I

The university graduate has been schooled for selective service among the rich of the world. Whatever his or her claims of solidarity with the Third World, each American college graduate has had an education costing an amount five times greater than the median life income of half of humanity. A Latin American student is introduced to this exclusive fraternity by having at least 350 times as much public money spent on his education as on that of his fellow citizens of median income. With very rare exceptions, the university graduate from a poor country feels more comfortable with his North American and European colleagues than with his non-schooled compatriots, and all students are academically processed to be happy only in the company of fellow consumers of the products of the educational machine.

The modern university confers the privilege of dissent on those who have been tested and classified as potential money makers or power holders. No one is given tax funds for the leisure in which to educate himself or the right to educate others unless at the same time he can also be certified for achievement. Schools select for each successive level those who have, at earlier stages in the game, proved themselves good risks for the established order. Having a monopoly on both the resources for learning and the investiture of social roles, the university co-opts the discoverer and the potential dissenter. A degree always leaves its indelible price tag on the curriculum of its consumer. Certified college graduates fit only into a world which puts a price tag on their heads, thereby giving them the power to define the level of expectations in their society. In each country, the amount of consumption by the college graduate sets the standard for all others; if they would be civilized people on or off the job, they will aspire to the style of life of college graduates.

The university thus has the effect of imposing consumer standards at work and at home, and it does so in every part of the world and under every political system. The fewer university graduates there are in a country, the more their cultivated demands are taken as models by the rest of the population. The gap between the consumption of the university graduate and that of the average citizen is even wider in Russia, China, and Algeria than in the United States. Cars, airplane trips, and tape recorders confer more visible distinction in a socialist country where only a degree, and not just money, can procure them.

The ability of the university to fix consumer goals is something new. In many countries the university acquired this power only in the Sixties, as the delusion of equal access to public education began to spread. Before that the university protected an individual’s freedom of speech, but did not automatically convert his knowledge into wealth. To be a scholar in the Middle Ages meant to be poor, even a beggar. By virture of his calling, the medieval scholar learned Latin, became an outsider worthy of the scorn as well as the esteem of peasant and prince, burgher and cleric. To get ahead in the world, the scholastic first had to enter it by joining the civil service, preferably that of the Church. The old university was a liberated zone for discovery and the discussion of ideas both new and old. Masters and students gathered to read the texts of other masters, now long dead, and the living words of the dead masters gave new perspective to the fallacies of the present day. The university was then a community of academic quest and endemic unrest.

In the modern multiversity, this community has fled to the fringes, where it meets in a pad, a professor’s office, or the chaplain’s quarters. The structural purpose of the modern university has little to do with the traditional quest. Since Gutenberg, the exchange of disciplined, critical inquiry has, for the most part, moved from the “chair” into print. The modern university has forfeited its chance to provide a simple setting for encounters which are both autonomous and anarchic, focused yet unplanned and ebullient, and has chosen instead to manage the process by which so-called research and instruction are produced.

The American university, since Sputnik, has been trying to catch up with the body count of Soviet graduates. Now the Germans are abandoning their academic tradition and are building “campuses” in order to catch up with the Americans. During the present decade they want to increase their expenditure for grammar and high schools from 14 to 59 billion DM, and more than triple expenditures for higher learning. The French propose by 1980 to raise to 10 percent of their GNP the amount spent on schools, and the Ford Foundation has been pushing poor countries in Latin America to raise per capita expenses for “respectable” graduates toward North American levels. Students see their studies as the investment with the highest monetary return, and nations see them as a key factor in development.

Advertisement

For the majority who primarily seek a college degree, the university has lost no prestige, but since 1968 it has visibly lost standing among its believers. Students refuse to prepare for war, pollution, and the perpetuation of prejudice. Teachers assist them in their challenge to the legitimacy of the government, its foreign policy, education, and the American way of life. More than a few reject degrees and prepare for a life in a counter-culture, outside the certified society. They seem to choose the way of medieval fraticelli and alumbrados of the Reformation, the hippies and dropouts of their day. Others recognize the monopoly of the schools over the resources which they need to build a countersociety. They seek support from each other to live with integrity while submitting to the academic ritual. They form—so to speak—hotbeds of heresy right within the hierarchy.

Large parts of the general population, however, regard the modern mystic and the modern heresiarch with alarm. They threaten the consumer economy, democratic privilege, and the self-image of America. But they cannot be wished away. Fewer and fewer can be reconverted by patience or co-opted by subtlety—for instance, by appointing them to teach their heresy. Hence the search for means which would make it possible either to get rid of dissident individuals or to reduce the importance of the university which serves them as a base for protest.

