A recent bar association report diplomatically summarized the consequences of the 1969 crime bill supported by the Administration and signed by the President:

Taken as a whole, while S. 30 demonstrates commendable effort and attention to a terribly serious problem, in its present form it contains the seeds of official repression. Some of the aspects of the system of criminal justice S. 30 would seek to impose are almost Kafkaesque: a public official could be publicly condemned on the basis of accusations of the grand jury which he had no opportunity to rebut at a trial; a grand jury witness could be imprisoned for three years for civil contempt without trial and without bail; a defendant could be prevented from raising constitutional objections to evidence introduced against him—even after having established conclusively that an unconstitutional search and seizure had taken place; and one convicted of any federal felony could be sentenced to 30 years imprisonment on the basis of “information” which could never be used against him at a trial.

Moreover, last April, The New York Times, in a series of four editorials called “The Threat to Liberty,”1 warned of “the currently evolving pattern of overt and subtle policies which tear at the fabric of a free pluralistic society.” They listed conspiracy prosecutions of dissenters, the Administration’s open exploitation of fear and discord, use of electronic eavesdropping, and “the store of computerized intelligence data banks maintained today by a host of agencies from the Justice Department to the military.”2

All this will come as no surprise to any student or victim of President Nixon’s political achievements, which include the Internal Security Act of 1950 (the Mundt-Nixon bill), passed over President Truman’s veto, a law which contains more provisions held unconstitutional3 and unworkable4 than any other statute in our history. Yet by passage of this law, even though much of it was ultimately declared unconstitutional, the authors succeeded in institutionalizing the period of repression bearing the name of a more heterodox figure, Senator Joseph McCarthy, a period that was to devastate the body politic until a new generation of young people emerged free, if not of their own problems, at least from those shibboleths which paralyzed their elders.

Justice does not deal with the incubating period of the cold war, but with some of its later manifestations. The main character is the Attorney General’s office under Ramsey Clark, in the transition period, and under John N. Mitchell. Its principal themes are the government’s control of crime, enforcement of civil rights laws, and reaction to political dissent. Most of the material first appeared in The New Yorker, for which Mr. Harris is a staff writer; hence it is a bit repetitious as that magazine’s serializations tend to be.

Obviously, Harris is too laudatory of the Justice Department under Clark, as Alexander Bickel of Yale Law School has noted with his customary sardonic disposal of enthusiastic liberals;5 for example, under Clark the bureaucracy of the Internal Security Section of the Department conducted business as usual in helping to prosecute Selective Service defectors and those accused of sedition. Yet these are minor reservations; this is a very good book which endures a second reading.

The first section of the book, “Something Has Gone Terribly Wrong in America,” begins with Nixon’s “law and order” acceptance speech in Miami, which concluded that “if we are to restore order and respect for law in this country, there’s one place we’re going to begin: We’re going to have a new Attorney General of the United States of America” (p. 14). The meretricious nature of this attack is obvious, as Harris shows: crime is essentially a state, not a federal, problem; Clark was a good Attorney General; and with changes in administration, all Attorneys General like old soldiers fade away. Furthermore, Harris quotes the candidate’s private observation: “Ramsey Clark is really a fine fellow. And he’s done a good job” (p. 15). As Mitchell said later to Clark, this attack was merely a way to “personalize” the campaign issue.

That Harris supports Nixon’s private estimate of Clark is confirmed by his impressive recital of the latter’s achievements, such as his creation of strike forces against organized crime, the concentration of drug control in a single Bureau of Narcotics, the rehabilitation of prisoners, and the training of state police. Unfortunately, these achievements did not include an interest in or ability for public relations; witness his failure to respond to Republican charges that he was “soft on crime”; note his admirable speech to state trial judges at the University of North Carolina proposing prevention of riots rather than shooting the “rioters.” While one prefers Clark’s thoughtful low-keyed observations to the hard-hat rhetoric of the present Administration, Harris makes it clear that Clark’s assistants felt that he was unwise in refusing to play the political press relations game.

