Mr. Lawrence F. MacNamée researches into Shakespearian research, and has published a study of academic dissertations on Shakespeare written in Germany, Britain, and the US during the century up to 1964. During this time there were, he says, 681 successful these, 333 of them in the US and thirty-one in Britain. This last figure I cannot accept; for my reason tells me that however I may feel about it I cannot myself have supervised or examined the entire output.

However, certain trends are detectable, and perhaps trends are more interesting than mere numbers. In the earliest days there was a tendency to be strenuously philological, and emulation of the sciences produced poker-faced source studies, or inquiries into the syntax of Shakespeare’s infinitives. Later there was a lot of history of ideas, the fossilized remnants of which are still chipped out of paperbacks by enterprising students; and then there was allegory, mostly Christian, and imagery. This information I derive not from Mr. MacNamee directly, but from a rather horrifying though well-produced annual entitled Shakespearian Research Opportunities (which, as we can see, researches into research on Shakespearian research). S.R.O. reports all it can gather about the Shakespearian scene, from major editions to books about Elizabethan bastardy, and from the proper study of computers to glossolalia in Hamlet. It is where you ought to go to study the action.

The purpose of this review, which takes in only a dozen or so recent books, is obviously more modest; although the sample may seem too small to entitle me to speak of trends, I intend nevertheless to do so. For Shakespearian criticism is, I think, interesting in ways that have nothing to do with Shakespeare, and that are in the long run the business of cultural pathology. It is the understanding of all sensible men that there is far too much criticism around, and that most of it is rubbish; but the license to write it probably originated with Shakespearians. The right to say what you damn well choose about Shakespeare is felt, like the American right to bear arms, to be constitutional, though it leads to those lamentations one regularly finds in prefaces to books by authors fastidious only in these exordia.

The standards of Shakespeare criticism are still very much lower than those of, say, Milton criticism. The reasons, partly cultural, partly social and economic, will not emerge from a cursory review, but the fact remains that Shakespeare is the only important writer on whom anybody can write a book for no other cause than that he has a mind to do so; and the chances appear to be that he will find a publisher. It is also a fact that good critics tend to do worse with Shakespeare than with anybody else, not because of his inherent difficulty but because the climate of Shakespeare studies is so relaxing.

I don’t mean that this batch is particularly dim; in fact, it may suggest that at the highest level interesting changes are about to occur. We may be moving into a new era of Shakespeare criticism, and if we are it is a matter of interest not only to Shakespearians. The first ten titles listed above are all comfortably within the current orthodoxy—the one which, for the past forty years or so, has taken the place of the older philology, and is either a mixture, usually dilute, of history of ideas and “new” criticism, or a continuation more or less humanized of “scientific” factual research.

The last three, however, are different, and perhaps belong to the next orthodoxy. At first sight their main interest might seem to be closely related to the obsolete syntax-of-the-infinitive kind of thing; actually it is new, and still close enough to the critical achievements of the more recent period to use them freely. Mr. Rabkin, in the Introduction to his collection, talks about a Kuhnian “change of paradigm.” If Thomas Kuhn’s hypothesis—I mean the view that science does not move gradually to new positions but, by paying attention to facts hitherto ignored as unimportantly anomalous, leaps to a whole new position—if this really works for criticism we shall in due course see the old disciplinary matrices not so much systematically demolished as simply stranded, ignored, mopped up, if at all, only when the main thrust is over, as if intellectual history were a kind of Panzer attack on the future. I.A. Richards, writing about Jakobson’s little book, puts it differently but no less excitedly, for he thinks that this kind of linguistic criticism will improve not only our reading of Shakespeare but ourselves and our world.

Whether these claims, and these ways of making them, are justified is a question that can wait; but surely one can say, in general, that some major change is due. The kind of thing the old orthodoxy can say about Shakespeare is of small interest to the young; the new drama has altered their style of attending, and the conventions governing the older criticism, though they once seemed natural, are now known and recognized to be very arbitrary. This is true in all fields, I think, and perhaps especially in history of ideas; so that when some daring elder, like Mr. Howarth, gently questions the permanent truth and utility of Tillyard’s Elizabethan World Picture the reaction of the more spirited youth is likely to be one of astonishment that anyone should think it needed destroying.