The students and faculty who question the legitimacy of the university, and do so at high personal cost, certainly do not feel that they are setting consumer standards or abetting a production system. Those who have founded such groups as the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars and the North American Congress on Latin America (NACLA) have been among the most effective in changing radically the perceptions of the realities of foreign countries for millions of young people. Still others have tried to formulate Marxian interpretations of American society or have been among those responsible for the flowering of communes. Their achievements add new strength to the argument that the existence of the university is necessary to guarantee continued social criticism.

There is no question that at present the university offers a unique combination of circumstances which allows some of its members to criticize the whole of society. It provides time, mobility, access to peers and information, and a certain impunity: privileges not equally available to other segments of the population. But the university provides this freedom only to those who have already been deeply initiated into the consumer society and into the need for some kind of obligatory public schooling.

The school system today performs the threefold function common to powerful churches throughout history. It is at the same time the repository of society’s myth; the institutionalization of that myth’s contradictions; and the locus of the ritual which reproduces and veils the disparities between myth and reality. Today the school system, and especially the university, provides ample opportunity for criticism of the myth and for rebellion against its institutional perversions. But the ritual which demands tolerance of the fundamental contradictions between myth and institution still goes largely unchallenged, for neither ideological criticism nor social action can bring about a new society. Only disenchantment with and detachment from the central social ritual and reform of that ritual can bring about radical change.

The American university has become the final stage of the most all-encompassing initiation rite the world has ever known. No society in history has been able to survive without ritual or myth, but ours is the first which has needed such a dull, protracted, destructive, and expensive initiation into its myth. We cannot begin a reform of education unless we first understand that neither individual learning nor social equality can be enhanced by the ritual of schooling. We cannot go beyond the consumer society unless we first understand that obligatory public schools inevitably reproduce such a society, no matter what is taught in them.

The project of de-mythologizing which I propose cannot be limited to the university alone. Any attempt to reform the university without attending to the system of which it is an integral part is like trying to do urban renewal in New York City from the twelfth story up. Most current college level reform looks like the building of high-rise slums. Only a generation which grows up without obligatory schools will be able to re-create the university.

II

The Myth of Institutionalized Values

School initiates the Myth of Unending Consumption. This modern myth is grounded in the belief that process inevitably produces something of value and, therefore, production necessarily produces demand. School teaches us that instruction produces learning. The existence of schools produces the demand for schooling. Once we have learned to need school, all our activities tend to take the shape of client relationships to other specialized institutions. Once the self-taught man or woman has been discredited, all nonprofessional activity is rendered suspect. In school we are taught that valuable learning is the result of attendance; that the value of learning increases with the amount of input; and, finally, that this value can be measured and documented by grades and certificates.

Advertisement

In fact, learning is the human activity which least needs manipulation by others. Most learning is not the result of instruction. It is rather the result of unhampered participation in a meaningful setting. Most people learn best by being “with it,” yet school makes them identify their personal, cognitive growth with elaborate planning and manipulation.

Once a man or woman has accepted the need for school, he or she is easy prey for other institutions. Once young people have allowed their imaginations to be formed by curricular instruction, they are conditioned to institutional planning of every sort. “Instruction” smothers the horizon of their imaginations. They cannot be betrayed, but only short-changed, because they have been taught to substitute expectations for hope. They will no longer be surprised for good or ill by other people, because they have been taught what to expect from every other person who has been taught as they were. This is true in the case of another person or in the case of a machine.

This transfer of responsibility from self to institution guarantees social regression, especially once it has been accepted as an obligation. I saw this illustrated when John Holt recently told me that the leaders of the Berkeley revolt against Alma Mater had later “made” her faculty. His remark suggested the possibility of a new Oedipus story—Oedipus the Teacher, who “makes” his mother in order to engender children with her. The man addicted to being taught seeks his security in compulsive teaching. The woman who experiences her knowledge as the result of a process wants to reproduce it in others.

III

The Myth of Measurement of Values

The institutionalized values school instills are quantified ones. School initiates young people into a world where everything can be measured, including their imaginations, and, indeed, man himself.

But personal growth is not a measurable entity. It is growth in disciplined dissidence, which cannot be measured against any rod, or any curriculum, nor compared to someone else’s achievement. In such learning one can emulate others only in imaginative endeavor, and follow in their footsteps rather than mimic their gait. The learning I prize is immeasurable re-creation.