Advertisement

Largely for this reason the Republicans had an almost free hand in blaming Clark for the rise in crime. They accused him of “seriously hamstringing the peace forces” (p. 54), and they attacked the Warren Court for “coddling criminals.” All of this, as Harris shows, created an atmosphere of fear among many sections of the electorate.

In appraising Clark’s performance Harris makes two interesting points. The first concerns Clark’s recent statement about the Spock case:

Under the pressure of daily business in the Department, I never had time to sit down and thoroughly sort out what I thought about conspiracy, legally speaking. I was remiss in that, I’m afraid. If I were Attorney General now, I would be inclined to prohibit the use of conspiracy charges altogether. [pp. 64-65]

This statement raises interesting questions with respect both to conspiracy law generally and to the case in which I represented Dr. Spock. It does seem strange that an undeniably thoughtful Attorney General should not have reflected upon the dangers of conspiracy prosecutions which have been so frequently noted by the courts; Learned Hand’s reference to conspiracy as “that darling of the modern prosecutor’s nursery” is by now a cliché which one hesitates to use in an appellate brief. Mr. Justice Jackson said in Krulewitch v. United States that “[t]he modern crime of conspiracy is so vague that it almost defies definition.” One also wonders whether Clark is not swinging the pendulum too far; the impropriety of conspiracy prosecution as a device for punishing public speech on public issues, which Judge Frank Coffin showed in his dissent in the Spock case,6 does not undermine the propriety of conspiracy prosecutions of organized crime under better safeguards than now exist.

Finally, the genesis of the Spock prosecution remains hidden in a political-bureaucratic nest. Clark has vigorously denied that the prosecution was instigated by the White House. I accept his word, although bitterness against former supporters was not uncharacteristic of President Johnson. Jessica Mitford in The Trial of Dr. Spock suggests that the prosecution was a compromise with Selective Service Director Hershey, who was engaging in illegal punitive action against Selective Service registrants for draft card burning and the occupation of local board offices. It seems likely that the prosecution was the result of a confluence of reaction in Congress, the Justice Department, and the Selective Service Administration to the upsurge of intellectual opposition to the war.

Harris’s second point revolves around Clark’s opposition to the anti-riot law under which the Chicago Eight were indicted, his refusal to authorize the indictment, and his conflict with Mayor Daley about law and order in Chicago, reflected ultimately in his abortive attempt to appear as a defense witness. When President Johnson, yielding to Congressional pressure, ultimately supported the passage of an anti-riot law, however, the Department of Justice followed suit in testimony before a Congressional committee.

The next major section of Harris’s book, “The Transition,” describes the transfer of power in the Department from Clark to Mitchell, who has publicly conceded Clark’s high degree of cooperation. Harris shows how the Department became a political instrument through Mitchell’s appointment of professional politicians who for the most part were insufficiently experienced and without any real understanding of the Department’s problems; and through Mitchell’s violation of his promise to confirm several judicial nominations of career men. It will be interesting to review the Department’s record at the end of this Administration in the light of the appointments made and of Mitchell’s statement to Senator Ervin that “I would hope that my activities in a political nature and of a political nature have ended with the campaign” (p. 131).

“Watch What We Do,” the title of the third section, is taken from Mitchell’s strange rebuke to blacks who complained about his civil rights program. Harris discusses the “Southern Strategy” which Barry Goldwater had attempted without success in 1964 and which was, among other things, reflected in Nixon’s nominations to the Supreme Court. A thoughtful public would be equally disturbed if it were to study his appointments to the lower federal courts, such as that of Roger Robb, the prosecutor of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Moreover, what the Southern Strategy has meant to the civil rights movement is revealed in the daily press.

