To the Editors:

I am writing to you from France. I know that the question of granting or not granting amnesty to deserters and draft resisters of the Vietnam war deeply divides your country. You may feel that this conflict is an internal matter concerning the United States and thus does not regard Europeans. However, since this problem is a sequel of a war waged for many years against a foreign country it seems to me that any foreign country has the right to give its viewpoint. As for me, in my capacity as President of the Russell Tribunal which found the American government guilty of numerous war crimes and of genocide in Vietnam, I shall try to convey the viewpoint of the majority of Europeans.

There are very nearly a million men concerned by amnesty: war resisters, deserters, persons having left the Army with less-than-honorable discharges. This is a far cry from the “few hundred” to whom your administration has at times scornfully referred. If we add to this figure the families of these men, it is clear that we are confronted with a deep rift that the Vietnam war has created in America. These men, more or less well organized abroad, or underground in the United States, called for full amnesty (while the war was still in progress). By this they did not mean “pardon,” nor even forgetfulness. Certain of the justice of their cause, they simply wanted their rights recognized. And this could not be done unless the government was to reverse itself publicly, and, so to speak, say, “If these men have the right not to wage this war, then we on our side had no right to declare it.” Even in 1972, such an amnesty was too much to ask.

A Frenchman once said, “History never owns up to its errors.” Neither do governments, at least not completely. The government of the United States could not, without losing face, simply allow the deserters and war resisters to come home—which would not exactly be treating them as heroes, but at least as citizens of good will, who in this particular case had been right. So it was a dead-end.

Today it would seem that we have come out of this dead-end. First through the attempt at Vietnamization of the war, then in 1973 through the cease-fire, the US government, without entirely reversing itself, has implicitly recognized that it had launched an absurd war which it could not win. The war is over, and the situation is now clearer: if the US government maintains its repressive attitudes toward the deserters and draft resisters, it will prove that it has not truly understood this fact, or that its thinking is not in accordance with its actions. Consequently, no foreign country will be able to trust it. The cease-fire means: “We should never have gotten into this war”; a refusal of amnesty would mean the opposite: “we continue to find guilty those who did not want to get into it.” By granting amnesty, the government will not be in contradiction with its own logic, and will adjust to its war crimes as best it can, but it will recognize that those who judged the war criminal, contrary to international law and to the Constitution of the United States had the right not to participate. Amnesty would enhance American democracy.

For that matter, public opinion in your country is already partially prepared for such a measure. At least for the amnesty of those students, chiefly of middle-class origin, who were able to give political content to the act of burning their draft cards: 60 percent of the American population would agree to amnesty for them. It is true that the proportion is exactly the opposite—60 percent against, 20 percent in favor—when it is a question of granting amnesty to those white or black workers who joined the Army in hopes of social betterment, and who reacted to the unbearable situation they found in the Army by deserting.

There is doubtless a class reflex involved in this intolerance for deserters. And yet, these white and black men, sometimes without fully understanding themselves the significance of their conduct, made a gesture as revolutionary as that of the war resisters. An act does not lack political significance just because it is not articulately expressed in words: these men opposed an imperialist army that was bringing war to another continent. Amnesty cannot thus be limited and granted case by case. The only just amnesty must be unconditional (no alternative service) and universal. This is a political problem. The intention is obviously not to demoralize the Army, but to recognize the citizen’s right not to obey an unjust order, and further, not to participate in an imperialist war.

And we, the people of Europe, have the right to call for this amnesty as a sign that your government has no intention of someday involving us in an unjustifiable war.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Paris, France

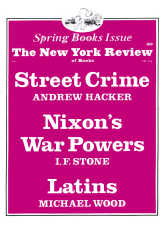

This Issue

April 19, 1973