Advertisement

Still, the great bulk of work will presumably continue, for some time, to be of the older style, and not only out of inertia, but because there is a need that can never be fully satisfied for the kind of inquiry that isn’t much affected by these paradigmatic alterations: reliable information of a primary sort, reliable texts, and much else. The Newest Criticism is ultimately just as dependent on it as the New. And my first ten titles contain a measure of this kind of work, as well as the secondary kind that grows from it: synoptic studies and popularizations. It may be unfortunate that the exceptional brilliance of the “new” in this list rather dims much of the old. It could of course be just as trivial and tedious as the worst of what it aims to replace.

To begin at the scholarly roots, the edition of Johnson’s criticism has naturally no ambitions beyond accuracy of text, completeness, and adequate annotation; it has nothing to do with the general reader, who will be far better served by W.K. Wimsatt’s excellent paperback,* and it is, as it must be, ponderous and minute. Johnson requires such attentions, though he himself addressed the educated general reader, and wrote for him what is still the best single essay on Shakespeare. “He that has read Shakespeare with attention,” he wrote long before publishing his edition, “will perhaps find little new in the crouded world,” adding that the poet’s “reputation is…safe, till human nature shall be changed.” He perhaps meant never, or at the apocalypse; and possibly he would still hold to this in our time.

Johnson had his faults. He is here duly charged with them, and especially with his failure to collate as many early editions as he promised. His work is messier than it should have been; but not because he wasn’t a sufficient scholar. The huge project was carried out, for the most part, very hastily, but it had as its strong foundation Johnson’s immense lexicographical labors. His first proposals for the edition were issued in 1745, twenty years before the book, and at that time he made himself a Shakespearian glossary, some of which got into the Dictionary. He knew a lot about the drama, and quite a lot about the Elizabethans; he used other scholars well, and was humane as well as clever in glossing hard passages. Nobody who has edited a play is in danger of underestimating the achievement of Johnson in this field, though the dissociation of scholar and man of letters had hardly begun. And the Yale editors were being useful as well as pious when they decided to include all but the most trifling of his notes. Johnson is still, if we think the qualities most desirable in a critic to be intelligence and industry, our best model.

Though they would not deny Johnson, the most learned of modern scholars would more naturally trace their ancestry back to Malone. F.P. Wilson—“probably,” as Helen Gardner says in her Preface to his posthumous papers, “the most learned Elizabethan scholar in the world”—was long associated with the Malone Society, of which the chief business is the transcription and editing of early dramatic manuscripts and books. Wilson was a professor, but the tradition in which he worked was not necessarily academic; his friends E.K. Chambers and W.W. Greg, obituarized in this book, were not attached to universities and knew nothing of routine teaching. He was less prolific than Chambers and probably less ingenious (in the full sense) than Greg, but like them he practiced a high, disinterested, and minute scholarship, and commanded an enormous range of information, having done the kind of reading that only a few men in any generation can or will undertake.

This was the more admirable in that he lived through and took part in several scholarly revolutions—two of them in Elizabethan bibliography, and at least one in the study of theatrical structures. This collection of Wilson’s work is weaker for the omission of his remarkable essay of 1945 on the New Bibliography; it is a historical survey of great importance, and Dame Helen had wanted to make it the centerpiece of the book. But Wilson had not fully brought it into line with the next bibliographical phase, associated with such names as Bowers and Hinman; and so she left it for separate publication. What takes its place in the present volume is much less interesting, being the material of the history plays and comedies that Wilson wrote for his unfinished volume of the unlucky Oxford History of English Literature.

Advertisement

Wilson’s slightest lecture would contain pertinent matter from books nobody else had read, and it is not surprising that these chapters have the same merit; but they are dull on the whole, partly because he was not really much interested in the possibilities, delusive or not, that opened out in the criticism of his time, and partly, of course, because the scheme of the History committed him to many pages of exposition in which an unenterprising lucidity takes precedence over all else. Some notion of the kind of scholar he was can be got from such pieces as “The Proverbial Wisdom of Shakespeare,” which is founded on his huge personal collection of proverbs; it supplements Tilley’s standard collection, and is precisely the kind of primary material that, in the slow course of time, feeds editors and critics; it belongs to that part of literary study in which knowledge really is cumulative, whatever is happening to the paradigms.

