in national decency. The radicals with whom I had argued, and who had not thought Russell, with his talk of “American imperialism,” a mere crank, nor the Stockholm Tribunal a farce, could, and did, say—“I told you so: why would you not believe that the American government, with its academic and military advisers, is ready to match atrocity with atrocity indefinitely in defense of American influence in Asian countries, no matter what the cost to the local populations?”

There is an answer to this question, and the radical versus liberal argument is certainly not closed at this point. The word “imperialism,” brandished by radicals and by Russell, has no more explanatory and predictive power than the theory of modern politics from which it originally derived its sense: the Marxist-Leninist theory, which yields predictions that have been discredited by events over and over again, more amply even than liberal theory. As used by Russellian radicals, the word “imperialism” serves only to summarize the facts and not to explain or interpret them, even in a minimal sense.

We have no tolerably precise and unrefuted theory of imperialism which points to the forces that now ensure that liberal expectations should be disappointed, and liberal principles trampled on, by successive US governments. Russell’s own explanations, which impute the organized brutalities to the egoism and stupidity of politicians and generals, depend upon ignoring the fact that the politicians and generals can count upon support for these policies from a clear majority of the voters. Chauvinism and xenophobia are likely now to be the majority attitude in any country, socialist or capitalist, and the liberal and radical opposition to them is likely to be a self-conscious minority. I doubt that Russell ever adjusted his theories to this fact, or that he ever gave Tocqueville’s predictions their due importance.

Unlike his predecessors and peers in public philosophy—Plato, Aristotle, Spinoza, Locke, Hume, Hegel—Russell did not apply to politics the analytical methods which he called for in the theory of knowledge. He made no solid contribution to political philosophy, although he thought continuously about politics from 1914 onward. Yet the foregoing names show that there is no historical and regular connection between being a great philosopher and also an intellectual of wide range, and ignoring, or despising, the peculiar difficulties of theoretical analysis which practical politics present. The connection was rather a peculiarity of Russell’s temperament, partly an effect of that imperious rage which he first felt in 1914 and which is so vividly described in his autobiography: and perhaps partly the effect of an austere conception of reason, derived from mathematics, which stood in the way of his ever arriving at a theory of rationality in politics, or of practical reasoning in general. He therefore contributed to the modern stereotype of the intellectual in politics as always putting a simple moral disgust in the place of a slow analysis of changing possibilities.

But the fact remains that, in this last phase, he was more truly prophetic in his emotional attitudes and beliefs than either he or his liberal critics knew. A substantial minority of a new generation, particularly, but not only, in America, now shares exactly his moral disgust, and the accompanying impatience with conventional political analysis; and this post-Russell generation has made its rage, particularly in the United States, an effective political force. But, unlike Russell, they will need, and will look for, a method of political analysis—and, in this narrow sense, a theory—which is less unreliable, under contemporary conditions, than what is handed down to them either in the classics of liberalism or by Marxists. Where will this theory be found? Perhaps a dim outline can already be seen.

Advertisement

Their first step has been critical, rather than constructive, and has earned the label—quite mistakenly, as I think—of “irrationalism.” “Reason” is a normative and not a neutral scientific term. What counts as reason, as opposed to thought of less constructive and useful kinds, is largely a matter of judgment, at least in practical and political contexts; and this judgment must refer to a sufficient, proved consistency in obtaining results in the relevant field, results which are permanently accepted as correct, and which are obtained by constant habits of thought. The academic and near-academic experts on foreign policy, who have advised the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon governments, provide an interesting counterfeit model of rationality, with all the traditional external marks of reason, without the underlying substance; this same model of rationality was paraded by Mr. McNamara and his defense advisers.

The model is not only operative in Washington, but also in universities, where strategic studies are encouraged and potential political experts are trained. It is this simulaorum of rationality in politics that students have intelligently rejected, judging it by consistency in result: and they see that unprofitable outrages and a gross political insensitiveness flow from these habits of thought, which ought not therefore to be given the honorific title of reason. The method of thought is evidently not appropriate to its material.

This established model of reason can be characterized as a coarse, quantitative, calculative Benthamism, refined by game theory, which adds and subtracts incentives and disincentives, volumes of firepower, and amounts of social services, and then arrives by computation at probable human responses distributed in a total population: which calculates the cost-effectiveness of alternative policies by the number of American lives to be lost and the amount of American wealth to be dissipated in securing the sufficient compliance of foreigners to dominant American interests. The model bears the label of rationality, not because it has proved successful in political practice, but because it has the look of a human technology and of market research and profit-loss calculations, all of which are used in the great commercial corporations; and these corporations are now the institutional models of rational planning.

