To the Editors:

Presidential press secretary Herbert G. Klein reported (The New York Times, December 1, 1971) to President Nixon his “feeling” that the socialist government of President Salvador Allende in Chile “won’t last long.” Klein may know what we suspect—that tensions in Chile reflect the work of powers far greater than the 5,000 women who recently marched to protest a food shortage.

In fact, Chile’s food shortages and economic difficulties have been exploited by President Allende’s opposition and misunderstood by the US press. In its first year of power, the Allende government has stimulated economic growth and begun to redistribute income through higher wages for workers, which in turn created a significant rise in the demand for consumer goods (including food) and services.

Moreover, Allende inherited Chile’s food shortages, caused by an inefficient and unequitable agricultural system. Shortages of such items as meat, milk, and coffee became marked during the Christian Democratic Administration of Eduardo Frei (1964-70). By early 1970, months before Allende’s victory, Chilean markets sold meat only a few days of each month, and the milk supply was sporadic. After Allende’s inauguration (November, 1970), new obstacles were thrown in the way of food production: 1) indiscriminate slaughtering of herds and refusal to plant by landowners whose properties faced expropriation; 2) the earthquake and resulting dam age in July, 1971; and 3) the heavy snows, which killed crops and poultry.

The upper class (which these 5,000 women represented) never experienced hunger pangs, as Chile’s poor have for decades. Only when meat became difficult to obtain under Allende did these privileged women march in the streets with empty pots which had previously been used only by their servants.

More than a year ago, shortly after Allende’s election, the Chilean press reported that upper-class rightist women rallied to urge the military to intervene to block Allende’s election and ignore Chile’s constitution. Later rightists assassinated Army Chief of Staff General Schneider, hoping to provoke a coup by attributing the murder to left-wing militants. But when the rightists were apprehended and the plot exposed, the military’s commitment to constitutional procedure was actually strengthened.

The recent disruptions demonstrate the right’s determination to overthrow Allende’s government and stop programs designed for the welfare of the Chilean poor. Herbert Klein’s statement may express US policy rather than his “feeling.” As individuals who believe the US government should keep its hands off Chile’s internal political affairs, we are alarmed and angered by Klein’s statement, and we reaffirm our support for the Popular Unity government as it struggles to meet the needs of the Chilean people.

Elizabeth Farnsworth, Saul Landau, Paul Jacobs, Haskell Wexler, Nina Serrano

San Francisco, California

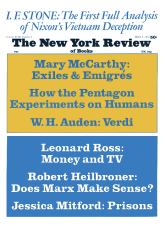

This Issue

March 9, 1972