Wilson was thus a scholar’s scholar, with no immediate access to the common reader; Muriel Bradbrook is a scholar of another kind and has always had in mind the need for a more immediate dissemination of the learning necessary to good common reading. She has produced over the years a large body of writing, learned but accessible and occasionally adventurous, in the Elizabethan and Shakespearian fields. Her last book was about the players, and this one concerns Shakespeare’s theatrical craft. It describes the progression from medieval theater to the Globe, and Hamlet, here considered the height of Shakespeare’s theatrical achievement.

Miss Bradbrook’s notion of the Elizabethan theater is flatly unlike that of Frances Yates, as set forth in this journal [NYR, May 26, 1966] and in her book Theatre of the World; Bradbrook is much more down to earth, and her Burbage adapted the old public playing places without bothering about Dee’s Euclid, as Miss Yates argues. In fact she says that when they took the timbers across the river and built the Globe, the old emblematic theater was done for. Julius Caesar, a Globe play, breaks with the old concept of tragedy, and Hamlet, with its unsteady narrative and blurred certitudes, its revolutionary view of the theatrical past, was to come soon after. So too the old clown gave way to the new fool Armin—another change of paradigm. There were new theaters, new audiences, new kinds of play, and new kinds of acting; one could now have, as in Hamlet, an “action…hazardous, contingent, self-contained,” making wholly new demands and stepping into a modernism which, acquainted with their own modernisms, critics can perhaps only now begin to understand.

Although Miss Bradbrook thus touches on the excitements of the newer Shakespeare criticism, she is chiefly, as the new men are not, writing history. She invents a narrative, and only where the narrative is inadequate does she invent explanations, as for instance in the case of Hamlet. It is a very good method, and this is a good short book, which shows among other things how valuable it is for those who address the larger audience to have an easy command of all the archaeological and textual novelties of modern scholarship.

But there is a larger audience still, the paperback Shakespeare audience, and learning for them is usually digested more strenuously by the man dispensing it. Francis Fergusson’s book is largely made up of the necessarily simple introductions he wrote for the Laurel Shakespeare; he covers the whole oeuvre and provides prefatory material, interpolates commentary between the chronologically arranged introductions, and organizes the works into periods.

There are lots of books superficially like this, but Mr. Fergusson is a distinguished critic, a Dante scholar as well as a Shakespearian, and one hoped for rather more of this one. The essays on the plays seem to address a readership too unlearned to absorb anything of much interest, and Fergusson writes here as he would not anywhere else: “The large gallery of Dickensian local characters [in Henry IV, 2] has something to satisfy every taste.” The desperate fate of the Shakespeare critic is that he can be induced to consecrate to his most admired subject sentences he would not think fit for some minor novelist.

There are, of course, good things, as when we are told that Iago “has lost, not the intellect, but the good of the intellect”—one of the moments when Fergusson’s excessive preoccupation with the parallels between Shakespeare and Dante is rewarding; ordinarily it reduces the interest of the plays and narrows the contexts in which we are entitled to understand them. It hardly seems right for a book designed as an introduction; nor does the inadequate treatment of the Elizabethan theater, and the acceptance, without any attempt to defend it, of what is known as the Early Start theory, which pushes several plays back into the 1580s.

Sometimes there seems to be a conflict of interests, as when we are told that the “contrasting effects” in Hamlet will fall into place if we note that it is composed on medieval principles; and then that it is the most mysterious of plays, and that we must each form our own notion of its meaning. The second statement conforms with the Bradbrook argument above, and perhaps the Booth argument below, but it would be awkward to make it consistent with its immediate predecessor.

The truth is that books taking in the whole, or even a considerable part, of Shakespeare, are hard to write. Mr. Stampfer’s seems to me both ill-conceived and ill-written; the confused sophistication of the tone reflects a real uncertainty about what is being done and how to do it. Here is the last sentence of the book:

What is ineluctable in this coincidence [Coriolanus and the death of Shakespeare’s mother, which is supposed to have ended the “mature, bitter, middle period” that began with the death of his father] is how complex a knot of spirit, personal and professional, that tough, quiet, harassed worker, William Shakespeare, carried inside him for so many years, on whose taut equilibrium he projected play after play.

The problem of knowing exactly what this means hardly arises, since the prose sends out powerful signals telling us to ignore it. “And then his mother died. He absorbed it, slammed out another dramatic truth or two; but his knot of tumult had lost one of its driving pins.”

