The essays in this volume, Professor Lüthy tells us in his Preface, are all concerned with “the social order, the government of men and the paths of subversion.” They are not, he admits, arranged in any logical order and originally

…were merely scattered reflections, with back trackings, repetitions and apparent contradictions, inscribed in the margin of fifteen years of investigation of a wholly different order, through yellowed balance sheets and notaries’ jottings, in the rudely shaken human setting of French Calvinism.

(In other words the ideas, and much of the text itself, come from Professor Lüthy’s La Banque Protestante en France, published in two volumes and 1,312 pages between 1959 and 1961.) In retrospect, however, Professor Lüthy has discovered that all his reflections are variations on a theme which he describes in the Preface as “the constant placing into question of any hierarchical order in the name of an affirmation of equality that was initially a theological postulate.”

It would not be possible without a great deal of labor to discover how far the difficulty of following these and many other sentences is the fault of the translator, Salvator Attanasio, but often (and probably much more often than the present reviewer has had the patience to detect) it plainly is so. A phrase, for example, which literally translated runs: “If the peasant mass imprisoned in its customs and the tangled servitudes of its status….” emerges in Salvator Attanasio’s translation: “If the peasant mass imprisoned its customs in the tangled servitudes of its status….” “Analyse d’ensemble” is translated “concerted analysis” instead of “comprehensive analysis.” “Agricultural rent” appears as “ground rent” and “regalian rights” as “right of domain.” Worst of all certain important terms, and particularly one of Professor Lüthy’s key terms, “les parties prenantes,” are not translated at all, but left in French without explanation. Yet it would have been easy to put in a note to explain that the “prenantes” in medieval terminology were the recipients of the rents and dues of a fief, and that they constituted the class of persons whom Quesnay (in Professor Lüthy’s view the best interpreter of eighteenth-century French society) described as “useful to the State only through their consumption. Their revenues exempt them from labor; they produce nothing.” If this had been done it would at least have been possible to gain some idea of what Professor Lüthy had in mind.

After every allowance, however, has been made for the defects of the translation, and for the careless production of the book in general (in the Preface, for example, which is unsigned and undated, reference is made to Chapter XI although the book ends with Chapter X), Professor Lüthy himself cannot be absolved from the charges of carelessness and obscurity. His writing, nevertheless, is greatly to be preferred to that of many people who are more pernickety in these matters, for what he has to say can be remarkably illuminating.

He is a writer of wide knowledge and an unusual degree of insight and imagination, whose purpose is to discover the essential distinguishing characteristics of the societies with which he is concerned. He appears to have set out on his intellectual journey with questions suggested to him by the German sociologists Marx, Max Weber, and Sombart. The journey, however, has been a rambling one which he began, it would seem, in inauspicious circumstances; for the great themes he discusses in this book—the relations of capitalism and Protestantism and the nature of government and society in eighteenth-century France—are themes which he approached not by the study of any problem central to them, but by investigating a peripheral topic—the history of the Protestant bankers in France between the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the Revolution.

The belief that the only way to understand any historical situation is for a great number of scholars to start work independently at different points on the periphery increasingly governs the writing of history nowadays, particularly in France. The result—a multiplication of monographs without a comparable, or sometimes even any, increase in general understanding—is the principal subject of Professor Lüthy’s complaint against the present state of historical knowledge. He attributes this lack of general understanding, however, not to any defects of method, but to the inadequate assumptions from which historians start—assumptions which they have derived not so much from Marx himself (there can be no question, he says, “of returning to a pre-Marxian historiography or of…abandoning the exploration…of the sociological and material forces which Marx so doggedly revealed…”) as from the crude Marxism which now serves many historians as a substitute for any seriously considered hypotheses. These historians, as Professor Lüthy puts it, are “most often content to decree authoritatively a class motivation to political behavior without showing any concern for digging out the facts…which alone would enable them to demonstrate how this or that figure could have been bound up with this or that class interest.”

Advertisement

Professor Lüthy is thus a self-confessed rebel against the orthodoxy now current in France, but he nevertheless has followed the method imposed on French scholars, with results that are in one respect unfortunate. Because the subject of his research is a peripheral one, which he has pursued in great detail over many years, when he approaches the central problem he is only able to throw out suggestions. He is never able to provide the complete analyses which seem to him essential.

This has put him in a dangerous position in which he is exposed to attack or dismissal. Dismissal seems usually to have been his fate. Though La Banque Protestante en France figures in the bibliographies of most French works on the eighteenth century, no one ever refers to the conclusions. Even Professor Goubert, another rebel against the orthodoxy, accepts a large number of them, but does so in works without footnotes so that he can make no acknowledgments. Professor Lüthy, it is to be inferred, is not thought altogether respectable.

This might not, perhaps, have been surprising at a time when the historian was expected to write clearly and coherently and to repress any impulse to hasty generalizations. Now, however, that a combination of circumstances commonly force him to depart from, if not to ignore altogether, these standards of a past age, it would be unreasonable to blame Professor Lüthy because he does not always follow them. His ideas are far more worthy of attention than those usually presented to us, and he often expresses them with great brilliance and cogency.

