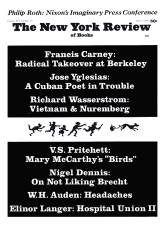

On the eve of the Berkeley municipal elections on April 6, Ronald Reagan and other conservative spokesmen in California officially lamented and denounced what they called “an impending radical takeover” in that volatile city. As soon as the election was over and before its somewhat ambiguous results could be analyzed, it was the turn of the liberal newspapers and television stations. They spoke in tones of accommodation. The San Francisco Chronicle and the Los Angeles Times were gratified because the election had demonstrated that it was possible for the alienated to “work within the system.” The New York Times confidently called the results “another defeat for extremism” and claimed that “the middle of the political spectrum, where almost all elections are decided, was moved to the left.”

Well, the event scarcely ranks in the annals of revolution alongside the formation of the Paris Commune, but neither was it simply a victory for some dynamic young liberals and urban reformers. It was much more than that. If it was not in every respect a great radical victory it was a victory for radicals. The partial victory of the Berkeley radicals, moreover, has meaning beyond the boost it gives to the morale of the American left in the age of Nixon and in the land of Reagan.

On the surface, the victory lay in the election to the City Council of three out of a slate of four young radicals running under the aegis of a diverse group of students, intellectuals, and white radicals called the April Coalition, and in the election of a militant young black councilman, not technically a part of the radical slate, to the office of Mayor. Warren Widener, the Mayor-elect, is a friend and protégé of Ron Dellums, surely the only member of the US House of Representatives who might plausibly be called “radical.” Widener will vote with the three new radical Council members on most of the important issues.

Right now, the crucial question is who will fill Widener’s vacated seat on the Council. There is strong pressure from the left, and a surprising amount of acquiescence from the center, to fill the seat with a fourth member of the radical slate, Rick Brown, a young graduate student in education, who lost the election barely. If Brown is appointed, the four April Coalition radicals and Widener will constitute a majority of the Council (eight members in addition to the Mayor). There is, of course, pressure not to appoint Brown, to appoint instead a “swing” member as a compromise. But there is almost no way that the seat can go to an appointee wholly unacceptable to the Coalition and to Widener. There is every prospect, then, for a radical majority on many issues. That is one, minimal meaning of the election.

Community Control of Police

What comforts the establishment, aside from the fact that all of the radical winners are young, personable, articulate, deadly serious, and clearly well-informed on matters of municipal governance, thus, presumably, assimilable or, at least, amenable to reason and experience, is the decisive defeat in the election of the much publicized proposal for “Community Control of Police.”

That proposal, in the form of an initiative charter amendment, is not well understood outside of Berkeley, though it was certainly well enough understood by the voters of Berkeley. That it was a radical proposal cannot be doubted. There is a false impression that the Community Control proposal was originated by the blacks. It is rumored that the rough idea for the plan came from Bobby Seale, who then handed it to several lawyers to “work up” for placement on the municipal ballot. Actually, the sponsoring and organizing group was called The National Committee to Combat Fascism, a coalition of left-of-center groups which are mostly white but which include the Black Panthers. The Community Control plan itself was apparently drawn up by two lawyers, Peter Frank and Gordon Gaines, working for NCCF out of the Black Panther Party national office. About a year ago NCCF began to circulate throughout Berkeley a petition to put the Community Control plan on the ballot for 1971.

In the spring of 1970, of course, the city was in convulsion. In April there were numerous trashings on the Berkeley campus and two full days of what amounted to pitched battle between the familiar alliance of university students, high-school kids, and street people on one side and massed police from several jurisdictions on the other. In May, after the invasion of Cambodia and the massacres at Kent State and Jackson State, a prolonged and complicated “reconstitution” crisis developed. From early May until the end of the school year the streets of the city swarmed with hundreds, perhaps thousands, of young people looking to “do something,” that is, to do some political work.

Many were able to work in Dellums’s campaign for the Democratic congressional nomination. Others worked for Ken Meade, a young liberal seeking the Democratic state assembly nomination. Others helped NCCF to circulate the Community Control petition. It was an exhilarating time for young Berkeley radicals, and in such an atmosphere signatures on the petition came easily. By July NCCF had more than twice the 8,000 signatures needed to qualify the proposal as a charter amendment for the 1971 ballot. It was subsequently adopted by the April Coalition as part of its platform. It was a fateful and possibly a Pyrrhic triumph.

