In response to:

Power to the Caribbean People from the September 3, 1970 issue

To the Editors:

Mr. Naipaul [NYR, September 3] uses his gifts of satire and irony, much praised by the metropolitan critics, to ridicule socalled Black Power manifestations in the Caribbean. More, he goes on to say that the islanders, black, poor, and lacking in resources, are condemned to everlasting sterility. One never gets the impression that here is a West Indian writer, whose past is the plantation and slavery, turning his eye on contemporary events and grappling with the enormous difficulties facing the West Indies. Naipaul’s response is a superior sneer and a condescension worthy of a colonial governor. Try as he might Naipaul can’t get away from the Middle Passage that formed us. And if black and East Indian children have their fantasies to protect them from reality, Naipaul has his satire. Little difference.

Being a Trinidadian I will consider Naipaul’s remarks from this point of view, but with slight modification the same can be said of almost any other island.

The economic facts are these. The oil industry, which provides the largest source of revenue, is American-owned. The sugar estates, which employ the largest number of people, are controlled by the British firm Tate & Lyle. Citrus, cocoa, and banana estates are owned by expatriate or absentee landlords. Thus white foreigners control the economic activity of the island. In addition light industry is attracted to the island by tax concessions on imported goods, materials, and profits of up to five years. Hotels and private houses have been built and are being built at the best beaches, and in some instances natives are not allowed to go there. The white minority form the spearhead of such activity and benefit most from it. The government ensures that the atmosphere is conducive to such exploitation. I shall consider Naipaul’s analysis of the situation in the light of these facts.

Naipaul says, “These islanders are disturbed. They already have black government and black power, but they want more. They want something more than politics. Like the dispossessed peasantry of medieval Europe, they await crusades and messiahs.” And he goes on to equate the recent Black Power demonstrations and the leaders with the longed for crusades and messiahs. To claim that there is black power in any of the islands is ludicrous in view of the economic situation which I have outlined above in the case of Trinidad. For having a black government, a national anthem, and a flag does not mean that we have control over our destiny and the ability to create the type of political, social, and educational institutions that are best suited to our needs. The present neocolonial arrangements exclude this. And Black Power demonstrations, far from being “excitement,” “rage,” “drama,” “style,” as Naipaul derisively refers to them, are an inchoate protest against dire economic and racial exploitation.

The enemy may be the past, slavery, and colonial neglect, as Naipaul asserts, but it is also the present. The phantom enemies—“racial minorities, elites, white niggers”—are real enough if he will take the trouble to find out. Who is the enemy if not the foreign investor? And what is one to call the local whites and middle-class blacks who benefit from this economic and racial exploitation?

If Naipaul is contemptuous and arrogant about present political developments he is even more scornful about future prospects. Consider this:

The island blacks will continue to be dependent on the books, films, and goods of others; in this important way they will continue to be half-made societies of a dependent people; the Third World’s third world. They will forever consume; they will never create. They are without material resources; they will never develop the higher skills.

And further on the people, “black, East Indian, white, sense themselves condemned, not necessarily as individuals, but as a community, to an inferiority of skill and achievement.” West Indians—not Naipaul, of course—feel themselves condemned. By whom? Naipaul.

The above passage is strong language indeed, and it is here we come to the crucial point for Naipaul and for us. For 300 years of economic exploitation and cultural indoctrination have shaped our mental outlook. Europe defined what civilization is and this is what Naipaul accepts. In the face of European achievement in art, literature, and science, what have the descendants of slaves and indentured laborers created? What have they to offer? Cesaire puts it succinctly:

We have nothing to do in the world.

We are the parasites of the world.

Our job is to keep in step with the world.

Hence Naipaul’s despair and bitter hatred of the Caribbean.

To sum up, the political, economic, and social life is rotten from Jamaica to Guyana. It is dominated by foreign interests, ruled by corrupt governments and shored up by the local white business communities who have vested interests in the status quo. Nothing else can account for the unrest in the Caribbean today. And if the young people turn to Cuba it is because the Cubans have demonstrated that there is an alternative to the system imposed on us.

A. D. H. Jones

London

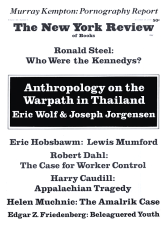

This Issue

November 19, 1970