In Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 (1966), an unlikely Jacobean tragedy is staged by a group of California players and described in the jocular manner of S. J. Perelman revisiting an old movie (“Evil Duke Angelo, meanwhile, is scheming to amalgamate the duchies of Squamuglia and Faggio, by marrying off the only royal female available, his sister Francesca, to Pasquale, the Faggian usurper…”). When the evil Duke orders the execution of the hero, “a gentle chill, an ambiguity, begins to creep in among the words” of the play.

Heretofore, the naming of names has gone on either literally or as metaphor. But now, as the Duke gives his fatal command, a new mode of expression takes over. It can only be called a kind of ritual reluctance. Certain things, it is made clear, will not be spoken aloud; certain events will not be shown on stage….

The name that is not being named here is that of the sinister, ubiquitous Tristero, a subterranean league of couriers who have been fighting monopolies of communication since the Middle Ages. Transplanted to America, they have wrought havoc with Wells Fargo, and continue to subvert and circumvent the US Postal Service. The Tristero system is used by countless Americans who have no knowledge of its meaning or history, people who have dropped out of the official network for all kinds of reasons, charmed by the stealth and the stubbornness of the counter-couriers.

The heroine of the book, having stumbled on the Tristero while trying to execute the will of an old lover, having found traces of its presence on forged stamps, in the old play, in old books, in whispered conversations, and in cryptic signs and slogans littered about the night in San Francisco, finds herself shakily facing four possibilities: the Tristero really exists, a conspiracy of communication among the excluded and the exiled; she is hallucinating it; a plot has been mounted for her benefit, possibly by her old lover, his stab at immortality, a plan for persistence in a living mind, a bequest of apparent paranoia; or she is having a fantasy about such a plot, in which case she is paranoid.

What is important about the four possibilities is that they all involve insanity, the heroine’s, her lover’s, or the world’s, and that there is no middle ground in the book between this madness and the totally insulated loneliness from which the heroine is longing to escape at the beginning, the high tower from which no prince will ever rescue her. Her choices are the tower all alone or a madness with others, a relation with others which can be mediated only by madness, and Pynchon makes it clear that these grim options confront America itself, as well as his heroine: the tower or the Tristero. The heroine, again like America, is half-trying to get back to the tower, as the Tristero, at the end of the book, clicks shut around her.

This is a characteristic moment in Pynchon’s work: things make sense, or come true, as you step reluctantly into insanity or death. A short story, “Entropy” (1960), closes with a party winding up, with a bird dying, and a man witnessing what appears to be the end of weather, a final stasis of the thermometer, the death of all motion. This is what the man has been waiting for, predicting; but it is the end of him too. The last pages of V. (1963) show us Sidney Stencil as close as he’ll ever get to knowing who V. is, what she represents (“Riot was her element,” he realizes; and notes her “obsession with bodily incorporating little bits of inert matter,” her eagerness to turn herself into death’s emblem, a living/dying testimony to the incursions of the inanimate into twentieth-century lives). But he dies then, caught up and drowned by a waterspout, like Dante’s Ulysses off the coast of Purgatory.

Pynchon’s immense new novel takes on his largest, fiercest apocalypse yet, the childhood of rocketry, V-2s from Peenemünde released by our death wish, the phallic fingers of God pointing down the sky, describing parabolas that mimic the rainbow, defeating gravity only to succumb to it and defeat us, world without end without world. They reverse nature, travel faster than sound, they strike and then you hear them. That is, if you are alive to hear them.

They must have guessed, once or twice—guessed and refused to believe—that everything, always, collectively, had been moving toward that purified shape latent in the sky, that shape of no surprise, no second chances, no return. Yet they do move forever under it, reserved for its own black-and-white bad news certainly as if it were the Rainbow, and they its children….