Advertisement

That the Community Control of Police plan engaged the deepest and most powerful political passions of one segment of the Berkeley left cannot be doubted. Tom Hayden, who drove himself hard in the campaign for signatures just as he was to drive himself hard for the amendment during the election campaign, said at the time, “This plan is the last chance of those who say they want peaceful change….” But by no means all of the Berkeley left was so committed to that particular plan for community control of the police. As even a glance at the plan itself will show, it was a strike at the vitals of that institution which is the prized symbol of the urban middle class, the police.

The Community Control of Police amendment would have abolished the unified Berkeley Police Department and created in its place three separate and autonomous departments called Neighborhood Divisions, one for each of three major sections of the city. The Neighborhood Divisions would reflect the regions of Berkeley: the western flatlands in which live most of the city’s black population as well as a substantial and diverse number of nonblacks; a sprawling prosperous “white” section including the Berkeley hills where lives the Berkeley gentry, including the mandarins of the university faculty and administration; and a small, densely populated section immediately south of the campus with Telegraph Avenue as its axis, largely inhabited by students but also by university-oriented intellectuals and professionals outside the gentry, hippies, “street people,” commune dwellers, drug culturists, assorted freaks, a few funky old people, and even some conventional citizens.

The “south campus” is the heart of the Berkeley Scene. People’s Park is there and so are the “dorms,” the crash pads, the head shops, the movie houses, the bookstores, the coffee-houses, and the sidewalk artisans. In fact, the whole colorful Berkeley imbroglio is there, with its seemingly shambling and disorderly movement of people. Sometimes they call themselves freaks. More often they call themselves “the people.” Reagan looks down at them from Sacramento and thinks that they are denizens of some wicked, unspeakable place, that one day they will come swarming up out of their filth and horror to destroy—what? The State. Order. Civilization itself.

The middle-class Angeleno, suntanned, bathed, and scented inside his jersey jumpsuit, turns on the six o’clock news and views the latest events in Berkeley. He sees those frail, bearded young men, those strutting, outrageously garbed blacks, those sturdy long-haired young women, braless in T-shirts. “They are making new demands on the administration,” he is told by the announcer. “They are shouting obscenities at the police.” The middle-class Californian likes the Berkeley “people” no more than Reagan does. “Technology Sucks! Off the Pig! Off the State! Fuck Authority!” Their message sounds to him hateful and inexplicable.

Yet the Berkeley election of 1971 in some way belongs to the freaks, to the people of the south campus area, as much as it belongs to anyone, even to the older, more sober radicals of the April Coalition. In the end, community control of police was their issue more than it was the blacks’. The students and freaks and street people are a constituency. They have entered normal politics in a tentative way and one cannot say with confidence just what that means, or how long it will last.

To establish community control of the police, then, the amendment would have given control over police policy in each of the three areas to Police Councils elected by the voters from Police Council Precincts. There would have been two councils of fifteen members each in the black area and white area respectively, and one council in the campus area. The councils would choose individual commissioners to carry out day-to-day administration of each police department, but policy would remain with the councils. In addition the amendment provided for easy recall of either councilmen or commissioners, called for grievance procedures to be maintained by the councilmen, and required frequent public meetings for commissioners and councilmen, to be held “at a time when interested persons may attend.” Finally, the amendment required that all police officers must live inside the area served by his or her department. (At present all but thirty-five of Berkeley’s 200 police officers live outside the city.)

Advertisement

Under the amendment, the police budget would still have been appropriated by the City Council but would have been disbursed to the three departments according to population, thus ending the City Manager’s control of the police budget and putting it, in effect, into the hands of the voters. The tendency of the amendment, plainly, was away from professionalism, from managerialism, and from police autonomy, and toward community participation in police affairs. As Tom Hayden wrote in the amendment’s defense, “[It] goes beyond the philosophy of representative government and suggests the solution of direct democracy.”

As it turned out, no one but the students and the freaks really wanted the Community Control amendment. The proposal was defeated by a two to one majority. Of the 160 precincts, it carried only twenty-eight, of which all but five were in the campus area. The amendment carried no predominantly black precinct. In fact, most of the black precincts also voted against the amendment two to one. Congressman Dellums, it must be remembered, strongly supported the amendment, though he did not campaign for it as diligently as he campaigned for the election of Warren Widener and the four members of the April Coalition council slate.

The April Coalition was powerfully committed to the amendment and both white slate members campaigned hard for its adoption. The Black Panther Party supported the amendment and was supposed to be campaigning for it throughout the black community. The Black Caucus, an umbrella group which was part of the April Coalition, supported the amendment. Widener himself did not endorse the amendment, but made it clear that he supported its principles.

