A white silky beach just south of Madras. Blue sea full of sharks, blue sky full of clouds like egret plumes. Nearby, half in the water, half on the beach, the gray-violet pyramid of a Hindu temple gradually dissolving as the sea with each century rises. In the foreground, the body of a man, headless, armless, with only one leg whose flesh stops at the knee. Below the knee, a bright beautiful white bone around which a rope has been knotted. The angle of the bone indicates that the man’s legs and arms had been tied together behind him. Coolly, I become coroner. Speculate sagely on the length of time the man has been dead. Draw my companions’ attention to the fact that there is not a drop of blood left in the body: at first glance we thought it a scarecrow, a bundle of white and gray rags—then saw real muscles laid bare, ropy integuments, the shin bone, and knew someone had been murdered, thrown into the sea alive. But who? And why? Definitely not Chinese, I decide (not only am I at heart a coroner—redundancy—but I am also a geographer of Strabo’s school).

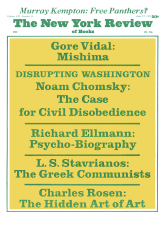

I am interrupted by the arrival of a small Tamil girl resembling the late Fanny Brice. She glares at the corpse. “Not nice, not nice at all!” She shakes her head disapprovingly, hopes we won’t get a wrong impression of India. As we do our best to reassure her, we are joined by a friend with a newspaper: Yukio Mishima has committed seppuku (the proper word for harakiri) in the office of Japan’s commanding general; his head was then hacked from his body by an aide…. We read the bloody details with wonder. Such is the power of writing (to those addicted to reading) that the actual corpse at our feet became less real than the vivid idea of the bodyless head of Mishima, a man my exact contemporary whose career in so many ways resembled my own, though not to the degree that certain writers of book-chat in the Fifties thought.

Tokyo, Unbeautiful but alive and monstrously, cancerously growing, just as New York City—quite as unbeautiful—is visibly dying, its rot a way of life. That will be Tokyo’s future, too, but for the moment the mood is one of boom. Official and mercantile circles are euphoric. Elsewhere, unease.

I meet with a leader of the Left currently giving aid to those GIs who find immoral their country’s murder of Asiatics. He is not sanguine about Japan. “We don’t know who we are since the war. The break with the old culture has left us adrift. Yet we are still a family.”

The first thing the traveler in Japan notices is that the people resemble each other, with obvious variations, much the way members of a family do, and this sense of a common identity was the source of their power in the past, all children of an emperor who was child of the sun. But the sun no longer rises for Japan—earth turns, in fact—and the head of the family putters about collecting marine specimens while his children are bored with their new prosperity, their ugly cities, their half-Western half-Japanese culture, their small polluted islands.

I ask the usual question: what do the Japanese think of the Americans? The answer is brisk. “Very little. Not like before. I was just reading an old Osaka newspaper. Fifty years ago a girl writes that her life ambition is to meet a Caucasian, an American, and become his mistress. All very respectable. But now there is a certain…disdain for the Americans. Of course Vietnam is part of it.” One is soon made aware in Tokyo of the Japanese contempt not only for the American imperium but for its cultural artifacts. Though not a zealous defender of my country, I find prodding its Tokyo detractors irresistible, at least in literary matters. After all, for some decades now, Japan’s most popular (and deeply admired) writer has been W. Somerset Maugham.

We spoke of Mishima’s death and the possibility of a return to militarism: two things which were regarded as one by the world press. But my informant saw no political motive in Mishima’s death. “It was a personal gesture. A dramatic gesture. The sort of thing he would do. You know he had a private army. Always marching around in uniform. Quite mad. Certainly he had no serious political connections with the right wing.”

Mishima’s suicide had a shattering effect on the entire Japanese family. For one thing, he was a famous writer. This meant he was taken a good deal more seriously by the nation (family) than any American writer is ever taken by those warring ethnic clans whose mutual detestation is the essential fact of the American way of life. Imagine Paul Goodman’s suicide in General Westmoreland’s office as reported by The New York Times on page 22. “Paul Goodman, writer, aged 59, shot himself in General Westmoreland’s office as a protest to American foreign policy. At first, General Westmoreland could not be reached for comment. Later in the day, an aide said that the General, naturally, regretted Mr. Goodman’s action, which was based upon a ‘patent misunderstanding of America’s role in Asia.’ Mr. Goodman was the author of a number of books and articles. One of his books was called Growing Up Absurd. He is survived by….” An indifferent polity.

