In response to:

East Germany Lives from the March 8, 1973 issue

To the Editors:

Neal Ascherson’s review of my book, Behind The Berlin Wall [NYR, March 8], is so grotesque and insulting that I feel obliged to reply. The basic fact about the East German regime—which any attempt to explain or understand East German society must begin with—is its incredible feelings of insecurity arising from its almost total lack of popular base. During my stay in the DDR I was told time and again by young and old, workers and students, that most people would leave East Germany for the West were they not prevented from doing so by the Wall. This in turn explains, among other things, recent East German violations of the spirit, and even the letter, of the treaties on the normalization of relations. As soon as the provision allowing West Germans greater freedom to travel to relatives in the East came into effect, the East German government slapped on a new rule requiring East Germans to report the discussions they had with their Western relatives on a written form. “Visitors from the West,” reported The Economist of London (December 16, 1972), “have recently been finding that even their relations have been reluctant to see them or talk to them.” More recently, the East Germans have reneged on their agreements to release 30,000 political prisoners to West Germany, and allow a number of family reunions. After a small number of such releases, the East Germans abruptly stopped the flow—and of the prisoners released, most were common criminals (Der Spiegel, February 19, 1973). Both of these recent events can only be interpreted in the context of understanding the “opening the floodgates” fears of the East German leadership—that their support is so weak among the people that loosening up at home will lead to a dissolution of the regime’s bonds on the population.

This was a major point that I tried to emphasize in Behind The Berlin Wall, a book which consisted mostly—although one would never guess it from Ascherson’s review—of conversations with ordinary East Germans about how they reacted to their condition in a totalitarian dictatorship. For Ascherson, however, none of this is important; mocking a critic of East Germany is more important than criticizing this dictatorship.

Mr. Ascherson’s description of the circumstances surrounding my visit to East Germany is so distorted that I can only ask the interested reader to compare the actual events presented in the book with what he writes. He cannot be so disingenuous as to believe that I could have gotten a visa to stay for two months in East Germany and just roam around talking with people, nor to deny that honest journalism in Eastern Europe can be rewarded by expulsion from the country or worse.

More underhanded is Ascherson’s snide reference to my New Yorker article on East Germany being “so inaccurate that it is being circulated in East Germany as a joke.” Come now: certainly we can agree that articles from the Western press do not “circulate” in East Berlin—not among normal East Germans at any rate. I do, however, have an example of the reaction among the type of person among whom the article is circulating in East Berlin: Mr. John Peet, the British correspondent who defected to East Germany in the Fifties, and puts out an official East German propaganda publication called Democratic German Report. The November 20, 1972, issue of his publication devotes a lengthy article to exposing the many “inaccuracies” of the New Yorker article. Peet’s diatribe contains a good deal of bluster and thunder, but comes up with no important inaccuracies at all. Every point Mr. Peet deals with is trivial; and in most cases his “inaccuracies” are either not in fact inaccurate, or else matters of opinion. In my count, he came up with a total of one possible inaccuracy (I had reported pictures of party leaders on the walls of the modern apartments in the center of East Berlin; actually I saw these pictures on the walls of similar apartments in the center of Dresden, and never had time to look to see whether they were also present in East Berlin) and two points where I would reserve judgment on whether I was accurate or not (Peet denies that East German atlases devote more space to maps of the Soviet Union than to maps of Germany, and I can only speak for the one atlas I saw; Peet claims that suntan lotion is sold in East Germany, and I, basing my information on one source but never checking for myself in a store, said that it wasn’t). In any case, none of these “inaccuracies” deals with the basic theme of the book—that the totalitarian version of “socialism” practiced in Eastern Europe is not only a dreadful insult to the concept of socialism, but that it has resulted in a society of radical and unpreventable unhappiness which is a human tragedy for those who live under it and a constant warning for us in the West. Mr. Ascherson may disagree, but he should have dealt with these questions.

The New York Times (March 8) reported recently on an East German government decree regulating the activity of foreign correspondents there. The decree, writes the Times, requires correspondents “to obtain permission through its Foreign Ministry for almost all visits and interviews.” In other words, my view that it would be difficult to simply come to the DDR and go around to speak with ordinary, unselected people was correct. Furthermore, the decree goes on to “require correspondents to avoid ‘defamation’ of the East German state, its leaders, institutions, and allies on pain of being expelled.” These regulations, the Times adds, are not new, but merely represent a codification of traditional practice. One might ask in light of this why The New York Review of Books chose to give three books on East Germany to Neal Ascherson to review, when any “defamation” of East German society would lead to his losing his job as a foreign correspondent.

Steven Kelman

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Neal Ascherson replies:

The difference between Mr. Kelman and myself could be put like this: Everything in his book implies that conditions in the GDR are so frightful that any sane citizen permitted to travel West would stay there, whereas I believe that today—not ten years ago, but today—the large majority would return home. Mr. Kelman, in other words, is unwittingly backing up the GDR government’s reasons for trying to make that travel difficult, even after the Basic Treaty. It is simply not true that the population lives in aching want and under constant police terror. What maddens people is the nervous, schoolmasterly authoritarianism (not totalitarianism) of the Party, and the suffocating denial of foreign travel which Poles and Hungarians can enjoy. These are perfectly justified complaints, but they do not add up to the selective horror story written up by Mr. Kelman. Just to take a point from his letter, what makes Mr. Kelman assert that a Westerner, even a journalist, cannot get a visa to roam around East Germany talking to people? My colleagues do this frequently. Several take holidays there, actually bringing their kids with them—imagine! We seem to know different countries. Incidentally, if Mr. Kelman reads his paper properly, he will see that the new regulations apply only to resident correspondents accredited in the GDR. As before, most of the critical reporting will probably be done by visiting journalists.

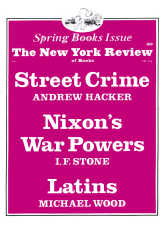

This Issue

April 19, 1973