Struggle for Justice, a report by a Working Party of the American Friends Service Committee, forgoes the well-worn theme of what’s wrong with prisons; instead it dissects the theory and practice of prison reform to show why most of the panaceas now being discussed would only make things worse. Maximum Security is a collection of letters from inmates undergoing the ultimate “correction” in the Adjustment Centers of the California prison system.

“After more than a century of persistent failure,” say the authors of Struggle for Justice, “the reformist prescription is bankrupt.” They summarize this prescription as follows:

More judges and more “experts” for the courts, improved educational and therapeutic programs in penal institutions, more and better trained personnel at higher salaries, preventive surveillance of predelinquent children, greater use of probation, careful classification of inmates, preventive detention through indeterminate sentences, small “cottage” institutions, halfway houses, removal of broad classes of criminals (such as juveniles) from criminal to “nonpunitive” processes, the use of lay personnel in treatment—all this paraphernalia of the “new” criminology appears over and over in nineteenth-century reformist literature.

Anyone with the fortitude to read that forbidding literature will immediately recognize the formula. For example, the Declaration of Principles adopted by the first congress of the American Prison Association in 1870: “Since treatment is directed to the criminal rather than to the crime, its great object should be his moral regeneration…not the infliction of vindictive suffering.” The congress called for classification of criminals “based on character”; the indeterminate sentence under which the offender would be released as soon as the “moral cure” had been effected and “satisfactory proof of reformation” obtained; “preventive institutions for the reception and treatment of children not yet criminal but in danger of becoming so”; education as a “vital force in the reformation of fallen men and women”; and prisons of “a moderate size,” preferably designed to house no more than 300 inmates.

Or the report of the Wickersham Commission, appointed by President Hoover in 1931:

We conclude that the present prison system is antiquated and inefficient. It does not reform the criminal. It fails to protect society. There is reason to believe that it contributes to the increase of crime by hardening the prisoner. We are convinced that a new type of penal institution must be developed, one that is new in spirit, in method, and in objective.

The commission recommends: individual treatment…indeterminate sentence…education in the broadest sense…skillful and sympathetic supervision of the prisoner on parole…etc.

Skip now to The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society, the 1967 report of the President’s Crime Commission, which calls for more intensive parole supervision, establishment of “model, small-unit correctional institutions,” the strengthening of screening and diagnostic resources “at every point of significant decision,” the upgrading of educational and vocational training programs.

These calls for reform invariably follow in the wake of riots and strikes by prisoners protesting intolerable conditions. Thus the pattern over the past century tends to be circular: an outbreak of prison disturbances—followed by newspaper clamor for investigation—followed by broad agreement that prisons are horrible, destructive places fulfilling none of their supposed objectives—followed by a restatement of the penological nostrums of preceding decades.

Struggle for Justice is a powerful reply to the stale reformist prescription. In this short book the authors (of whom several are convicts) have cut through all the benevolent-sounding verbiage to show that the “individualized treatment model” was initially, is now, and ever shall be primarily a means of maintaining maximum control over the convict population while assuaging the public conscience with the promise of “imprisonment-for-rehabilitation” as opposed to “imprisonment-for-punishment.” This, they say, accounts for its enthusiastic acceptance by a most unlikely collection of bedfellows: liberal reformers, prison administrators, judges, prosecutors, law enforcement officers.

The notion that most lawbreakers are suffering from mental illness—else why should they transgress?—took hold among prison people at a surprisingly early date, long before psychiatric explanations for all manner of human behavior became fashionable. Thus a speaker at the 1874 congress of the American Prison Association: “Abolish all time sentences. Treat the criminal as a patient, and the crime as a disease.”*

The authors of Struggle for Justice dispute this contention as unproved and suggest that the persistent branding of lawbreakers as sick or abnormal may be a mask to hide “the mixture of hatred, fear, and revulsion that white, middle-class, Protestant reformers” feel toward lower-class persons who do not share their Christian middle-class ethic; these difficult, contradictory feelings are “disguised as humanitarian concern for the ‘health’ of threatening subculture members.”

