Dorothy Wordsworth and Jane Carlyle do not present clear possibilities for comparison, but it is not out of order to think of them as products of their place in life—side by side with two of the greatest men of nineteenth-century England. The two women seem to have their being and to have their “work”—if that is the proper word for the journals and letters by which they are known—from the dramatic propinquity of William Wordsworth and Thomas Carlyle. Were they happy or unhappy? Was it enough: the letters, the gatherings at Cheyne Row, the visitors to Grasmere, the household anecdotes, and the walking tours recorded? A sort of insatiability seems to infect our feelings when we look back on women, particularly on those who are highly interesting and yet whose effort at self-definition through works is fitful, casual, that of an amateur. We are inclined to think they could have done more, that we can make retroactive demands upon them for a greater degree of independence and authenticity.

Dorothy Wordsworth is awkward and almost foolishly grand in her love and respect for and utter concentration upon her brother; she lived his life to the full. A dedication like that is an extraordinary circumstance for the one who feels it and for the one who is the object of it; it is especially touching and moving about the possibilities of human relationships when the two have large regions of equality. It is rare and we can only be relieved that Wordsworth understood and valued the intensity of it, did not take his responsibility to it lightly or try to hurt his sister so that his own vanity might be freed of all obligation. (George Lewes, one of the most lovable and brilliant men of his day, gave the same kind of love to George Eliot and to the creation and sustaining of her genius. A genuine dedication has a proper object and grows out of a deep sense of shared values. It is not usual because the arts, more than any other activity, create around them—at home, with those closest, in the world, everywhere—a sense of envy.)

We are no longer allowed such surrenders and absorptions as the Wordsworth brother and sister lived out. The possibilities for this kind of chaste, intense, ambitious, intellectual passion are completely exhausted. Wordsworth would hardly be allowed, or wish, to dream of setting up with Dorothy in a cottage, managing their frugal life, starting out with her help on his great career. Leslie Stephen has him in youth mooning about uselessly on free will, right and wrong, revolution, conscience, and “the mysteries of being.” Godwinism, with its carefree notions about family ties, was a temptation until Dorothy persuaded him of what he wished above all to be persuaded of: that he was a poet, nothing else. “It meant, in brief, that Wordsworth had by his side a woman of high enthusiasm and cognate genius, thoroughly devoted to him and capable of sharing his inspiration…. His sister led him back to nature….”

Wordsworth was not attractive in appearance. Dorothy, walking behind him, said, “Is it possible—can that be William? How very mean he looks!” No doubt she was not thinking of her own vision, but painfully imagining the skeptical, loveless eye of a stranger upon the precious person. De Quincey, discoursing upon the valuable, muchtested Wordsworth legs, says, “But useful as they proved themselves, the Wordsworthian legs were certainly not ornamental; and it was really a pity, as I agreed with a lady in thinking, that he had not another pair for evening dress parties….”

Still, dispiriting as his manner and appearance could be at times, Wordsworth had a surprising, if somewhat dour, gift with women. He established difficult, enduring relationships and kept them going with a pedestrian sort of confidence and trust. His affair in France, when he was young, with Annette Vallon was ended by prudence and a little heartlessness. His money ran out and he was propelled homeward by the firmest sense of destiny. He clearly could not, as a young man, live on in France and he could not support a wife, and he did not need a foreign one. But he kept in touch with Annette, he visited her on his tours, he met his illegitimate daughter—no hard feelings. Respect, instead.

He married a tranquil, retiring, maternal woman who had once to him been “a phantom of delight”—or so we are told. They had five children. Two died very young. A much-loved daughter died before the poet. William, his wife Mary, and Dorothy lived on and on. William was eighty when he died, Dorothy was eighty-four, Mary Wordsworth lived to be ninety. It was a thorough achievement: love, years, and poems. He never lacked the absolute devotion of women. His daughter, Dora, entered the list. There was no reason, even for the abandoned Annette, to fall entirely out of love with the nice, preoccupied genius who meant her no harm, whose pride did not need to inflict pain, plan humiliations. But what did Dorothy signify to him, what do his words really mean? And what did Carlyle actually think about his wife? Did he indeed think about her, seriously?

