In response to:

Thomas Eakins, Painter and Moralist from the September 21, 1972 issue

To the Editors:

I feel that I must take issue with Lewis Mumford [NYR, September 21] on one important point. Mumford states that “Eakins’s paintings piled up in his studio, unpublicized, largely unvisited.” While Eakins’s success cannot be measured in terms of sales, he was nevertheless successful in having his work seen by large numbers of people throughout the country and was certainly recognized by writers of his day as important enough to be included in numerous works on American painting.

Eakins was included in at least six of the major works on American art written prior to 1907. Hartmann devotes seven pages to a discussion of Eakins’s realism and includes a reproduction of the Gross Clinic (Sadakichi Hartmann, A History of American Art, L. C. Page & Co., Boston, 1901, Vol. I, pp. 200-207). Samuel Isham’s The History of American Painting (MacMillan, 1905 and 1927) includes numerous references to the artist and also includes a reproduction. Apparently the first reference in such a work occurs in Clara Erskine Clement and Laurence Hutton, Artists of the Nineteenth Century and Their Works (Houghton Osgood, 1879, Vol. I, p. 232). Two other early works on American painting also include reproductions of his work.

One can still find over 100 exhibition catalogues for exhibitions all over the United States in which Eakins was represented during his lifetime. He was a regular contributor to the Annual Exhibition of American Artists and the Annual Exhibition of the American Society of painters in watercolor, both held in New York City. He also participated regularly in Annuals in Boston, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati, as well as those of many other American cities. His international exposure included the exhibitions of Paris and Munich, Many special exhibitions included his work, among these, the Pan American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901, the South Carolina Interstate and West Indian Exhibition in Charlestown, South Carolina, in 1901-1902. Frequently he was represented by more than one canvas, often his work was singled out for reproduction in the catalogue. His participation in these exhibitions was often noted in the press. On three occasions he produced illustrations for the popular Scribner’s Magazine.

Measured by today’s standards that amounts to a great deal of exposure and a considerable amount of appreciation. Eakins was however largely forgotten during the years between the two major retrospective exhibitions of 1917, held after his death, and the early Twenties, which find a renewed interest in the artist as a result of exhibitions held in private galleries. These exhibitions may have been partially responsible for a series of articles dealing with firsthand reminiscences of the artist by former students and associates, Since then there has been a steady continuing interest in his work, which finds its reflection in numerous articles and exhibitions throughout the years. Among the numerous monographs, the excellent work by Goodrich holds first place.

There are unfortunately only too few of Eakins’ sketches that have survived the years. A more complete record of the artist’s approach is therefore seriously hampered by the fact that so many of these documents were destroyed. Unfortunately Eakins had no American Ruskin who could rush to the rescue and preserve them for posterity. The few nude studies that remain share the forthright and honest approach of the paintings and photographs, as well as the anatomical studies of horses. One might point out that this attention to accuracy compelled the artist to include a chaperone for the nude model in the William Rush series.

If we are to assess the role that American artists have played in the shaping of American taste and the extent to which they reflect this taste, we must dig back into the documentary evidence provided by the catalogues and periodicals of their own day. In the case of Eakins, these would tend to reveal that his personality was far from “autistic,” that he actively reached out to the American public for recognition and that he was largely accepted by his own generation. If he was forgotten it was by that generation of the late Teens and the early Twenties of our century, which looked more and more towards the European scene.

Nina Parris

University of Vermont

Burlington, Vermont

Lewis Mumford replies:

I am grateful for the additional information Nina Parris gives about the inclusion of Eakins’s work in art exhibitions during his lifetime; and doubtless Lloyd Goodrich, on whose monograph I largely relied, would have been equally pleased if this information had been at his disposal. But I fall to see in what manner this research alters the picture I have drawn of Eakins’s life and work. Does she deny that Eakins’s paintings remained stacked up in his house? Is it by accident that she does not mention a single art museum that purchased any painting of his until after his death?

But I am happy that Miss Parris’s dubious “issue” enables me to correct a singular error she made about the meaning of the next to the last sentence in my essay. Surely the context indicated that I applied the word “autistic” not to Eakins but to contemporary painters whose character and work bear no resemblance to Eakins’s. Since my essay demonstrated Eakins’s intense involvement in the life of his time, I can’t imagine by what art Miss Parris was able to twist my words around to mean their opposite.

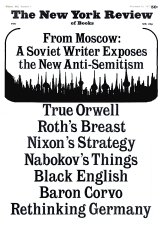

This Issue

November 16, 1972