For me and for others of my generation born in the early Thirties, the Lindbergh name sounded not heroic notes, but a dark tone. In the years preceding World War II, there were those frightening words which I did not quite understand but which were all of a piece: Lindbergh, Hauptmann, Germany, the Bund, kidnapping, the electric chair, America Firsters meeting in Yorkville. In my mind, they all came together in one malevolent force which had as its purpose the destruction of the innocents—or more specifically, me.

For our parents, who had become aware of him in his years of triumph and acclaim, I imagine there was irony in what happened to Lindbergh. This solitary stubborn man, while demanding absolute privacy in his personal life, continually catapulted himself into public view, remaining for years the popular hero of his time, only to be brought low by exactly that exalted position. The first-born son of this famous man, taken from the nursery on the isolated Lindbergh estate, Hope-well, was kidnapped and murdered.

For me, however, the Lindbergh story was a tale of demons and changelings, of goblins who stole away babies sleeping by the fireside—proof that such things did take place. Children, of course, have never felt entirely safe in their beds. Who knows exactly what is under the bed, behind the closet door? But there, outside the nursery window, had been a real murderer. Nurses and mothers worried too—for kidnapping had become a fear shared by both children and parents of my generation. Because Charles Lindbergh’s son had been spirited away, it could happen to anyone.

Even now there are people my age who have not lost their preoccupations with the Lindbergh story. Yesterday, a mimeographed letter came in the mail, the writer proclaiming that if we would only believe such evidence as could be found in the Times crossword puzzle and on the Jean Shepherd radio show, we would understand what he and the Lindberghs already knew—that he is really the lost Lindbergh son. And, oddly, the day before, I had been talking to a friend who was reading Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead, Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s letters and diaries from the early years of her marriage. We spoke of how the Lindbergh kidnapping had hung like a faint cloud over our childhood memories. “Even now,” this friend said, “I sometimes imagine myself going mad and showing up at Anne Lindbergh’s door saying, ‘It was all a mistake. I am your son.’ ”

Sufficiently horrifying in itself, the Lindbergh kidnapping became the American tragedy of the Thirties. Then as now, children have been kidnapped, some found dead, some never found. But those events are finite. Recently, for example, a baby was kidnapped from its mother, a black woman on welfare. The press treated the case briefly as a bizarre and unfortunate but transient episode. Yet, forty years after the Lindbergh kidnapping, that story remains close to the surface of mass consciousness. It stays with us because it is one of those rare events that are our equivalents of the tales of Olympus. When someone in our time rises so high as to be entirely special, our expectation, at bottom, is that he should be able to bargain with Death. When it turns out that he can make no better terms than the rest of us, he verifies again that none of us gets out of this alive—a reminder not easily forgotten.

In the tale of the Lindberghs, not only was he the air-borne frontiersman who had flown alone across the Atlantic, but his wife was the best of breed of that other prideful American strain. Anne Morrow was of that high-minded aristocracy which, being rich enough never to have to think about money, is free to concentrate on culture, good works, the cultivation of the young, and the earnestly examined life.

Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s father was ambassador to Mexico as well as a J. P. Morgan partner. Her mother was one of the rocks on which Smith College stood. In an earlier book, Bring Me a Unicorn, Mrs. Lindbergh’s view of her girlhood is overwhelmingly idyllic. The Morrows lived in a way that ordinary people might have dreamed up as fit for the deserving rich. Hers was a family whose members were forever involved in something useful and fascinating—reading great books, writing charming letters, traveling, visiting with famous and influential people, moving easily between their great summer house on the Maine coast and the splendid family home in Englewood, New Jersey, with its beautiful gardens and army of servants. The dogwood bloomed on schedule every spring without blight. In this family, no one was rude or self-indulgent or without purpose. It was the kind of family in which the young Anne Morrow could write to her grandmother:

Advertisement

Grandma, I have been so happy this spring, this summer…. Not only that, but our family. It is really so wonderful…. We are so happy in ourselves, our family…. Mother and Daddy have done it, of course. But you have done it through mother…. I am thankful for your birthday so many times. Your own self first and then you in other people…. So much of our reading and thinking—so many sweet customs…it is all you….