The great merits of his writing, but also some of its defects, are apparent in the chapters concerned with the relationship between Protestantism and capitalism. In these chapters he first of all pulls to pieces Max Weber’s thesis that capitalism owed its origins to the Protestant ethic, while repudiating at the same time the Marxist thesis that the reformed religions were an expression of class interests. He then, however, concludes that, after all, the connection which Max Weber saw in fact existed, though not in the way he supposed, and that this poses a problem which needs to be examined even though historians nowadays shut their eyes to it.

Admittedly, he maintains, the Reformation cannot be said to have fostered the capitalist spirit. On the contrary, in the age of the Reformation, which was also the age of the Fuggers, it was the parts of Europe that remained Catholic that were economically the more progressive. The Reformation, nevertheless, should be seen as “the least of the obstacles to the rise of innovating capitalism.” The great obstacle was the Counter-Reformation, that “outright totalitarian reaction” against intellectual freedom. Historians, Professor Lüthy observes, have been guilty of a “fantastic error” in overlooking the importance of the Counter-Reformation in this context.

This is surely true. A great deal, for example, that is mysterious in European history in the eighteenth century might be explained if there were a good analysis of the social, educational, and political circumstances of the Counter-Reformation in the Habsburg dominions. The rise of Prussia, who triumphed over the Habsburgs in that century when all the material circumstances were against her, is unintelligible out of relation to the Enlightenment (in its German version) of which she was the center, and which began as a movement within the Protestant church. The Prussian achievement is also unintelligible out of relation to the standards imposed by the most influential of Prussia’s founding fathers, Frederick William I, who was known to his subjects as the Plusmacher because he insisted that every account should show a plus, and who was brought up in strict Calvinist principles by a Huguenot tutor.

In one passage Professor Lüthy asserts that when the Protestants became a driving force economically this was not by virtue of their Protestantism but because they were dissident minorities or refugees, inspired by a faith suitable to their circumstances. Many dissident minorities, he points out, have been reduced to sterility by persecution, or have failed, like the Catholics in England, to make any distinctive contribution to the national life. One sect of Protestants, however, the Calvinists, possessed an excellent fighting creed which equipped them, as their education similarly equipped the Jews (for both were “men of the book”), to prosper in enemy territory. The Calvinists, he quotes Sombart as saying, were “Jews without being aware of it.”

Professor Lüthy, however, does not end by ascribing the superior achievements of the Protestant states to the stultifying effects of the Counter-Reformation, or to the fertilizing influence of the Calvinist refugees, great though this undoubtedly was, particularly in Prussia. Though he insists, with many telling examples, that the degree of economic development achieved in the most progressive parts of Europe before the Reformation was nowhere surpassed until the end of the eighteenth century, he then knocks the bottom out of the conclusions to which this argument apparently leads, by saying that it was the Protestant ethic after all that was essential to the growth of capitalism.

Advertisement

In one of his most arresting chapters he points out that the teaching of the Catholic Church, even when, as in France, it was not subjected to the Counter-Reformation, was essentially hostile to the spirit of capitalism, particularly because of its attitude toward work and poverty. It separated the functions of those who worked and those who prayed and found the latter superior; poverty was holy in its eyes. “The poor man is the most beloved son of the Father…the very image of Christ…and almsgiving is the preeminent good work.”

The Reformation turned this scale of values upside down. In the new society for which it provided the ideology, begging was not meritorious but a disgrace. The duty of the virtuous to the poor was not to give them alms but to give them work. Though Calvin condemned the pursuit of wealth as such, he sanctified the qualities of industry and asceticism which naturally promoted it. In so doing his creed “simultaneously provided the pioneers and captains of industry with their impetus and justification, and habituated whole populations to the harsh discipline of work.”

It is easy to think of many cases, particularly the cases of Protestant Prussia and Catholic Austria, which support this contention. But what then becomes of Professor Lüthy’s other contentions, particularly his judgment on the Counter-Reformation? This, too, is supported by cogent evidence, but he cannot have it all ways. What does he really believe?

This is never clear. All that is clear is that he subscribes to two general propositions which he repeats on a number of occasions throughout the book. In the first he asserts that social and economic behavior is determined by religious beliefs and that these are not, as Marx maintained, merely a rationalization of class interests. In the second he asserts that the groups exercising power, or in other words the state, play an autonomous part in the working of the economy and are not, again as Marx supposed, merely the agents of the dominant social class. The essays concerned with Protestantism and capitalism are elaborations on the first of these propositions whose principal exponent Professor Lüthy finds in Max Weber. The second proposition, whose principal exponent he finds in Quesnay, provides the theme for most of the chapters on eighteenth-century France.