Advertisement

But Mishima at forty-five was Japan’s apparent master of all letters, superb jack of none. Or in the prose of a Knopf blurb writer,

He began his brilliantly successful career in 1944 by winning a citation from the Emperor as the highest-ranking honor student at graduation from the Peers’ School. In 1947 he was graduated from Tokyo Imperial University School of Jurisprudence. Since his first novel was published, in 1948, he has produced a baker’s dozen of novels, translations of which have by now appeared in fifteen countries; seventy-four short stories; a travel book; and many articles, including two in English (appearing in Life and Holiday).

About ten films were made from his novels. The Sound of Waves (1956) was filmed twice, and one of Ishikawa’s masterpieces, Enjo, was based on The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1959). Also available in English are the novels After the Banquet (1963) and The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea (1965), and Five Modern No Plays (1957).

He has acted the title role in a gangster film, and American television audiences have seen him on “The Twentieth Century” and on Edward R. Murrow’s “Small World.” Despite a relentless work schedule, Mr. Mishima has managed to travel widely in the United States and Europe. His home is in Tokyo, with his wife and two children.

The range, variety, and publicness of the career sound ominously familiar to me. Also each of us might be said by those innocent of literature to have been influenced (as a certain “news” magazine gaily wrote of Mishima) “by Proust and Gide.” The fact that Proust and Gide resembled one another not at all (or either of us) is irrelevant to the “news” magazine’s familiar purpose—the ever popular sexual smear job which has so long made atrocious the American scene.

The American press, by and large, played up two aspects of the suicide: Mishima’s homosexuality and his last confused harangue to the troops, demanding a return to militarism and ancient virtue. The Japanese reaction was more knowledgeable and various than the American. It was also occasionally dotty. Professor Yozo Horigome of Tokyo University found “a striking resemblance” between Mishima’s suicide and the death of Thomas à Beckett, as reported by T.S. Eliot! Apparently the good professor had been working up some notes on Eliot and so absorbed was he in his task that any self-willed death smacked of high jinks at Canterbury Cathedral. Taruho Inagaki thought that by extraverting his narcissism Mishima could not continue as writer or man. Inagaki also observed, somewhat mysteriously, that since Mishima lacked “nostalgia,” his later work tended to be artificial and unsatisfactory.

Professor Taku Yamada of Kanazawa University compared Mishima’s suicide to that of an early nineteenth-century rebel against the Shogunate—a virtuous youth who had been influenced (like Mishima) by the fifteenth-century Chinese scholar Wang Yang-ming who believed that “to know and to act are one and the same.” The Japanese, the professor noted, in adapting this philosophy to their own needs, simplified it into a sort of death cult with the caveat “one is not afraid of the death of body, but fears the death of mind.” Yamada seems to me to be closest to the mark, if one is to regard as a last will and testament Mishima’s curious apologia Sun and Steel, published a few months before his death.

The opening sentences set the tone:

Of late, I have come to sense within myself an accumulation of all kinds of things that cannot find adequate expression via an objective artistic form such as the novel. A lyric poet of twenty might manage it, but I am twenty no longer.

Right off, the obsession with age. In an odd way, writers often predict their own futures. I doubt if Mishima was entirely conscious when he wrote Forbidden Colors at the age of twenty-five that he was drawing a possible portrait of himself at sixty-five: the famous, arid man of letters Shunsuké (his first collected edition was published at forty-five) “who hated the naked truth. He held firmly to the belief that any part of one’s talent…which revealed itself spontaneously was a fraud.” The old writer amuses himself during his last days by deliberately corrupting a beautiful youth (unhappily, the aesthetic influence of Dorian Gray is stronger here than that of Les Liaisons Dangereuses) whose initials are—such is the division even at twenty-five in Yukio Mishima—Y.M. The author is both beautiful blank youth and ancient seducer of mind. At the end the youth is left in limbo, heir to Shunsuké who, discreetly, gratefully, kills himself having used Y.M. to cause considerable mischief to others.