Only in one letter in Bring Me a Unicorn was there evidence that Anne Morrow was not entirely enchanted in her idyll. While still in high school, she wrote to her sister:

I want to go to Vassar!

Of course I have been bred and born in a Smith family…. It will take courage to break away from everything I have been brought up to love (Smith and Smith people, and the place and customs and everything) to go out and start somewhere new and against everybody’s expectations. Oh I wish to Heaven they’d let me do something strong….

But two letters later, there is word to her mother of how enormously she had enjoyed the first day of her freshman year at Smith.

Clearly, Anne Morrow did as she was told—which in such a family means to keep up the good work. She did well at Smith, read widely, won literary prizes, had the properly reverent feelings toward nature, and was respectful of literature and other people. Yet until well into the middle of Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead (when one is so shaken by the agonizing story of the kidnapping that judgment flies out the window) there had been no sense whatever that these diaries and letters had been written by anyone real. Rather, the writer had seemed a disembodied consciousness, a compilation of bits and pieces of the sensibilities of others. It is Katherine Mansfield or Emily Dickinson looking at a tree, a season, through Anne Morrow Lindbergh. It is as if Mrs. Lindbergh, in the most humanistic way possible, had been brought up with such belief in authority that it was unnatural for her to have an idea or—for that matter—a life of her own.

It was not surprising, then, that Anne Morrow was attracted to Charles Lindbergh’s brand of egocentricity and domination. People who have been too much molded by others fall easily into the obsessions of others, and Mrs. Lindbergh, turning from obedient daughter to loyal wife, made Lindbergh’s passions her own. As well as becoming a pilot, she became caught up in his mysterious machinations to avoid the publicity they attracted when they went on what can only be termed publicity junkets to call attention to what aeroplanes could do.

Clearly directed by Lindbergh, many of Mrs. Lindbergh’s letters were now written in code so that no unintentional word of their plans would leak out to the public. They went to the theater in semi-disguise and when they were recognized, Lindbergh left (although Mrs. Lindbergh notes: “As a matter of fact, people were much nicer than I imagined and though the word was passed around that we were there, they had difficulty in finding us…”).

Although Mrs. Lindbergh writes of great happiness during the first years of their marriage, one wonders at her criteria of happiness. Lindbergh kept her flying back and forth across the country even at times when she was pregnant and sick. He promised and broke repeated promises to let her visit her family in Maine—a visit she intensely longed for. A note in passing mentions that she had wanted the house at Hopewell to be built of wood—but he wanted stone, and stone it was. After the baby was born, Lindbergh, against her wishes, kept extending a trip they were making around the world—a trip which might have gone on even longer except for the death of Ambassador Morrow.

But all this has little to do with the reason for reading the book: the letters Anne Lindbergh wrote to her mother-in-law during the weeks between the time the baby was taken and the day he was found dead, as well as the diaries and letters from the following half-year. These are probably among the most painful letters ever written. I suspect there is no grief so terrible as that of a parent for a dead child. It is grief both for the child and for the person, forever indefinite, he would have become. The loss of a child is monumentally wounding to that biological instinct to protect at all costs that which is vulnerable and one’s own.

The weeks of dreadful uncertainty after the kidnapping could not have been worse. The Lindberghs tried by any and all means to get the baby back, and during that time they were at the mercy of every lunatic and scabrous hustler who had a story, a dream, or a theory about the missing child. Then it was over, and what is left finally are those pages Mrs. Lindbergh wrote with such extraordinary control which tell us, from the depths, what it was like.

Advertisement

The book closes shortly after the birth of the Lindbergh’s second son, three months after the body of their first was found. Near the end Mrs. Lindbergh writes, “It is as though having another child I now see the tragedy in the flesh. It is much more real. ‘He was as real as this on my arm…His eyes closed that way…. That happened to a child like this one.’ “

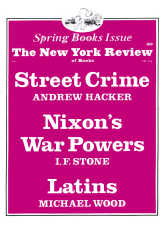

This Issue

April 19, 1973