Within the last few centuries, it has been conventional to contrast reason both with sentiment and with intuition, that is, with any sense of confidence that a judgment is correct which is not defended and maintained by reference to a regular method of computation. Therefore those, and particularly students, who are now expressing their disgust at computational politics are dismissed as sentimentalists trying to turn the clock back to a prerational phase, when modern technology and industry were unknown. They are political Luddites.

But their challenge to the computational model of reason in politics may be philosophically defensible; and the parallel between political decision and correct solutions in the applied sciences may be largely fallacious. The survival of the species, and of any individual nation, may now, and for the first time, depend on an altogether different method of political reasoning. The ineptitude of the Harvard professors, and of the other Presidential and military advisers, has been shown to reside precisely in the apparent cleverness and the advertised coolness of their calculations, in the contemptuous “realism” of which they boasted in arguments with radicals in 1965, 1966, and the succeeding years.

Their “realistic” calculations were a failure, at least partly because of a lack of self-consciousness; they did not realize soon enough that their habits of calculation, which had earned them success under American conditions, would earn no respect or response in the scattered populations which they were manipulating. Their recommended methods of warfare and of propaganda, which are an exportation of the planning methods of commercial corporations selling a product, produce only disloyalty and a revulsion against the civilization that finds these methods reasonable and natural. The vulgarity of mind that shows through the calculations, and in the terms in which they are expressed, defeats itself; it also seems to many students to justify a repudiation of some of the forms of life which have produced it.

It is not reasonable, after contrasting calculative reason with mere sentiment, to use methods of warfare and of persuasion that are repugnant to the normal human sentiments of the aliens affected by them. In commerce the costs of failure are quantitatively calculable and limited; and in Machiavelli’s Italian cities the costs of violence and deceit were calculable and limited also, because millions of unknown men were not simultaneously involved in every political event, nor was the risk of failure ever the risk of total destruction. Critical university students have therefore now arrived at Russell’s moral disgust, but with at least one important difference: they cannot share the illusion of his traditional, 1914-style radicalism, which attributed war policies to the interests of a ruling class or group, and which pictured the working mass of the population as deluded victims. They know that they are a minority, and they believe on good evidence that the social structure which has produced the new technology of limited warfare also has its proper expression in a nervous mass chauvinism and in widespread contempt for alien forms of life. But this belief is a mere observation of fact, and they know that they still lack any tested theory which plausibly explains these connections.

If the liberal and radical intelligentsia, which includes perhaps one-third of a university age group, knows itself to be a minority in the country as a whole; if it also knows that similar, though less numerous and powerful, liberal and radical minorities exist in other industrialized countries, capitalist and communist alike; if it also knows that it still has no sufficiently precise social theory which can be made the basis of predictions and of an organized party: what forms will its political action most naturally and reasonably take?

First, it will form a unifying consciousness of itself as a pressure group, able to disrupt spasmodically, but effectively, the smooth pseudo-rational calculations of the policy-makers. Secondly, it will represent itself to itself as a movement of resistance to prevailing standards of rationality, not only in policy planning, but in social organization generally, and particularly in universities and schools. Thirdly, it will try to engender by example forms of life and moral attitudes which invert the dominant national models, and which are not only potentially international but are also unlike those forms of life that have both supported and depended on technological success in the West. They will measure the reasonableness of their actions and attitudes by independent criteria, the criteria of a minority, which is conscious of itself as being a minority.

The amended criterion of practical reasonableness will be a denial of the computational model of reason in politics, and it will single out for support those policies which are intrinsically reasonable, relative to standard and permanent common interests and sentiments. Those who adopt such a criterion will therefore reinvent for themselves a secular version of practical reason as it was conceived by theorists of natural law, which prescribed limits to the justification of inhuman policies by reference to their desirable consequences in particular cases; and these limits are to be discerned by a reasonable reflection on the intrinsic nature and quality of the actions which the policy involves. This retrogressive step now looks revolutionary.

A minority can reasonably be self-sufficient and experimental in manners and morals if it is a voluntary association of peers performing its experiments only upon itself and expecting to change the way of life of a majority only by infection, if at all; and if it is not calculating a remote change in the balance of power at the center. One can see this strategy as an extension to public life of the idea of a moratorium, which is the mode of experience of a student at a university, who naturally sees himself as enjoying a moratorium in his development.

