In response to:

A Special Supplement: The Jurisprudence of Richard Nixon from the May 4, 1972 issue

To the Editors:

Ronald Dworkin’s “Nixon’s Jurisprudence” [NYR, May 4] is an uncommonly penetrating analysis. Despite its title, it has less to do with the President’s legal philosophy than with the intellectual currents in the Supreme Court and how they determine constitutional decision-making.

Dworkin is particularly effective in exposing the contradictions in the main idea underlying the theory of judicial restraint—the so-called “argument from democracy” that the electorally responsible political branches of government should in the end determine constitutional development. He shows that insofar as it applies to the Bill of Rights the idea is inconsistent with the framers’ purpose to protect individuals and minorities from the excesses of the majority, and that to remit the protections of the Constitution wholly to the political majority would be self-defeating and far from the original conception. Bear in mind, also, that Supreme Court Justices, though possessing life tenure, are usually alert to great political movements, and can be expected to trim in the popular direction out of a sense of institutional self-protection as well as responsiveness to the “felt necessities of the time.” To compound this tendency by an avowed judicial policy of “restraint” in protecting individual rights is surely to undercut the Bill of Rights mercilessly.

A passive judiciary has a further disquieting consequence. It removes the moral impetus that the Supreme Court can give to ideas that must receive their final vindication elsewhere. The rights of blacks, juveniles, women, prisoners and mental patients cannot be assured merely by judges. But the courts can help set the direction, and certainly can set a tone—as the Warren Court did—that will make it more rather than less likely that such groups will have the will and courage to assert their positions politically and successfully.

Dworkin leaves some important questions open. If one grants his (and my) conclusion that the Court has a duty to be “active,” can it avoid the pitfall of the pre-1937 Court, which was ultimately victimized by its propensity to act as a third legislative branch on all manner of social and economic issues? If the Court does manage to confine itself to the Bill of Rights, what are the criteria by which the values of equality, due process and free expression are to be given concrete content? How in particular are Supreme Court Justices to accommodate competing constitutional values, for example, when the right of free speech is pitted against the right of individual privacy? Dworkin recognizes the need for deeper debate of moral and political philosophy, ultimately the sources of legal values. With a changing Supreme Court and a changed national climate, the question is whether in some respects that debate will be too late.

Norman Dorsen

School of Law

New York University

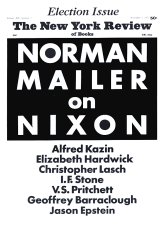

This Issue

November 2, 1972