Harris also describes Mitchell’s Draconian proposals for crime prevention: the modification of the Bail Reform Act of 1966 (the work of two conservative senators) so as to keep indicted persons in jail pending trial rather than to hire more court personnel and speed up trials, and the use of preventive detention, a proposal sharply criticized in another bar association report. The enactment into law on July 29, 1970, of the District of Columbia Crime Bill with, inter alia, its “no-knock” provision for breaking into homes is a major achievement of the Administration’s Justice Department. (In this connection, one must note John P. McKenzie’s conclusion that Mitchell was a follower of the “anti-crime” senators rather than a leader in the fight for crime legislation.)7 These developments confirm the warnings contained in a perceptive study of the Department by Milton Viorst in The New York Times Magazine, August 10, 1969, to whom Mitchell explained that, unlike Clark, he believed that the Department “is an institution for law enforcement, not social improvement.”

Advertisement

More recently, the Department has manipulated grand juries in a manner developed decades ago by Assistant United States Attorney Roy Cohn and his Democratic colleagues in the Southern District of New York. In this connection, it is worth recalling the opinions of two of the country’s best judges during that period upholding the principle that grand juries must not be used as the government’s political tool: Chief Justice Learned Hand’s dissent in the Remington case,8 where the grand jury foreman had a business arrangement with Elizabeth Bentley, the prosecution’s star witness; and District Judge Edward Weinfeld’s opinion in Application of Electrical Radio and Machine Workers of America,9 which held illegal a grand jury presentment accusing union officials of false Taft-Hartley affidavits. Harris recounts Mitchell’s recent grand jury subpoenas to secure the names of persons responding to a New York Times advertisement for public support for Eldridge Cleaver’s case.

Since then, the Department, in its drive against the Black Panthers, has sought to examine reporters’ private notes, particularly those of Earl Caldwell of the Times, and has incited state police raids against that group. It has secured federal felony indictments for insignificant offenses against state law, and its abuse of student dissenters has created the very polarization which it claims to deplore. The White House’s angry and incredulous reaction to the report of its own investigator, Chancellor Alexander Heard of Vanderbilt University, that the Indochinese war is a major factor in student unrest is a case in point. Still, as I.F. Stone notes, it is standard practice for governments to appoint commissions and to disregard their reports.

While vigorously prosecuting minority and dissenting groups, the Department has made a shambles of the civil rights program. No one I’ve read has described better than Harris the Administration’s meneuvering on school desegregation, busing, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (see pages 194-216), which resulted both in a revolt by Health, Education, and Welfare and Justice Department employees and the recent spectacular Supreme Court decisions against the Department on integration. The recent public attack by the relatively conservative NAACP upon the Administration serves to underscore Mr. Harris’s account.

The Department’s political flavor reminds me of President Harding’s cabinet (including Attorney General Daugherty)—although certainly there is no suggestion of corruption today, in spite of the present Cabinet’s ties with the business community. “The rest of the Cabinet, except Hughes and Hays,” wrote William Allen White in his Autobiography, “were for the most part starched shirt-fronts, human bass drums, who boomed out in front of the plutocratic stage-show with bellowing banners, shouting the wonders of the fat boy of prosperity and the octopus of big business and the fire eater and sword swallower of a starved but greedy militarism.”

Today the Department is managed by a group of political figures (Mitchell, of course, is a newcomer to politics) driven by the success of their campaign strategy to try to repeat their television slogans in office: as fast a retreat on civil rights and as vigorous an attack upon dissent (student, television, and university) as seem feasible, interwoven with as heartless a program of criminal law enforcement as can be carried through the Congress and the courts.

The Nixon Administration is not the first to confuse politics with law. Robert Kennedy, too, was a campaign manager who became Attorney General, and his legal experience for that post was as insubstantial as that of Mitchell. Indeed many, like this reviewer, will find legal expertise in municipal bonds a more palatable qualification than that of having been a minority counsel to the McCarthy Committee. Nor do I find persuasive the justification by Robert Kennedy’s supporters for his approval of the wire tapping of Dr. Martin Luther King—or anyone else. Kennedy, however, had more qualified assistants and more concern for the poor; and he enforced the civil rights laws.

