“The whole generation-gap idea’s just an invention of the media and the Yanks. You obviously don’t know the first thing about youth in the true sense. You’ve no conception what it’s like, what it knows, what it can do.” So says Sir Roy Vandervane, nearly fifty-four, symphonic conductor, fashionable randy leftist, and the hero, in a way, of Kingsley Amis’s novel Girl, 20. Meanwhile The Tiger’s Daughter recalls that in India there are left-of-leftists:

“At least there’s still some respect for old age. My son, he has a son of his own now, but he’d never dare smoke in front of him or myself.” “Don’t worry. Soon the left-of-leftists will teach our sons disrespect.”

Bharati Mukherjee’s novel sees young India swallowing America almost as voraciously as young America swallows India: “The deliberately dirty and vituperous young man recited his anatomical verses on the lawn, then demanded some cutlets and sweetmeats for the other ‘Hungry Generation’ poets in his mess.” That tiny literary tag (“No hungry generations tread thee down”—how different the plural is) beautifully catches a complex of things: the literariness of the willed “popular” poet, the assimilation of poets to pop groups, and the deep and proper recalcitrance of true literature when one culture facilely hopes to assimilate another. Keats’s hungry generations are not hungry as India knows hunger.

There was always something dottily engaging about schooling Indians, surrounded by worklessness and fatal quietism, into reciting W. H. Davies’s “Leisure”:

What is this life, if full of care,

We have no time to stand and stare?

But when Miss Mukherjee encourages us to be amusedly perturbed by someone’s patly quoting this, it is with a chastening sense that the new missionary’s injunction—come alive, you’re in the hippie generation—is quite as inapt and inept. Her American interferer in India, Antonia Whitehead (“What India needed, she exclaimed, was less religious excitement and more birth-control devices”) is an evocation of smugness which manages—and it is very difficult—to be without smugness. In the manner, in fact, of many of the best things in Amis.

The writer who made India live in the Western consciousness, he who knew that “East is East, and West is West,” would not have thought that a liking for Indian bedspreads or even for shaven heads was evidence that what East and West are now doing is anything as simply, truly human as meeting. Tara Cartwright, née Banerjee, has graduated from Vassar and been seven years in the US: “She had burned incense sent from home (You must be careful about choosing brands when it comes to incense, her mother always said), till the hippie neighbors began to take an undue interest in her.”

The literary allusions in The Tiger’s Daughter, often dismayed at the abuses of literacy and of literature, are those of a university teacher of English (Miss Mukherjee teaches at McGill), much as the literary allusions in Girl, 20 are those of a former university teacher of English. (At one point Amis has Jonas Chuzzlewit surface with an easy lack of fearsomeness such as is weirdly charming.) All university teachers, knowing that it is part of their job to help make something of youth, don’t know what to make of youth, but it all seems to bear especially upon those who are in literature. In a recent interview in England (The Review, Summer, 1971), Robert Lowell felt honorably obliged to face both ways; on the one hand and on the other,

I don’t find all youth sympathetic—maybe ours are slightly more so because of the way they dress and slop. This generation, like ours once, is hope…. I find it disgusting when professors look to the young for vision. They should pay for sponging the youth of the young. Most students, now and always, are the Philistines, my old fraternity brothers. In our society, culture I fear must be élite; the bulk and brawn of any generation, new or past, can’t tell the Sentimental Education from Charles Reich.

Mr. Amis’s Sir Roy Vandervane can’t bear that culture should be elite, since this would lose him the affection of the disaffected young. So he composes a tawdry outdated bit of modernism, Elevations 9, which he launches in concert with a group, Pigs Out. Fortunately it sinks.

In The Tiger’s Daughter, there is a half-cracked old man, Joyonto Roy Chowdhury, who is haunted by something that surprisingly surprises him:

For almost an hour he watched and listened to the young people, having nothing to do or say himself…. He thought they were very much as he had been in his twenties, and the thought frightened him even more than he had expected.