School pretends to break learning up into subject “matters,” to build into the pupil a curriculum made of these prefabricated blocks, and to gauge the result on an international scale. Men and women who submit to the standard of others for the measure of their own personal growth soon apply the same ruler to themselves. They no longer have to be put in their place, but put themselves into their assigned slots, squeeze themselves into the niche which they have been taught to seek, and, in the very process, put their fellows into their places, too, until everybody and everything fits.

Men and women who have been schooled down to size let unmeasured experience slip out of their hands. To them, what cannot be measured becomes secondary, threatening. They do not have to be robbed of their creativity. Under instruction, they have unlearned to “do” their thing or “be” themselves, and value only what has been made or could be made.

Once men and women have the idea schooled into them that values can be produced and measured, they tend to accept all kinds of rankings. There is a scale for the development of nations, another for the intelligence of babies, and even progress toward peace can be calculated according to body count. In a schooled world, the road to happiness is paved with a consumer’s index.

IV

The Myth of Packaging Values

School sells curriculum—a bundle of goods made according to the same process and having the same structure as other merchandise. Curriculum production for most schools begins with allegedly scientific research, on whose basis educational engineers predict future demand and tools for the assembly line, within the limits set by budgets and taboos. The distributor-teacher delivers the finished product to the consumer-pupil, whose reactions are carefully studied and charted to provide research data for the preparation of the next model, which may be “ungraded,” “student-designed,” “team-taught,” “visually-aided,” or “issue-centered.”

The result of the curriculum production process looks like any other modern staple. It is a bundle of planned meetings, a package of values, a commodity whose “balanced appeal” makes it marketable to a sufficiently large number to justify the cost of production. Consumer-pupils are taught to make their desires conform to marketed values. Thus they are made to feel guilty if they do not behave according to the predictions of consumer research by getting the grades and certificates that will place them in the job category they have been led to expect.

Educators can justify more expensive curricula on the basis of their observation that learning difficulties rise proportionately with the cost of the curriculum. This is an application of Parkinson’s Law that work expands with the resources available to do it. This law can be verified on all levels of school: for instance, reading difficulties have been a major issue in French schools only since their per capita expenditures have approached US levels of 1950—when reading difficulties became a major issue in US schools.

In fact, healthy students often redouble their resistance to teaching as they find themselves more comprehensively manipulated. This resistance is not due to the authoritarian style of a public school or the seductive style of some free schools, but to the fundamental approach common to all schools—the idea that one person’s judgment should determine what and when another person must learn.

V

The Myth of Self-Perpetuating Progress

Even when accompanied by declining returns in learning, paradoxically, rising per capita instructional costs increase the value of the pupil in his or her own eyes and on the market. At almost any cost, school pushes the pupil up to the level of competitive curricular consumption, into progress to ever higher levels. Expenditures to motivate the student to stay on in school skyrocket as he climbs the pyramid. On higher levels they are disguised as new football stadiums, chapels, or programs called International Education. If it teaches nothing else, school teaches the value of escalation: the value of the American way of doing things.

The Vietnam war fits the logic of the moment. Its success has been measured by the numbers of persons effectively treated by cheap bullets delivered at immense cost, and this brutal calculus is unashamedly called “body count.” Just as business is business, the never ending accumulation of money, so war is killing—the never ending accumulation of dead bodies. In like manner, education is schooling, and this openended process is counted in pupilhours. The various processes are irreversible and self-justifying. By economic standards, the country gets richer and richer. By death-accounting standards, the nation goes on winning its war forever. And by school standards, the population becomes increasingly educated.

School programs hunger for progressive intake of instruction, but even if the hunger leads to steady absorption it never yields the joy of knowing something to one’s satisfaction. Each subject comes packaged with the instruction to go on consuming one “offering” after another, and last year’s wrapping is always obsolete for this year’s consumer. The textbook racket builds on this demand. Educational reformers promise each new generation the latest and the best, and the public is schooled into demanding what they offer. Both the dropout who is forever reminded of what he or she missed and the graduate who is made to feel inferior to the new breed of student know exactly where they stand in the ritual of rising deceptions and continue to support a society which euphemistically calls the widening frustration gap a “revolution of rising expectations.”

But growth conceived as open-ended consumption—eternal progress—can never lead to maturity. Commitment to unlimited quantitative increase vitiates the possibility of organic development.