Nevertheless, the administration of justice would be advanced if campaign managers did not become Attorneys General and if the latter avoided participation in White House politics. Since we are on the subject of improvement of justice, I might add two other bad practices which should be eliminated: close relationships between the President and justices of the Supreme Court and the assumption of extrajudicial functions by the latter. It is absurd to regard such judges as indispensable (except to the business of judging) or to expect true judicial independence from entangling alliances with the President. How could even as good a justice as Abe Fortas (I charitably pass over his vulnerable essay, “Concerning Dissent and Civil Disobedience”), be a Presidential adviser on Vietnam during his brief tenure and also adjudicate legal issues arising out of that war?

The greatest danger to our democratic system lies in the power of the Chief Executive, which neither Congress nor the courts have for the most part demonstrated the ability or a genuine desire to check.10 The danger is increased by the power of the military establishment, technically under the control of the Commander-in-Chief, as Robert Heilbroner recently described in these pages.11 The courts have protected our constitutional liberties during the worst years of the cold war in many if not all areas, largely because of Black and Douglas, two Roosevelt appointees, and two fine Eisenhower appointees, Warren and Brennan. It may not be possible to turn the constitutional clock too far back, yet the President possesses the awesome power to remake constitutional law by his judicial appointments on all levels. President Kennedy made some poor appointments particularly to the Southern federal district courts (such as Judge Cox of Mississippi), which stalled the integration program. President Johnson manipulated the Supreme Court when he replaced Goldberg with Fortas and then tried to move the latter into Chief Justice Warren’s seat, which then delayed his appointment of a new group of liberal justices until it was too late, a misuse of Presidential power for which we shall dearly pay the price.

President Nixon’s recent handling of Supreme Court appointments left the Court with eight justices for more than a term; the result is an unprecedented number of rearguments during the last and next terms. A most important question is whether the Senate will have sufficient interest, patience, and resilience to carefully scrutinize the nomination of several hundred judges who will be appointed by President Nixon, particularly since some of them will be without prior judicial records to scrutinize. The American Bar Association has been guilty of gross neglect in approving nominations of persons incompetent to hold high judicial office, as witness Circuit Judge Harold Carswell’s demeaning campaign for the Senate. This behavior of the Association is consistent with its support during the cold war period of a red hunt among lawyers as well as among applicants for admission to the Bar; it has shown no embarrassment on either occasion. We must therefore depend for information concerning Nixon’s judicial nominees upon law school faculties and students and upon civil rights organizations.

The danger of a Nixon Court reminds us once again of the fragility of total dependence upon the judicial branch for the protection of constitutional rights. The advanced ages of the liberals, Black and Douglas, and of an enlightened conservative, Harlan, mean that a Court worse than that of Chief Justice Vinson may be with us again. Such a Court would be increasingly unwilling even to review lower court decisions posing important questions of federal and constitutional law. And if review is granted, such a Court would probably uphold, although by divided vote, legislation restricting minority party participation in electoral politics, crime legislation, state sedition laws, and investigative, police, and criminal procedures which the Warren Court would have stricken. In view of the close votes expected from the present Court, a further shift can only be in the wrong direction.

The truth, which the Administration conceals now as carefully as it did during the election campaign, is that the states, not the federal government, have the principal responsibility for the prevention of crime. But crime prevention will not be achieved by more legislation or by a shift from Supreme Court decisions protecting individual liberty. The state system of criminal justice cannot be improved so long as policemen are underpaid, uneducated, collaborate with narcotics pushers, commit perjury, use agents provocateurs, and are permitted and even encouraged to shoot civilians; even civilians attempting to avoid arrest are, after all, entitled to live. The tendency of the police to commit homicide was recently reflected in the Memphis Safety Director’s approving statement that “as long as that gun is on the hip of a policeman, it’s there for killing.”12

What shall we say of a system in which grand juries rarely represent a cross section of the community, where prosecutors use lists of “subversive” associations and are permitted to select the judges for particular cases (as in the New York Panther trial), and where so many judges are chosen from the prosecutorial ranks. These are the realities of the criminal law—known to every lawyer—and concern about none of them is reflected in the Administration’s crime program.

