If they keep doing versions of Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, some day they’re going to get it right. The saga of Herr Issyvoo and Sally Bowles has turned up by now in every form but roller-skating ballet, for all the world as though it were one of the sturdy myths of the West, instead of a wispy nuanced memory that has to be told right or not at all.

Granted the dawning possibility that the original has no dramatic possibilities whatever, the movie musical Cabaret may be about the best that can be done with it—certainly better than the play I Am a Camera, the movie I Am a Camera, and the stage musical Cabaret—though still many moons from the book. Each of these versions reflects the period it was produced in much more than it reflects the period Isherwood wrote about (as if the story itself were a camera), and perhaps 1972 can see itself truer in Berlin of 1930 than previous years could; or, if not, we can at least make a Berlin in our own image that has its own entertainment possibilities.

Anyway, these purveyors of mutton soup, who make their living adapting things from the forms in which they belong into forms where they taste awful, are the quintessential hacks, so it follows that the Bowles cycle is a gruesomely instructive guide to our worst show biz conventions. John van Druten’s play reads like a ghostly parody of a Forties or Fifties Broadway hit. While managing with lunatic ingenuity to pack in as many lines from the original as possible, van Druten zapped every last one with an emotional cliché of his own period. For instance, when Sally, the aspiring nymphomaniac, has her abortion, she says, “It’s like finding that all the old rules are true after all.” The original Sally would have gagged on her Prairie Oyster over that one.

Later, van Druten’s Herr Issyvoo, the camera, waxes bittersweet on the same event. “It’ll seem like another of those nasty dreams. And we won’t believe or remember a thing about it. Either of us.” (He starts to put the cigarette in his mouth. Then he stops and looks at the door.) “Or will we?” Curtain. It’s all there in the script, even the unlit cigarette, left over from Call Me at 9 and My Heart’s in the Heather.

The play emphasized Sally at the expense of Berlin. Broadway reveres a big female part and will feed anything to the flames to build a roaring one. It also likes an eccentric it can identify with completely. Thus, the year being 1951, you get amoral Sally analyzing herself like a Rose Franzblau column. “Mother never stopped nagging at me. That’s why I had to lie to her. I always lie to people, or run away from them, if they won’t accept me as I am.” The original Sally only mentioned her mother in order to lie about her and her social connections; otherwise, like Cole Porter’s Gigolo, she had no mother but jazz.

The actress being Julie Harris, Sally became a nice girl on sabbatical instead of a hopeless stray. When the play was ploughed into a film in 1955, it still featured Julie Harris and her apple pie anarchy. It dissolved, as I recall, into one of those Fifties cliffhangers about how naughty can a film get, will she say “slept with” or what? Very hard to show big bad men preparing for World War II in such a setting. Since Hollywood wasn’t even ready for Franzblau, the male part was beefed up to par (if you can call casting Laurence Harvey “beefing”). But this only took us further from Isherwood’s world, with its underlying theme of perversion and voyeurism. The original Issyvoo, the camera, may talk like an English schoolprig but he takes the most amazing pictures. He is magnetically drawn to corruption, where he nests and clicks away happily.

So far, the pale, unassertive quality of Isherwood’s book had made it an ideal “property” to be mauled into all the standard commercial shapes. Time, now, to set it to music. By the mid-Sixties, when Cabaret was spawned, the drama of private sensibility was bearish and the Broadway musical had taken to grappling with extra large themes and vast social groups which could do those great panoramic stomps and choral numbers—a day in the life of a grape-picker, or whatever. So Sally and her camera were shunted side stage to make way for German decadence and the Jewish problem. The plight of the harassed Jew, used honestly, if smotheringly, in Fiddler on the Roof earlier the same year, was slapped on rather crudely here, to demand a tear that, aesthetically speaking, belonged to some other story. One character was revealed melodramatically as a Jew, one as a Nazi. Horrors! But this wasn’t Isherwood’s point. In the book, even big-hearted, nonaligned Sally Bowles says: “I’ve been making love to a dirty old Jew producer.” That was the point.

Advertisement

Which brings us to the current movie, in which all the constituent parts—German decadence, Jew and Nazi, Issy and Sally—seem to me both more honest in themselves and better balanced with the others than in previous versions. Some of the pathologic dishonesty of Broadway and Hollywood has, of course, been sucked off by the networks; but besides that we are now so far from the original that it is possible to introduce a fresh imagination, instead of chewing down and down on Isherwood’s. If one must have adaptations, complete disregard for the originals is the safest rule.

There is one superficial problem to deal with first. Sally’s big selling point is decadence, and how does one make a movie about decadence these days? Now that we’re allowed to do it, it’s too late. Thus, when Sally and her camera make love to the same man, it seems no worse than group therapy. And when Joel Grey, the sinister nightclub MC, swings into a transvestite number, we of the Myra Breckenridge generation can only murmur, “This led to war?”