VI

Ritual Game and the New World Religion

The school-leaving age in developed nations outpaces the rise in life expectancy. The two curves will intersect in a decade and create a problem for Jessica Mitford and professionals concerned with “terminal education.” I am reminded of the late Middle Ages, when the demand for Church services outgrew a lifetime, and “Purgatory” was created to purify souls under the Pope’s control before they could enter eternal peace. Logically, this led first to a trade in indulgences and then to an attempt at Reformation. The Myth of Unending Consumption now takes the place of belief in life everlasting.

Arnold Toynbee has pointed out that the decadence of a great culture is usually accompanied by the rise of a new World Church which extends hope to the domestic proletariat while serving the needs of a new warrior class. School seems eminently suited to be the World Church of our decaying culture. No institution could better veil from its participants the deep discrepancy between social principles and social reality in today’s world. Secular, scientific, and death-denying, it is of a piece with the modern mood. Its classical, critical veneer makes it appear pluralist if not antireligious. Its curriculum both defines science and is itself defined by so-called scientific research. No one completes school—yet. It never closes its doors on anyone without first offering him one more chance: at remedial, adult, and continuing education.

School serves as an effective creator and sustainer of social myth because of its structure as a ritual game of graded promotions. Introduction into this gambling ritual is much more important than what or how something is taught. It is the game itself that schools, that gets into the blood and becomes a habit. A whole society is initiated into the Myth of Unending Consumption of services. This happens to the degree that token participation in the open-ended ritual is made compulsory and compulsive everywhere. School directs ritual rivalry into an international game which obliges competitors to blame the world’s ills on those who cannot or will not play. School is a ritual of initiation which introduces the neophyte to the sacred race of progressive consumption, a ritual of propitiation whose academic priests mediate between the faithful and the gods of privilege and power, a ritual of expiation which sacrifices its dropouts, branding them as scapegoats of underdevelopment.

Even those who spend at best a few years in school—and this is the overwhelming majority in Latin America, Asia, and Africa—learn to feel guilty because of their underconsumption of schooling. In Mexico six grades of school are legally obligatory. Children born into the lower economic third have only two chances in three to make it into the first grade. If they make it, they have four chances in 100 to finish obligatory schooling by the sixth grade. If they are born into the middle third group, their chances increase to twelve out of 100. With these rules, Mexico is more successful than most of the other twenty-five Latin American republics in providing public education.

Everywhere, all children know that they were given a chance, albeit an unequal one, in an obligatory lottery, and the presumed equality of the international standard now compounds their original poverty with the selfinflicted discrimination accepted by the dropout. They have been schooled to the belief in rising expectations and can now rationalize their growing frustration outside school by accepting their rejection from scholastic grace. They are excluded from Heaven because, once baptized, they did not go to church. Born in original sin, they are baptized into first grade, but go to Gehenna (which in Hebrew means “slum”) because of their personal faults. As Max Weber traced the social effects of the belief that salvation belonged to those who accumulated wealth, we can now observe that grace is reserved for those who accumulate years in school.

VII

The Coming Kingdom: the Universalization of Expectations

School combines the expectations of the consumer expressed in its claims with the beliefs of the producer expressed in its ritual. It is a liturgical expression of a world-wide “cargo cult,” reminiscent of the cults which swept Melanesia in the Forties, which injected cultists with the belief that, if they but put on a black tie over their naked torsos, Jesus would arrive in a steamer bearing an icebox, a pair of trousers, and a sewing machine for each believer.

School fuses the growth in humiliating dependence on a master with the growth in the futile sense of omnipotence that is so typical of the pupil who wants to go out and teach all nations to save themselves. The ritual is tailored to the stern work habits of the hardhats, and its purpose is to celebrate the myth of an earthly paradise of never ending consumption, which is the only hope for the wretched and dispossessed.

Epidemics of insatiable this-worldly expectations have occurred throughout history, especially among colonized and marginal groups in all cultures. Jews in the Roman Empire had their Essenes and Jewish messiahs, serfs in the Reformation their Thomas Münzer, dispossessed Indians from Paraguay to Dakota their infectious dancers. These sects were always led by a prophet, and limited their promises to a chosen few. The school-induced expectation of the kingdom, on the other hand, is impersonal rather than prophetic, and universal rather than local. Man has become the engineer of his own messiah and promises the unlimited rewards of science to those who submit to progressive engineering for his reign.