If that is acceptable, go ahead and consider Mr. Stampfer’s study of the typologies that shape Shakespeare’s plot and protagonists. He thinks there are three sorts of tragic hero (instead of the venerable two): the ethical, the willful, the political. All occur in Julius Caesar, a play to which Mr. Stampfer assigns the mental age of twelve. Julius Caesar is a parallel figure to Christ; and “by calling the murder of Caesar a sacrifice, with…overtones of parricide, we introduce an overtone of family killing into the excessive filicide of Titus Andronicus.” Excessive filicide is perhaps an interesting notion, but here it means only that there is in progress an unavailing struggle to make something, no matter what, new. This book belongs neither to the good Old Criticism (it is not well-informed itself, and will not inform anyone else), nor to the New described below. Good writers stumble on Shakespeare; let others beware.

Mr. Howarth wrote an interesting book on Eliot, and offers Shakespeare the tribute of gentlemanly prose. His book is made up of eight essays, the best a meditation on the semantics of Elizabethan gentleness; but even in that there are signs of licentious speculation, and soon we are being told that A Midsummer Night’s Dream is an allegory of English literature in Shakespeare’s time, and that Measure for Measure comments freely on James I’s Basilikon Doron. A pleasant, unsatisfying book, for all its arbitrariness possessing a sort of professional finish.

Mr. Auchincloss’s has not even that to commend it. It may seem extraordinary that this highly professional writer should, in the limited context of Shakespearian studies, lend himself so abjectly to the proposition that the one thing worse than professional musing is amateur musing; but if the pros themselves bother less about evidence, and daydream more shamelessly, when writing of Shakespeare, what can we expect? In fact Mr. Auchincloss isn’t particularly wild; he simply accepts that in this connection the threshold of what is intellectually tolerable is lowered. “How I love Lucio!” he cries; or observes of Lear that “Goneril and Regan are under no illusions as to his conduct; and left alone they immediately discuss how unreasonable he has been to cast Cordelia off.” He would not speak thus of a Henry James novel.

There is some mildly interesting talk, for example about how Shakespeare had sometimes to cope with bad données; but for the most part the effect is almost of a put-on: “I imagine [Shakespeare] would have been proud to know that the consort of Charles I occupied his house in Stratford for a brief period.” All this tends to show is that good minds are not at their best on Shakespeare; and this is an important aspect of Shakespeare criticism, which its historian—and it ought, alas, to have one—will have to explain as part of his huge and repellent task.

Can specialists, limiting themselves to a single issue, avoid disaster? Mr. Bartholomeusz, looking into the insights of the players, suggests that it is possible. This is an admirable work, covering productions almost from the first, as Simon Forman saw it, and dealing with everything from Davenant’s adaptations to Stanislavsky and beyond. Bartholomeusz thinks that although the players frequently obscure the text, they sometimes anticipate or emulate the sort of criticism called “practical,” which depends on intense scrutiny of the words. Thus Garrick paused at “angels” in

his virtues

Will plead like angels, trumpet- tongu’d, against

The deep damnation of his taking-off

—and was criticized for it; but he argued that “trumpet tongu’d” referred not only to the angels but to Duncan’s virtues, an early and simple example of that syntactic facing-both-ways which we associate with Empson.

Mr. Markels, having less material to occupy him, reminds us that to give a whole book to a play isn’t necessarily the answer. He is compelled to express his understanding of the whole Shakespearian gestalt before attending to his part of it, and hazy generalizations do the work of fact. Antony and Cleopatra on this view becomes an “attempt to confirm the insights of King Lear.” Since, in this play, Shakespeare’s divergent public and private versions of value and of the state converge, the author is obliged to trace the history of these views in earlier works. On the play itself he is uninteresting. What you and I may think one of the great moments in Shakespeare—Cleopatra’s

Lord of Lords,

Oh infinite Vertue, comm’st thou smiling from

The world’s great snare uncaught?

—is called “oddly inappropriate.” Markels has little sense of the “local activity” of verse, and although his view of the play is somewhat romantic, needing the frequent use of such words as “apotheosis,” his book rests more heavily on vague formulations: Antony “encompasses both the naturalism of death in King Lear and the symbolism of reconciliation in The Tempest.” The prose has a flat academic competence which cannot quite exclude absurdity: “In Antonio a good womb has borne a bad son.”