But it will be asked—how can this moratorium and withdrawal from the computational politics of confrontation be effective in face of the totalitarian powers? Is it not unreasonable, by any criterion, to suppose that disunited and unmobilized populations will survive? This question may first be answered in its own terms, by a computation of consequences. The superior rationality of the radicals, as it seems to me, resides in the elements which, unlike the pragmatic liberals, they include in their computations of a probable future. They will include in their sums not only the interests and armaments of the opposing decision-makers, but also the limited capacities of mind and the fixed habits of thought of these men; and they will not omit themselves, the dissident minority, from the calculations. As Russell always argued, the question at issue is whether the species can survive for a long time, with any tolerable form of life, given the capacities of mind of the probable decision-makers and the nature of contemporary and future armaments.

Suppose that the development of the means of production and of destruction accelerates in a more or less deterministic pattern, and concurrently the skills, interests, loyalties, and habits of thought appropriate to these means of production and destruction are by the ordinary mechanisms reinforced and spread in whole populations: then majority support for the computational politics of confrontation between fully mobilized populations is so far assured. The radicals’ idea of a moratorium is the belief that the only point of leverage immune to these deterministic connections is to be found in those who, being temporarily dissociated from the productive and destructive process by their own interests and circumstances as students, may choose to prolong this dissociation together with the experimental habit of thought that it permits.

The contradiction in the present system of national mobilization of resources, capitalist and communist alike, may reside in the facts, first, that a large university-trained minority is needed if technology and planning are to be continuously developed, and, second, that a sufficient minority of this minority will, during its time out, see the necessity of arresting the mobilization and of interrupting its apparent deterministic connections. If one calculates that the habits of thought and the mental capacities of communist and capitalist decision-makers, together with their armaments, provide a high risk of total destruction within a generation or two, as smaller nations join the race; and if one calculates that this is a mounting risk over many generations, it becomes rational to support the moratorium policy of dissociation and to build a continuing movement around this dissociation. This is the familiar consequentialist, or utilitarian, defense of the rationality of the moratorium, one that is conditional upon a disputable calculation. This is a version of Russell’s argument, who, faithful to Mill, was always a consequentialist: his empiricist principles in philosophy would not allow him to use “reason” in any looser, non-computational sense. He therefore never arrived at a moral philosophy which would match and inform his emotions.

There is a different argument, which is reasonable, judged by the other, looser criterion of reason. If it did not arouse prejudice, it could be called the Aristotelian sense of reason. This argument appeals to certain very general facts about standard, recurring human needs and sentiments, but it does not depend on any precise computation of remote consequences. Some policies can be dismissed as contrary to reason, in spite of the consequential advantages that they may seem to bring in particular circumstances, because their successful execution would involve too great a coarsening of the sensibilities of their agents, and for this reason would make their lives subhuman, wretched, and shameful to themselves. There is a limit, set by the innate and normal structure of human feelings and interests, to the tolerable postponement of natural impulses of gentleness or generosity or justice for the sake of a future safety or advantage. The Southeast Asian policies of the US government under three Presidents, with popular support and the advice of business managers and academic experts, have been contrary to reason in this looser sense. The chosen means are manifestly incoherent with the chosen ends.

When inhuman and brutalizing means are used in resisting communist power the outcome will be a demoralized and divided population, not only despised by others, but also despising itself. This internal demoralization is not to be counted, within the theory, as a compatible and separate consequence of the policy, but rather as an intrinsic feature of the policy itself; for the original decision was to match communist methods of guerrilla warfare and pacification with an anticommunist version, and this required the adoption by the executants of the same mentality, of the same brutality in calculation; this mentality was chosen.

This is now familiar and evident. From the standpoint of the students, the significant fact is that when the free-fire zones and bombing and resettlement policies were adopted, the protests against these policies as contrary to tolerable principles of conduct did not come principally from intellectual leaders in Washington or from the academic advisers of the President or even, at first, from an obvious majority of university professors. On the contrary, I remember many members of these groups congratulating themselves on their adult and rational computation of consequences in contrast with the childish moralizing of radical students. That a large minority of students should in consequence distrust these official habits of thought, and the standards of rationality implied, and the academic authority associated with them, does not prove that they are enemies of reason. They naturally call for a rethinking, in philosophical terms, of what constitutes reasonable judgment in politics.

Beneath the opposition between the two standards of reason there is probably a deeper difference between contemporary radicals and their older liberal critics: a difference that is not easily formulated because a less than fully conscious thought is involved. It concerns the imagined time scale against which the effects of policies are calculated. A classical liberal, like Macaulay or Arnold before him, looks at contemporary institutions and habits of thought as persisting through vicissitudes in successive generations and sees the lives of only one generation, including his own life, as a phase or incident of a long process, in which some of the past is transmitted to his decendants and some is replaced in his own time. An individual’s experience of social and political change, and his own contribution to it, has often been pictured by analogy with his more primitive experience of the continuing family into which he was born. He sees his own possible forms of life as limited on two sides, by his inheritance and by his need to transmit at least some of this inheritance to his children and to their descendants. He is a station on a permanent social way.

