In response to:

Three Who Didn't Make a Revolution from the January 7, 1971 issue

To the Editors:

Murray Kempton’s hatchet job on Tom Hayden [NYR, January 7] cannot be suffered in silence. From all appearances, it was an act of pure malice, lacking even the justification that Mr. Kempton had a particular political axe to grind. But for someone so proudly independent of party loyalty as Mr. Kempton, the effort is oddly loaded with distortion and deceit.

Even a brief comparison between the actual text and Kempton’s report of it reveals that Kempton has chosen to misrepresent virtually every selection from Hayden’s book with which he deals. For instance, Tom Hayden is accused of being an opportunist, in search of “votes” and constituents, presumably without reference to any coherent principles or values. The only evidence Kempton provides to support this view is that Hayden now welcomes homosexuals to the movement, whereas only a few months earlier he was not above questioning the unconscious sexual preferences of prosecutor Foran.

Leaving aside the fact that Hayden was not offering his own diagnosis of the prosecutor, but instead repeating a quip attributed to Stew Albert, the entire point of Hayden’s depiction of Foran was that he “represented the conventional image of manhood to the jury—a fighter, father of six, earthy but intelligent, still vaguely handsome, knowledgeable in the ways of the world, but struggling as a Catholic to retain purity” (Trial, p. 53). The entire passage, as well as the one on sexual attitudes of police also cited by Kempton, can hardly be read as a scurrilous invasion of privacy offensive to homosexuals; on the contrary, they represent critiques of conventional masculine poses and stereotypes—critiques which would be entirely consistent with Hayden’s recent expressions of alliance with the Gay Liberation Front. Oddly, Kempton not only quotes out of context, but neglects to recall to readers the widely reported attack by Mr. Foran on Allen Ginsberg and on the Chicago Seven and their “fag revolution.”

Tom Hayden’s cold calculation is alleged to be manifested not only in his cynical manipulation of “voting blocs,” but equally in his alleged callous desire to utilize the fate of Bobby Seale for his own ideological ends. Kempton charges that Hayden wishes the Panthers and their white defenders to ignore the specific facts of the New Haven case, and goes on to show that Hayden was particularly scrupulous to present the “reality” rather than the “fantasy” of his case when he himself was in the dock.

Readers interested in Hayden’s actual views should turn to the book itself. There, in Chapter XIV, one finds a rather subtle argument about the relationship between white radicals and black revolutionaries, an argument which pivots on the painful reality that whites and blacks are inextricably interdependent and yet have separate interests which conflict, that the Panthers, at great costs to themselves, have tried to accept that interdependence even as they were aware of the ways in which racism and privilege damaged the capacity of whites to be effective allies. What Hayden suggests in that chapter is that white radicals adopt an attitude toward the Panthers comparable to the one they have taken toward the NLF—to defend the Panthers not simply as victims, but rather as the leading element in the struggle of the “black colony” for self-determination. At no point does Hayden urge the Panthers or their supporters to ignore the facts in their legal defense; instead he urges on white radicals that their view of the “facts” not divert them from a more comprehensive campaign to “withdraw the troops” from the black colony as well as from Vietnam.

Now it is Mr. Kempton’s right, and even duty, to question this analysis in terms of its political utility. Indeed, Kempton’s extended argument about the New Haven affair appears to have considerable wisdom—but is not necessarily contradictory to the position taken by Hayden. But, Kempton chooses not to debate Hayden’s political perspective so much as to distort that perspective in order to impugn his motives. Further, one would not know from Kempton’s review that Hayden devotes an entire chapter to “thoughts on political trials” in which he tries to synthesize the need to present an effective legal defense with the need to utilize the trial to support the political objectives of the defendants. He would rather depict Hayden as a man insensitive to the painful dilemmas, and self-serving to boot.

Next, Tom Hayden’s opportunism is alleged to be revealed by his unconscious vacillation between “liberal” ameliorism and “revolutionary” postures of total condemnation. Such incoherence is supposed to be manifested in Hayden’s analysis of Judge Hoffman and of police attacks on demonstrators. That Hayden’s discussion of Hoffman was entirely devoted to an effort to demonstrate that the judge’s apparent eccentricities were representative of his “class,” and that the judge was a necessary element of the system of government of the city of Chicago (and of the US as a whole)—one would never guess from Kempton’s discussion. As for the police—the reader should compare what Kempton claims Hayden doesn’t say with what Hayden says—the reader will find an astonishing similarity between the two passages.