Mr. Hyman, whose early death deprives us of critical comment which was usually much more enlivening, is also working on one play, writing less about Othello than about critical pluralism—exhibiting five critical ways of looking at Iago’s motivation. These, plus—presumably—any number of others, may add up to the truth. The chosen five treat Iago as traditional villain, as devil, as image of the artist in his criminal aspect (Burke), as psychoanalytic exemplum (the handkerchief and her sweating palm are upward displacements of Desdemona’s genitals), as homosexual (a reading invented by Edwin Booth and secured in 1937 by Olivier, in consultation with Ernest Jones), and Machiavellian. There is lively detail here, and the book, though unimpressive, is brisk and capable. But its pluralism is naïve; it looks back over the old paradigm, and it is, at any rate as far as this review is concerned, time to begin a new.

As to that, it might seem that my remaining space should be chiefly given to Jakobson’s book, for which very large claims are made. But on reflection I think it better to attend first to the work of Mr. Stephen Booth. He turns up first in Mr. Rabkin’s collection, which, as I’ve said, makes explicit claims to Newness. Rabkin claims that he has got together authors “free from the increasingly deadening obligation to an old paradigm to reduce their works to meanings” (elegance we do not expect). This “community of new thinking,” founded on Gombrich, Meyer, Arnheim, Peckham, and others, is not sharply defined, but it produces some good pieces, notably one by Jonah Barish on “reversions” and “rejuvenations” of Elizabethan drama in our time, and another in which Max Bluestone demonstrates, from a study of Dr. Faustus, that “fundamental ontological oxymora are not for dramatic spectacle to resolve but to show,” which is actually less recondite than it sounds. But Booth’s essay on Hamlet is what counts.

The minute one begins to read Hamlet seriously one grows aware that it is devious in ways no other Shakespeare play (though some are very devious) can match. That the incidents and the language powerfully force the attention away from what “ought” to be its track has more than once been demonstrated from the first scene. But Booth does it with more resource and skill than anybody else, and then goes brilliantly on to prove the same point of the whole play. He dismisses the view that Hamlet is a muddle (one genuine but partial response) by arguing that it derives from the cultural bad habit of supposing that there must be discrepancies between the appearance and the reality, when the true business of the critic is simply to attend to what is being done. What the play does is to interrupt the syntax of exposition, confuse the audience’s focus, disappoint its expectations by digressing, hesitating, holding incoherencies in a researched coherency. For an attentive audience there is no certainty or comfort; the play is always saying what Hamlet said to Ophelia: “You should not have believed me.”

Hamlet, and the play itself, pretend madness or are mad, and then drift back into focus as if nothing had happened. So we have to cope with the “actual and continuing experience of perceiving a multitude of intense relationships in an equal multitude of different systems of coherence”; and from this we derive not only intellectual satisfaction but an intimacy with our own frailty of understanding and the absurdity of our normal expectations. Mr. Booth, extraordinarily sensitive to “local activity,” has also a remarkable grasp of the gross and scope of the thing, and this beautiful essay, in itself worth many books, may be the best place to go if you want to know what the best New in Shakespeare criticism is likely to be.

In his book on the sonnets Booth lets us see how he developed the methods which pay off in the essay. He is concerned, not with some uncontrollable pluralism, but with the ways in which a sonnet is organized “in a multitude of consistent and conflicting patterns—formal, logical, ideological, syntactic, rhythmic and phonetic.”

Here his immediate ancestors are Empson, and—in an extraordinary passage, here discerningly analyzed—C. S. Lewis; but he also pays his debt to David Masson, who worked alone in his phonetic field for years but, as Booth remarks, was prevented from getting through to an audience by his formidable and ugly machinery. There is such a thing as being too early, and Masson missed the wave of linguistics now breaking over criticism; but it is more important to understand that one of the dangers inherent in this situation is the overemployment of machinery. Booth avoids it skillfully.