The purpose of “treatment”—in prison parlance, an umbrella term meaning diagnosis, classification, prediction of future behavior—is to force conformity to this ethic. The cure is deemed effective to the degree that the lower-class deviant appears to have adopted the virtues of industry, cleanliness, docility, subservience to authority.

Advertisement

From the convict’s point of view treatment is a humiliating game the rules of which he must learn in order to placate his keepers and manipulate the parole board at his annual hearing: “I have gained much insight into my problems during the past year.” Anyone who refuses to submit to treatment will find himself “diagnosed” as a troublemaker, and his custody classification (maximum, medium, or minimum security) will be accordingly maximum. Furthermore if he declines to play the “treatment” game he may serve months or years more than is normal for his offense. A former convict told me about an Indian prisoner in San Quentin serving an indeterminate sentence of one to fifteen years for burglary; as a first offender, he would ordinarily have been paroled after a year or so. For eight consecutive years the parole board refused to set a release date because he would not go to group therapy. In the ninth year, he escaped.

For the prison administrator the treatment philosophy provides a convenient justification for secret procedures, unreviewable decisions, and unquestioned discretionary power over those in his custody. By relying on the indeterminate sentences given prisoners he can hold almost indefinitely in what amounts to preventive detention those he considers unfit for release. The fact that there is no known way of predicting human behavior does not deter him from slapping the “potentially violent” label on any prisoner who seems to threaten the stability of the institution, the persistent jail house lawyer or the leader of an ethnic group or the political dissident.

The fate of a man so labeled will likely be solitary confinement as well as an additional term of imprisonment. Thus a court found that Martin Sostre, a black militant prisoner in Green Haven, New York, was held in solitary for more than a year—and deprived of 124 days accumulated “good time”—for helping another inmate prepare legal papers and for having “inflammatory” literature in his cell. Lawyers involved in prison litigation say that the treatment accorded Sostre, far from being exceptional, is standard procedure in prisons throughout the country for dealing with inmates who assert their constitutional rights or who challenge institutional policy.

While the “Corrections” crowd everywhere talks a good line of “treatment”—and phrases like “inadequate personality,” “borderline sociopath” come trippingly off the tongue of the latter day “modern” prison administrator who no longer has to cope with the sin-stained souls and fallen men or women in the care of his predecessor—very few prison systems have done much about treatment in practice. Throughout the country, only 5 percent of the Correctional budget goes for services labeled “rehabilitation” and in many prison systems there is in fact no therapy at all available to the adult offender.

To the chronic plaint of the would-be rehabilitator—if the treatment programs have not worked, the reason must be that, owing to public apathy and legislative stinginess, they have never been given a fair chance—the authors of Struggle for Justice reply that “there is compelling evidence that the individualized treatment model, the ideal to which reformers have been urging us for at least a century, is theoretically faulty, systematically discriminatory in administration, and inconsistent with some of our most basic concepts of justice.”

In support of this assertion they point to the California prison system, which is widely accepted as a model for the rest of the country for its espousal of the treatment philosophy and its concomitant, the indeterminate sentence. They cite the work of Norman S. Hayner, a sociologist who compared correctional systems in several countries and concluded that California “easily ranks at the top from the standpoint of emphasis on treatment with a score of 122 points out of a possible 140.”

The effect of this benign emphasis is that the plight of the California convict has steadily worsened. With the introduction in the early Fifties of group therapy, milieu therapy, and other rehabilitative experiments, the median term served by California’s “felony first releases” rose, over two decades, from twenty to thirty-six months, twice the national average. As the 1871 Declaration of Principles put it: “The prisoner must remain [in custody] long enough for virtue to become a habit.”

Nor has the treatment era produced the desired habits of virtue: statistics show that persons who are forced to jump through the hoops of treatment do just about the same as those who receive no treatment at all. In California the rate of recidivism has remained constant over the years, with approximately 40 percent of those released on parole eventually returned to prison.

