In response to:

Poetry of the Unspeakable from the February 8, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

If I might comment on Stephen Spender’s review of Obscenities and Winning Hearts and Minds: War Poems by Vietnam Veterans [NYR, February 8], I shall be brief. As a reviewer, Mr. Spender has read more from the surface of these poems than most. The crux of his review is that this is not the work of Wilfred Owen. (It is after all the war poetry of American GIs of 1971 rather than that of British officers of 1917.) Yet instead of sensibly contrasting two irreconcilable ends of a half-century, half a world apart, Mr. Spender laments of the poets surviving Vietnam (as opposed to the survivors of Verdun) that only “one or two…is an exception in having ambitions which derive from an idea of poetry based on past examples…which exercise claims on the future.” Mr. Spender it seems is dead serious.

That, in rock n’ roll computerized America, we “brief chroniclers” of Mr. Spender’s review chose to address our (and any future) generation in poetry, demolishes that theory as thoroughly as this next aristocratic crack: “The editors’…intention is propagandistic—to influence hearts and minds regarding the war. I have of course a prejudice that poetry should survive…beyond any particular active use it may have in altering opinions. The question remains, if this is not what the poets want, should one think about their work as poetry…memorable beyond the occasion…?”

Thus spake Spender. Americans as cultural barbarians again, and I at last am sick of it. Sons as we are of mechanics and dirt farmers, mill workers, and rotarians, we still have read all of Mr. Spender’s honored ancients—as well as the less-honored Asian and American ones. That we have chosen, for the most part, our own idiom in order to try to salvage something anciently human in electronic America seems to me to be no occasion for Mr. Spender’s pomposity.

This is an argument that I thought Walt Whitman had settled. Apparently not. To borrow a phrase from Mr. Spender’s review, explaining the loss of English innocence, perhaps it is not indecent to point out that all us cruder American primitives or war poets have been corrupted and “vulgarized by the baser generalizing concerns of the society,” since birth. Born in the disaster of World War II and brought up in the disaster of mid-twentieth-century America, none of us was bred in the world of Wilfred Owen, or of Stephen Spender. (And no one else will ever again be either.) Yet we, I suspect, have read of necessity far wider of life and death and fellow men and survival than either of these two British gentlemen.

In this atomic “global village”—fast blowing itself apart back into its original atoms—we are all savages, with the Indians and the Vietnamese, having to start back over again. A place to start is the salvaging, not the continuing necromancy, of poetry.

And what we need most in America right now is not to make it “new,” or make it ancient, but to make it live. As alive as the best poetry in any language has always been. If that be “propagandistic” treason—make the most of it. It is precisely that other propaganda—anglomania, the cultured arrogance of the heirs of the British empire-English “industrial revolution,” and the pompous fawning worship of some holier-than-thou “Muse”—that has long since turned most Americans away from poetry as it is. I’d rather bring them back, than kiss the ghost of poor old Wilfred Owen.

Jan Barry

Co-editor

Winning Hearts and Minds

Brooklyn, New York

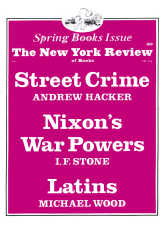

This Issue

April 19, 1973