But, clearly, any belief that measures for community control, even community control of police, automatically command black support is confounded by these election results. Confounded too are easy assumptions about a “natural” alliance between blacks and young white radicals and students. The black community certainly contributed to the election of the three April Coalition radicals, mainly to the victories of the two young black lawyers on the Coalition slate. But, again, the election returns clearly show that Widener did not carry the black community. In the heavily black precincts, he was decisively beaten by his principal opponent, the liberal Democrat Wilmont Sweeney, the first black to be elected to the Berkeley City Council and a vehement foe of community control of the police.

Widener’s hairline margin over Sweeney is due entirely to the huge pluralities he rolled up in the campus area. After one has made allowances for the fact that Berkeley is not Newark or Harlem or Watts, that its black community is not a dense, groaning mass but a mixed community of poverty-line people, white and blue-collar workers, and a good many middle-class artisans, proprietors, and professionals, one must still be struck by the divergences between the vote of the blacks and the vote of the students, intellectuals, and white radicals who comprised the main force of the April Coalition.

Those divergences raise questions not only of what was won and what was lost in Berkeley, but also about the general potential of a radical coalition of students, older intellectuals and professionals, and blacks. Equally important is the question raised about “cultural revolution” as opposed to radical politics. To raise the last question is not to prejudge the answer. The wildest freak who went out and did his bit for the Community Control amendment was doing political work. He was at least seeking to legitimate the authority of the police. He was also seeking to educate a community, and he may have been seeking to win political power in the city.

The community control measure itself, while it may appear to be an attack on the cops or a bizarre attempt to get the police off the backs of the blacks, students, and street people, did contain genuinely political elements. So did much of the rest of the April Coalition platform. But it is not clear that the students and the street people, who played such a large role in the election itself, are committed to a coalition with the blacks and the working class, or that they are committed to any long-run political strategy at all. To look more closely at these questions, it is necessary to look at the April Coalition and its platform and campaign strategy.

The April Coalition and Electoral Politics

Berkeley, as nearly everyone knows, is not an ordinary university town. It is a handsome city of 113,000 citizens, of whom around 30 percent are black. Its climate is probably as fair as this planet can offer, seeming to the easterner languorous and to the southern Californian bracing. It is a very hard place to leave for those scores of the university’s newly minted PhDs who literally have to be driven out each year into the provinces (New York, Cambridge, southern California). It isn’t just the climate and the bay and the hills and the flowers, or the intellectual and political excitement in and around the university. All of these things combine to help make the city a marvelous place to live and work in.

There are, to be sure, plenty of weeds and even serpents in the garden. The black third of the population is lively, aggressive, upwardly mobile, and sharply separated geographically. The south campus area has been turning increasingly ugly as the dope trade, street crime, overcrowding, and years of struggle with the cops have altered its character. In Berkeley, as elsewhere, the symptoms of contemporary urban pathology have made their unmistakable appearance. The demand for public services has been increasingly insistent but the city already has one of the highest municipal tax rates in the nation.

The university, which pays no taxes, gobbles up larger and larger chunks of income-producing land, meanwhile attracting to itself a large population demanding services. The students and the street people feel themselves to be members of the community but, at least so far, powerless to affect its life. The older residents, the middle classes, and the straights groan under the tax burden while simultaneously fearing that their beautiful city is turning into Haight-Ashbury or Sodom. The university, preoccupied with its own internal problems, insists that it cannot solve them until the community around it has been brought under control. The blacks, while not lacking formal power these last half-dozen years, find it difficult to turn representation into jobs, housing, medical services, and status.

Berkeley has for decades been known as one of the best governed cities in California. When Californians say best governed, they usually mean well administered. When they say well administered, they usually mean professionally managed. Berkeley has been professionally managed, by a succession of recognized experts, since 1924. It lives under the “strong manager” system. The City Manager controls the budget and appoints heads of departments, all of whom are responsible to him, and heads the municipal civil service. The Council and Mayor are nonpartisan, as in all California local governments, and weak with respect to the Manager. The members of the Council are elected at large in “oneshot” elections, four of the eight Council members being chosen every two years.