In the end Joyonto gets caught up in a riot, is mocked, beaten, and probably about to be killed—when this precipitates a sudden instinctive act of great courage from the young man Pronob. “How dare they do that to an old man like him?” And Pronob jumps out of his car and is himself killed. It is a very disconcerting, unexpected, and hideously plausible end to the book, and it shakes into a new and telling configuration much that might have seemed merely acutely observed or delicately apprehended. For that last act of heroism is importantly instinctive, is part of a culture that can still conceive of Victorian values and Victorian words, and can believe that old age hath yet his honor and his toil. “At least there’s still some respect for old age”—and that turns out to be not just a matter of not smoking in the presence of one’s mother. Pronob’s instinctive heroism represents a laudable moral atavism such as is almost wholly lacking from the England of Amis’s novel, where the brutal beating-up of Sir Roy by some young hooligans allows even its victim not much more response than having to take it for granted.

Advertisement

Pronob’s heroism mitigates and modifies the irony with which we hear more than once those lines of Rupert Brooke, less dismissable than you might have thought. “They had taught her The Pirates of Penzance in singing class, and ‘If I should die, think only this of me’ for elocution.” And not only her, and not only as a mere matter of elocution: ” ‘If I should die,’ recited Mr. Roy Chowdhury as he came toward her, ‘think only this of me: that there’s some corner of a foreign field that is forever….’ ” India’s unique relationship to England and to English literature is delicately there, alive with the sense that if there is indeed one foreign field that is forever England—or, at any rate, that will deny and mutilate a great part of its heritage if it decides otherwise by peremptory political fiat—then it is India. Malcom Muggeridge’s remark that the only real Englishmen left are Indians was not just a joke, and it was a remark about generations as well as races.

Moreover, Rupert Brooke’s lines matter to the novel because they are a reminder that for our time the Great War is still the central and seismic fact about relations between the generations. From the bitterness of Wilfred Owen’s “Parable of the Old Man and the Young” to the awed solicitude of Philip Larkin’s “MCMXIV,” the Great War both crystallizes and smashes a relationship of old to young. Hence the talismanic quality of those lines by Brooke in Miss Mukherjee’s present-day India, as if they could ward off evil indignity. Hence, too, for all its utter difference of tone, the inescapable loathsomeness of the London pub in Girl, 20, where middle-aged mawkishness has been in collusion with youthfully emancipated jokiness to create the vulgarity of a Wipers Bar, Blighty Bar, Cookhouse, and Dug-out, complete with war posters and replicas of rifles, gas masks, and grenades. “I managed to get myself a Guinness, and went and sat down on a padded ammunition-box in a corner.” Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem for Doomed Youth” is replaced, not surprisingly, by Amis’s anathema on doomed youth.

Such a pub would have been mercifully unforeseeable, but T. S. Eliot in 1919 foresaw the dangers of that cult of youth which the decimation of youth was creating. Reviewing The New Elizabethans (“A first selection of the lives of young men who have fallen in the great war”), Eliot risked giving offense:

We are a little wearied, in fact, by the solemnity with which Mr. Osborn accepts the youthful mind and the youthful point of view. “Youth knows more about the young,” he says, “than old age or middle age.” If this were so, civilization would be impossible, experience worthless. Hommes de la trentaine, de la quarantaine, assert yourselves. Sympathy with youth is life; but acceptance of youth at its own valuation is sentiment; it is indifference to serious living.

Miss Mukherjee’s India is a country where the special difficulty that men and women in their thirties and forties may feel in asserting themselves is precisely that the older generations have for so long too rigidly asserted themselves. When a boot has been so much on one foot, it is natural for the other foot to conceive that the best and only thing is to wrest away the boot. What The Tiger’s Daughter illuminates is the analogy and interrelationship between the age-old excesses of the rich in India and those of the old (or at any rate the older); all such excesses precipitating the new excesses of revenge and indignity. “She was home in a class that lived by Victorian rules, changed decisively by the exuberance of the Hindu imagination.” The combination was always a precarious and smoldering one. And salvation will not save the situation:

Advertisement

He had acquired an official title: Deputy Chairman of the Board of Directors, Flame Co., Ltd. He spent more and more time, in custom-made raw silk shirts and cottage industries ties, managing his father’s match factory while his father, not yet sixty-two, spent more and more money purifying himself by the Ganges.

As for the Indian mother, she well sees the relation between sexual desire and insubordination. “I suspect hanky-panky business between that boy and my girl!” That this is a losing battle (though those who win will lose in their turn) is finely caught by Miss Mukherjee in the contrast between the archaic tremulousness of “hanky-panky business’ and the breathless novelty of the slang, “the words they are using right now in America,” which the girl herself swallows as an aphrodisiac.