There are still other examples of apparently willful misrepresentation of Hayden’s expressed views, and of grotesquely uncharitable interpretations of his intentions. But beyond the distortion is the fact that Kempton chose to dismiss all of Hayden’s political proposals and recommendations as “fantasy.” Since the burden of the book was not to discuss the Trial in Chicago, but the problems confronting the Movement in the seventies, and since that question is one which surely interests N.Y. Review readers a good deal more than Mr. Kempton’s tastes in revolutionary style, it’s too bad readers were not informed that Hayden’s book contains his views concerning black-white relations in the movement, the problem of repression, the antiwar movement, male domination of the movement, the relation between radical politics and youth culture, and the political significance of the emerging “youth ghettos,” among other issues.

Surely, if Mr. Kempton believes Hayden’s comments on these matters partake largely of “fantasy,” he is under some obligation to argue that point. Readers will find much which is inadequate and worthy of dispute in Hayden’s writing—but they are also likely to find that it has quite direct bearing on the present realities experienced by radical activists.

A final point about this book. It does have an impersonal tone—if Mr. Kempton was hoping for something else, perhaps he has cause to feel disappointment. But, according to Kempton, there is only one “personal” sentence in the volume, and that, according to Kempton, was an “aside.” Perhaps nothing more reveals Kempton’s incapacity to review this book than that observation. The sentence he quotes is imbedded in a chapter called the “Limits of the Conspiracy”—a chapter whose entire point was to confess the inadequacy of the style of leadership which Hayden and other members of the conspiracy had adopted—and to advocate its end. Nothing could be clearer than that Hayden, in this chapter, is painfully self-critical, self-consciously rejecting the demagogic, opportunistic leadership posture which Kempton accuses him of now adopting.

How well does Kempton’s portrait of Hayden stand up against passages like this: “We are just the kind of individualists around whom a movement should not be consolidated. We are valuable perhaps as a resource to draw upon, but not as a leadership to unite behind. Our power interests and our male chauvinism would be a drag on the growth of revolutionary energy…. One of the most revolutionary decisions possible is for leadership to refuse to consolidate its own power and to choose instead to follow new vanguards” (p. 111, 113).

Now Kempton is right in this: Trial is less a book than a pamphlet, less a memoir than a manifesto, less an analysis than a sermon. Against pamphleteering, Kempton argues for the “revolutionary duty to describe,” and expresses the need for persons who can be believed. If these are duties, as Mr. Kempton emphasizes, why has he not done his in this instance? He is a journalist (and ever since my high-school days I have thought him one of our greatest) and yet he chooses to write about Tom Hayden as would a literary critic. His duty, if he wished to be serious about description and about his craft, was to study the man in the flesh, to interview him (Tom, he says, never talked to a policeman, but Murray—has he ever talked to Tom?), to observe him in action, to talk to his actual comrades (who actually do exist).

If there is anything to be said about Tom Hayden and the sources of his hurts and warts, etc., it is that he is doing his duty. That is perhaps why he is so offensive to Mr. Kempton’s “us.” “We” would like to be satisfied with incisive criticism, brilliant insight, verbal honesty, and eloquent charity to those who are more lost and strung-out than “we.” “We” even enjoy a bit of marching now and then. The trouble with Tom and a lot of those kids is that they want to keep on marching. Not only is that pretty damaging to “our” sensibilities, but “we” aren’t even sure where the march is going. “We” would prefer that Tom got off the line and joined “us” on the sidelines—much prefer that to joining the march and helping define its direction. It’s all so unattractive, anyway.

Richard Flacks

University of California

Santa Barbara, California

Murray Kempton replies:

Professor Flacks’s reproach should be permitted to run at the length it requires; and there is little use in my intruding upon his space. That does not mean that he has in any way altered the feelings which Trial evoked in me and which I had certainly hoped were more pained than malicious. I am, to leave the matter with one minor point, somewhat puzzled to find that Professor Flacks counts it a piece of moral obtuseness in me that I did not regard Tom Foran’s having called Tom Hayden a fag as making it entirely proper for Hayden then to suggest that Foran might be a fag.

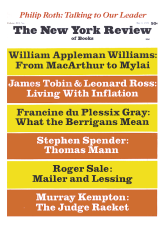

This Issue

May 6, 1971