The watchwords here are efficiency, professionalism, and administration over politics. The Berkeley Police Department has been celebrated for decades for its professionalism, its high standards for officers, its ties to the university’s School of Criminology, and its freedom from both corruption and “politics.” The city’s civil service is highly professional, free of corruption, and, by all of the orthodox criteria, competent. Berkeley municipal government thus combines cool, professional management and an efficiently bureaucratized civil service with a politics of low visibility. All of this was attacked by the April Coalition, which sought to raise politics over administration and to radically hand government over to the neighborhoods and communities.

Berkeley has always been a “progressive” city. A few years ago it swiftly integrated its school system. In this effort a smoothly functioning city government and school system were highly effective, keeping strife at a minimum. The program has worked well: It is a model for any other geographically segregated city and Berkeleyans are justly proud of it. The success of school integration, surely, was a major factor in the black community’s decisive rejection of community control of the police.

In spite of the tensions of generational and communal strife, Berkeley is a tolerant city. While studying this election, I talked with a man in his late twenties who lives in a smallish flatlands commune and who had done much organizational work in his neighborhood for the April Coalition. He mentioned that several children lived in the commune, and I asked him if the kids were hassled very much over the arrangement by teachers and principals at school. He smiled and said, “No, this is Berkeley. Anywhere else we might get hassled, but here the school authorities accept our arrangements as natural enough.” Berkeley is also a Democratic stronghold in party elections. It helps to send liberal Democrats to Congress, and in 1970 it provided the base for the smashing victories of the radical Democrat Dellums.

But Berkeley has not been a radical city. Until this year, it seemed unimaginable that a group of unknowns calling themselves radicals and running on an indisputably and wildly radical platform could have become the most formidable power bloc in the city government. For the April Coalition to achieve the success it did, everything had to fall into place. None of the three successful Coalition candidates even came close to winning a majority of the votes. Their victory was not a case of a desperate and radicalized community turning to its natural leadership, but of excellent organization, of alliances and skillful electioneering, and, perhaps most important, the intense mobilization of students during the campaign and on election day.

In one sense, it was the Community Control of Police amendment that galvanized the students and street people who provided the victory margins for the three April Coalition winners and Widener. On the other hand, the police control amendment clearly alienated much of the black community, diminished their support for some of the April Coalition candidates, and led to the entry into the Council race of several candidates who drew off black support from the Coalition. I am even tempted to say that the Community Control amendment cost the radical coalition outright control of the Berkeley city government.

The drive to win power for radicals in Berkeley began long before the Community Control of Police amendment qualified for the ballot. The essential components of the April Coalition had already been assembled a year before in Dellums’s campaign to unseat the liberal Democratic 7th Congressional District incumbent, Jeffrey Cohelan. There are roots of it in the Committee for New Politics formed in the aftermath of the campaign of Robert Scheer for senator in 1966, and even in the split of the Democratic Club Movement over the Vietnam war in the same year. Berkeley has always been home for many radicals, old CPers, old Trotskyists, socialists, independent radicals, and left-wing Democrats. Their number, moreover, has always included radical faculty members and “hill” dwellers with skills, money, and organizational experience.

These older leftists, liberals, and radicals have no prejudice against working in elections, seeking office, cooperating with Democrats, and, when necessary, acting pragmatically, even opportunistically. They can view public office as valuable in itself, can conceive of an election campaign as a process of public education, and do not believe that electoral campaigning and buïlding a radical movement are irreconcilable. This is not to say that they are running dogs of the Democratic Party, or “old whores” as some young revolutionaries are inclined to call them. They were, after all, prepared to try the impossible in the Scheer campaign and in 1970 set to work as soon as the formidable Dellums came into view. They see themselves as keenly conscious of the movement and are sensitive to the need for coalition with the blacks in the East Bay. They do not, typically, make any distinction at all between electoral politics and a presumed “real” politics.

Younger radicals and movement people who can still be called New Left, on the other hand, speak of “electoral politics” nearly always with contempt. “Oh, you’re talking about electoral politics. Well, if that’s your bag….” Such contempt implies that there is another politics, a real politics worth a serious radical’s time. Real politics are participatory, in this view. Real politics are joining with others to take concrete actions that materially affect one’s own life and the general interest of the community. This means confronting officialdoms, organizing communities, formulating demands, debating values, goals, and tactics, possibly demonstrating and bearing witness, sometimes resisting law and constituted authority. The overwhelming symbol of the American electoral process is the solitary voter, isolated in his curtained polling booth. Can politics be so important if that’s all there is? Can the social scientists be serious when they call that participation? Can the voice of the people be no more than the sum of the ballot markings of those isolated individual voters?