In Amis’s England, it is the unruliness of sexual desire, coupled with the brisk feasibility of promiscuity, that so complicates the conflict between the generations. Now that the conflict is well nigh primal, there is more than one obstacle to the injunction, “Hommes de la trentaine, de la quarantaine, assert yourselves.” For the men of thirty and forty confronted by Girl, 20, there is a fatal clash between the desire to assert themselves and the desire to insert themselves. Sir Roy recalls “some other chap, in some book by a French man I seem to remember, who said he couldn’t read ‘Girl, 20’ in a small-ad column without getting the horn.” Sir Roy’s girls are “getting younger at something like half the rate he gets older”; for him the generation gap will soon be legally unpluggable.

Amis’s narrator, Douglas Yandell, is in his thirties; he wants to assert himself against the girl (seventeen, actually) who’s taking Sir Roy away from his wife (forty-six or forty-seven). But though Douglas finds it nothing but easy to detest that particular girl (some venom coursing finely here), he can’t help enjoying Sir Roy’s daughter (twenty-three). By the time Douglas comes really to like her as well as her person, she’s one of the doomed youth—this part of the book seems a submerged pun on “heroine.” Douglas manages to thwart, at least temporarily, Sir Roy’s musical foolishness, but he can’t thwart the amatory selfishness, since Sir Roy can convert any reproach into just what he needs: “He had planned to be helped to feel how deeply he was affected by the case against what he wanted to do before going off and doing it anyway.”

How can the men of thirty and forty assert themselves when they want girls, 20, and when anyway those girls have the financially powerful connivance of hommes de la cinquantaine? As always with Amis, the best things in the novel are the result of a trap and a tug. Sir Roy’s girl Sylvia is the incarnation of emancipated ruthlessness, memorably odious; but Amis doesn’t hide that there is a vituperative energy there which a vituperator can’t but admire. As in this exchange:

“What makes you such a howling bitch?”

“I expect it’s the same thing as makes you a top-heavy red-haired four-eyes who’s never had anything to come up to being tossed off by the Captain of Boats and impotent and likes bloody symphonies and fugues and the first variation comes before the statement of the theme and give me a decent glass of British beer and dash it all Carruthers I don’t know what young people are coming to these days and a scrounger and an old woman and a failure and a hanger-on and a prig and terrified and a shower and brisk rub-down every morning and you can’t throw yourself away on a little trollop like that Roy you must think of your wife Roy old boy old boy and I’ll come along but I don’t say I approve and bloody dead. Please delete the items in the above that do not apply. If any.”

This was delivered at top speed and without solicitude of any kind. Her upper lip was thinned to vanishing point and remained so while she stared silently at me. I found myself much impressed by the width of her vocabulary and social grasp.

That last irony is not a simple one, and is right to be a bit rattled.

Amis, who has always been an extraordinary mixture of imaginative fair-mindedness and last-ditch black-guardisms, doesn’t let Douglas have it all his own way. Sir Roy is making bad excuses for bad new music:

“Under late capitalism, there’s bound to be—“

“To hell with late capitalism!” I felt we had reached the important point, one that had been slopping about in the recesses of my mind for some time—reached it a good deal earlier than was opportune, but reached it we had. “All I think you’re really trying to do is arse-creep youth.”

Sir Roy laughs and has his retort: “Arse-creep. By Jove, Mr. Yandell, sir, you do show an uncommon gift for a racy phrase.” A telling retort, because that racy phrase is indeed one that would be unthinkable for anyone who had not been percolated by the very permissiveness which Douglas wants to deplore.

There are those who think that when Malcolm Muggeridge excoriates present-day England, he seems oblivious of the fact that he played some part in the making of present-day England; did not the rot set in when he became editor of Punch? Likewise there are those who think that the England of today owes a good deal of its tone, style, manners, and preoccupations to those novelists who not so long ago were Angry Young Men and who now are angry with young men. But Amis has always thrived as a writer on “It-ill-becomes-someone-who…” situations. The irony and the quandary are such as to elicit from him here much that is shrewd, fretful, and lugubriously funny, founded upon self-scrutiny and not self-regard. The ironies and the quandaries of India are something other—as yet, as yet: so Miss Mukherjee’s fine novel darkly but illuminatingly intimates.

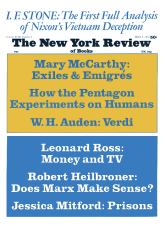

This Issue

March 9, 1972