Bob Fosse, the director, and/or Jay Allen, the screenwriter, seem to understand this, so they do not try to double the decadence and reach for some last, overlooked area of shock, but concentrate instead on the gallant clumsiness of the cabaret routines, the lumbering attempts at style and at Parisian gaiety. Instead of swelling his stage to a Nazi Bund-rally grossness, Fosse shrinks it to small vulnerable frames, themselves easily blown away in the storm troopers’ dust. These also fit the off-Weill tunes of John Kander, which are meant to sound like a trombone played in a phone booth, or at least like an understaffed band trying to sound portentous, and which lost all their point in a full Broadway pit. The film suggests that these little shows did not boil up into sadistic hysteria, but were a rather touching alternative to it: as Sally Bowles’s Windermere Club was in the book.

By picture and voice overlays which are as heavy-handed as anything in Fritz Lang, Fosse makes the whole story part of the cabaret program, sharing its brief sanctuary. When the Nazis break in there, the story will be over. Meanwhile, the decadence of Sally and her friends is no worse than a nightclub turn.

The artificiality enables Fosse and Allen to slough another problem—the danger of making the Germans, whose children presumably go to movies, real enough to hate. But this could have been sloughed even better by sticking to Isherwood’s text, for once. Fosse and Allen allow Issy and Sally to be led astray by a charming German nobleman, but in the book it is a rich American drunk. In fact, all the most corrupt characters in the Berlin Stories are foreigners—an English psychopath, a Polish boy-swindler, Isherwood himself—and not Germans at all. Issyvoo wasn’t writing about German decadence (after an English public school, what else is new?) but about a shattered society where parasites of all persuasions nibble until antibodies in brown shirts begin to form.

The film handles the Jewish question itself with care. The early days of the Solution pack so much horror on their own that they will dominate any movie they’re in, even if they are played way down. Here the secret marriage of the two Jewish characters and the glimpses of street beatings are played more or less to scale with the rest. Yet each one is worth a thousand volts of Sally and her green fingernails. The film follows the book in making the principal victim (Marisa Berenson) aloof, rich, and otherwise unlike ourselves, and the street goons are presented as a bad cabaret turn, unreal as anything else. And still they knock Sally and Issy out of the box and upset Isherwood’s eerie emotional symmetry.

As for these two (Issyvoo has mysteriously become “Brian Roberts,” a fine lending-library name, but also a small sign of the film’s independence), they are obliged by filmic law to go through a form of romance with each other, but far from bestowing a Hollywood blessing, this is turned to further sinister effect: Issy is simply promoted from no sex to two. No sex was better, with its unstated note of homosexuality, but big commercial movies have not reached the stage of unstating anything.

Issyvoo’s role has been a problem in every version—what kind of conversation do you expect from a camera?—but Michael York at least conveys the manner: a Cambridge Brownie mounted on a tripos, who combines social poise with almost constant embarrassment, and who is always “on” for a good orgy yet never forgets to brush his teeth. Where the literary Isherwood switches from dumb to pompous to sophisticated to suit a scene’s focus, York sticks close to dumb. On the other hand, he looks and sounds so much like James Mason that one assumes he knows something he’s not saying.

Advertisement

As to Liza Minnelli as Sally—there is no way of liking Miss Minnelli as someone else, you must try to like her for herself. Sally’s schoolgirl precocity, her well-bred attempt to master the demimondaine manner, there is no trace of these, and nothing to replace them with either. The movie Sally also has a Franzblau past, but Liza might be lying about it. When you say your lines with that metallic brightness they could all be lies. Miss Minnelli even flunks (agreeably) the most basic of Sally’s attributes: Sally had (and it’s important) absolutely no performing talent whatever. Miss Minnelli has a little. She is a reasonably talented stage musical performer and like many better ones (Bolger, Merman) looks just plain lost on screen. Until, that is, she goes into a Judy-plays-the-Palace routine at the end, which has no connection with anything.

Of the rest, I liked Helmut Griem as Mr. Facing-both-ways, the double seducer, because he plays it without guile. He is forced to hold still for endless meaningful close-ups—confrontations in serious musicals tend to be portentously long and awkward, as if the characters were singing at each other, and real awkwardness is conveyed by a veritable dance of the elephants—but Griem retains, as a good seducer should, a sense of real unaffected friendliness.

Footnote: When I reviewed the play Cabaret, I rebuked Joel Grey, as the MC, for being too playful about his decadence. This is a reviewer’s cliché (the satire is never biting enough for us—unless it’s in bad taste) and I was wrong. Some of that German decadence probably was playful and nothing like as sinister as we thought in the days when we were so nice. Since it also gave us the German expressionist film makers and Kurt Weill and so much else, the moral question becomes whether it was done well or badly. Grey’s performance seems a little harsher this time, and he’s better in medium shot than close-up, but his instinct for the part is right, and he remains the best thing in the show.

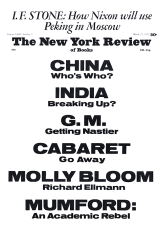

This Issue

March 23, 1972