This is madness, of course, another paranoia, a bad joke, like the belief that the rocket’s arc is a “clear allusion to certain secret lusts that drive the planet,” or the idea that a man, the hero of this book, could have been twinned with a rocket in his childhood, sexually conditioned by electronics so that a map of his sexual adventures in London would turn out to predict the scatter of V-2s as they fell there in the autumn of 1944. Or like the idea that the dead return, or that angels appear to the dying; that you and I were meant for each other; that a man could take on the fantasies of others, dream their dreams, thereby freeing them for serious government work; that World War II was just a shuffling of markets, the killing of so many people merely a distraction, a sideshow for innocents, providing vivid material for schoolbooks; that the world is run by a cluster of large chemical companies; that the secret, real history of the world is a conspiracy of rocket-makers; that Death’s reign is at hand; that America is Europe’s colony of Death, heir to the old world’s ugliest dreams and technologies.

Advertisement

All these madnesses and more appear in Gravity’s Rainbow. As the examples indicate, some are clearly less mad than others, but all are responses to some central, nameless madness, a lurking, radiating condition of evil. Particular madnesses are splinters, fragments, metaphors, theories designed to cover up the void inhabited by the world’s real derangement, by the single encroaching discase that we can’t diagnose.

“Suppose,” Sidney Stencil thinks toward the end of V., “suppose sometime between 1859 and 1919, the world contracted a disease which no one ever took the trouble to diagnose because the symptoms were too subtle—blending in with the events of history, no different one by one but altogether—fatal.” Our chances of diagnosing the disease, if we ever had any, are gone now, and we have only the proliferating symptoms, none of which will lead us anywhere except sideways, by association, to more symptoms. From Auschwitz we can get to Hiroshima, but how do we get to the roots of either? We can’t bear this blankness, and so we invent roots, social, psychological, racial, anthropological, archaeological.

All these inventions are paranoias, Pynchon is telling us, they create connections where there are none, and he sets out, in Gravity’s Rainbow as in V., to make elaborate, sympathetic, but devastating mockery of all such enterprises. He gives us Proverbs for Paranoids: “If they can get you asking the wrong questions, they don’t have to worry about answers.” There is such a thing, it appears, as “a Puritan reflex of seeking other orders behind the visible, also known as paranoia….” A song-and-dance number:

Paranoia, Paranoia…

Even Goya couldn’t draw ya,

Not the way you looked, just kickin’ in that door.

And this novel, like The Crying of Lot 49, ends as the largest paranoia of all comes true, comforting and terminal, the falling rocket explicitly connected once again with the hand of God.

Gravity’s Rainbow is literally indescribable, a tortured cadenza of lurid imaginings and total recall that goes on longer than you can quite believe. Its people, like the characters in V., are marginal people, layabouts, dropouts, gangsters, failed scientists, despairing spiritualists, spies, SS men, dancing girls, faded movie stars. A number of old friends from V. crop up, and the names all round are a bit too doggedly whimsical for me (Roger Mexico, Tantivy Mucker-Maffick, Teddy Bloat, Major Marvy, and the like). The mythical population of the book runs from King Kong to Dillinger to Fu Manchu to Tannhäuser, with lyrics by Rilke and T. S. Eliot, and there are plenty of songs (“Quit kvetchin’, Gretchen / Go on and have a beautiful day”) and limericks and gags (as a character thinks he may be forced to marry a sow he quickly concocts a line about “unto thee I pledge my trough”).

The reconstruction of wartime London is meticulous, down to band-leaders and tunes, radio programs and the brand names of cough lozenges. I have no idea how Pynchon does this. Even if Pynchon were in London getting bombed in 1944, I can’t see how he could remember so much. And the reconstructions concern things that hardly make history books. There is clearly a mind at work here that forgets nothing and that can intuit huge canvasses from small details, whole cultures from a fragment of stone, an archaeological imagination, whose business is the impersonation of lost times: “inference,” as Pynchon has a character think in V., “poetic license, forcible dislocation of personality into a past he didn’t remember and had no right in, save the right of imaginative anxiety or historical care, which is recognised by no one.”

