Robert Coles is a child psychiatrist and a man of insight and warm sympathy. These qualifications and ten years of hard and lonely work have enabled him to write a series of books for which the nation will owe him a lasting debt. These books deserve to rank with—and, indeed, transcend—W. A. Cash’s The Mind of the South and James Baird Weaver’s A Call to Action. The two new volumes and their forerunner, A Study of Courage and Fear, are the definitive work on America’s poor and powerless in the twentieth century.

The American democracy—Winston Churchill’s “Great Republic”—is in its very survival a tremendous success story. When one looks back across its history it seems impossible that it could have held together at all in the face of the immense forces that have tended always toward its disintegration. In the beginning it was three and a half million square miles of wilderness—vast and alien and, to Europeans, frightful. It was so immense that as it was divided a single state could be larger than a European empire. Distance between the parts made them foreign to one another, and since strangers are almost inevitably enemies, its regionalism spawned antagonisms and hatreds.

The human materials that built our country in Governor William Bradford’s “hideous wilderness” were, to say the least, unpromising. There were half a million or so red Indians, trusting tribesmen whom white brutality promptly turned into determined and ruthless warriors. There were adventurers in search of gold and land, religious zealots in whom religion often failed to equate with goodness, impoverished younger sons of Old World aristocracies, embittered Scotch-Irish broken by Parliament’s repressive economic policies, Scottish highlanders “cleared” by landlords who wanted to pasture sheep on their fields, multitudes of Germans uprooted by a century-long war, a million terrified Africans herded into the holds of slave ships, Jews fleeing from Russian and Polish pogroms, another million of famine-plagued Irish, penniless peasants from Italy and the Balkans, Chinese coolies hauled in to build railroads, quiet Japanese farmers who heard rumors of the “Golden State”—these and a sprinkling of great scientists and philosophers were among our forebears.

They came in wave after wave for three hundred years, building towns, clearing fields, inventing and applying new tools in response to a gigantic environmental challenge, educating, exploiting one another and the land, greedily piling up private wealth, and always and everywhere squabbling among their own groups and others. The tensions and the misunderstandings erupted in a Civil War that plowed under 650,000 men. They left behind also a legacy of human woe that now appears almost immedicable.

America is a “great” country, as our politicians endlessly remind us. It could have been a much greater and far less troubled country if its people and government had acted with foresight and compassion instead of cruelty or indifference to some of the opportunities afforded by its history.

For example, after Sequoia invented a Cherokee alphabet, that nation and the Creeks and some of their less numerous neighbors turned with alacrity to the white man’s civilization. Old and young alike learned to read and write, achieving a literacy level that has escaped the rest of the nation to this day. They set up courts of law, sent ambassadors to Paris, Madrid, and London, and looked forward to statehood under terms of a treaty signed by George Washington. But during Andrew Jackson’s Presidency their lands were seized, their chattels confiscated, and they were driven across half a continent to the wilds of Oklahoma. There they fell victim to warlike tribes and later to voracious oil tycoons. If cultivated by a wise government they could have led the rest of the native aborigines into self-sufficiency and independence. Instead of another broken treaty, we might have produced land-owning farmers, artisans, artists, judges, physicians, and congressmen. The government chose, instead, to pen them on reservations and the outgrowth has been poverty, helplessness, ignorance, and bitterness.

Then there were the years of reconstruction when a few enlightened congressmen like Thaddeus Stevens sought to save the freedmen. After generations of bondage the nation had a chance to make a new beginning with its blacks. Enlightened self-interest required that the vast estates of Southern rebels be acquired by the government and sold to the blacks on generous terms, that they be schooled and provided with universities, that hospitals be built for their benefit, and that they be guarded and helped until they could shake off their ingrained servility and become free in fact as well as name. The nation chose otherwise and let the rebels keep their land. Federal supports were withdrawn and new generations of white masters kept the blacks in a very real and terrifying bondage.