While criminal justice is a state matter, it can be influenced by the behavior of the federal government. Hence it is significant that the Administration’s policies, domestic and foreign, are creating chaos in the country, vide Cambodia and Kent, which results in repressive measures leading to further chaos. The Administration also controls the federal legal machinery; appoints the United States Attorneys; creates and effectively commands an army, despite the many who resist induction and the lesser number who, after induction, try to democratize the military. The federal government furnishes a terrible example to local governments which have to meet the “crime wave” it has created. The federal government also pollutes the social atmosphere by its continuation of the war which makes violence an integral and sometimes inevitable part of our social organism. In this context, talk of law and order is ludicrous.

It is no wonder that Harris concludes that “[m]ost people no longer seem to care—if indeed they know—what is happening to their country” and “[w]hen the people finally awaken, they may find their freedoms gone, because the abandonment of the rule of law must bring on tyranny.” I second his warning with these qualifications: this country has shown itself capable of surviving earlier periods of repression—those of the Alien and Sedition laws, those of the Palmer raids and of the McCarthy period, although in the last of these the Administration in office was not the leader of the forces of repression. While the present Administration is more threatening to civil liberties than any other in recent history, that very threat has created an opposition not only among prominent people but in large sections of the public. The horror at what we are doing in Indochina should make it impossible to resell the Joseph McCarthy script.

Yet, as Professor Thomas I. Emerson recently noted in a review of Justice in the Nation, there is a fundamental problem with which Harris does not deal: the existence, regardless of the Administration, of a different law for the rich and the poor, the whites and the blacks. If the youth of today have one clear insight, it is into that truth.

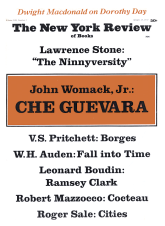

This Issue

January 28, 1971

-

1

The New York Times, April 27-30, 1970, editorial page.

↩ -

2

The breadth of the last enterprise was recently described by Ben Franklin, one of The New York Times‘ best-informed reporters, June 28, 1970.

↩ -

3

See, e.g., Brown v. United States, 381 U.S. 437 (trade union office); Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (passports); Robel v. United States, 389 U.S. 258 (defense employment).

↩ -

4

See Communist Party v. United States, 331 F. 2d 807, cert. denied, 377 U.S. 968.

↩ -

5

See Bickel, “The Good Guys Forever,” The New Republic, April 18, 1970, p. 21; cf. the enthusiastic review of Professor W. Carey McWilliams in The New York Times Book Review, March 22, 1970, p. 7 et seq.

↩ -

6

United States v. Spock, 416 F. 2d. 165.

↩ -

7

Review of Harris, Justice, Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review, April, 1970, p. 522. McKenzie, a most informed reporter, makes many other important points in his review, which I recommend to the reader.

↩ -

8

United States v. Remington, 208 F. 2d 567, cert. denied, 347 U.S. 913. Remington’s first conviction had been reversed, 191 F. 2d 246; the Supreme Court declined to dismiss the indictment, denying certiorari, 343 U.S. 907.

↩ -

9

Application of United Electrical, Radio & Machine Workers, 111 F. Supp. 859.

↩ -

10

See e.g., Senator Stuart Symington’s devastating “Congress’s Right to Know,” The New York Times Magazine, August 9, 1970.

↩ -

11

“How the Pentagon Rules Us,” The New York Review, July 23, 1970.

↩ -

12

The New York Times, July 6, 1970, p. 34.

↩