A very young Berkeley radical may not have read Hannah Arendt, but there is a clear suggestion of Miss Arendt’s ideas in the view that politics is action centered around the vital institutions of a community and that such action is not only the heartbeat of community life, but also required for the fulfillment of human character. When politics is so conceived, a reaction against conventional politics understandably follows.

There are, of course, other familiar grounds for the dismissal or suspicion of “electoral politics.” People who either challenge or reject the validity of contemporary American democracy find it infuriating to hear that the regularity, frequency, and integrity of American elections are the proof and essence of the nation’s democratic character. Even more familiar are arguments that American elections and campaigns are fraudulent anyway, that the parties offer no real choices, and that, in any case, the results of elections have little or no effect on public policy, because the elected officials do not really set the policy. Such views have been staples of radical discourse for a long time.

But there is another, more subtle and, in the long run, possibly more significant reserve toward “electoral politics” from many of the younger Berkeley radicals. It is usually expressed in that austere, stiff-necked, and almost complacent fashion that can so infuriate older political activists. It goes something like this: Electoral politics are intrinsically corrupting. In electoral politics, initial movement objectives inexorably change into the goal of victory for the candidates. The goal of victory for the candidates, in turn, demands compromise, jettisoning of principle.

The candidates, in their turn, become “stars” and in so doing are themselves corrupted by vanity and ambition. They begin to serve themselves rather than the movement. They cultivate the arts of winning approval, change their dress, their language, their personal style. Beyond that, if these efforts succeed and candidates win office, the movement feels committed to them, obliged to support them in their legislative maneuverings. In such circumstances, what becomes of the movement?

To veterans of political campaigns much of this may seem foolish, but it suggests a mood which is pervasive among young radicals in Berkeley. I talked to dozens of them, many of whom had given up virtually all other activity to work through the winter for the Community Control amendment and for the Coalition candidates and platform. All of them expressed some variant of this view.

That the mood I’ve described threatens any sustained coalition of students, intellectuals, blacks, chicanos, workers, and old people should be obvious. The contradictions of interest among them had distinct echoes in the Berkeley campaign. People do not like to talk about it but the questions get asked. Did Dellums mute his support for community control of police because he sensed that it was unpopular with the black community? Did the two black Coalition candidates, D’Army Bailey and Ira Simmons, go all out for the amendment or did they concentrate on getting themselves elected?

It is only a step from such questions to the more insistent and important one. What, for white student radicals, is the price of coalition with the blacks? Does one reassert the primacy of interests over principle? Does one give up the cultural elements of the revolution in deference to the blacks’ demand for a system within which they can rise, to their plain need for representation, for influence over policy right now? Such questions can be stifled for a time, but they will not go away for they are inherent in the radicals’ fear of electoral politics.

The purpose of the April Coalition was primarily to enter electoral politics, to win control over the Berkeley city government. Its original organizers and workers came out of past campaigns but mainly from the Dellums campaign of 1970. In some ways it was a residual inheritor of the “radicalization” of many Berkeley people after the battle of People’s Park. The Coalition was a coming together of virtually the entire Berkeley left: The Berkeley Black Caucus, Ecology Action, The Student April 6th Movement, the initiating Berkeley Coalition, and the New Democratic Coalition were only the principal groups. Only the Trotskyists chose to stay apart. To the veteran Berkeley left, 1971 offered a breathtaking possibility. Four members of the City Council were to be elected and no incumbents, not even the Mayor, would be running. If a slate of four radicals could win all of the Council seats and help to elect a sympathetic Mayor (Widener), they would have a majority of five on a council of nine.

Moreover, if elected, Widener would have to resign his own Council seat to serve as Mayor and the radical majority could then appoint a fifth radical Council member, thus giving them a two-thirds majority. A two-thirds majority would make it possible to fire the city manager, fire the police chief and other department heads, and set in motion the transformation of Berkeley from a professionally administered city to one governed through a more direct political process. The city would have a full-time, paid City Council with control over its own budget and the power to appoint department heads and commissioners responsible to it. From such a position, moreover, it would be possible to decentralize the police and establish citizen grievance procedures independent of the police department and to move on to handing more and more power over planning and decision making to the neighborhoods.

The vision of the older radicals who launched the April Coalition, then, did not quite match the sweeping neighborhood participatory democracy that runs throughout the platform ultimately adopted by the April Coalition, but it is clearly informed by the same spirit. The full platform of the April Coalition was adopted in January after a week of open hearings in which perhaps 900 people participated. It is an amazing document. It embraced as its first objective, of course, passage of the police amendment, which was to be binding on all candidates. It called for a complete “restructuring” of city government along the lines of community participation though with greater emphasis on neighborhood control and on processes of open discussion. It proposed new systems of taxation to get the burden off home owners, substituting taxes on individual incomes over $10,000 and higher levies on business and income property owners.