Advertisement

Mishima’s novels are pervaded with death. In an early work, Thirst for Love (1950), a young widow reflects that “it was an occult thing, that sacrificial death she dreamed of, a suicide proffered not so much in mourning for her husband’s death as in envy of that death.” Later, in Forbidden Colors, “Suicide, whether a lofty thing or lowly, is rather a suicide of thought itself; in general, a suicide in which the subject does not think too much does not exist.” Not the most elegant of sentences. The translator A.H. Marks usually writes plain American English with only an occasional “trains shrilling” or women “feeling nauseous.” Yet from Mr. Marks’s prose it is hard to determine whether or not Mishima’s writing possesses much distinction in the original. I found Donald Keene’s rendering of the dialogue of Mishima’s No plays unusually eloquent and precise, the work of a different writer, one would say, or is it (heart sinking) simply the distinguished prose of a different translator who has got closer to the original? Unable to read Japanese, I shall never know. Luckily, United Statesmen have no great interest in language, preferring to wrestle with Moral Problems, and so one may entirely ignore the quality of the line (which is all that a writer has of his own) in order to deal with his Ideas which are of course the property of all, and the least interesting thing about him.

Mishima refers to Sun and Steel as “confidential criticism.” He tells us how he began his life as one besotted with words. And although he does not say so directly, one senses from his career (fame at nineteen, a facility for every kind of writing) that things were perhaps too easy for him. It must have seemed to him (and to his surprisingly unbitter contemporaries) that there was nothing he could not do in the novel, the essay, the drama. Yet only in his reworking of the No plays does he appear to transcend competence and make (to a foreign eye) literature. One gets the impression that he was the sort of writer who is reluctant to take the next hard step after the first bravura mastery of a form. But then he was, he tells us, aware from the beginning of “two contradictory tendencies within myself. One was the determination to press ahead loyally with the corrosive function of words, to make that my life’s work. The other was the desire to encounter reality in some field where words should play no part.”

This is the romantic’s traditional and peculiar agony. There is no internal evidence that Mishima read D.H. Lawrence (his rather insistent cultural references consist of hymns in the Winckelmann manner to Greek statuary and the dropping of names like Pater, Beardsley, Poe, Baudelaire, de Sade), but one recognizes a similar tension in Mishima’s work. The fascination with the bodies of others (in Mishima’s case the young male with a “head like a young bull,” “rows of flashing teeth”—sometimes it seems that his ideal is equipped with more than the regulation set of choppers—“wearing sneakers”), and the vain hope of somehow losing oneself in another’s identity, fusing two bodies into something new and strange. But though homosexual encounters are in themselves quite as exciting as heterosexual encounters (more so, claim the great pederasts whose testimony echoes down the ages), it is not easy to build a universal philosophy on a kind of coupling that involves no procreative mystery—only momentary delight involving, if one is so minded, the enactment of ritual, the imposition of fantasy, the deliberate act of imagination without which there is no such thing as love or its philosophy romanticism.

To judge from Mishima’s writing, his love ritual was a complex one, and at the core of his madness. He quickly tired of that promiscuity which is so much easier for the homosexualist than for the heterosexualist. More to the point, Mishima could not trick himself into thinking, as Lawrence could, that a total surrender to the dark phallic god was a man’s highest goal. Mishima was too materialistic, too flesh-conscious for that. As for his own life, he married, had two children. But apparently sought pleasure elsewhere. A passage from one of the novels sounds as if taken from life. Mishima describes the bedding of a new husband and wife.

Yuichi’s first night had been a model of the effort of desire, an ingenious impersonation that deceived an unexperienced buyer…. On the second night the successful impersonation became a faithful impersonation of an impersonation…. In the dark room the two of them slowly became four people. The intercourse of the real Yuichi with the boy he had made Yasuko into, and the intercourse of the makeshift Yuichi—imagining he could love a woman—with the real Yasuko had to go forward simultaneously.

One looks forward to the widow Mishima’s memoirs.

In Sun and Steel Mishima describes the flowering of his own narcissism (a noun always used in a pejorative sense by the physically ill-favored) and his gradual realization that flesh is all. What is the “steel” of the title? Nothing more portentous than weight-lifting, though he euphemizes splendidly in the French manner. Working on pecs and lats, Mishima found peace and a new sense of identity. “If the body could achieve perfect, non-individual harmony, then it would be possible to shut individuality up forever in close confinement.” It is easy to make fun of Mishima, particularly when his threnody to steel begins to sound like a brochure for Vic Tanney, but there is no doubt that in an age where there is little use for the male body’s thick musculature, the deliberate development of that body is as good a pastime as any, certainly quite as legitimate a religion as Lawrence’s blood consciousness, so much admired in certain literary quarters.