John Crowe Ransom, in a famous essay, argued that the sonnets are so ill-constructed that in most of them there is no connection between the formal and logical structures. Booth replies that if you take a more sophisticated view of structure there is no such connection in any of them; but where Ransom finds weakness he finds strength. There may be, there is, a moment when one intuits in the complex mesh of conflicting patterns an order; and Booth says that such moments are the happiest the human mind can know, moments when it is beautifully poised on the threshold of comprehension, like, perhaps, the mind of the poet. These large claims suggest that criticism is regaining its confidence as it acquires new techniques, which it movingly represents as able to increase our happiness or mitigate our pain. Criticism may thus be both difficult and humane.

Booth’s analysis of the sonnets on these new principles seems to me of a high order of criticism and humanity. A much too simple instance will have to do; in the first two lines of Sonnet 33:

Full many a glorious morning have I seen

Flatter the mountain tops with sovereign eye

the first line seems syntactically complete until the second is added; this “violation of the reader’s confidence in his expectations about a syntactical pattern” is enormously augmented, and not only syntactically, in the sequel, and the whole business of violated expectations is the theme of the sonnet. What the interplay of all these structures implies is “incessant intellectual motion” in the reader, though he is at best subliminally conscious of them. The analyst can study them in the text, and begin to describe the intershifting gestalten the reader struggles with, moving abruptly in and out of the different but interlocked systems with more joy than knowledge.

He may not be as conscious of the elaborate phonetic structure of Sonnet 129 (“The expense of spirit in a waste of shame”) as he is of its formal and logical structures; but as Booth remarks, the equation of the expense of spirit with lust “is logically only an assertion, but phonetically it is proved.” The interplay of rhyme and logical stops, the cross patterns of phonetic and rhythmic echoes are what the sonnet does, and what we follow. Shakespeare’s success is ours, for, as Booth puts it in a characteristic phrase, he gives us “the sense both that we know what cannot be known and that what we know is the unknowable thing we want to know and not something else”; of course, we have to work for this happiness.

It could, perhaps should, be said of this book that it is only a beginning; that sometimes what is referred to is not very clearly defined; that once we begin to look in this way we shall find a copious supply of new forms of hocus-pocus. For the question arises, in what sense are these patterns simultaneously there; but I doubt if Booth cares, being concerned with difficult operations of the mind and with the acceptability of these extremely complex linguistic structures. His work takes him close to technical linguistics but never over the line, and one thinks the more of him for having shown, in the Hamlet essay, that he can adapt his way of looking to very much longer works than sonnets, works of which the formal patterns are enormously more variable and resistant to formulae. Any way I can look at it, his achievement seems to me extraordinarily impressive.

Roman Jakobson, with a co-author Lawrence G. Jones, has also been attending, with formidable analytical equipment, to a sonnet. A few years ago he produced, with Claude Lévi-Strauss, a staggering study of Baudelaire’s “Les Chats,” also a sonnet. Now, without benefit of anthropological polarities, Shakespeare’s Sonnet 129 is the subject. The analysis is very thorough and starts with what Booth would call the “formal” structure, namely the prescribed rhyme scheme of the sonnet; but it immediately grows subtle beyond our wont. The four strophic units of the sonnet exhibit three kinds of binary correspondence: alternation (abab) in the odd strophes; framing (abba) in the outer strophes; neighborhood (aabb) in the anterior strophes. These are in opposition to the even, the inner, and the posterior. The first seven lines are centripetal, the last seven centrifugal; in the former the breaks fall after the fifth syllable, in the latter after the fourth and/or sixth.

The network of binary oppositions extends from these formal relations to a large array of syntactic and phonetic systems; for example in infinitives, in the distribution of substantives and adjectives (“all seventeen substantives of the odd strophes are abstract, all six substantives of the even strophes are concrete”), in conjunctions, which are copulative in the odd and adversative in the even strophes, and in such phonetic characteristics as vowels of tense or lax onset. The whole sonnet becomes a complex network of conflicts, couplet against quatrain, outer against inner, center against marginals; and all of them turn on the central distich (7-8) which differs from the rest of the poem in lacking grammatical parallelisms, but also in having the only simile in the poem.

This is the merest selection of the material accumulated to justify the claim that the sonnet has an “amazing external and internal structuration palpable to any responsive and unprejudiced reader.” The authors think this will tell against readings founded on too narrow a response, but also against readings that are too free, for the poem has “a cogent and mandatory structure.” This kind of analysis will precisely define the unity of the poem and exclude all readings which it does not substantiate.