Advertisement

Gravity’s Rainbow, like many other modern novels, like all novels in one sense, is set in the writer’s mind, but Pynchon’s mind, by virtue of his imaginative anxiety or historical care, is full not only of personal obsessions (lavatories, sewers, shit, sadism, Germans) and personal B-movie fantasies (the windswept wastes of Kirghistan, the Argentine hero, Martin Fierro, as played by Jorge Luis Borges) but also of more major recent historical deposits than it seems a single mind could take. Webern’s historical death by mistake at the hands of the occupying American army, when it enters the book, is a perfect fictional detail, and this is how the book works, weaving all the history we are likely to remember (and then some) into a fantasy of nightmare and doom and inexplicable glee, an old movie (this metaphor for the book occurs literally dozens of times in its pages) done up and projected personally for as many as will buy or borrow the book.

It is crowded, technical, serious, self-indulgent, frivolous, and very heavy going. It doesn’t let up. From wartime London to the postwar ruins of Germany, from daffy British intelligence services to suicidal black legions of the German army, from Ick Regis (another cute name) by the English channel to the wreck of Peenemünde, we follow Pynchon’s jagged, numerous crew of extras into the Zone, as he calls it, the place in our minds which corresponds to the broken, wide-open Reich. And then we scatter, as the hero does, an American personality in pieces. Unless of course we prefer the hand of God, one last reconstructed V-2 to see us off over the rainbow, all coherence found.

I have only one hesitation about this book, about Pynchon’s whole opus. Pynchon tends to write the way the evil Duke speaks in his Jacobean play: with ritual reluctance. And then also with an overeagerness to inform, to name names. Here, as in V. and The Crying of Lot 49, things are too often either densely obscure, impossible to decipher, or excessively neat, rounded up, clicking sharply into place. We waver between lonely incomprehension and an oppressive understanding, like the heroine of Lot 49: between the tower and the Tristero. In V. there is a whole chapter (Chapter 11, “Confessions of Fausto Maijstral”) which is too lucid for the book’s good, is so clear about the book’s themes that the mystery of the rest seems something of a hoax. In this new book the phallic implications of the V-2, when they are released, seem too clumsy and too obvious to do the cosmic work they are supposed to do.

This is not too important. Pynchon’s mind is so fertile and engaging that it doesn’t matter if his books seem stilted now and again. The mind is plainly not stilted, indeed I wonder whether it could ever find a book to fit it, whether it is even, in the end, a writer’s mind at all, and not a mind of some general, undefined brilliance which has happened to find itself writing. Obviously the manner of these books corresponds closely to their matter: my difficulty in reading is the characters’ difficulty in being part of their world.

Still, there is a whole region missing in Pynchon’s fiction, the region of the suggested but not said, the shown but not expressed, the assured over-all imaginative success, as distinct from the hundreds of dazzling local successes these novels contain. Pynchon seems to feel this, since he has given us at least two marvelous comic metaphors of the communion that fails between us and him, between some of his characters and others of them, and among most of us out here, outside of fiction, perhaps, most of the time.

The heroine of The Crying of Lot 49 finds herself at a deaf-mutes’ ball—“each couple on the floor danced whatever was in the fellow’s head: tango, two-step, bossa nova, slop”—and wonders what unthinkable order of music can hold so many variables together, keep them from collisions. She is dazzled by this “mysterious consensus,” thinks of it as an anarchist miracle. “Entropy” has a jazz quartet playing without instruments, without sounds, intensely swinging through Cole Porter’s “Love for Sale.” But then, since this is a comic vision, restoring us to the world, not stranding us in paradise, the group’s next number doesn’t work so well. Different members play silently in different keys, and worse still, three of them are playing “These Foolish Things” while the other one is playing “I’ll Remember April.”

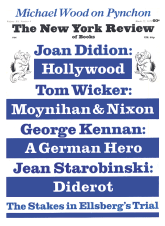

This Issue

March 22, 1973