To Mishima the body is what one is; and a weak sagging body cannot help but contain a spirit to match. In moments of clarity (if not charity) Mishima is less stern with the soft majority, knows better. Nevertheless, “bulging muscles, a taut stomach and a tough skin, I reasoned, would correspond respectively to an intrepid fighting spirit….”

Why did he want this warrior spirit? Why did he form a private army of dedicated ephebi? He is candid.

Specifically, I cherished a romantic impulse toward death, yet at the same time I required a strictly classical body as its vehicle; a peculiar sense of destiny made me believe that the reason why my romantic impulse toward death remained unfulfilled in reality was the immensely simple fact that I lacked the necessary physical qualifications.

There it is. For ten years he developed his body in order to kill it ritually in the most public way possible.

This is grandstanding of a sort far beyond the capacity of our local product. Telling Bobby Kennedy to go fuck himself at the White House is trivial indeed when compared to the high drama of cutting oneself open with a dagger and then submitting to decapitation before the army’s chief of staff.

It should be noted, however, that Japanese classicists were appalled. “So vulgar,” one of them told me, wincing at the memory. “Seppuku must be performed according to a precise and elegant ritual, in private, not [a shudder] in a general’s office with a dozen witnesses. But then Mishima was entirely Westernized.” I think this is true. Certainly Mishima seldom makes any reference to Japanese literature in his work. He is devoted to French nineteenth-century writing, with preference for the second-rate—Huysmans rather than Flaubert. In fact, his literary taste is profoundly corny, but then what one culture chooses to select from another is always a mysterious business. Gide once spoke to me with admiration of James M. Cain, adding, quite gratuitously, that he could not understand why anyone admired E.M. Forster.

Mishima dreamed of a revival of the Heian ideal: that extraordinary culture which insisted that physical strength and aesthetic sense ought to be united in the same man. Certainly Mishima had come to believe that the beauty of the sword was:

…in its allying death not with pessimism and impotence but with abounding energy, the flower of physical perfection and the will to fight. Nothing could be farther removed from the principle of literature. In literature, death is held in check yet at the same time used as a driving force; strength is devoted to the construction of empty fictions; life is held in reserve, blended to just the right degree with death, treated with preservatives, and lavished on the production of works of art that possess a weird eternal life. Action—one might say—perishes with the blossom. Literature is an imperishable flower. And an imperishable flower, of course, is an artificial flower. Thus to combine action and art is to combine the flower that wilts and the flower that lasts forever….

It is often wise (or perhaps compassionate is the better word) to allow an artist if not the last the crucial say on what he meant to make of himself and his life. Yet between what Mishima thought he was doing and what he did there is still confusion. When I arrived in Japan journalists kept asking me what I thought of his death. At first I thought they were simply being polite. I was vague, said I could not begin to understand an affair which seemed to me so entirely Japanese. I spoke solemnly of different cultures, different traditions. Told them that in the West we kill ourselves when we can’t go on the way we would like to: a casual matter, really—there is no seppuku for us, only the shotgun or the bottle. But now that I have read Sun and Steel and a dozen of Mishima’s early works, some for the first time, I see that what he did was entirely idiosyncratic, more Western in its romanticism than Japanese, which explains why his countrymen were genuinely eager to know what a Western literary man thought. Here then, belatedly, the coroner’s report on the headless body in the general’s office.

Forty-five is a poignant time for the male, particularly for one who has been acutely conscious of his own body as well as those of others. Worshipping the flesh’s health and beauty (American psychiatrists are particularly offended by this kind of obsession) is as valid an aesthetic—even a religion—as any other, though more tragic than most, for in the normal course half a life must be lived within the ruin of what one most esteemed. For Mishima the future of that body he had worked so hard to make worthy of a classic death (or life) was somber. Not all the sun and steel can save the aging athlete.

Yet Mishima wanted a life of the flesh, of action, divorced from words. Some interpreted this to mean that he dreamed of becoming a sort of warlord, restoring to Japan its ancient military virtues. But I think Mishima was after something much simpler: the exhaustion of the flesh in physical exercise, in bouts of love, in such adventures as becoming a private soldier for a few weeks in his middle age or breaking the sound barrier in a military jet.

