In response to:

The Price Israel Is Paying from the August 31, 1972 issue

To the Editors:

As Israeli citizens we would like to congratulate you on the somewhat belated publication of some criticism of Israel [NYR, August 31].

In full awareness that Professor Arieli’s criticism of some Israeli policies will unleash a barrage of emotional protest from certain sections of Jewry we would like to point out some of its shortcomings.

Arieli complains that Mrs. Meir’s government “jettisons Zionist values” by allowing the employment of Palestinians from the occupied territories as manual workers in Israel. What values has he got in mind? Does he still uphold the slogans of the Zionist Left in the 1930s, namely—“Jewish labor only,” “buy Jewish only,” “redeem the land” (from whom?), etc. in order to “keep Israel Jewish”?

Does Arieli really believe it was possible to establish Jewish power in Palestine, where Jews numbered less than 20 percent of the population only forty years ago, without dispossessing and discriminating against the Palestinians?

Is the present trend of the South-Africanization of Israel an erosion of Zionist values or their logical consequence?

The chickens of Zionism have come home to roost in Mrs. Meir’s Israel (and she is not a lesser Zionist than Professor Arieli).

Isn’t the latest eruption of the Bar’am scandal ample evidence that one must proceed from a criticism of Israeli policies to a deeper critique of the whole notion of “Jewish Power”?

Oded Pilavsky, Tel Aviv

Dr. Israel Shahak, Hebrew University, Jerusalem

Akiva Orr, University College, London

Yehoshua Arieli replies:

The comments made by Messrs Pilavsky, Orr, and Shahak on my article reveal both fundamental differences of convictions and values as well as some errors of fact and misinterpretations of the text.

Let us start with the differences of views. I am a Zionist. They obviously are not. The problem which they raise is not that of “Jewish power,” whatever that may mean, but of the very existence of a Jewish state or homeland. I doubt whether such differences can be reconciled and surely this is not the place to discuss them. The real issue between us is whether the dangers indicated in my article are the inevitable consequence of the idea and practice of Zionism and the Jewish state, or whether they endanger both.

Even if the term “Jewish power” were to mean anything like “black power” it should be obvious that such a term is irrelevant to the present situation facing Jews and Arabs in Israel and the occupied territories. Jews in Israel have power by being a majority in the State. So have, to a lesser degree, the Israeli Arabs possessing the rights of citizens. It is the Palestinian Arabs of the occupied territories who have no rights and therefore no “power.” The question which I raised was whether Israel’s power should be used to rule over the Palestinian Arabs, integrating them from an economic point of view while refusing to grant them the rights of national self-determination and political independence, rights which we have claimed for ourselves as Zionists.

As a Zionist, I believe that a Jewish state cannot continue to exist for long, preserving its Jewish and democratic character, while ruling over a large national minority against its own will. Nor can this problem be solved by “imposing” the full rights of citizens and integrating the territories into the State of Israel. Such a solution has been suggested both by anti-Zionists as well as the “Greater Israel” movement led by Mr. Begin. It would lead in the end either to civil war and the erosion of the society of Israel or, what is more likely, to renewed abrogation of these rights.

The concentration of political, military, and economic power in the hands of one nation ruling over another nation has always led to colonialism on the one hand and the corruption of the rulers on the other. This process may take place slowly in nations ruling over a distant people. It would have an immediate effect in the present case where both nations live in the same territory. Zionism recognized the validity of this principle by assenting in 1937 and again in 1947-49 to the partition of the land of Eretz Israel between the two nations. The change in this situation by the Six-Day War was neither foreseen nor desired but rather imposed upon Israel by the course of events and circumstances.

The commentators claim that this was and is the inevitable and logical consequence of the Zionist concept and the existence of Israel as a Jewish state. It was my basic contention in my article that the long-term continuation of the territorial status quo undermined and contradicted the basic ethos of Zionism and endangered the very existence of Israel as a Jewish homeland and as a democracy. Only on these grounds did I consider the present economic integration of the Palestinians as a dangerous development for both sides. As I stated in my article, “A country and nation cannot be built by those who are not citizens and who do not consider themselves as belonging to the nation’s society.”

Advertisement

This has nothing to do with the situation in Palestine during the 1930s to which the writers refer. It is only natural that those who reject the concept of Zionism and the right of a Jewish homeland to exist would also attack the means by which the Jewish Labor movement under the Mandate attempted to create a Jewish economic society in Palestine. Yet, if we disregard ideology, can there be any doubt that this was the only way to create a viable Jewish society under Turkish and English Mandatory rule? Could Palestine then have absorbed a Jewish immigration of prospective laborers and farmers unless it created its own economy? Was there any chance that Jews could have been absorbed in the existing structure of the Arabic society? Would these writers have preferred Jewish society composed of landowners, capitalists, employers, merchants, and scholars?

Contrary to what these correspondents seem to think, the developing economic society created by the Zionists was not exploitative but in the literary sense creative. It created and added economic wealth in a country which up to that time had been impoverished and, in large areas, desolate. Instead of exploiting existing resources and wealth it created new economic sectors and enlarged existing ones. It is an undisputed fact that by 1947 Palestine had become one of the most developed and prosperous countries in the Middle East, benefiting in equal measure the Jewish and Arab sectors.

It is equally a fact that the “redemption of land” meant mainly the acquisition by purchase of desolate and barren stretches of soil and their transformation by the labor of the pioneers into fertile and densely populated land. Far from dispossessing Palestinian Arabs, Palestine became at that period one of the few countries in the region which attracted Arab immigrant labor from neighboring countries.

There is no resemblance whatsoever between the situation and problems of that period and the present time. Jewish society under the British Mandate was basically a voluntary self-governing society which had no coercive power. It could grow in strength only by its own creative voluntary efforts and the aid it received from world Jewry. Israel today is relatively a strong state with a short history of incredible successes. Yet its very strength and success might blind it to the temptations and dangers inherent in the uses and abuses of power, and lead it on a path directly contradicting its raison d’être and its own historic vision. The sole purpose of my article was to indicate these dangers and point out the price Israel will have to pay for disregarding them.

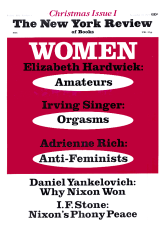

This Issue

November 30, 1972