I remember meeting General Thieu on November 5, 1963, just after the putsch in which Ngo Dinh Diem had been killed and in which Thieu had played an important if secondary part, since he commanded the division supposed to protect the northern approach to Saigon—a division on whose loyalty Diem had counted. By rallying to the conspiracy against Diem he changed the balance of forces and earned his rank as a general. But he seemed a lightweight compared to the leaders of the operation: the jovial “Big Minh,” the amiable Tran Van Don, the noisy Ton That Dinh, or the subtle Le Van Kim. At the time one hardly noticed the smooth round face of this adolescent-seeming man; and he had little to say.

But the local American experts on “strong men” kept an eye on him, not because of his talent or courage, but because this former officer in the French army was perhaps the only South Vietnamese military leader who had a clear political view. Thieu had belonged to the Dai Viet (“Greater Vietnam”), a nationalistic and violently anticommunist organization formerly supported by the Japanese. Certainly this recommended him to the American specialists in “counter-insurgency.” But when those of us who were in Saigon tried to assess the putschists grouped around Big Minh, who reminded us of General Naguib, no one would have predicted that the Nasser of the operation would turn out to be the silent Thieu with his bland regard.

For the next eighteen months Thieu remained quiet while consolidating his alliances within the army. When his friend Phan Huy Quat, another member of the Dai Viet, came to power, he was appointed Minister of Defense and vice president of the Council of Ministers. From then on Thieu gained more power and no one was able to dislodge him, neither the eccentric Nguyen Cao Ky nor the ingenious Saigon politicians. On November 5, 1967, exactly four years after our meeting, he was installed as the elected South Vietnamese chief of state. However, his power was based not so much on his legal status as on the sinuous virtuosity with which he was able to manipulate, divide, and control the army. And in South Vietnam what counts is control of the army.

If Thieu has any sincere opinion on any question it is his belief in anticommunism. “There is one way,” he said recently, “to have peace: exterminate the Communists.” Compared to him, Diem in retrospect seems a sly progressive. Did he not try to negotiate with the NLF and Hanoi? But even more perhaps than the “reds,” Thieu hates the “neutralists,” the “third force,” because such people remain a standing proof that one can be a patriot without claiming that it is necessary to exterminate one half of the Vietnamese population. And proof also that one can be noncommunist without being in the pay of the Americans.

But is Thieu merely a puppet? One must avoid oversimplification of a situation in which nothing is simple. Although he was molded, put in office, and maintained by the Americans, Thieu would not be much of a figure and would scarcely be posing problems for Henry Kissinger (who, moreover, has used and continues to make use of Thieu to raise the bidding and extract further concessions from Hanoi and the NLF) if he had not come to symbolize and incarnate certain essential realities of Vietnamese politics. So essential, in fact, that the leaders of the NLF and DRV have in large part taken account of them in their plans for peace. These realities are the political and social pluralism of South Vietnam; the profoundly capitalist nature of the southern economy; the existence of a middle class enriched by the war and hardly inclined to give up any of its wealth; the religious traditionalism of the South; and the “Sudist” sentiment itself which, having been discouraged during thirty years of war and factionalism, still weighs heavily on the minds of the South Vietnamese.

When I spoke to him on October 7, Pham Van Dong talked to me about these dissonant factors and the difficulties they pose for any adjustment or accommodation between the two parties in Vietnam. He said that both rapid unification of Vietnam and communization of the South in the near future would be “grave errors.” Where in these matters does strategy begin and ideology end?

Thieu can now fight a rear-guard action. He is already doing so by playing on the anticommunist sentiment and the fears among certain South Vietnamese groups of any signs of impending Northern domination; by shoring up the war-profiteering bourgeoisie; and by strengthening his alliances with the Catholic refugees who fled the North in 1954 and with the Buddhists opposed to progressive bonzes such as Tich Than Chau and Tri Quang.

What can Thieu hope to accomplish, apart from the satisfaction of playing a historic role and ruining for a while the arrangements for a cease-fire that his allies have been making? It would seem that a cease-fire would be more useful to the South Vietnamese army than to the NLF and their Northern allies, who generally hold the military initiative and to whom each day of combat can bring control of new territory.

Advertisement

But, in fact, the militants of the NLF find themselves extremely worried by Thieu’s attempts to delay a cease-fire. What Thieu is really planning, according to them, is the liquidation of the “third force” in South Vietnam, most of whose leaders are now in prison. They speak not only of summary executions, which recently have been said to be increasing, but of two prisons in Saigon that have been mined and could be blown up. Might Thieu, by eliminating his moderate opposition, be seeking to prove to the world that the “third force” no longer exists, and that the only forces that count are the communists’ and his own? Once again we see the tendency of right-wing regimes to insist that nothing lies between the Communist Party and themselves….

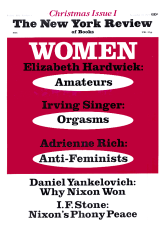

This Issue

November 30, 1972