Advertisement

Dorothy and William Wordsworth were almost the same age. They lived all their long lives together except for a few journeys she made with a friend. They were in their twenties when they visited the Lake Country and decided to settle there. This was one of those decisions, those plot turns of destiny that we cannot question as if they were ahead of us rather than behind us. True it was forevermore narrowing, confining, and defining, but the country seemed to represent Dorothy’s undeviating inclination even more than William’s. Other possibilities had already offered themselves to his mind—the city, the university, abroad, radical groups. Dorothy’s life is overwhelmingly affected by the residence in the country: he becomes her occupation, her destiny, and what is left over goes to his family, to the hard work of living in the early 1800s.

Hiking trips, observations, the local people, Coleridge, poems read over and over each night by the fireside—this was the natural landscape of Dorothy Wordsworth’s interests and talents. Her mother had died before she was eight her father when she was twelve. She was sent to her maternal grandmother who didn’t much like her, then taken to an aunt, finally adopted by an uncle. From her earliest years her situation was close to the dreaded one we find in novels: she was a female orphan. The dearest things mysteriously vanished from her life. She had only her intelligence, her exacerbated sensibilities, and her brother.

There was always something peculiar about Dorothy Wordsworth; she is spoken of as having “wild lights in her eyes,” and is remembered as excitable and intense. There is something about her of a Brontë heroine, a romantic loneliness, a sense of having special powers of little use to the world and from which one tries to extract virtue if not self-esteem. She is said to have received several marriage offers, perhaps even from Hazlitt in one of his manic moods. It is hard to imagine any true sympathy between the austere, trembling Dorothy and the Hazlitt who complained that there were no courtesans in Wordsworth’s “Excursion.”

The enthusiasm for a quiet country life with her brother and his family perhaps cannot be wholly endorsed by contemporary women critics or by female readers given to skeptical wonderings about arrangements and destinies. Still, for Dorothy Wordsworth it was a kind of conquest; lucky, safe, and interesting. It kept her from the horror of “independence” as this condition presented itself to respectable, sensitive young women without sufficient means. The simple, earnest seclusion she had at the beginning with her brother was threatened by Wordsworth’s marriage to Dorothy’s friend, Mary Hutchinson. But again this worked and she found with them a ground of support, duty, reverence she could stand on. What alternatives were there—being a governess? Suitable marriages were almost impossible without money, beauty, or some of the scheming acquisitive nature of the lucky young women in the novels of the period. Perhaps writing could have saved her. She wrote, but it was her brother’s writing that truly became her lifelong work.

Her journals were begun early, spurred on by William. It appears that he realized the need of an “occupation” for Dorothy, an anchor for her free-flying emotions and impressions. The first notes made at Alfoxden in 1798 set the pattern for all of her writing. It is a peculiar one, trapped in the very weather of the days, concentrating upon the bare scenic surface, upon the ineffable and more or less impersonal.

Bright sunshine, went out at 3 o’clock. The sea perfectly calm blue, streaked with deeper colour by the clouds, and tongues or points of sand; on our return a gloomy red. The sun goes down. The crescent moon. Jupiter and Venus.

What rivets the attention in this early journal is not the moon or the mild morning air, but a sudden name. “Walked with Coleridge over the hills,” or “walked to Stowey with Coleridge.” Even in her youth in the lake region, nature is not a sufficient subject for the whole mind. To name it, to paint it with words is indeed a rare gift. But it is a gift almost dangling in the air. It is the final narrowness of the pictorial, the frustration of the quick microscopic brilliance, unroped by generalization.

Advertisement

In “The Grasmere Journal” a few years later, the brief, jagged portraits of country people begin, but there are also desperate hints of vulnerability. When William goes away, loneliness and panic creep in; the time is ruined by the longing for letters, the need for exhausting walks so that one could sleep. William was utterly necessary to give this isolated life meaning; without him the tranquility was a burden; alone it was nothing but waiting, filling time. Still he returned and the three months or so at Grasmere with Coleridge, while William was writing the Preface to the Lyrical Ballads, were probably the best of Dorothy Wordsworth’s life.

The journals are not so much an ambition as a sort of offering. Dorothy seems almost to be making a collection of sights, storing away moments and memories for his poetry. Much of what she wrote down is absolutely small, the merest reminder of the sun giving out its rays one moment and withdrawing them the next. She tried later in life to write some poems of her own and they are not good. She did not understand meter and wasn’t, in any case, really happy with formal constructions. Most of all she lacked generalizing power. When Wordsworth says in “Tintern Abbey” that “Nature never did betray the heart that loved her,” he was wrong in every way. For him the wanderings, the hikes, gave a sort of scenery into which he poured meaning, philosophy, morality. For Dorothy they were like moments of love, pure sensation that held the meaning of her life without clearly telling her what that meaning was.