And, of course, there were the years after World War II when fledgling computers, cybernetics, an immensely broadened industrial base, instantaneous communications, jet travel, and a Supreme Court decision outlawing segregated schools challenged the nation. We could have adopted policies aimed at handling millions of Appalachian coal miners and Southern cotton hands idled by the new technology. We could have planned and built new cities for the human tide about to be pushed off the land. We could have preserved our old cities, lent credit to idled men so they could found new businessess, and, in short, have made our democracy available as a participating, living reality to practically everyone. But the old biases born of our ancient regionalism reigned almost unchallenged. Multitudes of poor whites and blacks surged into Chicago, New York, and Cleveland, to name only a few of the cities that were swamped and have fallen into the chaos of today’s crime and riotousness. The well-to-do whites flee, city blocks disintegrate, and people who were too busy to think of such matters in 1955 now cower in their apartments fearful of footpads and robbers.

Advertisement

Robert Coles deals with the human consequences of these and other disregarded opportunities. He translates these consequences into contemporary, understandable human beings, millions of whom are overwhelmed by gigantic circumstances they can neither understand nor overcome. Perhaps only a psychiatrist could enable the reader to glimpse so clearly the meaning of the poverty and rootlessness that mark the lives of so many people in our society. In his books, poverty, drug addiction, welfarism, urban rioting, lawlessness, and racism cease to be abstractions. They are attached to living people and their emotions and insights become real and are shared. Suddenly one realizes what the “urban crisis” is about, above all because Coles, especially in his third volume, has followed the rural poor from the ravaged countryside to the cities they flee to; and he understands what it means to make that trip.

The United States is a land of many nations alien to one another but wholly interdependent. One of those alien nations is that of the migrant farm workers who follow the crops from state to state and whose poorly paid “stoop labor” makes possible the fresh vegetables that grace our tables. In spite of occasional outcries and congressional investigations these exploited people continue to live in unimaginable squalor, their wretchedness a disgrace to the country Lyndon Johnson delighted to call “the richest nation in the world.”

Coles visited their camps in the citrus orchards of Florida and California, the melon rows of Colorado and the Imperial Valley, the lettuce, cucumber, and pepper fields of a half-dozen states. In a decade with the migrants (and later with the mountaineers of Appalachia and the sharecroppers of the Old South) he held hundreds of conversations in fields, schools, offices of growers, homes of plantation owners, grocery stores, and gasoline stations. From it all there emerges an impression—almost a painting—of the millions who still wait on the immensity of the American land. They were shaped by it and by its history, and so shaped they move into the cities in a demographic tide he has referred to as “the South moves North.”

The migrants are at the very bottom of the economic ladder. Moving constantly from job to job, they do not register to vote. Aside from the limited achievements of Cesar Chavez, they are unorganized. Thus they are powerless in the face of the growers, who are united in their associations and maintain well-financed and potent lobbies in Washington and the state houses.

The migrants’ lives are totally without security and barely a short jump ahead of starvation. From the beginning they are boxed in by circumstances that tie them to the fields, a prey to forces neither they nor the growers can control: good crops bring glut; poor crops bring little work; rain prevents harvests; an unseasonal frost kills the plants. All hit the migrant with lessened pay for his toil. Coles writes about the children spawned in such precarious circumstances:

For nine months the infant grows and grows in the womb. The quarters are extremely limited; at the end an X-ray shows the small yet developed body quite bent over on itself and cramped; yet a whole new life has come into being. For some hundreds of thousands of American migrant children that stretch of time, those months, represent the longest rest ever to be had, the longest stay in any one place. From birth on, moves and more moves take place, quick trips and drawn-out journeys. From birth on for such children, it is travel and all that goes with travel—forced travel, by migrant farm workers who roam the American land in search of crops to harvest and enough dollars to stay alive—“to live half right.”

More often than not such children are begotten in a flimsy shack the like of which a Pennsylvania Amish farmer would never permit his cow to enter. They grow up in crowded rooms in similar shacks and hear and see other children begotten. They become pickers themselves, and at night, when most of their fellow citizens are comfortably asleep, they pass like ghosts in their dilapidated vehicles, aiming for new fields to harvest. Their new home will be like the one they just left—a shack in a row of shacks, without plumbing or toilet. A path will lead to a stinking privy. There will be no refrigeration. Diseases will be endemic. There will be no toilets in the fields, and when they relieve themselves amid the rows the excreta will spatter the food friendly neighborhood grocers will wrap in cellophane.