Professor Lüthy justly observes that the history of France between the death of Louis XIV and the Revolution presents a picture of “complete incoherence.” We have anecdotal descriptions of life in high society and accounts of apparently meaningless wars and equally meaningless political intrigues. In recent times we have also had a growing body of monographs devoted to social and economic problems. No one, however, attempts to study the “interaction between the political, economic and social sectors.” The way in which absolute monarchy functioned, the reasons for its gradual decline into impotence, the nature and sources of power of the pressure groups that brought about its downfall, are all neglected subjects.

It is this state of affairs for which Professor Lüthy attempts to sketch out the remedy, and he begins by turning to Quesnay for enlightenment. Quesnay was Madame de Pompadour’s doctor and the founder of the school of physiocrats. His most famous work, the Tableau Economique, was first published in 1758, and Professor Lüthy quotes Marx as having said that it was “the most brilliant finding ever made in political economy.” Professor Lüthy himself subscribes to this view, while nevertheless observing, in one of his ambiguous epigrams, that Marx treated Quesnay as he treated Hegel, that is, stood him on his head while professing to set him on his feet.

Professor Lüthy sees in Quesnay the author of several brilliant discoveries. He particularly stresses that Quesnay discovered the concept of the “produit net,” or surplus value, that is, to speak broadly, the surplus which is at the disposal of society after the costs of production have been met and which provides the means of civilized living. Quesnay further discovered that the state in his day caused or permitted sums larger than the produit net to be spent on consumption and war, so that it killed the goose which laid the golden eggs.

Quesnay, Professor Lüthy points out, was not so foolish as to assume that the nobles fulfilled no economic functions. On the contrary he knew that they (or, more accurately, a section of them) dominated, albeit disastrously, the two economies of France—the economy of the countryside from which they levied tribute, and that of the towns where they were the principal spenders.

In the chapter of the work here under review, “Outlines of the Age of Louis XV,” which also forms Chapter I of Volume II of La Banque Protestante en France, Professor Lüthy elaborates on these themes. The central figures in this chapter are the people he calls the parties prenantes. Admittedly it is never altogether clear to whom he means to apply the term. In general he does not use it as synonymous with the prenantes in the sense defined earlier, but commonly applies it only to a section of them, that is, to the class of persons whom contemporaries called “les grands“—the grandees—who were also the principal office-holders in the church, the fighting services, the administration, the government, and the court. These were the people who ran the state and determined the disposition of the produit net, together with further sums which in any prudently run economy would have been available for the renewal of working capital and for investment.

In this analysis there is no place for a class struggle of the kind imagined by the Marxists, which presupposed an idle and increasingly impoverished order or estate of nobility (said to constitute a social class) under attack from an increasingly prosperous and self-conscious bourgeoisie or third estate. The parties prenantes, Professor Lüthy shows, included many people of more or less recent bourgeois origin who had been weaned from their proper functions by the lure of office and its attendant wealth and titles. They cannot be equated with an order or estate. By the time of Louis XV social stratification was no longer horizontal in these terms, but vertical according to power and wealth. The only struggle that occurred was a constitutional struggle over the limits of the royal power, and it was fought out within the ranks of the parties prenantes themselves.

For anyone bent on doing so, it would not be difficult to pick holes in this analysis. In a sentence in the original text which is omitted from the translation, Professor Lüthy admits that the age of Louis XV is not the subject of his study and that he cannot analyze it in detail. His analysis is certainly incomplete. It is also sometimes misleading and often ambiguous. When, for example, it comes to whom we should describe as noblemen and whom as bourgeois (for all the more successful bourgeois acquired titles and all the great families were contaminated by bourgeois blood) Professor Lüthy is as obscure as any vulgar Marxist.

There are even occasions when he is plainly wrong, for example when his admiration for Quesnay leads him so far as to assert that all the parties prenantes derived their income from land, even when they appeared to get it from trade or finance, because the growth of trade and finance was a consequence of the rise in agricultural rents. This seems to postulate an economic impossibility. In fact, the great expansion in French foreign trade which occurred in the reign of Louis XV, but which was not accompanied by a comparable rise in domestic production, was due principally to the re-export of colonial products.

But in spite of the objections which can be brought against Professor Lüthy’s interpretation of French history in the eighteenth century, it is nevertheless by and large coherent and in accordance with the evidence, or could be brought to be so by only minor adjustments. It makes sense of a subject which has been hitherto unintelligible, and is the most plausible and illuminating analysis of the Ancien Regime in the French language.

In conclusion: whatever we may think of Professor Lüthy’s sociological propositions, for which he by no means always makes a convincing defense, and which in any case are in the nature of things unprovable, at least it must be conceded that they have provided him with a source of illumination better than any at present available to the disciples of the French orthodoxy, or to those historians in the English-speaking world who believe that they can do without sociological hypotheses altogether and that the facts speak for themselves.

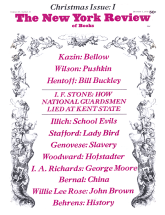

This Issue

December 3, 1970