The life of Dorothy and William Wordsworth was, as an historical act, a tremendous, demanding game, played for the highest stakes of art. Empson in Some Versions of Pastoral speaks of Wordsworth as “doing poetic field-work among country people who addressed him as Sir.” Dorothy Wordsworth sank into the heavy domestic work on the place. The children were born, there were illnesses, emergencies, as well as the steady demands. She was up at five every day. “We have also two pigs, bake all our bread at home, and though we do not wash all our clothes, yet we wash part every week and mangle or iron the whole.” On one occasion she had reason to utter the universal observation of women at home: “William, of course, never does anything.”

She undertook the work because it was right and necessary, and more necessary for her than for anyone else since in a way she was always earning the very right to share their life. But it all had an end in view. The end was the devastating, exhilarating walks and journeys—and the poems. She was creating by her walking, her feeling for nature, her enthusiasm some part of the poems, collaborating in the very private way of love or the highest kind of friendship. This is the way for gifted, energetic wives of writers to a sort of composition of their own, this peculiar illusion of collaboration. The Countess Tolstoy worried and copied and thought about his books with an energy that would have put George Sand to shame. Troyat says about her: “Her greatest source of pleasure, however, was not her husband’s embraces (she was never a passionate lover), but the manuscript he gave her to copy. And what a labor of Hercules it was, to decipher this sorcerer’s spellbook covered with lines furiously scratched out, corrections colliding with each other…. Her beautiful curling script flowed across the pages for hours.”

In Dorothy Wordsworth’s journals there is very little effort made to leave a historical record of her intense knowledge of Coleridge, Wordsworth, Southey, and others. She has little of that instinct and this is odd, especially for an author of casual, day-to-day pages. She is all decor and peripheral characters. She is making a collection of sunsets, rural joys, sustaining the pastoral mood that is her security in life. She would not dare to analyze them, to think about them in relation to herself. It was safer simply to take relationships for granted and to find conflict and character only in the changing weather and sights.

The journals were not meant for publication and her work was not printed until after her death. Sometimes she was urged to publish by friends—the poet Rogers, for instance—but when she thought of that panic set in. When she tried to be professional she revised too heavily and spoiled her effects. She speaks of having composed The Recollections of a Tour Made in Scotland—it was written down after the journey—for a few friends. But it was really, like everything else, for her brother, created in a collaborating mood.

Many of the admirers of the journals search for lines and words that turn up later in poems, as if in this way to vindicate her power, to ensure the collaborative reality. But this seeks to place her too much inside the poems, rather than rightly alongside them. And the correspondences noted by scholars are not very striking:

D. Wordsworth: When we left home the moon immensely large, the sky scattered over with clouds. These soon closed in, contracting the dimensions of the moon without concealing her.

Coleridge, “Christabel”:

The thin gray cloud is spread on high,

It covers but not hides the sky.

The moon is behind, at the full:

She sees the famous “leech-gatherer” of “Resolution and Independence.” He is sketched briefly in a few details, and nothing is made of him. He confers no philosophical lessons upon the scene. The search for correspondences is, in any case, a misunderstanding of what she was doing in the journals.

To be with her brother in nature was her role. True she was also an aunt, a helper, a vital part of a close family, but that was nothing beside the spiritual and creative companionship. William’s wife, Mary, had an even, placid, warm nature—her part in the rural scenario was set aside for maternity, wifeliness. With Dorothy, so much more vulnerable, a passive sharing would not have been sufficient. And she was not at all tranquil. Instead she was wild, driven, peculiar. Much later, when she is almost sixty, she goes mad, but she is always a little mad and in nothing more so than in her fanatic devotion to her brother.

The journals were the occupation that filled the time left over from domestic work and nature-seeing—the time after tea, before going to sleep. Her energy was overwhelming, rather hysterical and engulfing, too great. In her writing she is settling up the day, putting away the revenue in the cash register. At every moment she seems conscious of what she has to offer. She offers a sportsmanship without fatigue, an eye like a camera’s, a nice absence of skepticism. She kept him at Grasmere, working away, and it was necessary to do so since moves were a threat to her place in life—unless the moves were the journeys she excelled in.