It proposed dozens of new services for the city to meet, most of them oriented to the needs of the poor, the young, the black, the addicted, the afflicted, and the oppressed. It appealed for liberation of women. It stood up for the gay people. It was in favor of sensuality and organic gardening. It called for more kid power in the schools and for decency and concern for the old. It put down the nuclear family and demanded encouragement for those who want to experiment with other styles of life. It was opposed to the automobile and parking lots and in favor of parks and playgrounds. It favored the pedestrian and the cyclist over the motorist. It bristled with hostility to the cops, the University of California, and all bureaucracies.

It would be easy to mock the platform, for its language though impassioned is not eloquent. At first glance it appears to speak for the cultural revolution first and of political matters only after that. Much of what it demanded would be unconstitutional in California and, in any case, impossible to pay for out of current city revenues. In the end, it offered not very much to the specific interests of the blacks, the working class, or the middle classes. One could say that it was an unrealistic document and in some important ways be right.

But the platform does speak to the issues of power and of community. Almost naïvely it seeks to re-create the democratic polis. Truly, if all of the neighborhood boards, councils, commissions, and committees called for were to spring into life, the citizens would be able to do little else but meet and enact the laws. Upon reading the platform, one is apt to experience a surge of nostalgia for the liberal theory of the private citizen who only occasionally and with reluctance enters the public sphere. On the other hand, one might be reminded of those words put into the mouth of Pericles by Thucydides:

The great impediment to action is, in our opinion, not discussion, but the want of that knowledge which is gained by discussion preparatory to action.

Or, as Rousseau, with the messiness of direct action in mind, put it, ‘Where right and liberty are everything, inconvenience matters little.”

After completing its platform, the April Coalition chose its candidates for the four Council seats: two elegant young lawyers, Simmons and Bailey, from the Black Caucus, Rick Brown from the Student April 6th Movement, and Ilona Hancock from the Berkeley Coalition. With the liberal and conservative opposition divided among twelve other candidates, of whom only one (who was subsequently elected) was able to draw the support of the whole opposition, with 10,000 new registered voters signed up by the Dellums campaign of the fall, with a student and street community mobilized by the police control amendment, and with four articulate and attractive candidates running, the Coalition swept to a remarkable victory. Bailey, Simmons, and Hancock were elected outright, and Brown ran a strong fifth in the field of sixteen. There is some chance that Hancock, Simmons, and Bailey can join with Mayor Widener to force the appointment of Brown to fill Widener’s vacated seat. In that case Berkeley would have a radical majority on its Council.

There will be difficulties, to be sure. The differences in the voting patterns of the white radicals and the blacks are troublesome. It is not at all clear that the students and street people are committed to radical politics rather than to the cultural revolution. There is the continuing suspicion of and coolness toward “electoral politics” on the part of many radicals. Still, an American city is about to undertake an astonishing experiment. It is well begun. Though Berkeley is only one city, who on the left would not want to say, as Hamilton said of the great experiment of 1787-88, “[It] is a prodigy, to the completion of which I look forward with trembling anxiety.”

PREAMBLE TO THE APRIL COALITION PLATFORM

We, the citizens of Berkeley, intend to reassert control over our own lives. We have seen our governments destroy beautiful parks and homes while our people cannot get adequate housing or jobs. We have seen our waters polluted and our fellow citizens choked on smog and tear gas, and beaten in the streets.

And yet, despite our oppression, the people of Berkeley continue to work and love. We continue to build our parks and gardens. In our public schools we continue to work both for racial harmony and self determination; and in our families and our free schools we continue to devise new ways to bring up children and to relate to one another as free human beings. We have struggled to create a new consciousness of our womanhood and manhood.

We try, with our limited means, to overcome the heartlessness of our economic system, by sharing our food and our homes, and by setting up clinics for our sick—all without the help of the established powers.

And in the jaws of a government which cares more for the speculations and profits of the rich than for the health and safety of its people, we have brought forth a new birth of direct community democracy.

Now, through an open process that has confidence in all the people, we come together to draw up our program; to choose the representatives who will help us to implement that program; and to encourage all our fellow citizens to assume the human responsibility and privilege of self-government.

This Issue

June 3, 1971