Certainly he did not have a political mind. He was a Romantic Artist in a very fin de siècle French way. But instead of deranging the senses through drugs, Mishima tried to lose his conscious mind (his art) through the use and worship of his own flesh and that of others. Finally, rather than face the slow bitter dissolution of the incarnate self, he chose to die. He could not settle for the common fate, could not echo the healthy dryness of the tenth-century poet (in the Kokinshu) who wrote: “If only when one heard / that old age was coming / one could bolt the door / and refuse to meet him!.” The Romantic showman chose to die as he had lived, in a blaze of publicity.

Now for some moralizing in the American manner. Mishima’s death is explicable. Certainly he has prepared us, and himself, for it. In a most dramatic way the perishable flower is self-plucked. And there are no political overtones. But what of the artificial flowers he left behind? Mishima was a writer who mastered every literary form, up to a point. Reading one of his early novels, I was disturbed by an influence I recognized but could not place right off. The book was brief, precise, somewhat reliant on coups de théâtre, rather too easy in what it attempted but elegant and satisfying in a conventional way like…like Anatole France whom I had not read since adolescence. Le Lys rouge, I wrote in the margin. No sooner had I made this note than there appeared in the text the name Anatole France. I think this is the giveaway. Mishima was fatally drawn to what is easy in art.

Technically, Mishima’s novels are unadventurous. This is by no means a fault. But it is a commentary on his art that he never made anything entirely his own. He was too quickly satisfied with familiar patterns and by no means the best. Only in his reworking of the No plays does Mishima, paradoxically, seem “original,” glittering and swift in his effects, like Ibsen at the highest. What one recalls from the novels are his fleshly obsessions and sadistic reveries: invariably the beloved youth is made to bleed while that sailor who fell from grace with the sea (the nature of this grace is never entirely plain) gets cut to pieces by a group of adolescent males. The conversations about art are sometimes interesting but seldom brilliant (in the American novel there are no conversations about art, a negative virtue but still a virtue).

There is in Mishima’s work, as filtered through his translators, no humor, little wit; there is irony but of the W. Somerset Maugham variety…things are not what they seem, the respectable are secretly vicious. Incidentally, for those who think that Japanese culture is heavy, portentous, bloody, and ritual-minded (in other words, like Japanese samurai films), one should point out that neither of the founders of Japanese prose literature (the Lady Muraski and Sei-Shonagon) was too profound for wit. In Sei-Shonagon’s case quite the contrary.

As Japan’s most famous and busy writer, Mishima left not a garden but an entire landscape full of artificial flowers. But, Mishima notwithstanding, the artificial flower is quite as perishable as the real. It just makes a bigger mess when you try to recycle it. I suspect that much of his boredom with words had to do with a temperamental lack of interest in them. The novels show no particular development over the years and little variety. In the later books, the obsessions tend to take over, which is never enough (if it were, the Marquis de Sade would be as great a writer as the enemies of art claim).

Mishima was a minor artist in the sense that, as Auden tells us, once the minor artist “has reached maturity and found himself he ceases to have a history. The major artist, on the other hand, is always re-finding himself, so that the history of his works recapitulates or mirrors the history of art.” Unable or unwilling to change his art, Mishima changed his life through sun, steel, death, and so became a major art-figure in the only way—I fear—our contemporaries are apt to understand: not through the work, but through the life. Mishima can now be ranked with such “great” American novelists as Hemingway (who never wrote a good novel) and Fitzgerald (who wrote only one). So maybe their books weren’t so good, but they sure had interesting lives, and desperate last days. Academics will enjoy writing about Mishima for a generation or two. And one looks forward to their speculations as to what he might have written had he lived. Another A la recherche du temps perdu? or Les caves du Vatican? Neither, I fear. My Ouija board has already spelled out what was next on the drawing board: “Of Human Bondage.”

Does any of this matter? I suspect not. After all, literature is no longer of very great interest even to the makers. It may well be that that current phenomenon, the writer who makes his life his art, is the most useful of all. If so, then perhaps Mishima’s artificial flowers were never intended to survive the glare of sun and steel or compete with his own fleshly fact, made bloody with an ax. What, after all, has a mask to confess except that it covers a skull? All honor then to a man who lived and died the way he wanted to. I only regret we never met, for friends found him a good companion, a fine drinking partner, and fun to cruise with.

This Issue

June 17, 1971