Thus the claim is that an intelligent reading can be exposed in microscopic detail, the proper motions of the reader’s mind laid bare by showing the structures, linguistic and semantic, that overlap in the text. It isn’t only the “mandatory” structure that is exposed, but the whole process of response. That is why I. A. Richards in his eulogy (Times Literary Supplement, May 28, 1970) calls Jakobson’s work “a landmark in the long-awaited approach of descriptive linguistics to the account of poetry.” Prompted by another article of Jakobson’s, he sees some affinities between these studies and modern genetics. He also calls them “a powerful helping hand in this time of frightened and bewildered disaffection.” Here is a way to make poetry once more what it has been, one of “mankind’s chief sustainers”; understanding how it works “may well be a practical aid towards saner policies.” And if we are tempted to think that the degree of order posited by Jakobson is “preternatural,” it is up to us to revise our notions as to what is natural.

Richards usefully distinguishes, in the poet, knowledge about and know-how; there is a similar distinction to be made in respect of the reader, and Jakobson is increasing everybody’s knowledge about. I suppose the genetic link is that the transmission, by genetic means, of very complex information, is a matter of unconscious know-how and that knowledge about it is at present increasing at a great rate. In both forms of study knowledge can intervene in the operations of know-how, and Richards sees the danger of this, fearing that “busy-work” may replace “concern with poetry,” that works which lend themselves less readily to this kind of treatment may be thought therefore inferior, and that poets will let knowledge about interfere with know-how. Jakobson’s methods derive from general linguistics and are unlikely to be a perfect fit for poetry; they leave a lot out, if only because linguistics as yet cannot cope with semantic as distinct from phonetic and grammatical structures in anything like the necessary fullness. But with all these reservations Richards finds it possible to believe that the new methods will increase our discernment as readers, and so improve the quality of life.

Skeptics may not find this tribute very convincing. One wants to be liberal, of course, but, asks F. W. Bateson, would you let your sister marry a linguist? The answer is that precisely this miscegenation is the answer. Linguistic insights modified, linguistic techniques diluted, may and perhaps ought to be the instruments of the next era of literary criticism. Jakobson is not in himself the answer, and perhaps the modifications will be difficult to make. That there are actual achievements, as in the analysis of certain kinds of narrative, I take for granted; but poetry is nearer the quick of language itself, and the grand new instruments can be brought to it without a full understanding that its proximity may conceal essential differences from the material for which the instruments were designed.

There is a further practical difficulty, namely that if you are dealing with anything very much longer than a sonnet the apparatus becomes burdensome. So far as I know Jakobson has treated nothing longer, and nothing with a less palpable formal organization. Yet it is plain that if the utility of the method is to be established, longer works, with obscurer shapes, will have to be tackled; the apparatus will have to be simplified and the approach made less strenuous and minute. That is why the less technical approach of Booth, and his success with Hamlet, strikes me as finally more important than Jakobson’s tour de force. Opinion will vary on this; what seems certain is that this new criticism is necessary. In the critical books here reviewed some, as I said, belong to the old “paradigm,” and whatever their merits one is conscious always of having to try to be interested in them. But Booth and Jakobson require an alertness to their own shifting patterns which is analogous to the requirement they find in the works discussed. They really are talking about something that matters, now, to all intelligent people. There can, it seems, be new excitements even in Shakespeare criticism.

129

TH’expence of Spirit in a wafte of fhame

Is luft in action, and till action, luft

Is periurd, murdrous, blouddy full of blame,

Sauage, extreame, rude, cruell, not to truft,

Inioyd no fooner but difpifed ftraight,

Paftreafon hunted, and no fooner had

Paftreafon hated as a fwollowed bayt,

On purpofe layd to make the taker mad.

Made In purfut and in poffeffion of,

Had, hauing, and in queft, to haue extreame,

A bliffe in proofe and proud and very wo,

Before a ioy propofd behind a dreame,

All this the world well knowes yet none knowes well.

To fhun the heauen that leads men to this hell.

My

Sonnet 129, from the 1609 Quarto.

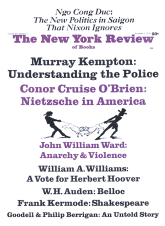

This Issue

November 5, 1970

-

*

Samuel Johnson on Shakespeare, Hill and Wang, $1.50.

↩