There are probable conditions under which this intimate sense of continuity, of one’s own activities as constituting a phase, or incident, in an extending social process may be weakened, or lost, by many converging changes: by the spread of liberal ideas themselves, which deny an older stress upon inheritance; by mobility and also social mobility; by the spread of higher education, which loosens family connections; by accelerating technology, which makes the imagined future seem wholly unlike the past; also by the new image of a final catastrophe in a future war.

It is possible to picture the span of one’s own life and family and that of one’s friends, not as phases in a continuing social process, but as properly to be judged in isolation and for their wholly intrinsic qualities. One sees one’s own life as the recurrence of a standard and permanent type, and not as a small contribution to a larger whole. This is an alternative picture, in itself neither more nor less reasonable than the picture that it may replace.

The judgment of a form of life for its intrinsic qualities, apart from its contribution to a phase of social change or of social stability, was quite normal in the West in those periods when religious belief in personal survival was usual, and when a wholly secular morality was the exception. These were the periods in which morality was conventionally based upon a doctrine of natural law which prescribed some absolute rules of conduct, valid for a recurring type of situation in a recurring form of life.

When critical intelligence has undermined the general belief in the supernatural sanctions behind an individual’s normal moral judgments, the gap is usually filled by the idea of social utility in the long run; and the appeal to natural law is then dismissed from the prevailing liberal morality; for social change ensures that circumstances are always new.

But this liberal ethics presupposes both that the future of humanity is relatively secure, and also that social progress could be definitely identified as an accompaniment of general intellectual enlightenment. These two assumptions are quite explicit in Mill, and in Russell’s earlier, more jaunty radical writings on morals and politics, before the age of anger and disappointment. But many reasonable persons cannot now make these assumptions. Therefore the signs of a rejection of the criterion of long-term social utility and social contribution are not to be counted as signs of a revolt against reason, in all its known senses: they are rather signs of a return to an earlier notion of practical reasoning, which has again become plausible because of changed expectations and a changed background of assumptions.

The new moral individualism would no doubt be unreasonable in Israel or in the new African and ex-colonial states, or wherever mobilization for an emergency is the condition of the survival of a new social order. But at least in the overdeveloped countries, in the United States, the Soviet Union and its satellites, and in Western Europe, it is not unreasonable to measure one’s activities while still young against a shorter time span and to reject the seemingly perpetual mobilization which the politics of confrontation requires. To surrender the ambitions that any individual may have for his own adequate private life, as being the recurrence of an ideal type, may seem an unneeded compromise with the determinism of technology and national power. The race for supreme national power is just as likely to destroy the social order in nuclear war, or in destruction of the environment, as to preserve it in stalemate.

Those who are intelligent and young are likely therefore to follow their experimental moral reasoning, having a different time scale in mind and seeing their own immediate inheritance as principally an inheritance of war, the arms race, and repression. Only a moratorium, time out from the use of accelerating technology as new national power, will seem to them to offer recurrence of typical experience on a recognizably human scale for their children. The so-called generation gap is, I think, principally this absence of a hitherto normal sense of being able to transmit to children an inherited moral culture which has at least been proved to be safe and to preserve normal life. Because their parents seem to have provided no safety for grandchildren, they refuse the normal process of imagining themselves occupying their parents’ positions.

The symbolism of the moratoria and mass meetings of these last few years seems to me now in retrospect very clear. The break evidently came with the realization that professors and deans of great universities, with their panoply of educated reason, could dismiss the critics of the Vietnam war as adolescent sentimentalists. The relation between reason and sentiment in politics and the nature of adult judgment in modern politics had to be rethought, because it seemed that the official reasoning was the computation of strained and stunted men, who to their younger critics had the look of overgrown schoolboys in Machiavellian dress.

The active, critical minority of students has been, on the whole, right in their judgment of events in the years 1965-70; and, in default of a comprehensive social theory, it has been reasonable also for them to build their movement of protest on the idea of a moratorium, of a period of confusion and arrest and redefinition, before it is too late. From their standpoint on the time scale, they may have no reasonable alternative.

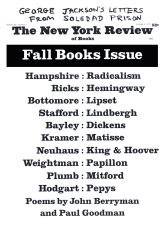

This Issue

October 8, 1970