VIII

The New Alienation

School is not only the New World Religion. It is also the world’s fastest growing labor market. The engineering of consumers has become the economy’s principal growth sector. As production costs decrease in rich nations, there is an increasing concentration of both capital and labor in the vast enterprise of equipping man for disciplined consumption. During the past decade, capital investments directly related to the school system rose. Disarmament would only accelerate the process by which the learning industry moves to the center of the national economy. School gives unlimited opportunity for legitimated waste, so long as its destructiveness goes unrecognized and the cost of palliatives goes up.

If we add those engaged in full-time teaching to those in full-time attendance, we realize that this so-called superstructure has become society’s major employer. In the US sixty-two million people are in school and eighty million at work elsewhere. This is often forgotten by neo-Marxist analysts who say that the process of de-schooling must be postponed or bracketed until other disorders, traditionally understood as more fundamental, are corrected by an economic and political revolution. Only if school is understood as an industry can revolutionary strategy be planned realistically. For Marx, the cost of producing demands for commodities was barely significant. Today, most human labor is engaged in the production of demands that can be satisfied by industry which makes intensive use of capital. Most of this is done in school.

Alienation, in the traditional scheme, was a direct consequence of work becoming wage-labor which deprived man of the opportunity to create and be re-created. Now young people are pre-alienated by schools that isolate them from the world of work and pleasure. School makes alienation preparatory to life, thus depriving education of reality and work of creativity. School prepares for the alienating institutionalization of life by teaching the need to be taught. Once this lesson is learned, people lose their incentive to grow in independence; they no longer find relatedness attractive, and close themselves off to the surprises which life offers when it is not predetermined by institutional definition. And school directly or indirectly employs a major portion of the population. School either keeps men and women for life or makes sure that they will be kept by some institution.

The New World Church is the knowledge industry, both purveyor of opium and the workbench during an increasing number of the years of an individual’s life. De-schooling is, therefore, at the root of any movement for human liberation.

IX

The Revolutionary Potential of De-Schooling

Of course, school is not, by any means, the only modern institution which has as its primary purpose the shaping of man’s vision of reality. Advertising, mass media, and the design components of engineered products play their part in the institutional manipulation of man’s demands. But school enslaves more profoundly and more systematically, since only school is credited with the principal function of forming critical judgment and, paradoxically, tries to do so by making learning about oneself, about others, and about nature depend on a pre-packaged process. School touches us so intimately that none of us can expect to be liberated from it by something else. We can only imagine other schools.

Many self-styled revolutionaries are victims of school. They see even “liberation” as the product of an institutional process. Only liberating oneself from school will dispel such illusions. The discovery that most learning requires no teaching can be neither manipulated nor planned. Each of us is personally responsible for his or her own de-schooling, and only we have the power to do it. No one can be excused if he fails to liberate himself from schooling. People could not free themselves from the Crown until at least some of them had freed themselves from the established Church. They cannot free themselves from progressive consumption until they free themselves from obligatory school.

We are all involved in schooling, from both the side of production and that of consumption. We are superstitiously convinced that good learning can and should be produced in us—and that we can produce it in others. Our attempt to withdraw from the concept of school will reveal the resistance we find in ourselves when we try to renounce limitless consumption and the pervasive presumption that others can be manipulated for their own good. No one is fully exempt from exploitation of others in the schooling process.

School is both the largest and the most anonymous employer of all. Indeed, the school is the best example of a new kind of enterprise, succeeding the guild, the factory, and the corporation. The multinational corporations which have dominated the economy are now being complemented, and may one day be replaced, by supernationally planned service agencies. These enterprises present their services in ways that make all men feel obliged to consume them. They are internationally standarized, redefining the value of their services periodically and everywhere at approximately the same rhythm.

“Transportation” relying on new cars and superhighways serves the same institutionally packaged need for comfort, prestige, speed, and gadgetry, whether its components are produced by the state or not. The apparatus of “medical care” defines a peculiar kind of health, whether the service is paid for by the state or by the individual. Graded promotion in order to obtain diplomas fits the student for a place on the same international pyramid of qualified manpower, no matter who directs the school.

In all these cases, employment is a hidden benefit: the driver of a private automobile, the patient who submits to hospitalization, or the pupil in the schoolroom must now be seen as part of a new class of “employees.” A liberation movement which starts in school, and yet is grounded in the awareness of teachers and pupils as simultaneously exploiters and exploited, could foreshadow the revolutionary strategies of the future; for a radical program of de-schooling could train youth in the new style of revolution needed to challenge a social system featuring obligatory “health,” “wealth,” and “security.”