Advertisement

They will scarcely ever know the luxury of a few extra dollars. The office of a doctor, a dental chair, a hospital room for a woman in travail—such commonplace things are practically unknown to the dirt-poor Mexicans, blacks, and Southern whites who migrate with the crops.

The sharecroppers whom Dr. Coles visited in their cabins and plantation shacks have a shade more stability. Mississippi once had the highest per capita income in the nation—but only white men were counted and the slaves got only their “keep.” The rural South pulsed with meaning and importance as its cotton hummed through mills around the world. But that was a long time ago and the land was richer and there were no machines to plant, hoe, and harvest. Now the sharecroppers who remain—and there are still scores of thousands of them, both white and black—must farm in competition with machines that take fibre and food from the earth with the relentless precision of a watch.

Things have improved for them since the “New Frontier” was proclaimed, but they still live in awe of the sheriff and the boss-man and his “missus.” Like the cotton and corn they cultivate and the cattle they feed, they, too, are caught within an efficient machine of which they are small—and dispensable—parts. For them, as for the highlanders washed up in the Appalachian hollows, hope must lie in the world to come when Christ Jesus will come in clouds of glory and take away all sins.

The Appalachian poor had their time of importance, too, when there were many hundreds of mines and rattling tipples, and the world was warmed and powered by coal. The land was healthier then, with huge stands of virgin timber and fields where a man and his mules could bring in crops of corn and beans. But the land wore out and washed away, men turned to other fuels, and the mines fell silent. Then a new generation of bosses took over and worked the mines with machines that were cousins of the devices that drove the black men from the cotton fields. They stripped the hills and dug all the coal the world needed with a fifth as many miners.

All who could departed—though many returned—but millions were left stranded in long tiers of pauper counties that stretch across the vast sweep of Appalachia. They are white and they are destitute and they “get by” in their hollows. Their world is composed of bleak hills, crumbling coal “camps,” and decrepit shanties. They are jammed together in string towns along the roads. As Coles’s interviews make clear, they are the kept wards of the welfare state and if they have commonly accepted symbols these are the junk car and the trash heap.

These books bring into perspective a futile figure who battles against hopeless odds. He is the big city mayor whose streets and tenements, schools and hospitals are swamped by the people Coles has interviewed, and by their numberless kith and kin. They mingle with hordes of Puerto Ricans who come for the same reasons, and the “urban dilemma” suddenly stands out bold and clear. It is not urban at all, but is, as Coles shows again and again, profoundly rural in its origins and causes. It springs from a social order in which people feel a deep attachment to and affection for the soil, but have no title to it. They are pawns on a checkerboard on which the kings, too, are pathetic and helpless and doomed. The upheaval that sweeps across the nation empties the earth of people like grain pouring from a torn sack. Until the sickness of the land is healed the agony of the cities can only deepen. To seek remedies for the ghettos without stanching, somehow, the hemorrhage from the farms and towns is like treating cancer with a soothing salve.

These books should be read by every mayor and alderman, and city hall will be wise to present them as gifts to congressmen. Even though, as Mark Twain noted, congressmen are less educable than fleas, they will learn much here. They can learn, as Robert Coles did, that there are many poor helpless people scattered across our rural hinterland. They are individuals who aspire and suffer and are frustrated as individuals. Many are defeated and crushed, and surrender and passivity are stamped into their souls. Others are angry and bitter and are by no means ready to capitulate. They nurse hatreds and vengefulness, and they are going to town. It will be neither sensible nor just to blame His Excellency the Mayor for all their derelictions and misdeeds after they arrive.

Dr. Coles delineates our national malaise, which is, after all, a vast historical indigestion. His recorded voices tell us many things. They warn that in the absence of a great, finely timed opportunity we had better get down to brass tacks and make one.

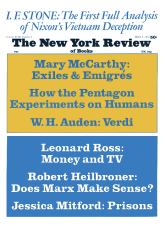

This Issue

March 9, 1972