As the prison crisis deepens the demand to abolish prisons altogether has grown in many quarters, liberal as well as radical. The authors of Struggle for Justice say if there were a choice between prisons as they are now and no prisons at all, they would choose the latter, but they do not believe this is a realistic option in the US. They note “the impossibility of achieving more than a superficial reformation of our criminal justice system without a radical change in our values and a drastic restructuring of our social and economic institutions,” but they believe they must work to change the prison system.

Advertisement

They caution against proposals for prison abolition that are really exercises in label switching: “Call them ‘community treatment centers’ or what you will, if human beings are involuntarily confined in them they are prisons.” They suggest an easy way to test the real intent of the proponents of abolition: Is the proposed alternative program voluntary? Can a person enter at will and leave at will? If the answer is no, “then the wolf is still under the sheepskin.”

In the wake of Attica many scandalized liberals joined with the radicals in embracing the slogan of “Tear Down the Walls.” The test proposed in Struggle for Justice may usefully be applied to this rhetoric. A case in point is a recent headline in the San Francisco Chronicle (November 22, 1971): “Ramsey Clark’s Solution: Abandon Prisons Entirely.” Yet a closer examination of his position as set forth in Crime in America reveals that he is in reality advocating larger doses of the same old reformist prescription. He asserts that “corrections is by far the best chance we have to significantly and permanently reduce crime in America,” and he bestows his unqualified blessing on the indeterminate sentence which, he says, “gives the best of both worlds—long protection for the public yet a fully flexible opportunity for the convict’s rehabilitation…the prisoner would have the chance, however remote, of release at any time. The correctional system would have its opportunity to rehabilitate.” Mr. Clark’s brand of “abolition” adds up to more money for “corrections,” more supervision of the offender at every stage of his progression through the criminal justice system from probation to parole, a vast extension of discretionary power of captor over capitve.

Well aware of the demonstrated capacity of the criminal justice system to absorb well-intentioned reforms and adapt them to essentially punitive purposes, the authors of Struggle for Justice approach their suggestions for change in somewhat gingerly fashion. They offer them not as a blueprint but as “crudely spelled out principles…ways of reducing somewhat the impact of prejudice and discrimination,” for “the construction of a just system of criminal justice in an unjust society is a contradiction in terms.” Some of their proposals have been explored in The New York Review and elsewhere by legal scholars: they would make a broad range of offenses, including prostitution, vagrancy, and drug addiction, non-criminal; they would eliminate the bargaining by which lower prison sentences are obtained by agreements to plead guilty; they would abolish cash bail.

The truly fresh section of Struggle for Justice—and the one that will be considered shocking by both prison administrations and reformers—proposes an alternative to the “individualized treatment model.” Not only has “treatment” failed miserably after decades of experiment, the authors say, but even if it were scientifically feasible its methods and objectives—manipulative routines for the purpose of remolding the young/poor/black/brown “deviants” who fill the prisons to the satisfaction of their white/middle-class/middle-aged captors—are offensive and immoral.

Since society insists on punishment, they advocate the reverse of the “individualized treatment model” and a return to an earlier concept: Let the punishment fit the crime. The law through its representatives in the courts and prisons, they argue, has no business concerning itself with “the whole person,” only with that person’s unlawful acts. Therefore sentences should have a definite duration, they should be uniformly applied, and, to strip away society’s comfortable delusions about the purpose of imprisonment, they should be labeled “punishment” not “rehabilitation.” The authors might also demand the outlawing of some cherished euphemisms of the prison business—for Department of Corrections, substitute Department of Punishment.

Sentences (which for most crimes are longer in the US than in any other Western country) should be much shorter. While there should be a great many educational, medical, psychiatric, vocational, and other services available to prisoners, these should be independent of the prison system with no coercion attached; the prisoner should be free to take them or leave them, his decision in no way affecting length of time served. Parole, beloved of reformers as a “helping service” and loathed by convicts as just an extension of prison servitude, should be abolished and replaced by unsupervised release. The intent of these proposals is to drastically curtail the awesome discretionary power invested in the authorities, from the policeman on the beat to the parole board.