By writing her journal she spoke of her belief in the supreme value of their lives. The mornings, the butterflies, the mists, the stops at lonely cottages, the views, the streams were magnified and glorified by the amount of work she put into them. She looked, she walked, she climbed; she returned home and with her pen looked and walked and climbed again. This double effort seems to be saying to her brother that what they have chosen is literally inexhaustible. One day might flow into another, one walk tread over the same old ground, but look how different they were, how important it was to have experienced the pale moon last night and the bright one this night.

Wordsworth writes a great poem to her, “Tintern Abbey,” and there is the deepest agitation and exhilaration of feelings as he calls out to “My dearest Friend, my dear, dear Friend,” and “My dear, dear Sister.” But we do not know what he made of her life, whether he questioned himself about it. Neither of them liked self-examination; they were private. They accepted and there was, no matter, all the business of actual life to get through; the sorrows and deaths and the writing.

The waspish De Quincey did see Dorothy Wordsworth; he looked at her very closely, he thought deeply about her. He did not accept anything as given by natural right. His memorial to her is as moving as her brother’s poems and its tone is utterly different from the sentimentality of later writers, such as E. de Selincourt. The idyllic was a part of her nature, but it was also a strenuous creation she had to sustain, a necessity, masking a spirit assaulted by uncontrollable feelings, an extravagant, dangerous temperament, a fitful education—a person above all living out a precarious dedication.

De Quincey does not hesitate to seek for the inside. He speaks of her “wild and startling eyes,” of their “hurried motions,” and he wonders what it means:

Her manner was warm and even ardent; her sensibility seemed constitutionally deep; and some subtle fire of impassioned intellect apparently burned with her, which, being alternately pushed forward into a conspicuous expression by the irrepressible instincts of her temperament, and then immediately checked, in obedience to the decorum of her sex and age, and her maidenly condition, gave to her whole demeanour, and to her conversation, an air of embarrassment, and even of self-conflict, that was most distressing to witness. Even her very utterance and enunciation often suffered in point of clearness and steadiness, from the agitation of her excessive organic sensibility. At times, the self-counteraction and self-baffling of her feelings caused her even to stammer….

We had not, from the poems or the journals, known of the stammering. Also De Quincey tells us there was something “unsexual” about her; that she did not cultivate graces. But she was deeply sympathetic and interested in everything about her. De Quincey noticed the defects of her education and he was pained to discover the gaps in her learning. He found her deeply acquainted with certain obscure authors and yet “ignorant of great classical works in her mother tongue.” He not only notices these things; he makes the effort to wonder what they mean to her. His conclusions are sad. In his eyes, the collaboration, the dependency hadn’t altogether been for the best.

I have mentioned the narrow basis on which her literary interests had been made to rest—the exclusive character of her reading, and the utter want of pretension, and of all that looks like bluestockingism, in the style of her habitual conversation and mode of dealing with literature. Now, to me it appears upon reflection, that it would have been far better had Miss Wordsworth condescended a little to the ordinary mode of pursuing literature; better for her own happiness if she had been a bluestocking; or, at least, if she had been in good earnest, a writer for the press, with the pleasant cares and solicitudes of one who has some little ventures, as it were, on that vast ocean.

So in Dorothy Wordsworth we see a rare life of the early nineteenth century, a life lived at the creative center of men like Coleridge and Wordsworth. Her fate was edged with luck in as much as she shared this life, but it was also shadowed by suffering, instability. She clung to the blessings of her condition and got with them a large measure of unfulfillments. One of the most striking things about the record she left of her life is her indifference to the character of her “dear companions.” She could not, would not analyze. There is more to think about the poets in a paragraph of De Quincey’s Reminiscences than in all of Dorothy Wordsworth. This failure to inspect character and motive incapacitates her for fiction; her lack of a rhythmical ear, her lack of training, and her withdrawal from the general, the propositional, and from questioning made it impossible for her to turn her love of nature into poetry. In her journals there are brief vignettes, good mimicry of country folk, but there are no real people—especially she and William are absent in the deepest sense.

We cannot imagine that she was incapable of thought about character, but very early, after her grief and the deaths, she must have become frightened. Her dependency was so greatly loved and so desperately clung to that she could not risk anything except the description of the scenery in which it was lived.

(This is the first part of an essay about Dorothy Wordsworth and Jane Carlyle.)

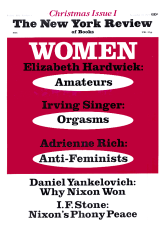

This Issue

November 30, 1972