Nietzsche, it is usually held, was purely a man of thought and letters, and he was certainly never involved in practical politics: his political thought is generally considered to come a long way, in importance, after his contributions to psychology, German prose, and the critique of ethics.

Such classifications have their uses, especially for librarians, but it may also be useful to ignore them. All writing that we know—even the writing of Samuel Beckett—is a form of social communication, a cryptic signaling going on in society and history. And this signaling is not going along a narrow channel, as the old New Criticism would perhaps have preferred.

It does not usually work, even among strong and trained intelligences, through the concentration of maximum attention on a series of texts—that is training or discipline at best; it may also be a game or a refuge. But the real creative and destructive process of communication goes on in jumps, and crisscross jumps at that. Each mind and each age take from the messages what they can absorb and feel they need, and in this process it is irrelevant whether the signaler or the receiver is classified as politician, poet, or philosophical writer.

Machiavelli was more important for Nietzsche than were the “purer” men of letters of the sixteenth century. Nietzsche, and later Burke, and an idealized picture of Renaissance Italy were more important in the development of Yeats’s imagination than were any of the poets of those places and times. A few lines of poetry, the selected aphorisms of a retired man of letters, may liberate the demon of a charismatic political leader. The whole imaginative and intellectual life of a culture is one interacting field of force.

It is necessary to emphasize this particularly in the case of Nietzsche because people have gone to great pains to insulate Nietzsche, to isolate him from the culture in which he has been so potent a force. There is, we are told, a legitimate way of understanding Nietzsche, and also illegitimate ways which twist his true meaning. The key to the legitimate way is a spiritual one. When Nietzsche praises, as he so often does, war and cruelty, we are told we must understand him as calling for spiritual struggle and a stern mastery over the self.

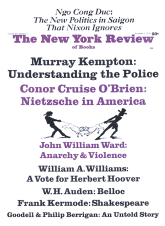

This Issue

November 5, 1970

-

*

All of the following books have been translated and/or edited by Walter Kaufmann: On the Genealogy of Morals: Ecce Homo, Vintage, $1.95 (paper); Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, Vintage, $1.65 (paper); Birth of Tragedy: Case of Wagner, Vintage, $1.65 (paper); Portable Nietzsche, Viking, $5.50, $1.95 (paper); Thus Spake Zarathustra, Viking, $1.45 (paper); The Will to Power, Random House, $10.00, $2.95 (paper); and, most recently, Basic Writings of Nietzsche, Modern Library, $4.95.

↩