The risks of a revolt against school are unforeseeable, but they are not as horrible as those of a revolution starting in any other major institution. School is not yet organized for selfprotection as effectively as a nationstate, or even a large corporation. Liberation from the grip of schools could be bloodless. The weapons of the truant officer and his allies in the courts and employment agencies might take very cruel measures against the individual offender, especially if he or she were poor, but they might turn out to be powerless against the surge of a mass movement.

School has become a social problem; it is being attacked on all sides, and citizens and their governments sponsor unconventional experiments all over the world. They resort to unusual statistical devices in order to keep faith and save face. The mood among some educators is much like the mood among Catholic bishops after the Vatican Council. The curricula of so-called “free schools” resemble the liturgies of folk and rock masses. The demands of high-school students to have a say in choosing their teachers are as strident as those of parishioners demanding to select their pastors. But the stakes for society are much higher if a significant minority loses its faith in schooling. This would not only endanger the survival of the economic order built on the coproduction of goods and demands, but equally the political order built on the nation-state into which students are delivered by the school.

Our options are clear enough. Either we continue to believe that institutionalized learning is a product which justifies unlimited investment, or we rediscover that legislation and planning and investment, if they have any place in formal education, should be used mostly to tear down the barriers that now impede opportunities for learning, which can only be a personal activity.

If we opt for more and better instruction, society will be increasingly dominated by sinister schools and totalitarian teachers. Doctors, generals, and policemen will continue to serve as secular arms for the educator. There will be no winners in this deadly game, but only exhausted frontrunners, a straining middle sector, and the mass of stragglers who must be bombed out of their fields into the rat race of urban life. Pedagogical therapists will drug their pupils more in order to teach them better, and students will drug themselves more to gain relief from the pressure of teachers and the race for certificates. Pedagogical warfare in the style of Vietnam will be increasingly justified as the only way of teaching people the value of unending progress.

Repression will be seen as a missionary effort to hasten the coming of the mechanical Messiah. More and more countries will resort to the pedagogical torture already implemented in Brazil and Greece. This pedagogical torture is not used to extract information or to satisfy the psychic needs of Hitlerian sadists. It relies on random terror to break the integrity of an entire population and make it plastic material for the teachings invented by technocrats. The totally destructive and constantly progressive nature of obligatory instruction will fulfill its ultimate logic unless we begin to liberate ourselves right now from our pedagogical hubris, our belief that man can do what God cannot, namely manipulate others for their own salvation.

Many people are just awakening to the inexorable destruction which present production trends imply for the environment, but individuals have only very limited power to change these trends. The manipulation of men and women begun in school has also reached a point of no return, and most people are still unaware of it. They still encourage school reform, as Henry Ford III proposes less poisonous automobiles.

Daniel Bell says that our epoch is characterized by an extreme disjunction between cultural and social structures, the one being devoted to apocalyptic attitudes, the other to technocratic decision making. This is certainly true for many educational reformers, who feel impelled to condemn almost everything which characterizes modern schools—and at the same time propose new schools.

In his The Structure of Scientific Revolution, Thomas Kuhn argues that such dissonance inevitably precedes the emergence of a new cognitive paradigm. The facts reported by those who observed free fall, by those who returned from the other side of the earth, and by those who used the new telescope did not fit the Ptolomaic world view. Quite suddenly, the Copernican paradigm was accepted. The dissonance which characterizes many of the young today is not so much cognitive but a matter of attitudes—a feeling about what a tolerable society cannot be like. What is surprising about this dissonance is the ability of a very large number of people to tolerate it.

The capacity to pursue incongruous goals requires an explanation. According to Max Gluckman, all societies have procedures to hide such dissonances from their members. He suggests that this is the purpose of ritual. Rituals can hide from their participants even discrepancies and conflicts between social principle and social organization. As long as an individual is not explicitly conscious of the ritual character of the process through which he was initiated to the forces which shape his cosmos, he cannot break the spell and shape a new cosmos. As long as we are not aware of the ritual through which school shapes the progressive consumer—the economy’s major resource—we cannot break the spell of this economy and shape a new one.

How may society become more aware of the ritual that now possesses it and how might learning take place if it did? I will turn to these questions in a later article.

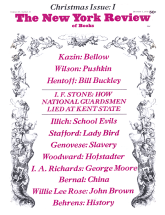

This Issue

December 3, 1970