In response to:

Criminal Behavior from the June 3, 1971 issue

To the Editors:

Like many others I tend to confuse what a reviewer says with the book itself. It’s so much easier. “Well, I haven’t read the book, but the review says….”

After reading Richard Wasserstrom’s review of Telford Taylor’s Nuremberg and Vietnam [NYR, June 3], I was, therefore, inclined to believe that Mr. Taylor had missed the main issues, that his book is, indeed, “dangerous,” “inadequate,” and “defective.” Then I read the book.

Mr. Wasserstrom’s review is inadequate and defective. I offer some examples.

- Mr. Wasserstrom accuses Mr. Taylor of rejecting American war guilt for bombing Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. He claims Mr. Taylor writes as if “there is nothing wrong with bombing population centers…. They [the bombings] certainly do end up killing lots of civilians…. But that just cannot be helped because a bomb…cannot discriminate between combatants and non-combatants. What is more, bombing is an inherently inaccurate undertaking….”

Actually, Mr. Taylor is talking about the Second World War in the passage his reviewer paraphrases, and even there Mr. Taylor suggests that Nagasaki and Dresden probably constituted war crimes. As for Vietnam, not only does Mr. Taylor explicitly condemn the attacking of villages and hamlets in the South (as Mr. Wasserstrom concedes) but also airstrikes against “free strike zones” in which individuals may come under fire as described by Jonathan Schell and others. These latter, Mr. Taylor contends, are “unlawful for the same reasons that the Son My killings were unlawful.”

- Mr. Wasserstrom charges Mr. Taylor with deflecting “our attention from those who are most responsible for our presence there [Vietnam].” What, then, does he make of Mr. Taylor’s final judgment (p. 205): “The war, in the massive, lethal dimensions it acquired after 1964, was the work of highly educated academics and administrators, most of whom would fit rather easily the present Vice-President’s notion of an ‘effete snob.’ It was not President Kennedy himself, but the men he brought to Washington as advisers and who stayed on with President Johnson—the Rusks, McNamaras, Bundys, and Rostows—who must bear major responsibility for the war and the course it took.”

- Far from avoiding “what we are doing to the civilian populations of Southeast Asia,” Mr. Taylor quotes copiously from the Kennedy Committee on Refugees, Richard Hammer, Jonathan Schell, Colonels William Corson and James Donovan, Robert Lifton, Gabriel Kolko—and attacks Town-send Hoopes.

Mr. Wasserstrom may feel that Mr. Taylor’s analysis is not damning enough. I agree. John Kennedy does share a major responsibility for the Vietnamese war, as do others before him. But to dismiss Telford Taylor’s book as “dangerous” is to distort and diminish an important contribution to consciousness-raising.

Jonathan Mirsky

Co-Director

East Asia Language & Area Studies Center

Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H.

Richard Wasserstrom replies:

I do not think that I misunderstood Telford Taylor’s book, nor do I think I misrepresented it. I was concerned in my review to delineate that conception of war and the laws of war that dominates the book, and to indicate the respects in which Taylor’s concentration upon these issues seems to me to be open to serious criticism. Mr. Mirsky’s examples appear to me to advance, rather than to detract from, my argument. The first two are the more important ones, so I will comment only on them.

- Bombing—I think that one of the most fundamental distinctions that ought to be made, even in war, is the distinction between those who are combatants and those who clearly are not (the easiest case being, perhaps, small children). I think it appropriate to criticize the conception of the laws of war described by Taylor on the ground that, in respect to bombing, it captures this distinction hardly at all! I think it appropriate to criticize Taylor, therefore, for taking as the absolutely central question that of whether the laws of war were violated. To be sure, he does condemn the bombing of villages and hamlets in the South, but only if they are bombed in reprisal for having harbored Viet Cong, and not if they are bombed because Viet Cong may be in the village (p. 145). I do not think that this is the heart of the matter, because I do not understand why it is not also wrong to bomb villages in which women and children are trying to live, even if Viet Cong may be there too.

-

Who is most responsible? The passage on p. 205 that Mr. Mirsky quotes follows immediately upon a discussion of approximately twenty pages in which Taylor presents a variety of arguments to show that we used the wrong military tactics in Vietnam and had the wrong objectives. What is crucial, though, is that “wrong” in this context clearly means inappropriate, unproductive, misguided, etc., and not immoral or criminal. The responsibility that he would have the named individuals bear is the responsibility for having led the United States on an adventure that was destined to fail. The point of my criticism was and is that the evil of our involvement in Vietnam is substantially unaffected by the fact that the “realists” in Washington failed to achieve their objective.

In the final paragraph of the book Taylor says: “One may well echo the acrid French epigram and say that all this ‘is worse than a crime, it is a blunder’—the most costly and tragic national blunder in American history” (p. 207). I do think Taylor’s point of view is defective, inadequate, and dangerous because unlike him (and the French, apparently) I happen to believe that crimes are much worse than blunders.

This Issue

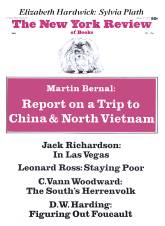

August 12, 1971