In formulating their proposals the authors observe that the impetus for change is coming from the convicts themselves: “We note the courage of prisoners all over the nation who, at great risk to themselves, point to the barbarity of their confinement, demanding that its causes, not merely its present misery, be changed…we stand beside them in their struggle.”

Maximum Security illustrates this barbarity in its most abysmal form: it tells of confinement in California’s prisons-within-prisons, the hidden fortresses of filthy little concrete cells on which the Department of Corrections has conferred the mind-boggling designation, “Adjustment Centers.” Of the 21,000 convict population in California, between 600 and 700 are thus caged. What are they like?

Their keepers would have us believe that they are depraved, hard-core criminals, the sludge at the bottom of the barrel. In a Foreword to Maximum Security Fay Stender, lawyer for many of the writers, describes her first visit to the Adjustment Center in Soledad prison. As she walked down the tier she shook hands with each inmate through the slots in the bars. A shocked Department of Corrections official warned her not to do this: “We’re so afraid they are going to take a razor and cut your hand off.”

We learn from the letters that many have been driven to madness: “Each day a prisoner is tortured psychologically and spiritually until finally he just leaps in one direction or the other. Maybe he will stab someone else for no reason at all; I’ve seen that. Or maybe he will take a razor blade and slice himself up from head to toe; I’ve seen that, too.” Which should come as no surprise to the prison authorities: for 200 years we have known that prolonged solitary confinement can cause insanity. As one writer says, “Strip cells were and are designed with one purpose in mind…purely and simply to break the inmate’s will. To break the inmate’s spirit.”

Yet the voices we hear in these extraordinarily moving letters are those of men who have managed to hang on to their sanity and preserve their humanity in the face of systematic torments that would drive most of us over the brink. Many of the writers are black or Chicano, “state-raised” graduates of juvenile halls and Youth Authority institutions. Few have had jobs or education. Writing from their dungeons—“nothing but cement and filth,” as one describes the Adjustment Center—they vividly support the principal thesis of Struggle for Justice:

Southern prisons with their overt physical brutality are not nearly as insidious as this enlightened mental torture of everything being indeterminate, never ending, subject to whim, caprice, designed to destroy mind and soul, strip integrity, murder a man’s desire to think as an individual….

…don’t tamper with a man’s soul. Don’t whip his mind. Don’t hand him that shit about rehabilitation. You can beat the flesh and it will soon become accustomed to the pain. But the mind is very, very tender. It can stand so much….

Accompanying the “enlightened mental torture” are beatings, killings; “I could hear the unmistakable sound of a club as it thundered on the bare body of the defenseless prisoner…. I heard the prisoner’s first cry of pain, followed by his pleading for the officers to stop their attack as blow after blow was struck….” “I returned here the next day and I could smell death in the air…they told me that Nolen, Edwards and Miller were shot down like ducks in a pond….”

In her Preface, Eve Pell remarks that the writers, in allowing their letters to be published, risk severe reprisals. This point is underscored by one of them: “I wrote this, I will be punished for it. I hate pain, but I would detest myself if I ceased to think or express the truth.” Thus, Maximum Security forces us to confront the question, who is “sick”? These courageous men or the society that condemns them to such barbarities?

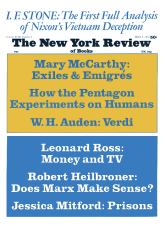

This Issue

March 9, 1972

-

*

The same thought is paraphrased in two recent bestsellers, The Crime of Punishment by Karl Menninger, M.D., and Crime in America by Ramsey Clark. According to Dr. Menninger, unlawful acts are “signals of distress, signals of failure the spasms and struggles and convulsions of a submarginal human being trying to make it in our complex society with inadequate preparation.” Ramsey Clark writes, “Most people who commit serious crimes have mental health problems.” Neither author attempts to document these assertions.

↩